Justice Sonia Sotomayor

Blocked order forbidding Orthodox Jewish University from discriminating against LGBTQ students

Blocked order forbidding Orthodox Jewish University from discriminating against LGBTQ students

By Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, Steve Petteway Source - http://www.oyez.org/justices/sonia_sotomayor (direct link), Public Domain, Link

I wrote recently about how the American Methodists, and the Australian Anglican churches are both splitting over whether they should be continuing to victimise, demonise and generally discriminate against LGBTQ people or not. Now we have an Orthodox Jewish university in New York winning the right to discriminate on 'religious grounds'.

Yeshiva University, an Orthodox Jewish University in New York had appealed against a New York Judge’s ruling that their refusal to recognise an LGBTQ campus club violated New York City ‘s Human Rights Law, which bars discrimination based on sexual orientation, and ordered the university to recognise it as an official student club.

The University appealed to SCOTUS on the grounds that, as a religious organization, it was exempt from the non-discrimination law, by virtue of the First Amendment right to freely exercise religion. Justice Sonia Sotomayor agreed with them and issued a temporary blocking order against the NY judge's ruling. The surprise is, that Sotomayor, who hears emergency applications from the state of New York on behalf of SCOTUS, is considered to be a liberal in SCOTUS with its 6:3 majority of conservative justices, courtesy of Donald Trump who rewarded his supporters on the far right by stuffing SCOTUS with partisan religious conservative.

Now, it seems, even the liberal justices are coming into line with the highly partisan SCOTUS. There is little doubt that this ruling will be confirmed by SCOTUS with a majority of at least 7:2 and will have the effect of giving any religious organisation the right to victimise anyone with whom they disagree and the right to pick and choose which laws to comply with. The problem is, the legal definition of a 'religion' in the USA is so nebulous that such a ruling would give carte blanche to any organization or group, formal or informal, to declare itself to be a religion and ignore any law it disagrees with on the same grounds that Sotomayor ruled constitutional.

The US Dictionary of Law entry on 'Religion' reads:

ReligionIn other words, a religion can be almost anything, so long as the member(s) have 'sincerely held beliefs' (and there is no mention of how many members a religion need have to qualify as such), so, on the face of it, anyone who claims his discriminatory beliefs are sincerely held can claim the right to discriminate, in contravention of any laws prohibiting it, by virtue of his/her First Amendment freedom of religion. And there appears to be no limit to what a 'religious' person can claim constitutional protection for - paedophilia, cannibalism, slavery, animal cruelty, discrimination against disablement, gender or age … it all seems to be fair game for anyone who claims his/her beliefs are 'sincerely held'.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." The first part of this provision is known as the Establishment Clause, and the second part is known as the Free Exercise Clause. Although the First Amendment only refers to Congress, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that the Fourteenth Amendment makes the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses also binding on states (Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296, 60 S. Ct. 900, 84 L. Ed. 1213 [1940], and Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1, 67 S. Ct. 504, 91 L. Ed. 711 [1947], respectively). Since that incorporation, an extensive body of law has developed in the United States around both the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause. To determine whether an action of the federal or state government infringes upon a person's right to freedom of religion, the court must decide what qualifies as religion or religious activities for purposes of the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has interpreted religion to mean a sincere and meaningful belief that occupies in the life of its possessor a place parallel to the place held by God in the lives of other persons. The religion or religious concept need not include belief in the existence of God or a supreme being to be within the scope of the First Amendment.

As the case of United States v. Ballard, 322 U.S. 78, 64 S. Ct. 882, 88 L. Ed. 1148 (1944), demonstrates, the Supreme Court must look to the sincerity of a person's beliefs to help decide if those beliefs constitute a religion that deserves constitutional protection. The Ballard case involved the conviction of organizers of the I Am movement on grounds that they defrauded people by falsely representing that their members had supernatural powers to heal people with incurable illnesses. The Supreme Court held that the jury, in determining the line between the free exercise of religion and the punishable offense of obtaining property under False Pretenses, should not decide whether the claims of the I Am members were actually true, only whether the members honestly believed them to be true, thus qualifying the group as a religion under the Supreme Court's broad definition.

In addition, a belief does not need to be stated in traditional terms to fall within First Amendment protection. For example, Scientology—a system of beliefs that a human being is essentially a free and immortal spirit who merely inhabits a body—does not propound the existence of a supreme being, but it qualifies as a religion under the broad definition propounded by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has deliberately avoided establishing an exact or a narrow definition of religion because freedom of religion is a dynamic guarantee that was written in a manner to ensure flexibility and responsiveness to the passage of time and the development of the United States. Thus, religion is not limited to traditional denominations.

The First Amendment guarantee of freedom of religion has deeply rooted historical significance. Many of the colonists who founded the United States came to this continent to escape religious persecution and government oppression. This country's founders advocated religious freedom and sought to prevent any one religion or group of religious organizations from dominating the government or imposing its will or beliefs on society as a whole. The revolutionary philosophy encompassed the principle that the interests of society are best served if individuals are free to form their own opinions and beliefs.

When the colonies and states were first established, however, most declared a particular religion to be the religion of that region. But, by the end of the American Revolution, most state-supported churches had been disestablished, with the exceptions of the state churches of Connecticut and Massachusetts, which were disestablished in 1818 and 1833, respectively. Still, religion was undoubtedly an important element in the lives of the American colonists, and U.S. culture remains greatly influenced by religion.

