Old World flycatchers’ family tree mapped - Uppsala University, Sweden

In yet another casual refutation of the plaintive Creationist assertion that the Theory of Evolution (TOE) is about to be overthrown by their childish Bronze Age superstition, scientists from Uppsala and Gothenburg Universities, Sweden and Florida University, USA, have produced a family tree of the Old World flycatchers - a family of birds that includes the European Robin.

In doing so, they found not the slightest hint that the TOE is inadequate to explain the observations. In fact, as expected, it is entirely consistent with what they found.

As the article in Uppsala University news by Elin Bäckström explains:

Religion, Creationism, evolution, science and politics from a centre-left atheist humanist. The blog religious frauds tell lies about.

Pages

▼

Wednesday, 30 November 2022

Monday, 28 November 2022

Creationism in Crisis - Scientists Debate How Evolution Works, Not Whether it Happens

The study of evolution is fracturing – and that may be a good thing

Creationists who have been fooled into believing that the Theory of Evolution (TOE) is being increasingly rejected by mainstream scientists will undoubtedly take some comfort from the fact that there is an ongoing, and increasing debate amongst serious biologists about the theory.

Sadly for Creationists, however, the debate isn't about whether species evolved and are evolving or whether they were made by magic; it's about how exactly evolution happens.

Debate, is of course, healthy and essential within science. It is the Darwinian environment in which scientific ideas evolve and improve, because, science, unlike religion, is based on the idea that when the facts change, opinions should change to accommodate the new information.

In other words, the debate is about the detail, not the fact. No serious biologist is in any doubt about the fact of evolutionary change being the cause of speciation, and why species changes over time and vary between populations under the influence of environmental selectors, just as Darwin and Wallace outlined in 1859.

In the following article, reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, Professor Erik Svensson of Lund University, Sweden, explains the background to the debate, why debate is healthy and how it poses no threat to the basic idea of evolutions. The article has been reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Creationists who have been fooled into believing that the Theory of Evolution (TOE) is being increasingly rejected by mainstream scientists will undoubtedly take some comfort from the fact that there is an ongoing, and increasing debate amongst serious biologists about the theory.

Sadly for Creationists, however, the debate isn't about whether species evolved and are evolving or whether they were made by magic; it's about how exactly evolution happens.

Debate, is of course, healthy and essential within science. It is the Darwinian environment in which scientific ideas evolve and improve, because, science, unlike religion, is based on the idea that when the facts change, opinions should change to accommodate the new information.

In other words, the debate is about the detail, not the fact. No serious biologist is in any doubt about the fact of evolutionary change being the cause of speciation, and why species changes over time and vary between populations under the influence of environmental selectors, just as Darwin and Wallace outlined in 1859.

In the following article, reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, Professor Erik Svensson of Lund University, Sweden, explains the background to the debate, why debate is healthy and how it poses no threat to the basic idea of evolutions. The article has been reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Sunday, 27 November 2022

Unintelligent Designer News - Podcast Now Available

Well, the live show went okay, despite a slight technical hitch with getting the presentation video to run, which gave more time for debate but, sadly, less time for the video. So here it is for anyone who wants to see the entire thing.

Also, the entire show can be viewed again here: As I said, my book, "The Malevolent Designer: Exposing the Intelligent Design Hoax", contains many more examples of the things in nature that show there was no intelligence or design in what we can observe.

An illustrated companion book, "The Malevolent Designer: Why Nature's God is not Good", is also available in hardcover, paperback or ebook for Kindle, as are my other books on science and religion.

Also, the entire show can be viewed again here: As I said, my book, "The Malevolent Designer: Exposing the Intelligent Design Hoax", contains many more examples of the things in nature that show there was no intelligence or design in what we can observe.

An illustrated companion book, "The Malevolent Designer: Why Nature's God is not Good", is also available in hardcover, paperback or ebook for Kindle, as are my other books on science and religion.

Creationism in Crisis - How the Arthropod Brain Evolved 525 million Years Ago

525-million-year-old fossil defies textbook explanation for brain evolution | University of Arizona News

A paper published a couple of days ago in Science closes yet another of those gaps so beloved of Creationists who fool their dupes with the false dichotomy fallacy that, if science hasn't explained something, the only alternative on offer is that their version of a creator god did it. This save them the bother of producing any evidence for their pet superstition and keeps their dupes believing that they have better answers than science does and so are much more clever than those elitist scientists with their big words. If there is one thing Creationists can't stand it's uncertainty, with the dreadful prospect that they might have to change their minds if the evidence changes.

The paper was written by a group of scientists led by Nicholas Strausfeld, a Regents Professor in the University of Arizona Department of Neuroscience, and Frank Hirth, a reader of evolutionary neuroscience at King's College London. It describes a fossil of Cardiodictyon catenulum, a 1.5 cm long, worm-like arthropod, found in China's southern Yunnan province. Close detailed analysis has revealed delicately preserved nervous system, including a brain. This is believed to be the oldest fossilised brain so far discovered.

The University of Arizona News describes the research and its significance:

A paper published a couple of days ago in Science closes yet another of those gaps so beloved of Creationists who fool their dupes with the false dichotomy fallacy that, if science hasn't explained something, the only alternative on offer is that their version of a creator god did it. This save them the bother of producing any evidence for their pet superstition and keeps their dupes believing that they have better answers than science does and so are much more clever than those elitist scientists with their big words. If there is one thing Creationists can't stand it's uncertainty, with the dreadful prospect that they might have to change their minds if the evidence changes.

The paper was written by a group of scientists led by Nicholas Strausfeld, a Regents Professor in the University of Arizona Department of Neuroscience, and Frank Hirth, a reader of evolutionary neuroscience at King's College London. It describes a fossil of Cardiodictyon catenulum, a 1.5 cm long, worm-like arthropod, found in China's southern Yunnan province. Close detailed analysis has revealed delicately preserved nervous system, including a brain. This is believed to be the oldest fossilised brain so far discovered.

The University of Arizona News describes the research and its significance:

Saturday, 26 November 2022

Creationism in Crisis - Fossils from Gondwana Show Evolution and Ecosystems 266 Million Years Ago

Exquisite new fossils from South Africa offer a glimpse into a thriving ecosystem 266 million years ago

Creationist frauds who want to convince their cult members that the Theory of Evolution is about to be replaced in mainstream science by their childish superstition, and so become the first scientific theory ever to be replaced with an evidence-free superstition involving imaginary supernatural entities, have to keep them ignorant of papers such as this one which has just been published in Communications Biology.

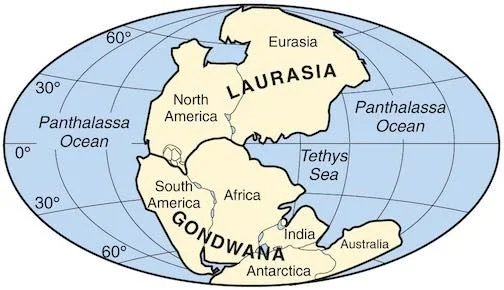

The paper, by a team of scientists led by Rosemary Prevec, a palaeontologist with Rhodes University Department of Botany, and the Department of Earth Science, Albany Museum, Makhanda, South Africa, reports on an exceptionally well preserved collection of fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids and plants - what is known to science as a 'Lagerstätte'. What's more, the formation has 'robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context', in other words, the fossils can be accurately placed in time and the changing geography of the time - some 266–268 million years ago in a river delta, when Earth had just two major landmass known as Gondwana and Laurasia, the northern and southern parts of Pangea respectively, before they were broken up and in some cases forced together by tectonic forces to form today’s major continents.

These fossils enabled the team to reconstruct the ecosystem of the time. An ecosystem is the result of interactions between species of animals and plants in a given area - the fundamental conditions for evolution to occur, as the ecosystem changes in response to internal and external pressures.

The team leader, Rosemary Prevec, has written the following article in The Conversation to explain the background to the discovery and its significance in terms of understanding the evolution of some species and the extinction of others. The Theory of Evolution is, of course, fundamental to research such as this in order to make sense of the observations. Note that nowhere does the author show the slightest doubt about the TOE's value in that understanding.

Her article is reproduced under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Rosemary Prevec, Rhodes University

South Africa is famous for its amazingly rich and diverse fossil record. The country’s rocks document more than 3.5 billion years of life on Earth: ancient forms of bacterial life, the emergence of life onto land, the evolution of seed-producing plants, reptiles, dinosaurs and mammals – and humanity.

Many will be familiar with hominid fossils such as the Australopithecus africanus skull Mrs (or is it Mr?) Ples and the paradigm-shifting Taung child. Less well known and equally important fossils such as the oldest terrestrial vertebrates in the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which document the first steps from the ocean and onto land, have also emerged from South Africa. The country’s wealth of fossils is due in part to the region’s unique geology, which documents 100 million years of nearly continuous deposition in its Karoo Basin.

Fossils also hold clues to climatic shifts, from the great Carboniferous ice age over 300 million years ago, to the huge dunes of blazing Jurassic deserts where dinosaurs roamed 200 million years ago. Scientists can read the devastation of the mass extinction events that destroyed global ecosystems and changed the course of Earth’s history.

But in the race to understand the “big picture” of the evolution of life and to distil its dramatic ups and downs into punchy headlines, it is easy to forget the small and quiet things. Pause, and consider what life looked like on an average day, in a world without humans, mammals, birds, butterflies, flowers, or even dinosaurs. What was it like on the shores of a rippling lake, on a drowsy summer afternoon, 266 million years ago in what’s now the Northern Cape province of South Africa?

The search, and what we found

In a new paper, my colleagues and I provide the first glimpse of such an ecosystem. We have found a profusion of fossils of tiny insects that have never been found before, as well as important plant specimens that are changing our understanding of how they evolved.

Our findings give fresh insights into the effects of extinction events on ecosystems. The subject has taken on great urgency in the face of what scientists are calling the sixth great extinction event, which is being driven by the current trend of global warming.

For the past few years we have been excavating a small, nondescript rock outcrop near Sutherland in the Northern Cape.

This outcrop is yielding untold fossil treasures of plants, insects and other invertebrates that are new to science. These unique fossils, some only a few millimetres long, are telling us about what lived in and around a calm pool on a delta plain during the middle Permian period between 266 million and 268 million years ago. Rocks of this age contain fossils of the oldest therapsids, a group of reptiles that eventually gave rise to the mammals.

Other life of this time included the lizard-like ancestors of tortoises, large amphibians that lurked like crocodiles just below the water surface, and forests dominated by a tree called Glossopteris with an understorey of spore-producing plants such as mosses, ferns and horsetails.

Teams of palaeontologists have discovered and excavated many hundreds of vertebrate fossils in the western and southern Karoo of South Africa that date back to the Permian, including the Sutherland District and surrounding areas. But the kinds of rocks that are rich in vertebrate fossil bones tend not to preserve plants and invertebrates. These seem to require the more anoxic, acidic conditions present in calm lakes and pools for high fidelity preservation, whereas bones preserve well in more oxygen-rich settings.

This makes it difficult to understand the ecosystems of this time – and means our discoveries are especially astonishing. These include the oldest freshwater leech, a record that pushes back the known range of this group by 40 million years, and the oldest water mites by 166 million years.

Other exciting finds include the oldest damsel-fly and oldest stoneflies from Gondwana, as well as a profusion of the tiny, aquatic, immature stages (nymphs) of an extinct group called the Palaeodictyoptera. Many of the insect wings we have found have yet to be identified.

There are also mosses and liverworts, tiny soft plants that were among the first to colonise land. They too, have a very poor fossil record, and we have found both at our site. The liverwort is the oldest in Africa and one of only a few records for the Permian period globally.

There are also mosses and liverworts, tiny soft plants that were among the first to colonise land. They too, have a very poor fossil record, and we have found both at our site. The liverwort is the oldest in Africa and one of only a few records for the Permian period globally.

One of the most exciting finds is the dense accumulations of the male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant, an unbelievably rare occurrence that is shedding light on the evolution and classification of this important coal-forming plant.

Great potential

Great potential

Our work has been slow. Excavations have involved a lot of sitting on spiky rocks in the sun for weeks on end, extracting tiny pieces of mudrock and then examining them with a magnifying hand lens.

The fossil site is still producing new weird and wonderful plants and invertebrates, and will keep us busy for a while. There is also great potential for finding other sites in the region. The thousands of plants and insects we have collected so far are being carefully curated and studied at the Albany Museum in Makhanda. We are keenly aware of the need to conserve this precious part of South Africa’s protected natural heritage.

Our work to better understand the organisms we’re finding provides knowledge about how and when they evolved and interacted as well as about local climate, how their distributions changed through time, how the positions of the continents changed, and the effects of deserts, mountain ranges and seas on the movement and evolution of life.

This is very important when trying to understand extinction events such as the Great Dying, which marked the end of the Permian 252 million years ago. It destroyed most life in the oceans and on land and – in a chilling echo of the current global climate crisis – was driven by hundreds of thousands of years of volcanic activity that produced huge amounts of greenhouse gases, leading to an increase in global temperatures.

Rosemary Prevec, Palaeontologist, Rhodes University

Creationist frauds who want to convince their cult members that the Theory of Evolution is about to be replaced in mainstream science by their childish superstition, and so become the first scientific theory ever to be replaced with an evidence-free superstition involving imaginary supernatural entities, have to keep them ignorant of papers such as this one which has just been published in Communications Biology.

The paper, by a team of scientists led by Rosemary Prevec, a palaeontologist with Rhodes University Department of Botany, and the Department of Earth Science, Albany Museum, Makhanda, South Africa, reports on an exceptionally well preserved collection of fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids and plants - what is known to science as a 'Lagerstätte'. What's more, the formation has 'robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context', in other words, the fossils can be accurately placed in time and the changing geography of the time - some 266–268 million years ago in a river delta, when Earth had just two major landmass known as Gondwana and Laurasia, the northern and southern parts of Pangea respectively, before they were broken up and in some cases forced together by tectonic forces to form today’s major continents.

