NASA's James Webb Space telescope, which is performing much better than expectations, has just produced the first image of an exoplanet. The planet, HIP 65426b, is a gas giant rather like Jupiter, orbiting HIP 65426. It's presence had been inferred from data in 2017.

As a gas giant, it is not suitable for living organisms to have evolved but, with so many exoplanets being discovered, with over 5,000 discovered so far, and so many stars with potential planetary systems, it can't now be long before signs of life are detected on one or more of them.

When that happens, of course, it will destroy any remaining arguments from Creationists that the probability of a self-replicating molecule arising by chance is too small to be credible as an explanation for how life got going on Earth. It will show that, if the conditions are right, chemistry and physics alone are quite capable of producing that and the probability of a planet with those conditions being discovered, increases with every new exoplanet discovered.

The chances of finding such a planet are greater the closer the planetary system is to Earth for the simple reason that telescopes such as the James Webb, see distant objects as they were when the light left them, so a planet say, 10 billion lightyears away, will appear as it was 10 billion years ago. We know it took the Universe 10-11 billion years to give rise to Earth before life could get going some 500 million years later, so distant object may not have had time when we are seeing them, to have reached that stage. Closer objects will have had more time.

The image from the James Webb Space Telescope, and its significance is explained in an open access article in The Conversation by Professor Jonti Horner, Professor (Astrophysics), University of Southern Queensland, Australia. The article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original article can be read here.

The Webb telescope has released its very first exoplanet image – here’s what we can learn from it

Jonti Horner, University of Southern Queensland

Did you ever want to see an alien world? A planet orbiting a distant star, light years from the Sun? Well, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has just returned its first-ever picture of just that – a planet orbiting a distant star.

The new images reveal JWST will be a fantastic tool for astronomers aiming to improve their knowledge of exoplanets (planets around other stars) – even better than we had hoped it would be!

But for those who’ve grown up on a diet of Star Trek, Star Wars, and myriad other works of science fiction, the images may be underwhelming. No wonderful swirling clouds, in glorious or muted colours. Instead, we just see a blob – a single point of light.

So why do these observations have astronomers buzzing with excitement? And what might we learn in the months and years to come?

Observing hidden worlds

Over the past three decades, we have lived through a great revolution – the dawn of the Exoplanet Era. Where we once knew of no planets orbiting distant stars, and wondered whether the Solar System was unique, we now know planets are everywhere.

The history of the first 5,000 alien worlds discovered – the dawn of the Exoplanet Era.

But the overwhelming majority of those exoplanets are detected indirectly. They orbit so close to their host stars that, with current technology, we simply cannot see them directly. Instead, we observe their host stars doing something unexpected, and infer from that the presence of their unseen planetary companions.

Of all those alien worlds, only a handful have been seen directly. The poster child for such systems is HR 8799, whose four giant planets have been imaged so frequently that astronomers have produced a movie showing them moving in their orbits around their host star.

The first video of exoplanets orbiting their star. HR 8799 host four super-Jupiters, and it took seven years of imaging data to produce this movie.

Enter HIP 65426b

To gather JWST’s first direct images of an exoplanet, astronomers turned the telescope towards the star HIP 65426, whose massive planetary companion HIP 65426b was discovered using direct imaging back in 2017.

HIP 65426b is unusual in several ways – all of which act to make it a particularly “easy” target for direct imaging. First, it is a long way from its host star, orbiting roughly 92 times farther from HIP 65426 than the distance between Earth and the Sun. That puts it around 14 billion kilometres from its star. From our point of view, this makes for a “reasonable” distance from the star in the sky, making it easier to observe.

Next, HIP 65426b is a behemoth of a world – thought to be several times the mass of the Solar System’s biggest planet, Jupiter. On top of that, it was also previously found to be remarkably hot, with temperature at its cloud tops measuring at least 1,200℃.

This combination of the planet’s size and temperature means it is intrinsically bright (for a planet).

