With the Catholic Church, as with other superstitions, miracles are a way to keep simple, credulous people in awe of the supernatural and the mysterious which they need the Church and its priesthood to explain. Miraculously, they always play into the hands of the Church and its priesthood and almost always encourage the inward flow of money.

By definition, a miracle can never be proven, hence it can never be evidence for anything, for the simple fact that, to qualify as a miracle, there can be no natural explanation for the phenomenon, otherwise it's just an unusual event. The mathematician J. E. Littlewood calculated that the average person should experience a million-to-one event about once a month - in other words, the highly unusual is actually commonplace.

There can be no verifiable evidence for a miracle simply because, by definition, it wasn't natural. The only thing to go on is the word of someone else, and their unverifiable claim that they saw something which couldn't have a natural cause. As Elbert Hubbard said, "A miracle is an event described by those to whom it was told by people who did not see it."

No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact which it endeavours to establish.

David Hume

A miracle which cannot be proved is not evidence for anything.

Some claimed miracles are so patently absurd they can be dismissed as mass hallucination, Emperor's new clothes, or downright lies; claims that the sun did something strange for example.

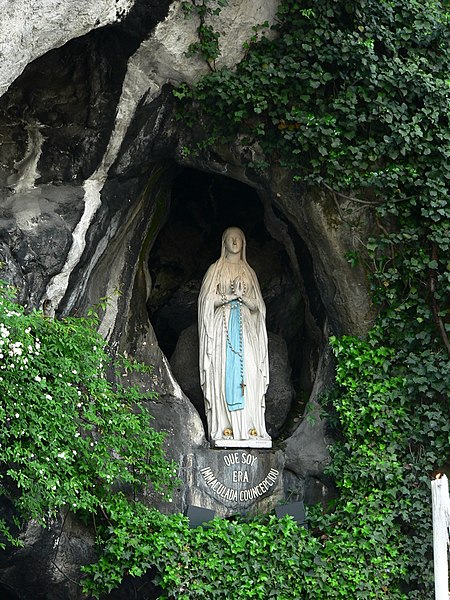

It is inconceivable that a handful of villagers, or a couple of peasant girls saw the sun zigzagging across the sky when no one else on earth saw it, and yet the Catholic Church doesn't hesitate to promote these plainly absurd 'miracles' as real events. And of course, they attract eager visitors keen to see the site of this wondrous miracle, and to buy the tacky, mass-produced, crudely made plastic souvenirs to carry the magic home in.

All the tales of miracles, with which the Old and New Testament are filled, are fit only for impostors to preach and fools to believe.

Thomas Paine

Even a simple assessment of the relative likelihoods should be enough to dismiss the miracle without further ado. Only someone ignorant of basic astronomy could be persuaded of its truth. Only someone who still believes the sun orbits Earth could believe such nonsense.

And yet the Catholic Church ships in tourists to Fatima by the coach-load to sell them magic and hocus-pocus and priest from the Pope down assure them it was all real. In 1950, Pope John XII 'remembered' seeing the miracle himself from the Vatican garden, thirty-three years earlier. He never revealed why he considered it unworthy of mention at the time.

And if you believe that, I have this bridge I'm trying to sell...

By way of illustration of how 'miracles' arise and gain traction, here is one such 'miracle' from 17th Century Spain, the so-called 'Miracle of Calanda' in which a pious young man's amputated leg allegedly suddenly re-grew overnight.

In July 1637 a 20 year-old Miguel Juan Pellicer, a devotee of the Madonna de Pilar, fell from the mule cart he was driving and a wheel ran over his lower leg, breaking his tibia. He was taken to hospital in nearby Valencia, and then he decided to walk on his broken leg to a hospital in Zaragoza dedicated to Madonna del Pilar, a journey which, because of his injury, he claimed took him fifty days. On arrival there his leg was allegedly so gangrenous that that it had to be immediately amputated below the knee. It was then buried in the hospital cemetery as was the custom.

After convalescing, he earned his living as a beggar in the vicinity of the basilica to Madonna del Pilar in Zaragoza. He later claimed that every evening he asked the servants at the basilica for a spot of oil from the lamps which he rubbed on his stump in the belief that the Madonna would restore his leg.

After a couple of years he returned home to Calanda where he continued to earn his living as a disabled beggar.

On the evening of 29 March 1640 at about ten o'clock, Miguel found his bed occupied by a soldier from a platoon temporarily billeted in Calanda so he went to sleep in a provisional bed in his parents' room, covered by a cloak. Sometime between ten thirty and eleven o'clock that same night his mother came into the room and noticed there were two feet sticking out of the bottom of the cloak. Thinking it must be another soldier she called her husband but when they removed the cloak they found Miguel deeply asleep and displaying the normal full complement of legs. When they shook him from his deep slumber he said he had been dreaming of the Madonna del Pilar and rubbing oil on his stump. They decided the restoration of the leg must have been due to the Madonna's intercession.

In those parts of the world where learning and science have prevailed, miracles have ceased; but in those parts of it as are barbarous and ignorant, miracles are still in vogue.

Ethan Allen

The place where the leg had been buried in the Zaragoza hospital cemetery was excavated and found to be empty. Quite why a divine intersession involved removing the actual original leg from its grave and restoring it, and not simply regenerating a new one was not explained. A year later, the archbishop of Zaragoza declared that an authentic miracle had occurred. Miguel was summoned to appear before King Philip IV who piously kissed the restored leg.

That's the official version with everything documented and official, some documents even still to be seen in Zaragoza Cathedral. A small industry has since grown up in Calanda to cater for the tourists who come to see, amongst other things, a sculpted image of the leg of Miguel Pillicer at the Templo del Pilar.

However:

Author Brian Dunning has done extensive research and notes that "there is no documentation or witness accounts confirming his leg was ever gone." He presents a non-miraculous explanation that Pelicer's leg did not develop gangrene during the five days at the hospital at Valencia. He spent the next 50 days convalescing, during which he was unable to work. He turned to begging, and discovered that having a broken leg was a boon. After his leg had mended, he decided that if a broken leg helped, a missing leg would be better. Travelling to Zaragoza, he bound his right foreleg up behind his thigh and for two years played the part of an amputee beggar. Later, back at his parents home in Calanda, forced to sleep in a different bed, his ruse was discovered. The story of the miracle was a way to save face. Dunning notes "that no evidence exists that his leg was ever amputated — or that he was even treated at all — at the hospital in Zaragoza other than his own word. He named three doctors there, but for some reason there is no record of their having been interviewed by either the delegation or the trial." That the hole in the cemetery of the hospital of Zaragoza in which the leg had been buried was found empty is consistent with the leg never having been amputated.So which is the more parsimonious explanation: that a beggar's ruse was rumbled, a pious tale was hurriedly cobbled together which the Catholic Church, over-eager to declare a miracle, failed to investigate properly, and that at least twenty-four people had been taken in by the ruse, or that an amputee really did have his dead and buried gangrenous (and long-ago rotted) leg miraculously resurrected from its grave in Zaragoza, teleported to a bed in Calanda, restored to life, complete with original scars and bruises, and reattached to its original owner, because he rubbed some oil from a shrine on it?

Source: Wikipedia - Miracle of Calanda

Does no one ever ask why, if restoring a dead leg to full health and reattaching it, as though nothing had ever happened to it, is so easy, why it doesn't happen more often no matter how fervently a miracle is prayed for?

Perhaps the real miracle of miracles is just how easily credulous people can be persuaded to believe them. That is almost unbelievable. Tweet

As I said, I still have that bridge for sale...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.