These fossils enabled the team to reconstruct the ecosystem of the time. An ecosystem is the result of interactions between species of animals and plants in a given area - the fundamental conditions for evolution to occur, as the ecosystem changes in response to internal and external pressures.

The team leader, Rosemary Prevec, has written the following article in The Conversation to explain the background to the discovery and its significance in terms of understanding the evolution of some species and the extinction of others. The Theory of Evolution is, of course, fundamental to research such as this in order to make sense of the observations. Note that nowhere does the author show the slightest doubt about the TOE's value in that understanding.

Her article is reproduced under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Find out more about The Conversation, here.

Exquisite new fossils from South Africa offer a glimpse into a thriving ecosystem 266 million years ago

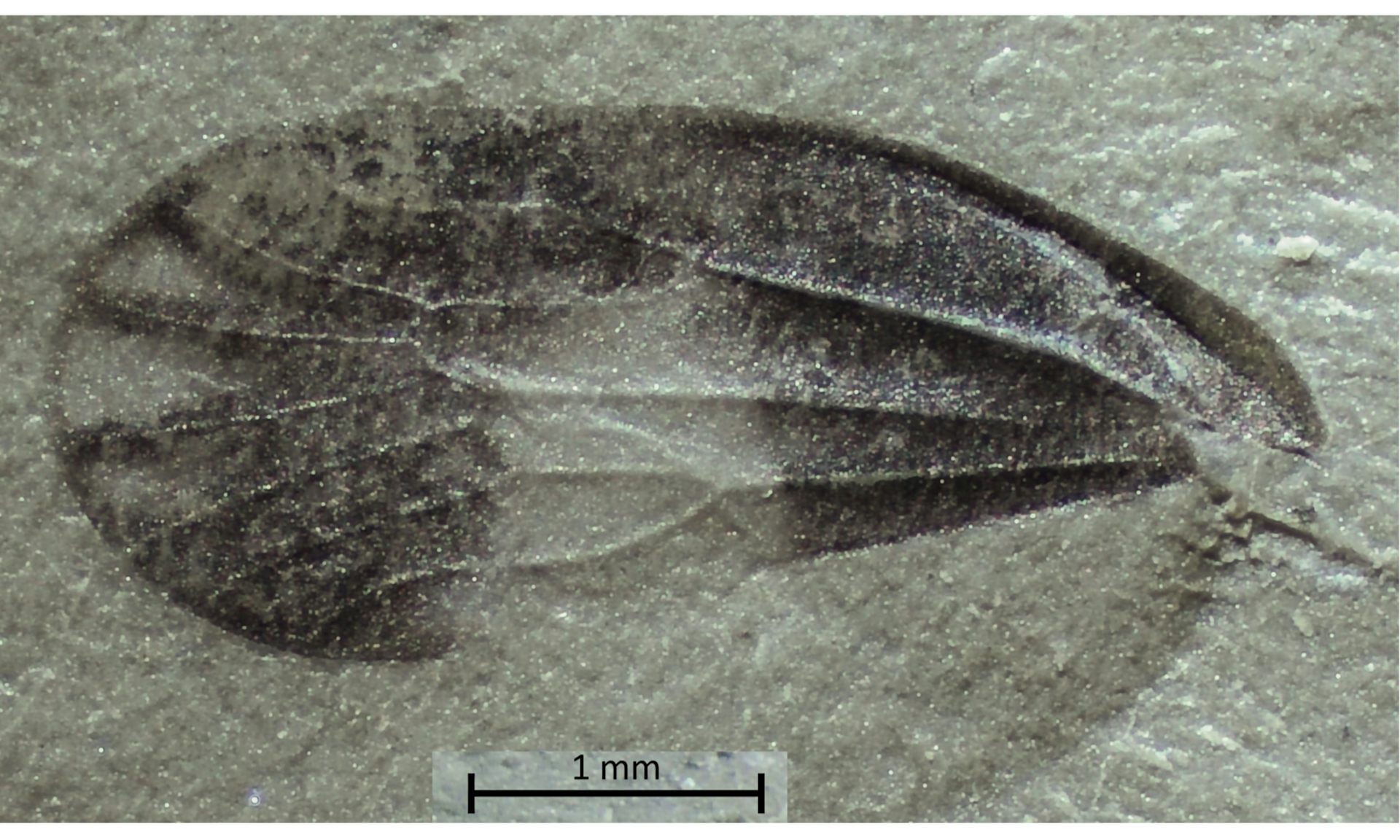

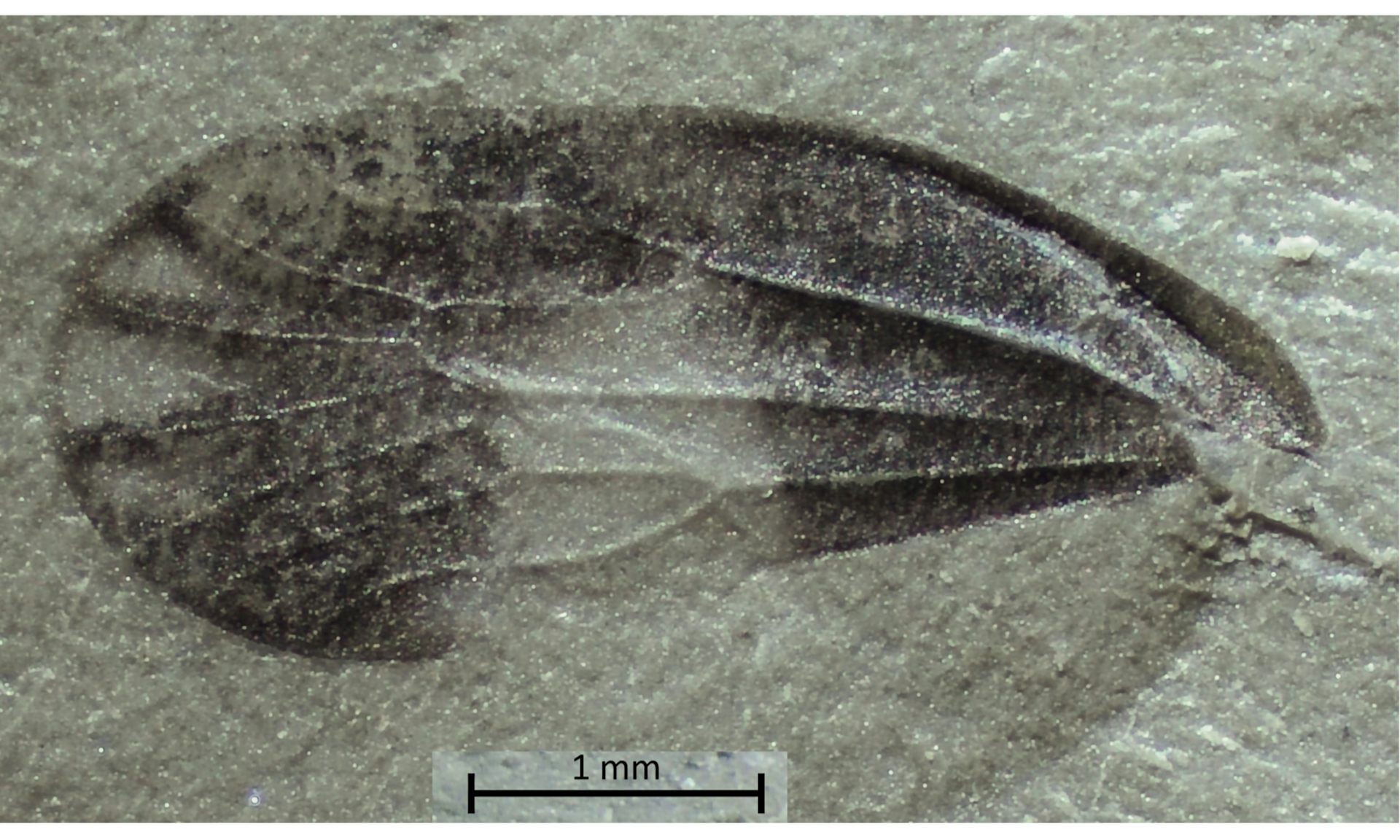

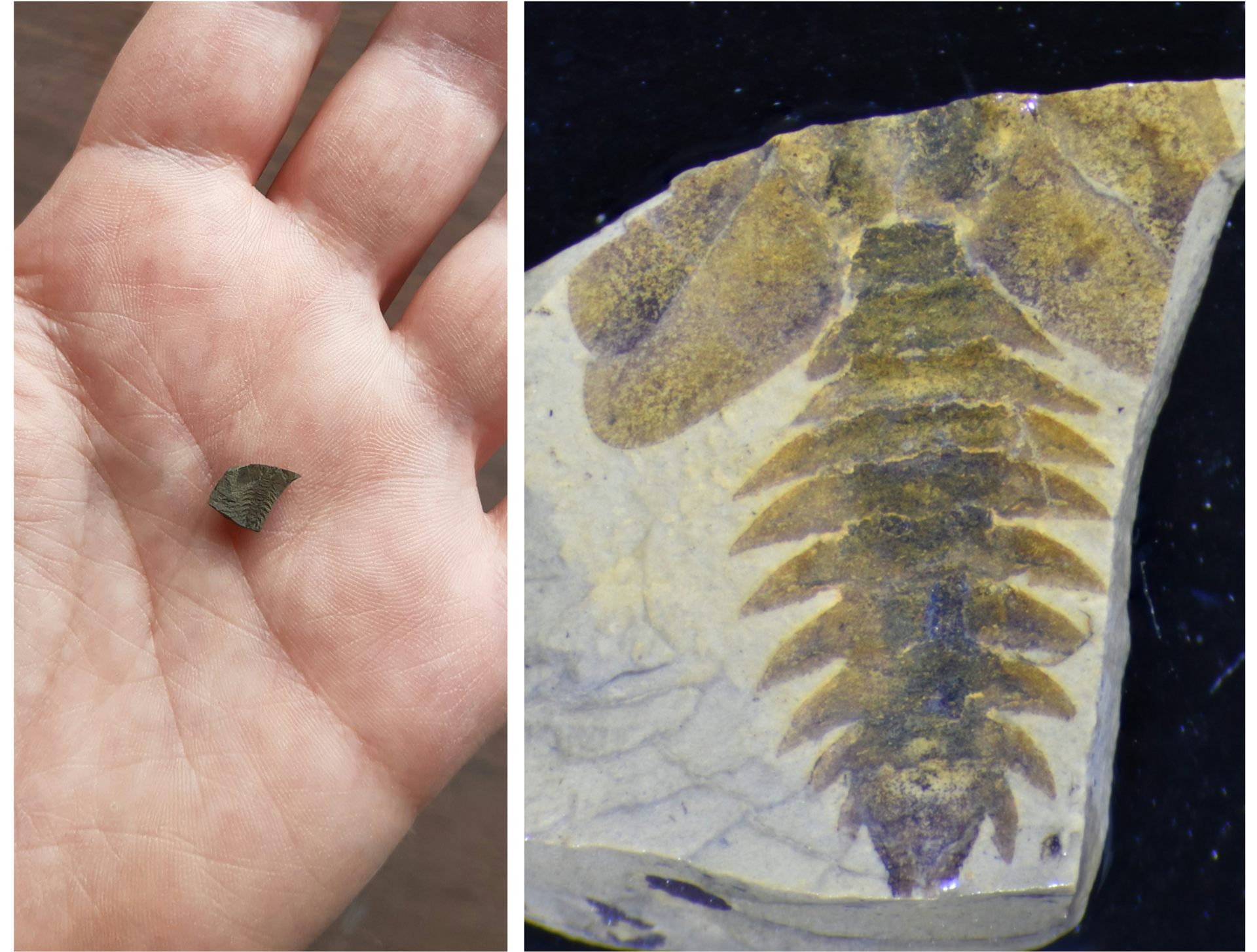

A fossilised insect wing with some of its colouration preserved is just one tiny treasure emerging from the site.

Rose Prevec

Rosemary Prevec, Rhodes University

South Africa is famous for its amazingly rich and diverse fossil record. The country’s rocks document more than 3.5 billion years of life on Earth: ancient forms of bacterial life, the emergence of life onto land, the evolution of seed-producing plants, reptiles, dinosaurs and mammals – and humanity.

Many will be familiar with hominid fossils such as the Australopithecus africanus skull Mrs (or is it Mr?) Ples and the paradigm-shifting Taung child. Less well known and equally important fossils such as the oldest terrestrial vertebrates in the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which document the first steps from the ocean and onto land, have also emerged from South Africa. The country’s wealth of fossils is due in part to the region’s unique geology, which documents 100 million years of nearly continuous deposition in its Karoo Basin.

Fossils also hold clues to climatic shifts, from the great Carboniferous ice age over 300 million years ago, to the huge dunes of blazing Jurassic deserts where dinosaurs roamed 200 million years ago. Scientists can read the devastation of the mass extinction events that destroyed global ecosystems and changed the course of Earth’s history.

But in the race to understand the “big picture” of the evolution of life and to distil its dramatic ups and downs into punchy headlines, it is easy to forget the small and quiet things. Pause, and consider what life looked like on an average day, in a world without humans, mammals, birds, butterflies, flowers, or even dinosaurs. What was it like on the shores of a rippling lake, on a drowsy summer afternoon, 266 million years ago in what’s now the Northern Cape province of South Africa?

The search, and what we found

In a new paper, my colleagues and I provide the first glimpse of such an ecosystem. We have found a profusion of fossils of tiny insects that have never been found before, as well as important plant specimens that are changing our understanding of how they evolved.