Establishment Clause

The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from interfering with individual religious beliefs. The government cannot enact laws aiding any religion or establishing an official state religion. The courts have interpreted the Establishment Clause to accomplish the separation of church and state on both the national and state levels of government. The authors of the First Amendment drafted the Establishment Clause to address the problem of government sponsorship and support of religious activity. The Supreme Court has defined the meaning of the Establishment Clause in cases dealing with public financial assistance to church-related institutions, primarily parochial schools, and religious practices in the public schools. The Court has developed a three-pronged test to determine whether a statute violates the Establishment Clause. According to that test, a statute is valid as long as it has a secular purpose; its primary effect neither advances nor inhibits religion; and it is not excessively entangled with religion. Because this three-pronged test was established in Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 91 S. Ct. 2105, 29 L. Ed. 2d 745 (1971), it has come to be known as the Lemon test. Although the Supreme Court adhered to the Lemon test for several decades, since the 1990s, it has been slowly moving away from that test without having expressly rejected it. [My emphasis]

What patriotic American’s should be concerned about is that this ruling, and by one of the 'liberal' justices, is a further erosion of protection from discrimination and another enablement of the religious right to pick and choose which laws they want to comply with and who they want to abuse and victimise with impunity, and another blow against the hard-won freedoms of groups such as the LGBTQ community to live their lives free from the bullying and demonisation of others, as equal citizens in a free society.

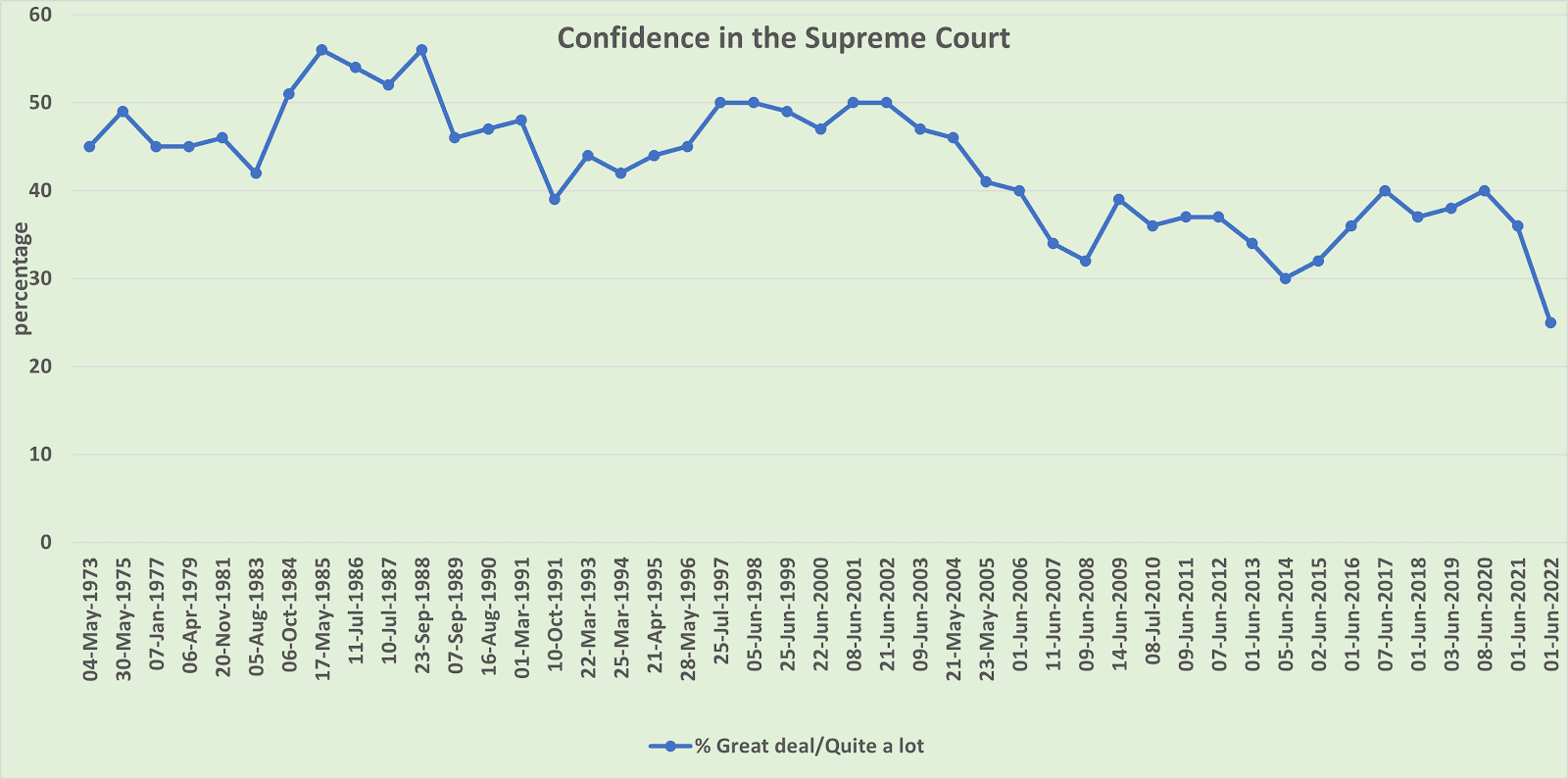

Meanwhile American confidence in SCOTUS has sunk to an all-time low, following the overturning of Roe vs Wade, in which it showed itself to be representative of only a small, bigoted minority of conservative Americans.

Another legacy of the disastrous Trump presidency.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.