How Do We Make Moral Decisions?

How Do We Make Moral Decisions?Contrary to Christian apologists' assertions, humans do not get 'objective' morals from a god whose capricious whims determine right and wrong.

No matter how much C.S.Lewis tied himself into knots with his intellectual contortions, trying to prove that because he couldn't tell right from wrong, the god his mummy and daddy believed in must be real, the evidence of other cultures with other gods, and with none, shows that moral codes have broad principles common to all human cultures.

The rule probably most basic to all human cultures is the 'golden rule' - do as you would be done by or, as Christians would say, do unto others as you would have them do unto you. However, why people generally stick to this principle has been the subject of debate. Do they do it because of guilt, because we would feel bad about letting the other person down, or because of an innate sense of fairness where we want the fairest outcome.

Our study demonstrates that with moral behavior, people may not in fact always stick to the golden rule. While most people tend to exhibit some concern for others, others may demonstrate what we have called ‘moral opportunism,’ where they still want to look moral but want to maximize their own benefit.

In fact, according to the research published recently in Nature Communications, we make moral decisions according to principles that change over time and vary according to context. Some people may rely on both principles of guilt and fairness and may switch their moral rule depending on the circumstances. This finding conflicts with earlier studies which were based on the idea that people are primarily motivated by a single moral principle. Jeroen van Baar, co-lead author

Postdoctoral research associate

Department of Cognitive, Linguistic and Psychological Sciences, Brown University

Postdoctoral research associate

Department of Cognitive, Linguistic and Psychological Sciences, Brown University

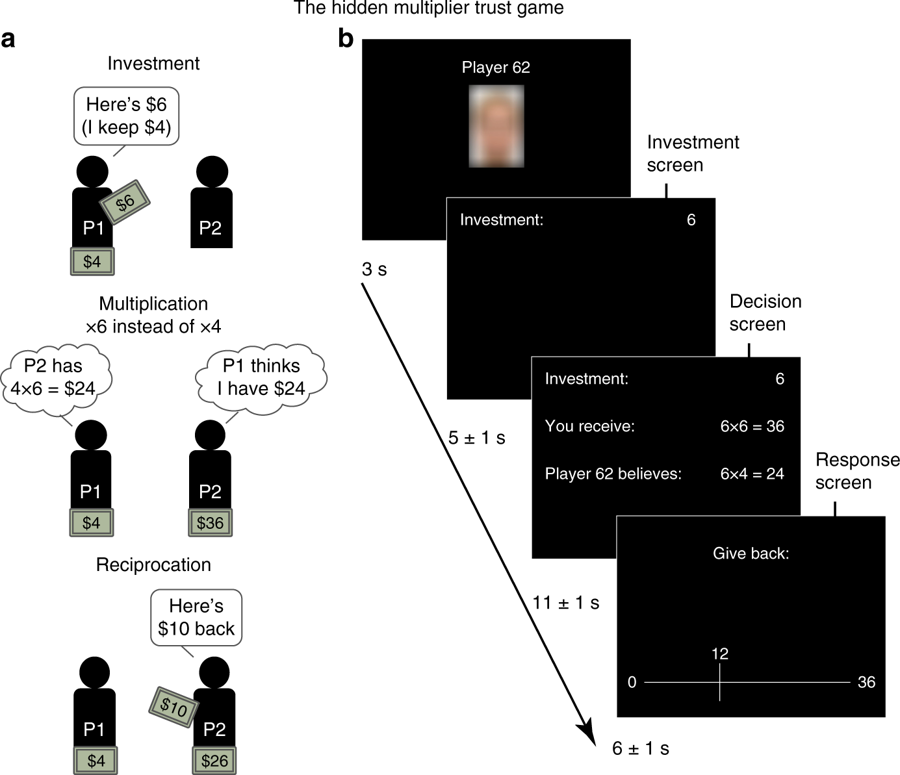

The team from Radboud University – Dartmouth College devised a modified trust game called the Hidden Multiplier Trust Game. With this method, the team could determine which type of moral strategy a study participant was using:

- Inequity aversion (where people reciprocate because they want to seek fairness in outcomes).

- Guilt aversion (where people reciprocate because they want to avoid feeling guilty).

- Greed.

- Moral opportunism (a new strategy that the team identified, where people switch between inequity aversion and guilt aversion depending on what will serve their interests best).

Abstract

Individuals employ different moral principles to guide their social decision-making, thus expressing a specific ‘moral strategy’. Which computations characterize different moral strategies, and how might they be instantiated in the brain? Here, we tackle these questions in the context of decisions about reciprocity using a modified Trust Game. We show that different participants spontaneously and consistently employ different moral strategies. By mapping an integrative computational model of reciprocity decisions onto brain activity using inter-subject representational similarity analysis of fMRI data, we find markedly different neural substrates for the strategies of ‘guilt aversion’ and ‘inequity aversion’, even under conditions where the two strategies produce the same choices. We also identify a new strategy, ‘moral opportunism’, in which participants adaptively switch between guilt and inequity aversion, with a corresponding switch observed in their neural activation patterns. These findings provide a valuable view into understanding how different individuals may utilize different moral principles.

van Baar, J. M., Chang, L. J., & Sanfey, A. G. (2019).

The computational and neural substrates of moral strategies in social decision-making.

Nature Communications, 10(1), 1483. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09161-6

Copyright: © 2019 The authors. Published by Nature Communications.

Open Access

Reprinted under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0).

In everyday life, we may not notice that our morals are context-dependent since our contexts tend to stay the same daily. However, under new circumstances, we may find that the moral rules we thought we’d always follow are actually quite malleable... This has tremendous ramifications if one considers how our moral behavior could change under new contexts, such as during war... Our results demonstrate that people may use different moral principles to make their decisions, and that some people are much more flexible and will apply different principles depending on the situation. This may explain why people that we like and respect occasionally do things that we find morally objectionable.

In addition to data generated by the Hidden Multiplier Trust Game, the team also produced brain activity patterns correlated with the moral strategies. This showed unique and distinct brain activity patterns associated with iniquity aversion and guilt aversion strategies. These brain activity patterns could be observed to switch between the strategies as the context changed.Luke J. Chang, co-author.

Assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences

Director of the Computational Social Affective Neuroscience Laboratory (Cosan Lab)

Dartmouth

Assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences

Director of the Computational Social Affective Neuroscience Laboratory (Cosan Lab)

Dartmouth

So, far from what creationists would have us believe, we not only do not have some sort of god-given objective moral principles, and nor do we need a handbook to look up right and wrong in. We have an innate psychology and a set of basic principles that we switch in and out and flip between depending on the context. This is not a product of childhood indoctrination or instructions from the pulpit, or from divining some sort of moral principles from a book which also endorses slavery, genocide and infanticide.

It is a product of neurophysiology.

There is no place for magic and no place for a capricious magic man in the sky making and handing down arbitrary moral codes which, despite being called unchanging and objective, appear to have changed drastically over time as superstition gave way to rationalism and society grew out of it's fearful and ignorant infancy, evolved and developed flexible ethics and the ability to decide which are appropriate in what context.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.