Our findings give fresh insights into the effects of extinction events on ecosystems. The subject has taken on great urgency in the face of what scientists are calling the sixth great extinction event, which is being driven by the current trend of global warming.

For the past few years we have been excavating a small, nondescript rock outcrop near Sutherland in the Northern Cape.

This outcrop is yielding untold fossil treasures of plants, insects and other invertebrates that are new to science. These unique fossils, some only a few millimetres long, are telling us about what lived in and around a calm pool on a delta plain during the middle Permian period between 266 million and 268 million years ago. Rocks of this age contain fossils of the oldest therapsids, a group of reptiles that eventually gave rise to the mammals.

Other life of this time included the lizard-like ancestors of tortoises, large amphibians that lurked like crocodiles just below the water surface, and forests dominated by a tree called Glossopteris with an understorey of spore-producing plants such as mosses, ferns and horsetails.

Teams of palaeontologists have discovered and excavated many hundreds of vertebrate fossils in the western and southern Karoo of South Africa that date back to the Permian, including the Sutherland District and surrounding areas. But the kinds of rocks that are rich in vertebrate fossil bones tend not to preserve plants and invertebrates. These seem to require the more anoxic, acidic conditions present in calm lakes and pools for high fidelity preservation, whereas bones preserve well in more oxygen-rich settings.

This makes it difficult to understand the ecosystems of this time – and means our discoveries are especially astonishing. These include the oldest freshwater leech, a record that pushes back the known range of this group by 40 million years, and the oldest water mites by 166 million years.

Other exciting finds include the oldest damsel-fly and oldest stoneflies from Gondwana, as well as a profusion of the tiny, aquatic, immature stages (nymphs) of an extinct group called the Palaeodictyoptera. Many of the insect wings we have found have yet to be identified.

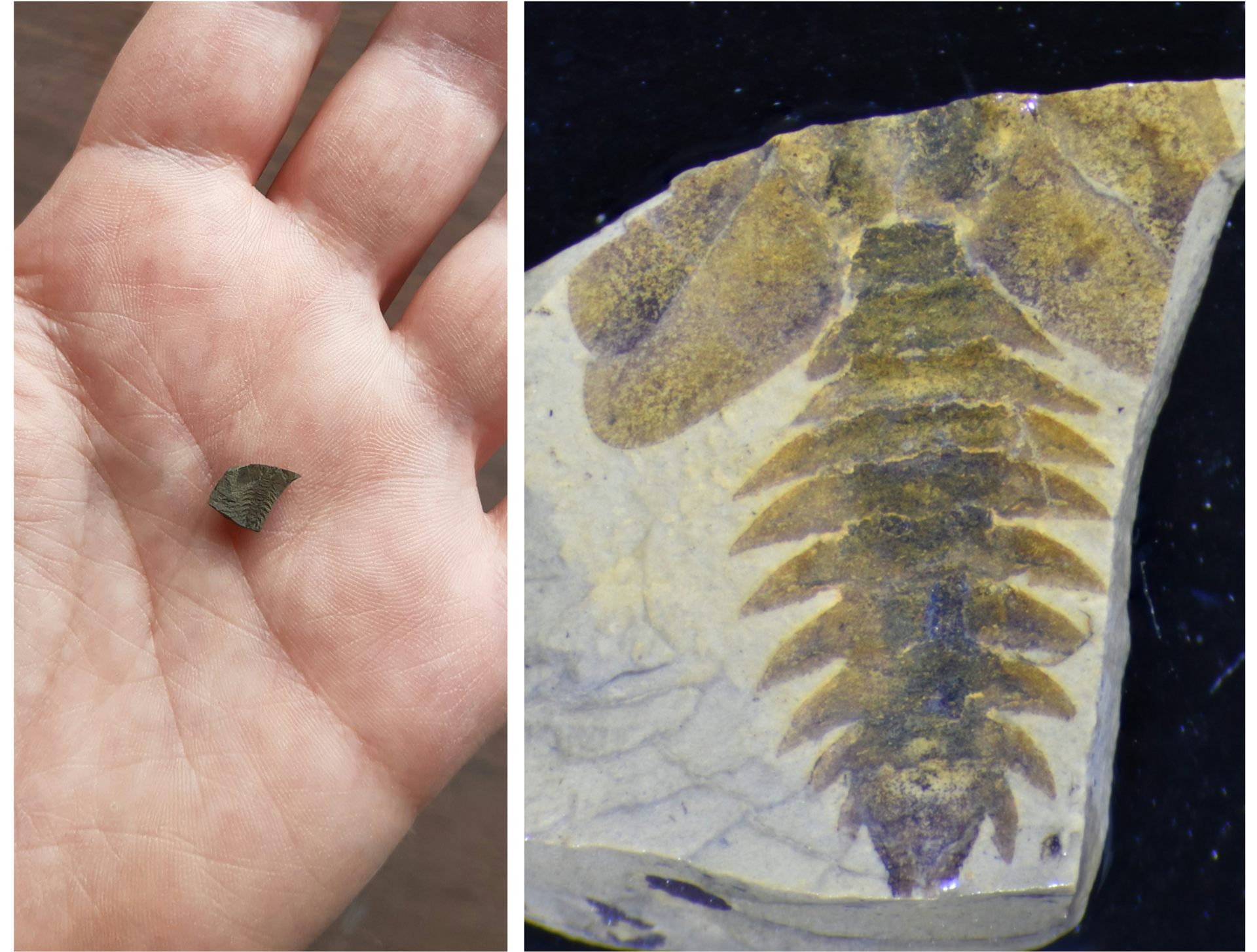

A fossil of an insect nymph - so tiny that it is dwarfed by a human hand - and, on the right, seen under a microscope.