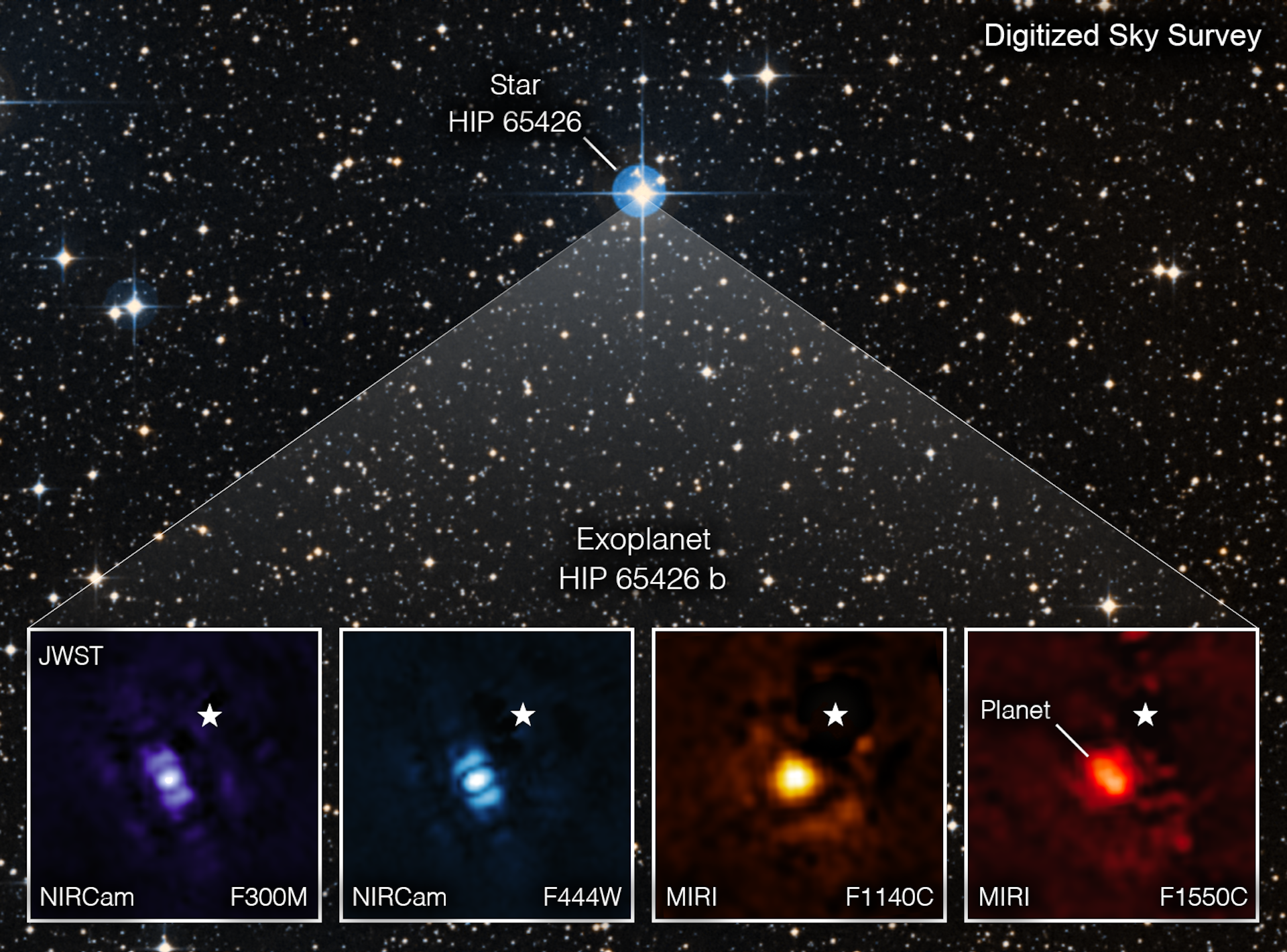

JWST’s first images of an alien world, HIP 65426b, are shown at the bottom of a wider image showing the planet’s host star. The images were taken at different wavelengths of infrared light.

NASA/ESA/CSA, A Carter (UCSC), the ERS 1386 team, and A. Pagan (STScI).

Read more:

Will NASA rename the James Webb Space Telescope? A space expert explains the Lavender Scare controversy

How were the images taken, and what do they show us?

Under normal circumstances, the light from HIP 65426 would utterly overwhelm that from HIP 65426b, despite the distance between them.

To get around this problem, JWST carries several “coronagraphs”, instruments that let the telescope block the light from a bright star to look for fainter objects beside it. This is a bit like blocking the headlights of a car with your hand to see whether your friend has climbed out to say hello.

Using these coronagraphs, JWST took a series of images of HIP 65426b, each taken at a different wavelength of infrared light. In each image, the planet can be clearly seen – a single bright pixel offset from the location of its obscured stellar host.

The images are far from your standard science fiction fare. But they show that the planet was easily detected, standing out like a sore thumb against the dark background of space.

The researchers who led the observations (detailed on the preprint server arXiv) found that JWST is performing around ten times better than expected – a result that has astronomers around the globe excited to see what comes next.

Using their observations, they determined the mass of HIP 65426b (roughly seven times that of Jupiter). Beyond that, the data reveal the planet is hotter than previously thought (with cloud tops close to 1,400℃), and somewhat smaller than expected (with a diameter about 92% that of Jupiter).

These images paint a picture of an utterly alien world, different to anything in the Solar System.

Read more:

James Webb Space Telescope: An astronomer explains the stunning, newly released first images

A signpost to the future

The observations of HIP 65426b are just the first sign of what JWST can do in imaging planets around other stars.

The incredible precision of the imaging data suggests JWST will be able to obtain direct observations of planets smaller than previously expected. Rather than being limited to planets more massive than Jupiter, it should be able to see planets comparable to, or even smaller than, Saturn.

This is a really exciting. You see, a basic rule of astronomy is that there are lots more small things than big things. The fact JWST should be able to see smaller and fainter planets than expected will greatly increase the number of possible targets available for astronomers to study.

Beyond that, the precision with which JWST carried out these measurements suggests we will be able to learn far more about their atmospheres than expected. Repeated observations with the telescope could even reveal details of how those atmospheres vary with time.

In the coming years, then, expect to see many more images of alien worlds, taken by JWST. While those pictures might not look like those in science fiction, they will still revolutionise our understanding of planets around other stars.

Read more:

To search for alien life, astronomers will look for clues in the atmospheres of distant planets – and the James Webb Space Telescope just proved it's possible to do so

Jonti Horner, Professor (Astrophysics), University of Southern Queensland

And no doubt theologians will debate endlessly about whether Jesus needed to be born and sacrificed on all those other planets with life on them in order to save the inhabitants from the consequences of their founding couple's sin, or whether life on them is some sort of idyll ,the way it would have been here had the serpent not tempted Eve. One way or another the new information will need to be shoe-horned into the Bible narrative because the priest and theologians livelihood depends on it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.