Credit: Rose Prevec

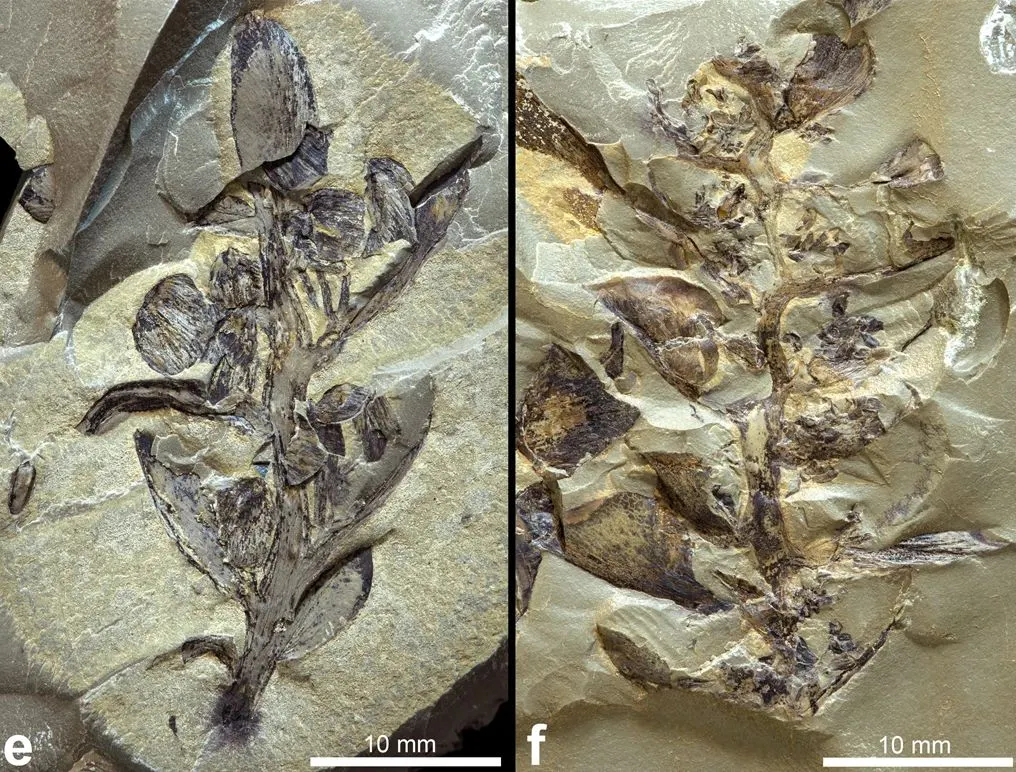

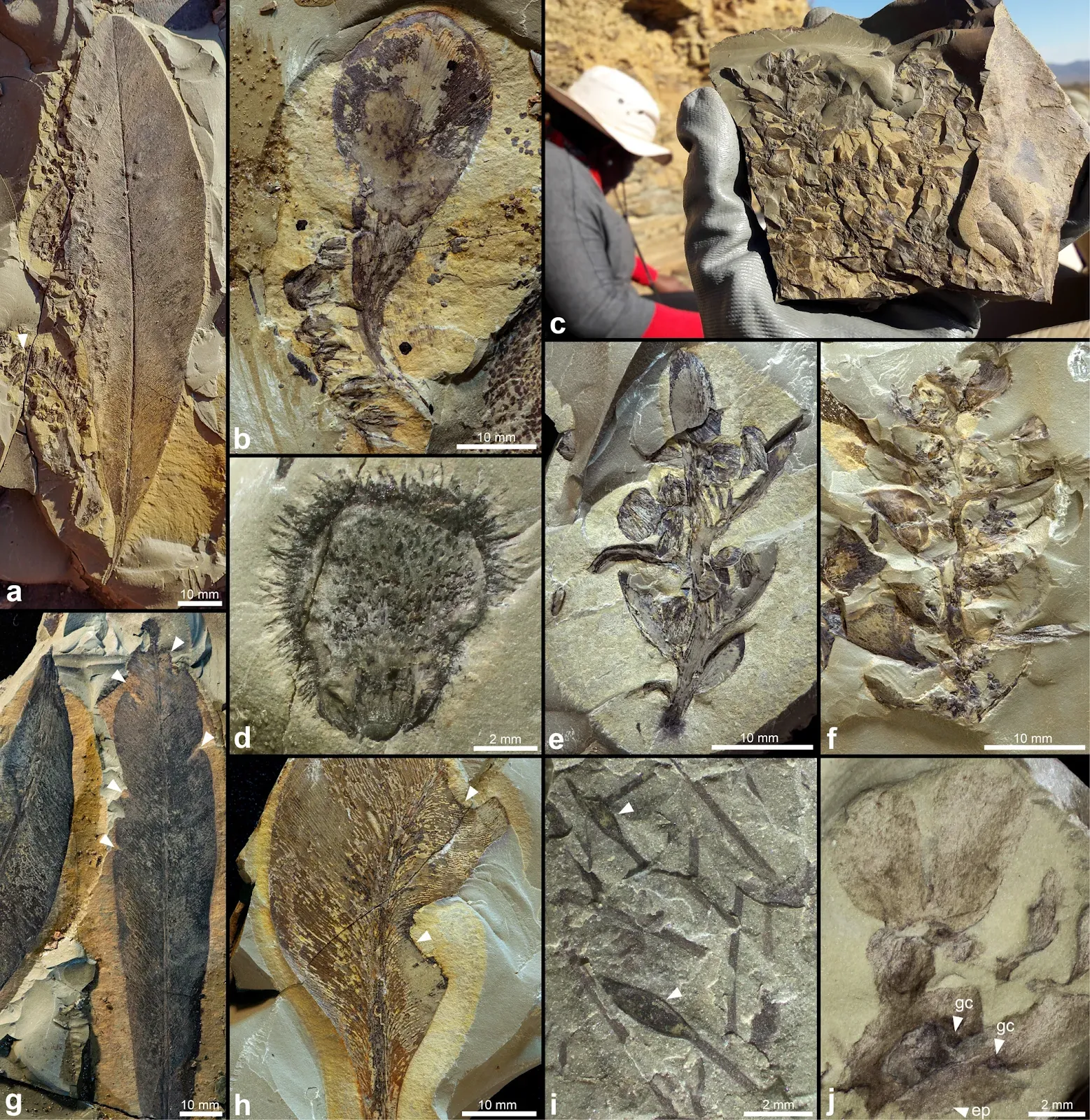

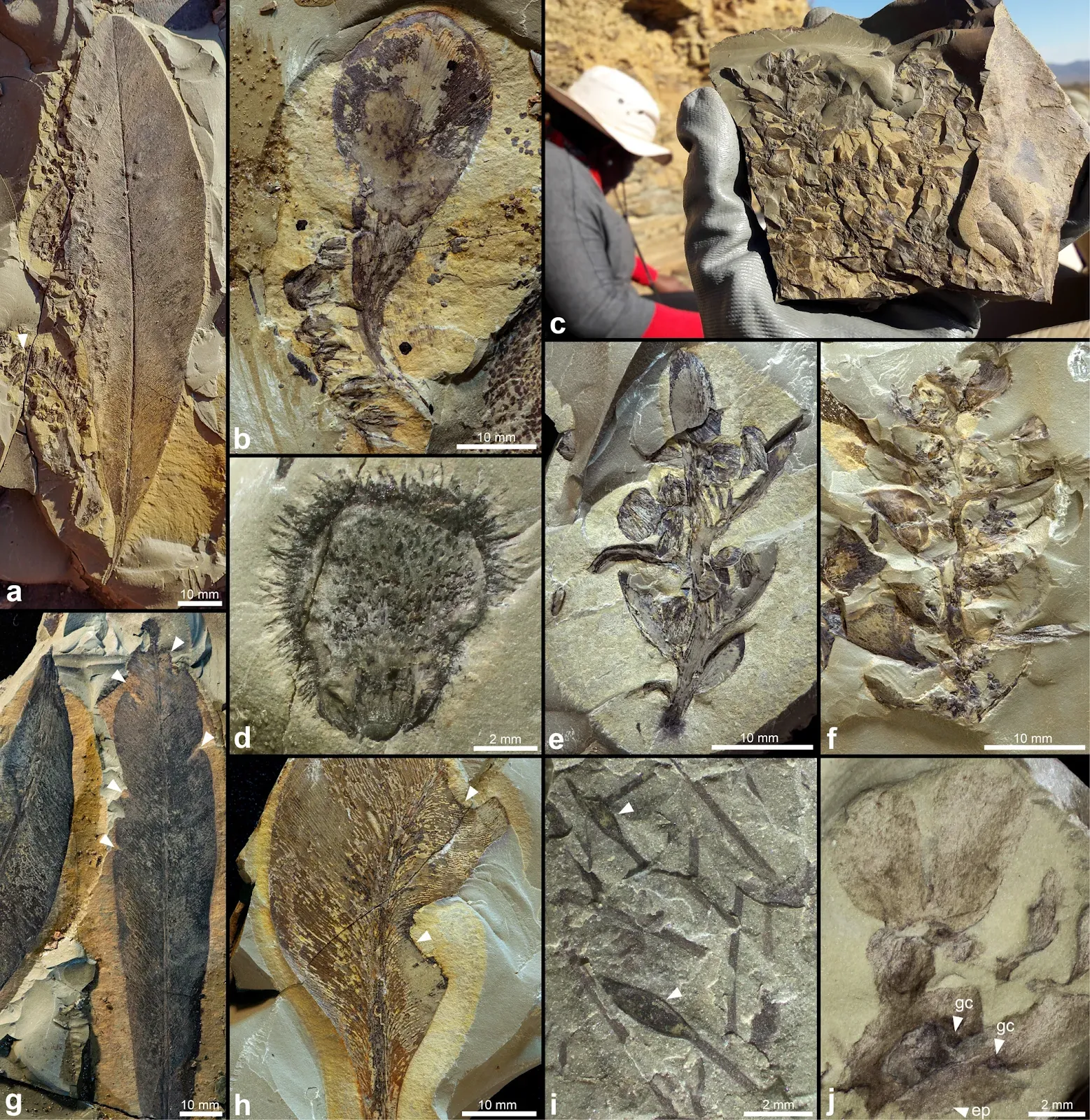

One of the most exciting finds is the dense accumulations of the male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant, an unbelievably rare occurrence that is shedding light on the evolution and classification of this important coal-forming plant.

Male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant.

Credit: Rose Prevec

Our work has been slow. Excavations have involved a lot of sitting on spiky rocks in the sun for weeks on end, extracting tiny pieces of mudrock and then examining them with a magnifying hand lens.

The fossil site is still producing new weird and wonderful plants and invertebrates, and will keep us busy for a while. There is also great potential for finding other sites in the region. The thousands of plants and insects we have collected so far are being carefully curated and studied at the Albany Museum in Makhanda. We are keenly aware of the need to conserve this precious part of South Africa’s protected natural heritage.

Our work to better understand the organisms we’re finding provides knowledge about how and when they evolved and interacted as well as about local climate, how their distributions changed through time, how the positions of the continents changed, and the effects of deserts, mountain ranges and seas on the movement and evolution of life.

This is very important when trying to understand extinction events such as the Great Dying, which marked the end of the Permian 252 million years ago. It destroyed most life in the oceans and on land and – in a chilling echo of the current global climate crisis – was driven by hundreds of thousands of years of volcanic activity that produced huge amounts of greenhouse gases, leading to an increase in global temperatures.

Rosemary Prevec, Palaeontologist, Rhodes University

Fig. 4: Key plant fossil discoveries from the Onder Karoo locality.

a Glossopteris leaf with abundant platyspermic seeds to the left. Arrow indicates adjacent Lidgettonia sp. 1 fructification, the likely source of the seeds. b Lidgettonia sp. 1: large scale leaf with at least five pairs of cupules attached. c Slab showing mixed mat of male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant. d New dictyopteridean, seed-bearing glossopterid fructification Ottokaria. e Female cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Lidgettonia sp. 2 fertiligers attached to a shoot. f Male cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Eretmonia sp. polleniferous scales attached to a shoot. g Glossopteris leaves, arrows indicate sites of margin-feeding by insects. h Glossopteris leaf with arrows indicating large excisions caused by insect feeding, note pronounced staining of plant reaction tissue. i Probable moss sporophytes, arrows indicate moss capsules. j Thallose liverwort with dichotomous branching, notched termini, hydroids, typical epidermal patterning (ep, arrow) and possible gemma cups (gc, arrows).

a Glossopteris leaf with abundant platyspermic seeds to the left. Arrow indicates adjacent Lidgettonia sp. 1 fructification, the likely source of the seeds. b Lidgettonia sp. 1: large scale leaf with at least five pairs of cupules attached. c Slab showing mixed mat of male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant. d New dictyopteridean, seed-bearing glossopterid fructification Ottokaria. e Female cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Lidgettonia sp. 2 fertiligers attached to a shoot. f Male cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Eretmonia sp. polleniferous scales attached to a shoot. g Glossopteris leaves, arrows indicate sites of margin-feeding by insects. h Glossopteris leaf with arrows indicating large excisions caused by insect feeding, note pronounced staining of plant reaction tissue. i Probable moss sporophytes, arrows indicate moss capsules. j Thallose liverwort with dichotomous branching, notched termini, hydroids, typical epidermal patterning (ep, arrow) and possible gemma cups (gc, arrows).

Fig. 5: A selection of newly discovered invertebrate fossils from the Onder Karoo locality.

a AM14859: exuviae of a nymph (Palaeodictyopterida). b AM13265: stonefly nymph (Plecoptera). c AM11348: cluster of plecopteran nymph exuviae associated with glossopterid seeds. d AM11296: distal fragment of a wing of Afrozygopteron inexpectatus45, a Protozygoptera (an early damselfly-like Odonatoptera), with sclerotized costo-apical pterostigma (arrow). e AM11389: forewing of an ‘ice crawler’, Colubrosopterum karooensis (a new genus of ‘Grylloblattodea’, Liomopteridae46). f AM14864d: two forewings of Protelytoptera. g AM14864e: two forewings of Anthracoptilidae (Paoliida). h AM14858ab: composite image of part and counterpart of a hemipteran forewing (Prosbolidae). i AM11298a: hemipteran forewing with pattern of wing colouration preserved (Scytinopteridae). j AM11157a: large forewing of a cicadamorph with pattern of colouration preserved (Hemiptera, Pereboriidae). k terrestrial nymph/nymph exuviae (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha). l annelid worm, probable Clitellata (leech) with circular sucker (arrow). m AM11282b: elytron of a beetle with punctate ornamentation (Coleoptera, Permocupedidae). n AM14856: water mite (Acari, Hydrachnidia).

a AM14859: exuviae of a nymph (Palaeodictyopterida). b AM13265: stonefly nymph (Plecoptera). c AM11348: cluster of plecopteran nymph exuviae associated with glossopterid seeds. d AM11296: distal fragment of a wing of Afrozygopteron inexpectatus45, a Protozygoptera (an early damselfly-like Odonatoptera), with sclerotized costo-apical pterostigma (arrow). e AM11389: forewing of an ‘ice crawler’, Colubrosopterum karooensis (a new genus of ‘Grylloblattodea’, Liomopteridae46). f AM14864d: two forewings of Protelytoptera. g AM14864e: two forewings of Anthracoptilidae (Paoliida). h AM14858ab: composite image of part and counterpart of a hemipteran forewing (Prosbolidae). i AM11298a: hemipteran forewing with pattern of wing colouration preserved (Scytinopteridae). j AM11157a: large forewing of a cicadamorph with pattern of colouration preserved (Hemiptera, Pereboriidae). k terrestrial nymph/nymph exuviae (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha). l annelid worm, probable Clitellata (leech) with circular sucker (arrow). m AM11282b: elytron of a beetle with punctate ornamentation (Coleoptera, Permocupedidae). n AM14856: water mite (Acari, Hydrachnidia).

More detail is given in the abstract to the team's open access paper in Communications Biology:

AbstractAnd another research paper casually refutes the Creationist lie that the TOE is being increasingly rejected by serious scientists.

Continental ecosystems of the middle Permian Period (273–259 million years ago) are poorly understood. In South Africa, the vertebrate fossil record is well documented for this time interval, but the plants and insects are virtually unknown, and are rare globally. This scarcity of data has hampered studies of the evolution and diversification of life, and has precluded detailed reconstructions and analyses of ecosystems of this critical period in Earth’s history. Here we introduce a new locality in the southern Karoo Basin that is producing exceptionally well-preserved and abundant fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids, and plants. Within a robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context, this Konservat- and Konzentrat-Lagerstätte offers a unique opportunity for the study and reconstruction of a southern Gondwanan deltaic ecosystem that thrived 266–268 million years ago, and will serve as a high-resolution ecological baseline towards a better understanding of Permian extinction events.

Prevec, R., Nel, A., Day, M.O. et al.

South African Lagerstätte reveals middle Permian Gondwanan lakeshore ecosystem in exquisite detail.

Commun Biol 5, 1154 (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-022-04132-y

Copyright: © 2022 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Friday, 25 November 2022

Creationism in Crisis - How a Small Cluster of Genes Made us Human

Human Evolution Wasn’t Just the Sheet Music, But How it Was Played | Duke Today

A group of researchers from Duke University, Durham, NC, USA, has identified a group of human DNA sequences that drive changes in brain development, digestive tract length and immunity that evolved quickly following our split from the common ancestor we share with the chimpanzees, but before we diverged from Neanderthals. In other words, these probably arose sometime in the last 7.5 million years which means they were probably present in Home erectus and maybe the Australopithecines.

A group of researchers from Duke University, Durham, NC, USA, has identified a group of human DNA sequences that drive changes in brain development, digestive tract length and immunity that evolved quickly following our split from the common ancestor we share with the chimpanzees, but before we diverged from Neanderthals. In other words, these probably arose sometime in the last 7.5 million years which means they were probably present in Home erectus and maybe the Australopithecines.

The DNA sequences in question act as regulatory switches, turning other genes on and off to regulate development in the embryo.

As the news item in Duke Today explains:

The fluorescent glow of mouse brain cells on the right indicates the effectiveness of a human-derived gene enhancer, HAQER0059, versus a 6 million year old version of the enhancer at left.

Riley Mangan, Duke University

The DNA sequences in question act as regulatory switches, turning other genes on and off to regulate development in the embryo.

As the news item in Duke Today explains:

Our brains are bigger, and are guts are shorter than our ape peers.

“A lot of the traits that we think of as uniquely human, and human-specific, probably appear during that time period,” in the 7.5 million years since the split with the common ancestor we share with the chimpanzee, said Craig Lowe, Ph.D., an assistant professor of molecular genetics and microbiology in the Duke School of Medicine.

Specifically, the DNA sequences in question, which the researchers have dubbed Human Ancestor Quickly Evolved Regions (HAQERS), pronounced like hackers, regulate genes. They are the switches that tell nearby genes when to turn on and off. The findings appear Nov.23 in the journal CELL.

The rapid evolution of these regions of the genome seems to have served as a fine-tuning of regulatory control, Lowe said. More switches were added to the human operating system as sequences developed into regulatory regions, and they were more finely tuned to adapt to environmental or developmental cues. By and large, those changes were advantageous to our species.

“They seem especially specific in causing genes to turn on, we think just in certain cell types at certain times of development, or even genes that turn on when the environment changes in some way,” Lowe said.

A lot of this genomic innovation was found in brain development and the GI tract. “We see lots of regulatory elements that are turning on in these tissues,” Lowe said. “These are the tissues where humans are refining which genes are expressed and at what level.”

Today, our brains are larger than other apes, and our guts are shorter. “People have hypothesized that those two are even linked, because they are two really expensive metabolic tissues to have around,” Lowe said. “I think what we’re seeing is that there wasn’t really one mutation that gave you a large brain and one mutation that really struck the gut, it was probably many of these small changes over time.”

To produce the new findings, Lowe’s lab collaborated with Duke colleagues Tim Reddy, an associate professor of biostatistics and bioinformatics, and Debra Silver, an associate professor of molecular genetics and microbiology to tap their expertise. Reddy’s lab is capable of looking at millions of genetic switches at once and Silver is watching switches in action in developing mouse brains.

“Our contribution was, if we could bring both of those technologies together, then we could look at hundreds of switches in this sort of complex developing tissue, which you can't really get from a cell line,” Lowe said.

“We wanted to identify switches that were totally new in humans,” Lowe said. Computationally, they were able to infer what the human-chimp ancestor’s DNA would have been like, as well as the extinct Neanderthal and Denisovan lineages. The researchers were able to compare the genome sequences of these other post-chimpanzee relatives thanks to databases created from the pioneering work of 2022 Nobel laureate Svante Pääbo.

“So, we know the Neanderthal sequence, but let's test that Neanderthal sequence and see if it can really turn on genes or not,” which they did dozens of times.

“And we showed that, whoa, this really is a switch that turns on and off genes,” Lowe said. “It was really fun to see that new gene regulation came from totally new switches, rather than just sort of rewiring switches that already existed.”

Along with the positive traits that HAQERs gave humans, they can also be implicated in some diseases.

Most of us have remarkably similar HAQER sequences, but there are some variances, “and we were able to show that those variants tend to correlate with certain diseases,” Lowe said, namely hypertension, neuroblastoma, unipolar depression, bipolar depression and schizophrenia. The mechanisms of action aren’t known yet, and more research will have to be done in these areas, Lowe said.

“Maybe human-specific diseases or human-specific susceptibilities to these diseases are going to be preferentially mapped back to these new genetic switches that only exist in humans,” Lowe said.

The authors give more technical detail in the Highlights and Summary sections of their open access paper in Cell:

HighlightsAnd once again, with monotonous regularity, a group of researchers refutes creationism, and especially the childish claim that the Theory of Evolution is a theory in crisis, about to be overthrown by the superstition of intelligent [sic] design Creationism.

- HAQERs are human genomic regions highly divergent from the human-chimpanzee ancestor

- HAQERs evolved under elevated mutation rates and positive selection

- HAQERs are enriched for bivalent chromatin and disease-linked variation

- HAQER divergence forged hominin-unique enhancers in the developing cerebral cortex

Summary

Searches for the genetic underpinnings of uniquely human traits have focused on human-specific divergence in conserved genomic regions, which reflects adaptive modifications of existing functional elements. However, the study of conserved regions excludes functional elements that descended from previously neutral regions. Here, we demonstrate that the fastest-evolved regions of the human genome, which we term “human ancestor quickly evolved regions” (HAQERs), rapidly diverged in an episodic burst of directional positive selection prior to the human-Neanderthal split, before transitioning to constraint within hominins. HAQERs are enriched for bivalent chromatin states, particularly in gastrointestinal and neurodevelopmental tissues, and genetic variants linked to neurodevelopmental disease. We developed a multiplex, single-cell in vivo enhancer assay to discover that rapid sequence divergence in HAQERs generated hominin-unique enhancers in the developing cerebral cortex. We propose that a lack of pleiotropic constraints and elevated mutation rates poised HAQERs for rapid adaptation and subsequent susceptibility to disease.

Mangan, Riley J.; Alsina, Fernando C.; Mosti, Federica; Sotelo-Fonseca, Jesús Emiliano; Snellings, Daniel A.; Au, Eric H.; Carvalho, Juliana; Sathyan, Laya; Johnson, Graham D.; Reddy, Timothy E.; Silver, Debra L.; Lowe, Craig B.

Adaptive sequence divergence forged new neurodevelopmental enhancers in humans

Cell; 185(24), 4587-4603.e23. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.10.016

Copyright: © 2022 The authors.

Published by Elsevier Inc. Open access

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Creationism in Crisis - Genetics Confirms Common Ancestry of 'Oddball' Fungi

Genome studies uncover a new branch in fungal evolution | Folio

In a stunning example of the power of the Theory of Evolution (TOE) to explain otherwise puzzling observations, a team of scientists led by principal investigator, Toby Spribille an associate professor in Alberta University's Department of Biological Sciences, has shown how some 600 'oddball' fungi share a common ancestor that lived about 300 million years ago.

The problem was that the usual Linnaean method of classification, using the appearance of organisms, some 600 strange fungi were difficult to fit into any single taxon.

In addition to this obvious confirmation that the TOE is the basis of biology, confirmed by genetics, there is the additional embarrassment for Creationists in the finding that the diversity of this group is due to a loss of genetic information, made possible by a symbiotic existence, where the co-symbiont has taken on some of the basic functions. That a loss of information is always detrimental and evolution requires an increase in information is now a central dogma of Creationism that flies in the face of evidence such as this.

The Alberta University news release explain the research:

The earth tongue is one of 600 “oddball” fungi that were found to share a common ancestor dating back 300 million years, according to University of Alberta researchers.

Photo: Alan Rockefeller, (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

In a stunning example of the power of the Theory of Evolution (TOE) to explain otherwise puzzling observations, a team of scientists led by principal investigator, Toby Spribille an associate professor in Alberta University's Department of Biological Sciences, has shown how some 600 'oddball' fungi share a common ancestor that lived about 300 million years ago.

The problem was that the usual Linnaean method of classification, using the appearance of organisms, some 600 strange fungi were difficult to fit into any single taxon.

In addition to this obvious confirmation that the TOE is the basis of biology, confirmed by genetics, there is the additional embarrassment for Creationists in the finding that the diversity of this group is due to a loss of genetic information, made possible by a symbiotic existence, where the co-symbiont has taken on some of the basic functions. That a loss of information is always detrimental and evolution requires an increase in information is now a central dogma of Creationism that flies in the face of evidence such as this.

The Alberta University news release explain the research:

Thursday, 24 November 2022

Live Presentation - Unintelligent Design

A first for me. Come and participate!

Saturday 26 Nov, 2022. 20:30 GMT, 15;30 EST, 12:30 PST, 22:30 CAT.

Wednesday, 23 November 2022

Creationism in Crisis - Modern Humans Are Not The First To Appreciate Art

How we discovered that Neanderthals could make art

Creationist superstition says that human beings were made somehow differently to all the other animals, although they can never say how, exactly. Some believe only humans have an unproven and undefined magic entity living inside their body, called a 'soul', but other animals don't have this magic ingredient; others argue that animals also have this magic ingredient. They disagree endlessly on this point simply because they have no facts by which to determine the truth. If the 'soul' was detectable, the issue could be resolved easily and quickly. As it is, all they have is dogma.

But whatever their view of who has a magic soul and who doesn't, high on their list of abilities that humans have that other animals allegedly don't have will be aesthetic appreciation of art, music, love, etc. Some attribute this to the magic soul thing, others are happy to regard it as part of some unique aspect of human psychology, neuro-physiology, and/or genetics, so, of course, any evidence that another species has aesthetic appreciation is a major embarrassment for them.

However, with regard to artistic appreciation, there is now strong evidence that our cousin species, Neanderthals, could make artistic or symbolic designs, so, since we are related through a common ancestor - probably Homo heidelbergensis or Homo erectus, if indeed they were different species, it is highly likely that at least the potential for making symbolic drawings was present in that ancestor.

How do we know Neanderthals could make art?

In this article reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, Dr Chris Standish, Postdoctoral Fellow of Archaeology, and Professor Alistair Pike, Professor of Archaeological Sciences, both of Southampton University, Hampshire, UK, present the evidence.

The article is reformatted for stylistic consistence. The original can be read here:

Chris Standish, University of Southampton and Alistair Pike, University of Southampton

What makes us human? A lot of people would argue it is the ability of our species to engage in complex behaviour such as using language, creating art and being moral. But when and how did we first become “human” in this sense? While skeletal remains can reveal when our ancestors first became “anatomically modern”, it is much harder for scientists to decipher when the human lineage became “behaviourally modern”.

One of the key traits of behavioural modernity is the capacity to use, interpret and respond to symbols. We know that Homo sapiens have been doing this for at least 80,000 years. But its predecessor in parts of Eurasia, the Neanderthal, a human ancestor that became extinct around 40,000 years ago, has traditionally been regarded as uncultured and behaviourally inferior. Now our new study, published in Science, has challenged this view by showing that Neanderthals were able to create cave art.

The earliest examples of symbolic behaviour in African Homo sapiens populations include the use of mineral pigments and shell beads – presumably for body adornment and expressions of identity.

However, evidence for such behaviour by other human species is far more contentious. There are some tantalising clues that Neanderthals in Europe also used body ornamentation around 40,000 to 45,000 years ago. But scientists have so far argued that this must have been inspired by the modern humans who had just arrived there – we know that humans and Neanderthals interacted and even interbred.

Cave art is seen as a more sophisticated example of symbolic behaviour than body ornamentation, and has traditionally been thought of as a defining characteristic of Homo sapiens. In fact, most researchers believe that the cave art found in Europe and dating back over 40,000 years must have been painted by modern humans, even though Neanderthals were around at this time.

Cave art is seen as a more sophisticated example of symbolic behaviour than body ornamentation, and has traditionally been thought of as a defining characteristic of Homo sapiens. In fact, most researchers believe that the cave art found in Europe and dating back over 40,000 years must have been painted by modern humans, even though Neanderthals were around at this time.

Dating cave art

Unfortunately, we have a poor understanding of the origins of cave art, primarily due to difficulties in accurately dating it. Archaeologists typically rely on radiocarbon dating when trying to date events from our past, but this requires the sample to contain organic material.

Cave art, however, is often produced from mineral-based pigments which contain no organics, meaning radiocarbon dating isn’t possible. Even when when it is – such as when a charcoal-based pigment has been used – it suffers from issues of contamination which can lead to inaccurate dates. It is also a destructive technique, as the sample of pigment has to be taken from the art itself.

Cave art, however, is often produced from mineral-based pigments which contain no organics, meaning radiocarbon dating isn’t possible. Even when when it is – such as when a charcoal-based pigment has been used – it suffers from issues of contamination which can lead to inaccurate dates. It is also a destructive technique, as the sample of pigment has to be taken from the art itself.

Uranium-thorium dating of carbonate minerals is often a better option. This well-established geochronological technique measures the natural decay of trace amounts of uranium to date the mineralisation of recent geological formations such as stalagmites and stalactites – collectively known as “speleothems”. Tiny speleothem formations are often found on top of cave paintings, making it possible to use this technique to constrain the age of cave art without impacting on the art itself.

A new era

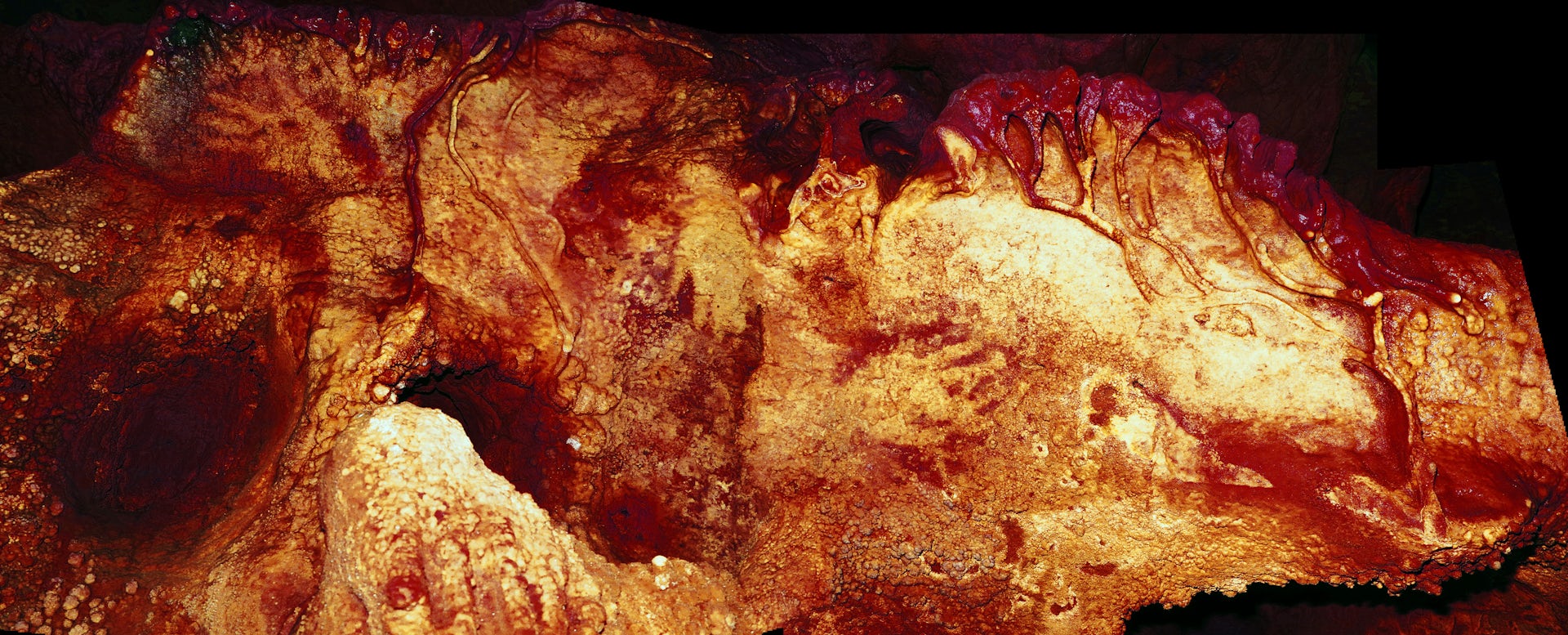

We used uranium-thorium dating to investigate cave art from three previously discovered sites in Spain. In La Pasiega, northern Spain, we showed that a red linear motif is older than 64,800 years. In Ardales, southern Spain, various red painted stalagmite formations date to different episodes of painting, including one between 45,300 and 48,700 years ago, and another before 65,500 years ago. In Maltravieso in western central Spain, we showed a red hand stencil is older than 66,700 years.

These results demonstrate that cave art was being created in all three sites at least 20,000 years prior to the arrival of Homo sapiens in western Europe. They show for the first time that Neanderthals did produce cave art, and that is was not a one off event. It was created in caves across the full breadth of Spain, and at Ardales it occurred at multiple times over at least an 18,000-year period. Excitingly, the types of paintings produced (red lines, dots and hand stencils) are also found in caves elsewhere in Europe so it would not be surprising if some of these were made by Neanderthals, too.

These results demonstrate that cave art was being created in all three sites at least 20,000 years prior to the arrival of Homo sapiens in western Europe. They show for the first time that Neanderthals did produce cave art, and that is was not a one off event. It was created in caves across the full breadth of Spain, and at Ardales it occurred at multiple times over at least an 18,000-year period. Excitingly, the types of paintings produced (red lines, dots and hand stencils) are also found in caves elsewhere in Europe so it would not be surprising if some of these were made by Neanderthals, too.

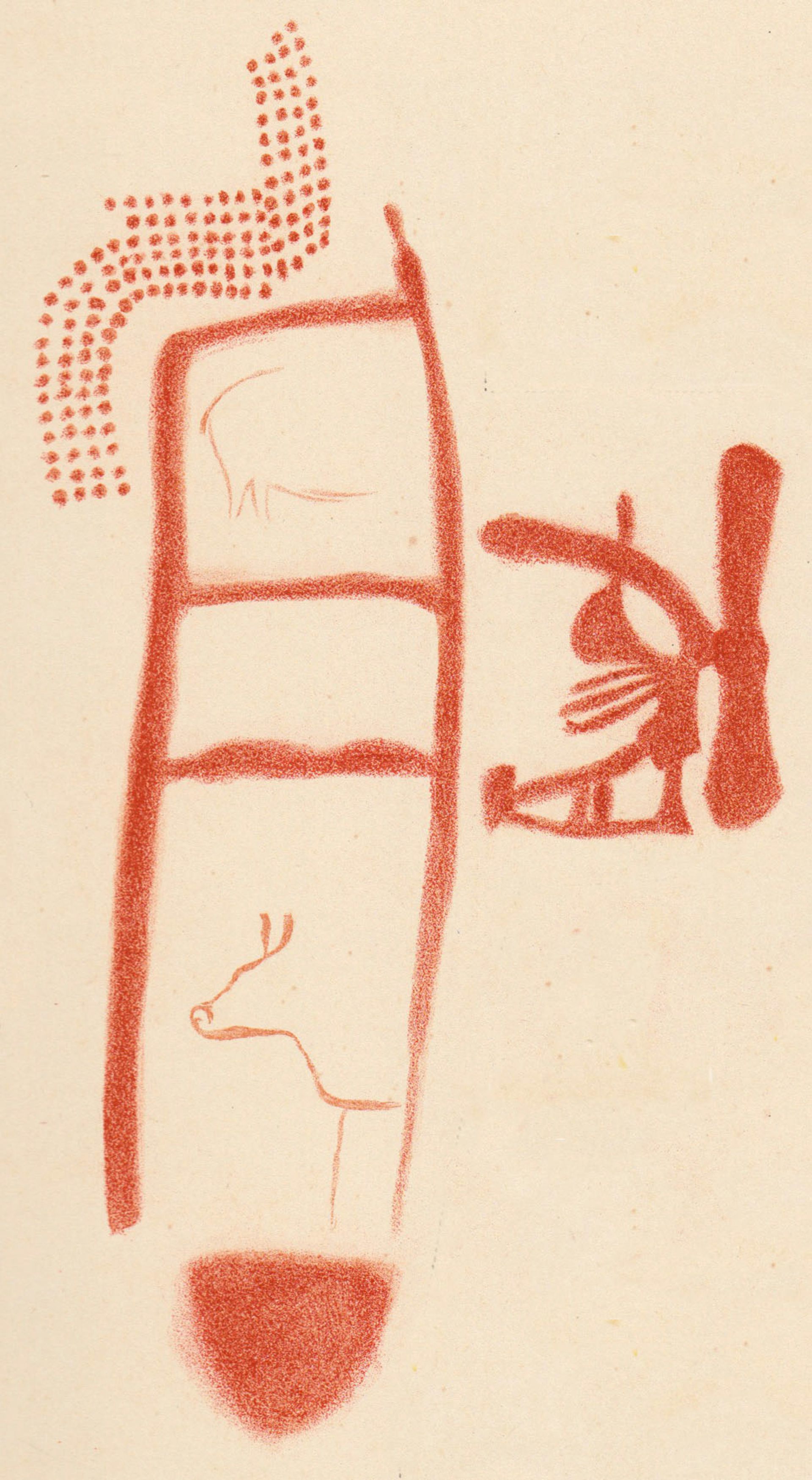

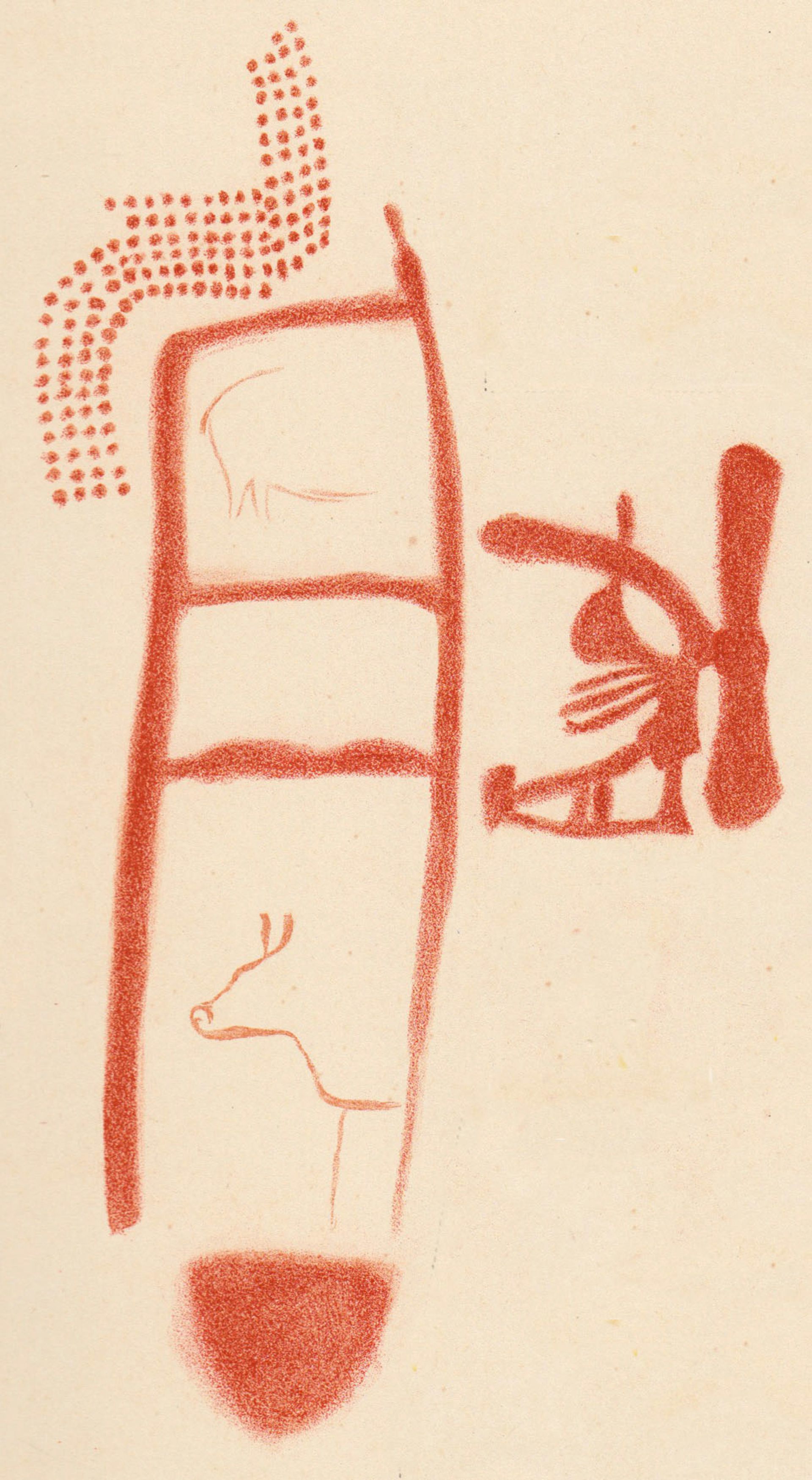

We don’t know the exact meaning of the paintings, such as the ladder shape, but we do know they must have been important to Neanderthals. Some of them were painted in pitch black areas deep in the caves – requiring the preparation of a light source as well as the pigment. The locations appear deliberately selected, the ceilings of low overhangs or impressive stalagmite formations. These must have been meaningful symbols in meaningful places.

We don’t know the exact meaning of the paintings, such as the ladder shape, but we do know they must have been important to Neanderthals. Some of them were painted in pitch black areas deep in the caves – requiring the preparation of a light source as well as the pigment. The locations appear deliberately selected, the ceilings of low overhangs or impressive stalagmite formations. These must have been meaningful symbols in meaningful places.

Our results are tremendously significant, both for our understanding of Neanderthals and for the emergence of behavioural complexity in the human lineage. Neanderthals undoubtedly had the capacity for symbolic behaviour, much like contemporaneous modern human populations residing in Africa.

To understand how behavioural modernity arose, we now need to shift our focus back to periods when Homo sapiens and Neanderthals interacted and to the period of their last common ancestor. The most likely candidate for this ancestor is Homo heidelbergensis, which lived over half a million years ago.

It is perhaps also now time that we move beyond a focus on what makes Homo sapiens and Neanderthals different. Modern humans may have “replaced” Neanderthals, but it is becoming increasingly clear that Neanderthals had similar cognitive and behavioural abilities – they were, in fact, equally “human”.

Chris Standish, Postdoctoral Fellow of Archaeology, University of Southampton and Alistair Pike, Professor of Archaeological Sciences, University of Southampton

Creationist superstition says that human beings were made somehow differently to all the other animals, although they can never say how, exactly. Some believe only humans have an unproven and undefined magic entity living inside their body, called a 'soul', but other animals don't have this magic ingredient; others argue that animals also have this magic ingredient. They disagree endlessly on this point simply because they have no facts by which to determine the truth. If the 'soul' was detectable, the issue could be resolved easily and quickly. As it is, all they have is dogma.

But whatever their view of who has a magic soul and who doesn't, high on their list of abilities that humans have that other animals allegedly don't have will be aesthetic appreciation of art, music, love, etc. Some attribute this to the magic soul thing, others are happy to regard it as part of some unique aspect of human psychology, neuro-physiology, and/or genetics, so, of course, any evidence that another species has aesthetic appreciation is a major embarrassment for them.

However, with regard to artistic appreciation, there is now strong evidence that our cousin species, Neanderthals, could make artistic or symbolic designs, so, since we are related through a common ancestor - probably Homo heidelbergensis or Homo erectus, if indeed they were different species, it is highly likely that at least the potential for making symbolic drawings was present in that ancestor.

How do we know Neanderthals could make art?

In this article reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, Dr Chris Standish, Postdoctoral Fellow of Archaeology, and Professor Alistair Pike, Professor of Archaeological Sciences, both of Southampton University, Hampshire, UK, present the evidence.

The article is reformatted for stylistic consistence. The original can be read here:

How we discovered that Neanderthals could make art

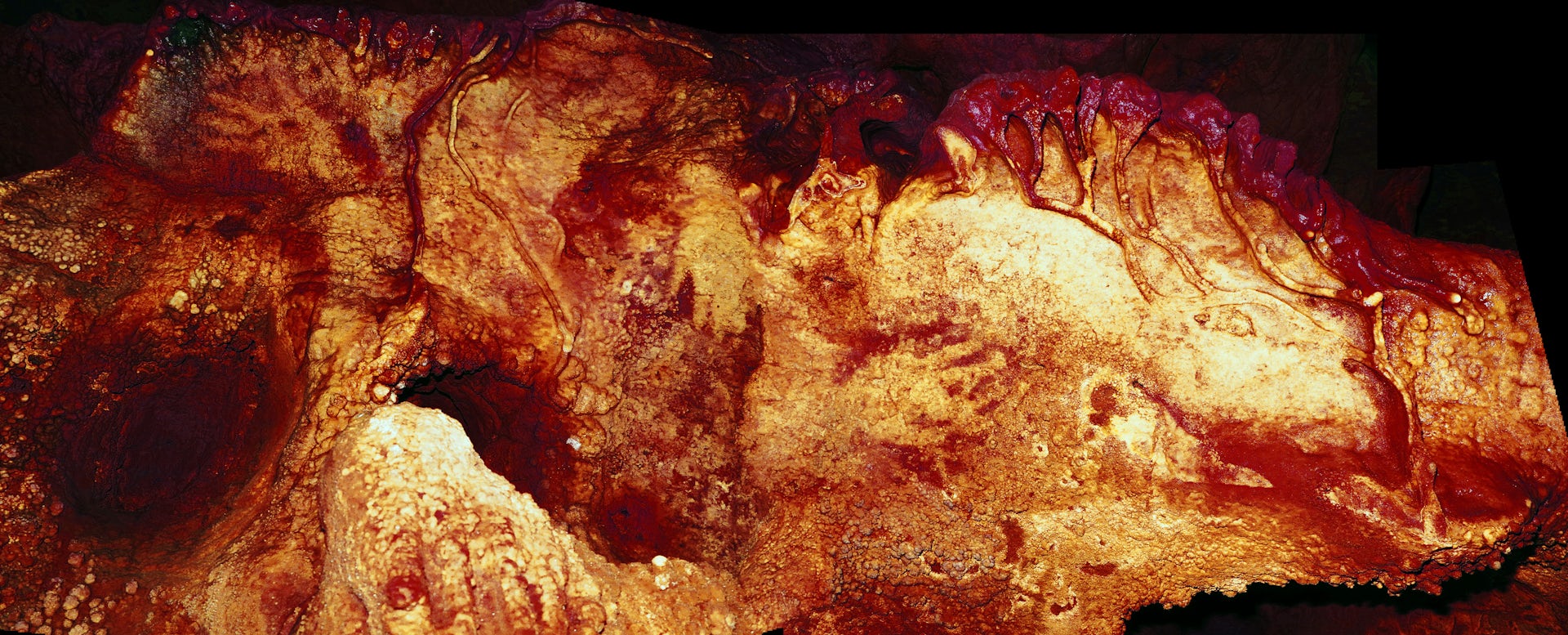

Neanderthal art.

Credit: P. Saura

Chris Standish, University of Southampton and Alistair Pike, University of Southampton

What makes us human? A lot of people would argue it is the ability of our species to engage in complex behaviour such as using language, creating art and being moral. But when and how did we first become “human” in this sense? While skeletal remains can reveal when our ancestors first became “anatomically modern”, it is much harder for scientists to decipher when the human lineage became “behaviourally modern”.

One of the key traits of behavioural modernity is the capacity to use, interpret and respond to symbols. We know that Homo sapiens have been doing this for at least 80,000 years. But its predecessor in parts of Eurasia, the Neanderthal, a human ancestor that became extinct around 40,000 years ago, has traditionally been regarded as uncultured and behaviourally inferior. Now our new study, published in Science, has challenged this view by showing that Neanderthals were able to create cave art.

The earliest examples of symbolic behaviour in African Homo sapiens populations include the use of mineral pigments and shell beads – presumably for body adornment and expressions of identity.

However, evidence for such behaviour by other human species is far more contentious. There are some tantalising clues that Neanderthals in Europe also used body ornamentation around 40,000 to 45,000 years ago. But scientists have so far argued that this must have been inspired by the modern humans who had just arrived there – we know that humans and Neanderthals interacted and even interbred.

Wall in Maltravieso Cave showing three hand stencils (centre right, centre top and top left).

Credit: H. Collado

Dating cave art

Unfortunately, we have a poor understanding of the origins of cave art, primarily due to difficulties in accurately dating it. Archaeologists typically rely on radiocarbon dating when trying to date events from our past, but this requires the sample to contain organic material.

Calcium carbonate crust overlying pigment in La Pasiega.

Credit: J. Zilhão

Uranium-thorium dating of carbonate minerals is often a better option. This well-established geochronological technique measures the natural decay of trace amounts of uranium to date the mineralisation of recent geological formations such as stalagmites and stalactites – collectively known as “speleothems”. Tiny speleothem formations are often found on top of cave paintings, making it possible to use this technique to constrain the age of cave art without impacting on the art itself.

A new era

We used uranium-thorium dating to investigate cave art from three previously discovered sites in Spain. In La Pasiega, northern Spain, we showed that a red linear motif is older than 64,800 years. In Ardales, southern Spain, various red painted stalagmite formations date to different episodes of painting, including one between 45,300 and 48,700 years ago, and another before 65,500 years ago. In Maltravieso in western central Spain, we showed a red hand stencil is older than 66,700 years.

Ladder shape in red painted in the La Pasiega cave.

Credit: C.D Standish, A.W.G. Pike and D.L. Hoffmann

Drawing of the ladder symbol painted on the walls.

Credit: Breuil et al. (1913)

Our results are tremendously significant, both for our understanding of Neanderthals and for the emergence of behavioural complexity in the human lineage. Neanderthals undoubtedly had the capacity for symbolic behaviour, much like contemporaneous modern human populations residing in Africa.

To understand how behavioural modernity arose, we now need to shift our focus back to periods when Homo sapiens and Neanderthals interacted and to the period of their last common ancestor. The most likely candidate for this ancestor is Homo heidelbergensis, which lived over half a million years ago.

It is perhaps also now time that we move beyond a focus on what makes Homo sapiens and Neanderthals different. Modern humans may have “replaced” Neanderthals, but it is becoming increasingly clear that Neanderthals had similar cognitive and behavioural abilities – they were, in fact, equally “human”.

Chris Standish, Postdoctoral Fellow of Archaeology, University of Southampton and Alistair Pike, Professor of Archaeological Sciences, University of Southampton

Religious Superstition News - Continuing Widespread Belief in Witchcraft

Witchcraft beliefs around the world: An exploratory analysis | PLOS ONE

The belief that certain individuals, often as the result of possession by demons, have the power to suspend the laws of nature at will and make unnatural events occur, sometimes with the casting of magic spells but often with a look, still persists even in some technologically advanced economies.

The belief that certain individuals, often as the result of possession by demons, have the power to suspend the laws of nature at will and make unnatural events occur, sometimes with the casting of magic spells but often with a look, still persists even in some technologically advanced economies.

This is revealed in a database, newly-compiled by Boris Gershman, associate professor of economics, American University in Washington DC, USA, and published today in the journal PLOS ONE.

Belief in witchcraft, demons and the power of magic words and/or thoughts to control natural objects and forces is just another manifestation of the teleological thinking of childhood which causes Creationism, and to some extent, religion when retained in an adult. It is based on the assumption that everything, including atoms, molecules and forces such as gravity have a personality and are sentient, so can be controlled by words and telepathically by thoughts ,and that there is a magical entity 'somewhere out there' who is controlling everything telepathically, or making laws which force them to comply.

There is, of course, no evidence to support that notion which has been part of human culture since the fearful infancy of our species, when a belief in evil magic seems a rational explanation for diseases that are now known to be caused by poisons, parasitic organisms, genetics, physiological disorders, dietary deficiencies or surfeits, etc - explanations which don't require magic and supernatural forces.

A map showing country-level prevalence of witchcraft beliefs around the world.

Boris Gershman, 2022, PLOS ONE, (CC-BY 4.0)

This is revealed in a database, newly-compiled by Boris Gershman, associate professor of economics, American University in Washington DC, USA, and published today in the journal PLOS ONE.

Belief in witchcraft, demons and the power of magic words and/or thoughts to control natural objects and forces is just another manifestation of the teleological thinking of childhood which causes Creationism, and to some extent, religion when retained in an adult. It is based on the assumption that everything, including atoms, molecules and forces such as gravity have a personality and are sentient, so can be controlled by words and telepathically by thoughts ,and that there is a magical entity 'somewhere out there' who is controlling everything telepathically, or making laws which force them to comply.

There is, of course, no evidence to support that notion which has been part of human culture since the fearful infancy of our species, when a belief in evil magic seems a rational explanation for diseases that are now known to be caused by poisons, parasitic organisms, genetics, physiological disorders, dietary deficiencies or surfeits, etc - explanations which don't require magic and supernatural forces.

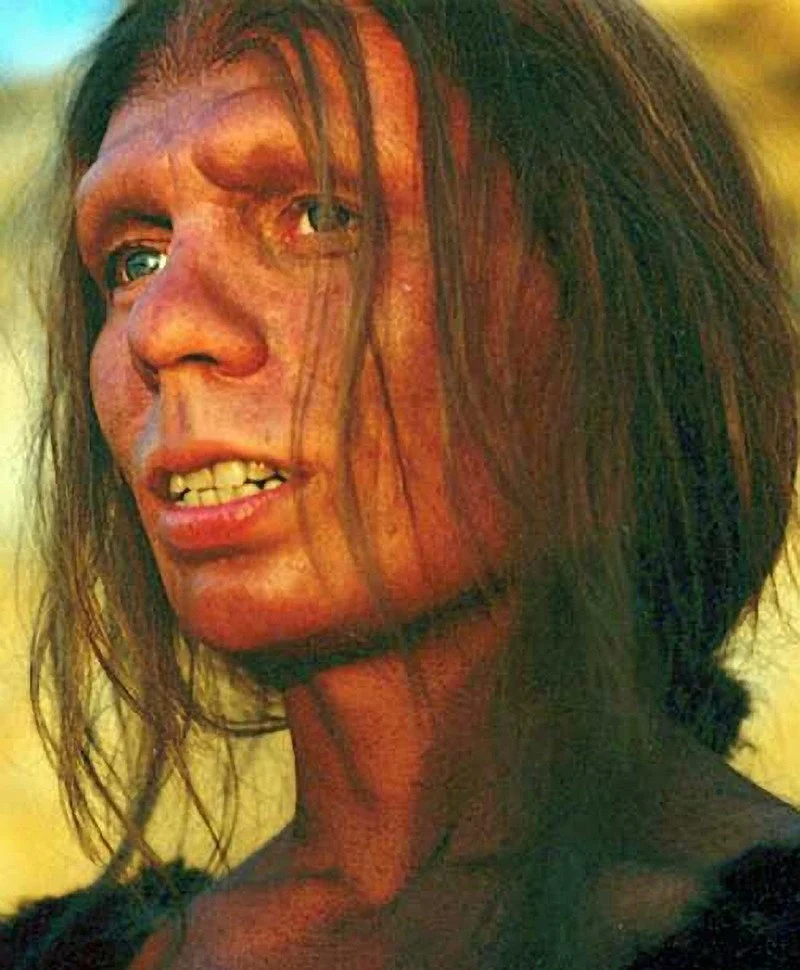

Creationism in Crisis - What if Neanderthals Had Won?

Neanderthal Woman

Artist: Tom Björklund, Moesgård Museum

8 billion people: how different the world would look if Neanderthals had prevailed

In the third of this series of articles reprinted from The Conversation, dealing with the recent evolutionary history of modern humans, Professor Penny Spikins, Professor of the Archaeology of Human Origins, University of York, UK, poses the question of how different the world would look today had the Neanderthals prevailed and not gone extinct, or, as more recent research suggests, been absorbed into the increasing and expanding population of Homo sapiens as they moved into the territory formerly occupied by Neanderthals.

An intriguing thought from this article is that humans, by forming large, urbanised groups, effectively domesticated themselves and so acquired some of the attributes of domestication that we see in, for example, domestic cattle, who now live in far larger, and more tolerant groups than their wild ancestors who lived in small groups where each individual could have a wide 'personal space'. Tolerance for others, the key to successful human groups, thus may have been a consequence as well as a cause of the formation of large human groups.

Because of the nature of their societies, where small, isolated extended family groups, separated from other bands by considerable distances, Neanderthals never self-domesticated, so never developed the mutual tolerance needed to form large, cooperative groups of unrelated individuals. In addition to their lack of genetic diversity within the group, this may have played a part in their eventual demise/absorption.

Professor Spikins' article has been reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here:

Tuesday, 22 November 2022

Covidiot News - More Evidence of the Efficacy of COVID Vaccines

Hakan Nural, Unsplash (CC0)

A new study published today on the open access journal, PLOS Medication, shows that even those people who had previously been infected with COVID-19 still benefit from vaccination, although the benefit varies a little with the batch used. The study, led by Katrine Finderup Nielsen at Statens Serum Institut, Denmark, shows that these individuals gain between 60% and 94% protection against reinfection.

According to information released by PLoS ahead of publication:

During the recent pandemic, vaccination has been one of the best tools available for curbing the spread of COVID-19. People infected with the virus are known to develop long-lasting natural immunity, but Finderup Nielsen and her team wanted to know whether these individuals would still benefit from receiving the vaccine. The team analyzed infection and vaccination data from nationwide Danish registers that included all people living in Denmark who tested positive for the virus or were vaccinated between January 2020 and January 2022. The data set included more than 200,000 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during each of the Alpha, Delta and Omicron waves. Their analysis showed that for people with previous infections, vaccination offered up to 71% protection against reinfection during the Alpha period, 94% during the Delta period and 60% during the Omicron period, with protection lasting up to nine months.

Creationism in Crisis - Six Reasons to Revise Our Thinking About Human Evolution

Six recent discoveries that have changed how we think about human origins

A point I've made before is that human evolution is far more complex than was once thought and the more fossilised remains we find, the more confusing the picture becomes. We now know, for example, that there was not a single species from which all modern humans have descended, but we are the result of multiple instances of hybridization and ingression of genes from sister and cousin species, both early on in Africa and later when Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa into Eurasi and came into contect with the descndants of earlier migrations.

The problem is that the earlier, simplistic view, of a lineal progression, superficially implies an anthropocentric, goal-oriented process, with humans at the pinacle, as the supreme achielvemtn of evolution. Essentially, replacing a religious view with a speudo-scientific one.

Although this view has been rejected by thinking people for years now, it still conditions our view of our place in the world, as owners or guardians' of it, with it all being here for our convenience. This arrogant anthropcentism has led us to where we are today, on the point of creating an uninhabitable earth with nowhere else to live. In 2015, the view that God intervened to ensure Humans evolved was still held by 24% of American adults, according to a Pew Research survey. Although Creationism is now declining in the USA, this 'God-driven' view is still held by a signifcant proportion of American adults.

The following article by Professor Penny Spikins, Professor of the Archaeology of Human Origins, University of York, UK, the second in this series of articles reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence, discussed the six recent discoveries that have caused us to change out views about our origins, not, as Creationists might home, because the Theory of evolution is wrong, but because the result of it is not the simple, linear progression we had expected it to be.

The article has been reformatted for stylistic consistence. The original can be read here:

Homo longi.

One 21 known species of humans, or is this a Denisovan?

One 21 known species of humans, or is this a Denisovan?

Chuang Zhao, Source: New Scientist

A point I've made before is that human evolution is far more complex than was once thought and the more fossilised remains we find, the more confusing the picture becomes. We now know, for example, that there was not a single species from which all modern humans have descended, but we are the result of multiple instances of hybridization and ingression of genes from sister and cousin species, both early on in Africa and later when Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa into Eurasi and came into contect with the descndants of earlier migrations.

The problem is that the earlier, simplistic view, of a lineal progression, superficially implies an anthropocentric, goal-oriented process, with humans at the pinacle, as the supreme achielvemtn of evolution. Essentially, replacing a religious view with a speudo-scientific one.

Although this view has been rejected by thinking people for years now, it still conditions our view of our place in the world, as owners or guardians' of it, with it all being here for our convenience. This arrogant anthropcentism has led us to where we are today, on the point of creating an uninhabitable earth with nowhere else to live. In 2015, the view that God intervened to ensure Humans evolved was still held by 24% of American adults, according to a Pew Research survey. Although Creationism is now declining in the USA, this 'God-driven' view is still held by a signifcant proportion of American adults.

The following article by Professor Penny Spikins, Professor of the Archaeology of Human Origins, University of York, UK, the second in this series of articles reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence, discussed the six recent discoveries that have caused us to change out views about our origins, not, as Creationists might home, because the Theory of evolution is wrong, but because the result of it is not the simple, linear progression we had expected it to be.

The article has been reformatted for stylistic consistence. The original can be read here:

Creationism in Crisis - How Evolution Resulted in 8 Billion Humans

8 billion people: how evolution made it happen

This is the first of three blog posts dealing with human evolution, reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence and reformatted for stylistic consistency.

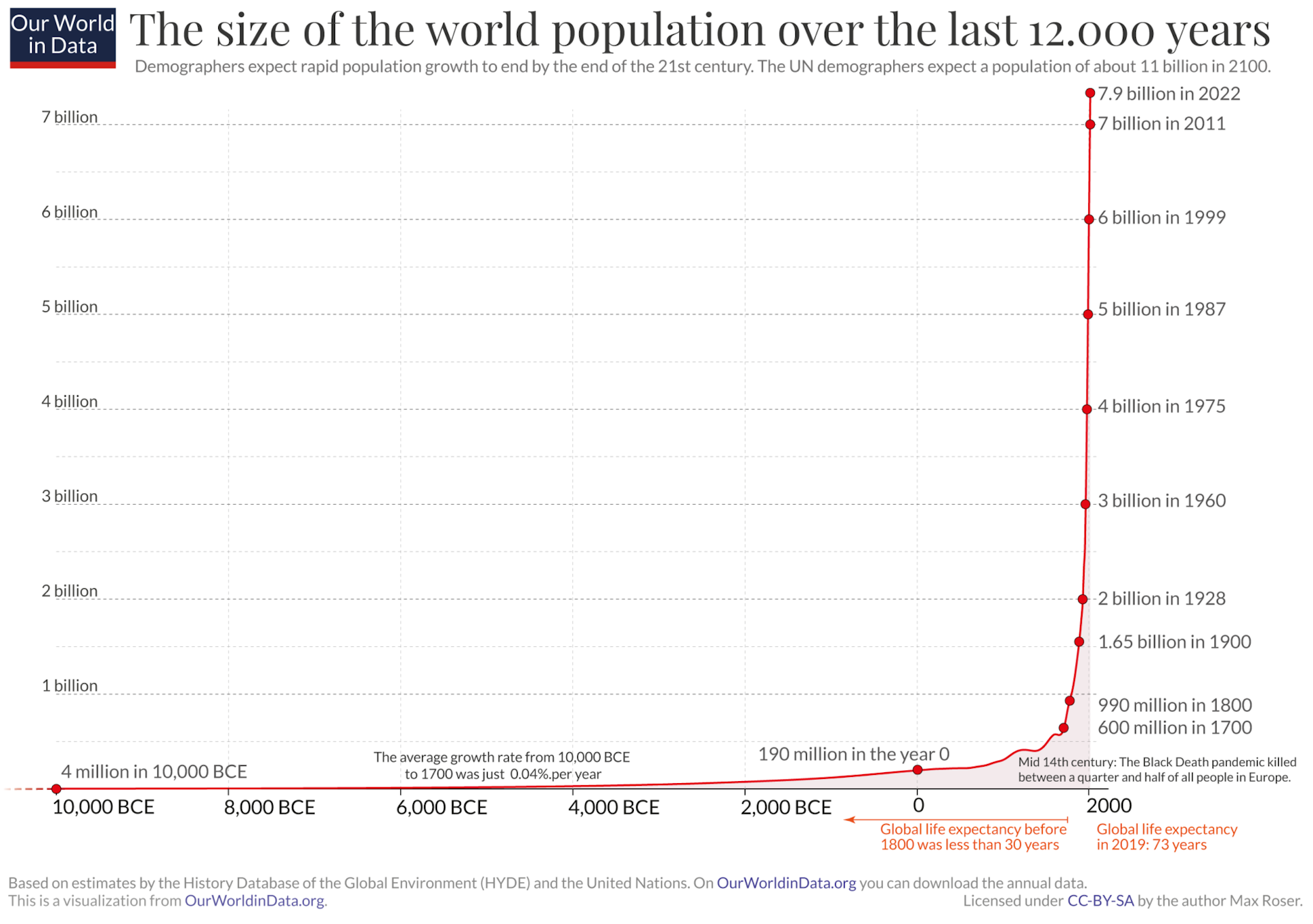

A few days ago, sometime during November 15th 2022, the human population of Earth exceeded 8 billion. In the following article by Professor Matthew Wills, Professor of Evolutionary Palaeobiology at the Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, UK, explains how our large brains and complex social structures allowed this to happen.

Cultural or memetic evolution is of course closely analogous to genetic evolution, so human evolution can be seen as the result of gene-meme co-evolution, with cooperation and the evolution of social ethics being an important part of our success, enabling us to create organised urban societies and nation states having evolved sets of ethics in common.

Professor Wills' original article can be read here:

Matthew Wills, University of Bath

November 15 2022 marks a milestone for our species, as the global population hits 8 billion. Just 70 years ago, within a human lifetime, there were only 2.5 billion of us. In AD1, fewer than one-third of a billion. So how have we been so successful?

Humans are not especially fast, strong or agile. Our senses are rather poor, even in comparison to domestic livestock and pets. Instead, large brains and the complex social structures they underpin are the secrets of our success. They have allowed us to change the rules of the evolutionary game that governs the fate of most species, enabling us to shape the environment in our favour.

But there have been many unintended consequences, and now we have raised the stakes so high that human-driven climate change has put millions of species at risk of extinction.

Understanding population growth

Understanding population growth

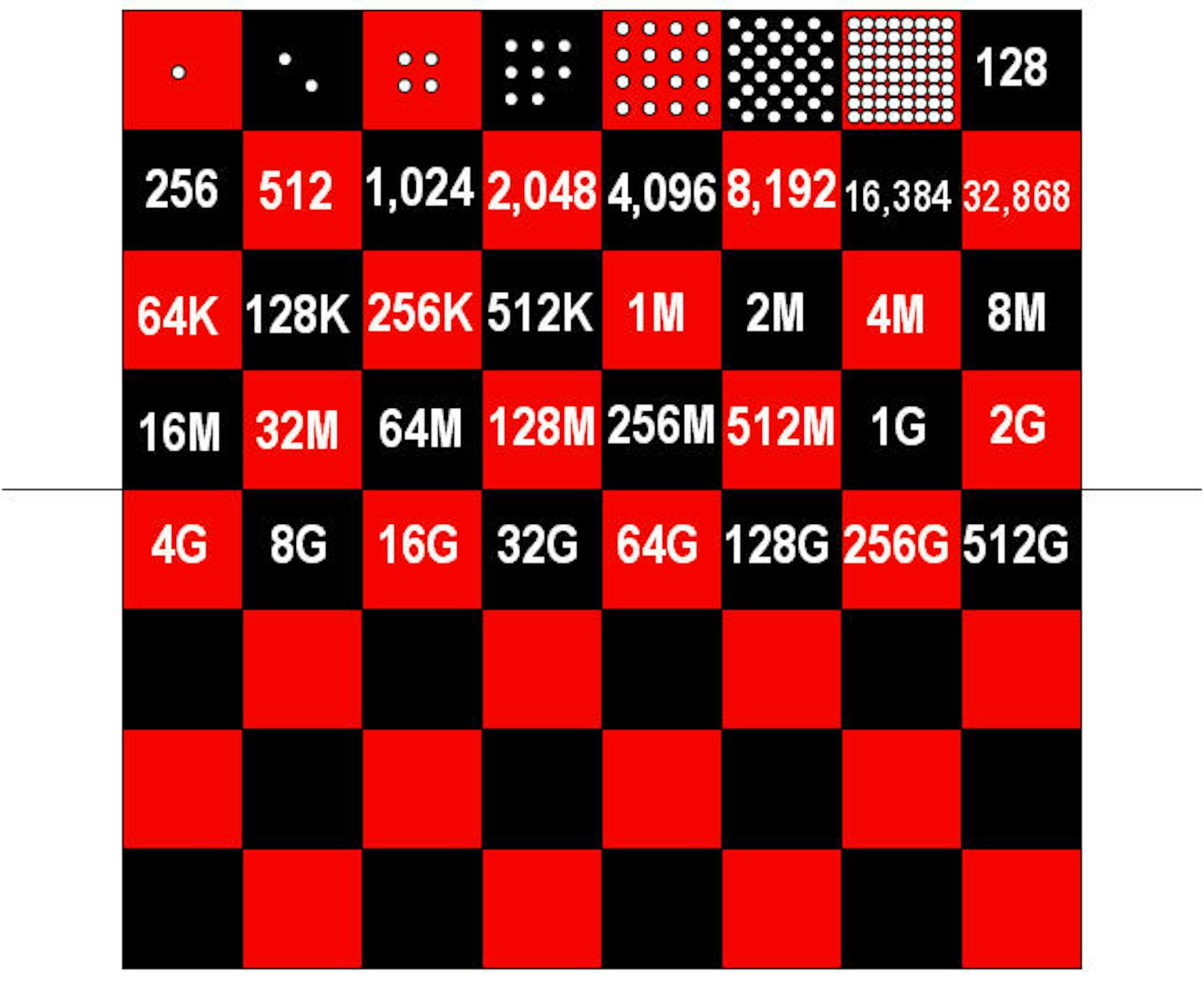

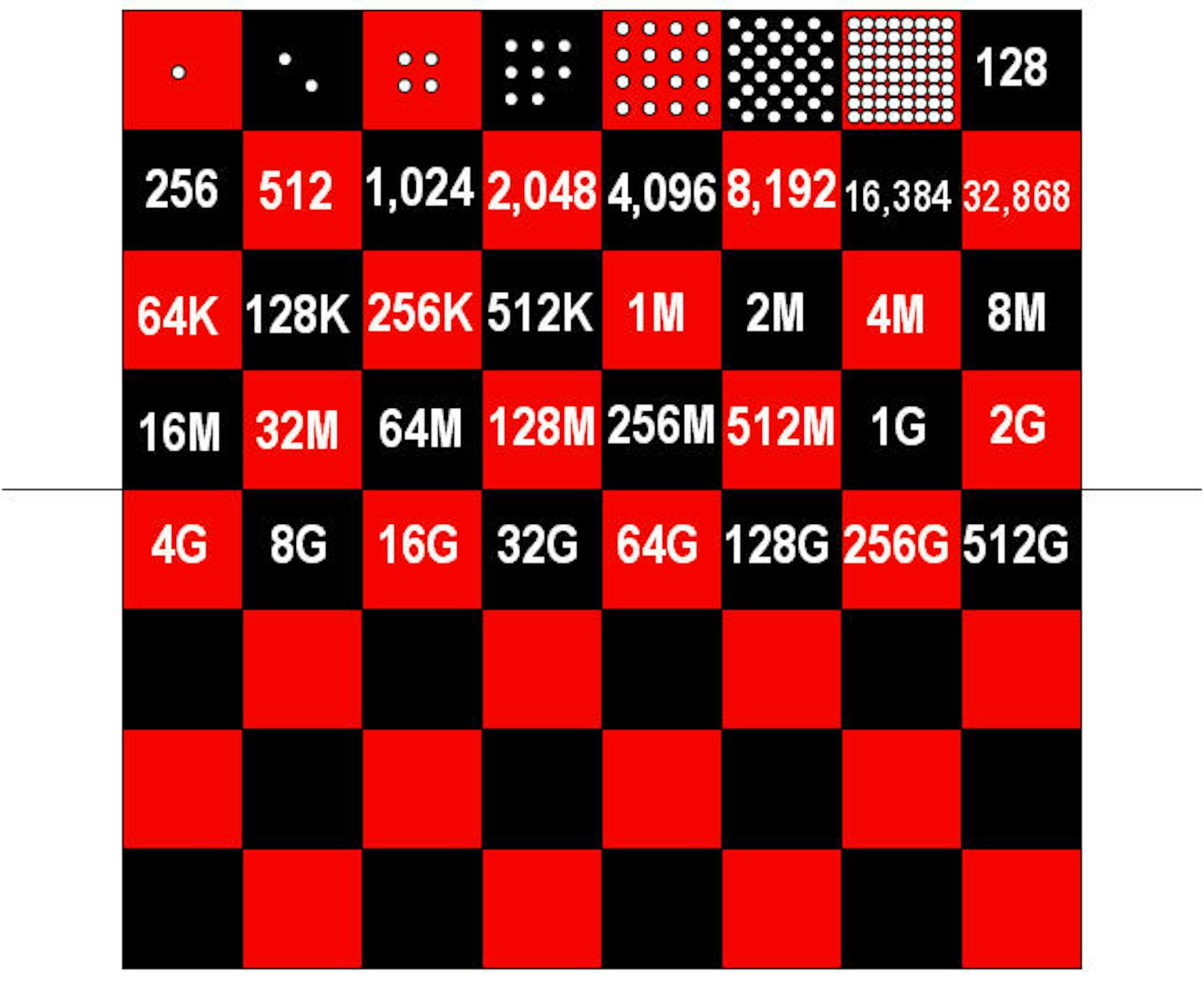

Legend has it the king of Chemakasherri, which is in modern day India, loved to play chess and challenged a travelling priest to a game. The king asked him what prize he would like if he won. The priest only wanted some rice. But this rice had to be counted in a precise way, with a single grain on the first square of the board, two on the second, four on the third, and so on. This seemed reasonable, and the wager was set.

When the king lost, he told his servants to reward his guest as agreed. The first row of eight squares held 255 grains, but by the end of the third row, there were over 16.7 million grains. The king offered any other prize instead: even half his kingdom. To reach the last square he would need 18 quintillion grains of rice. That’s about 210 billion tonnes.

When the king lost, he told his servants to reward his guest as agreed. The first row of eight squares held 255 grains, but by the end of the third row, there were over 16.7 million grains. The king offered any other prize instead: even half his kingdom. To reach the last square he would need 18 quintillion grains of rice. That’s about 210 billion tonnes.

The king learned about exponential growth the hard way.

In the beginning

Our genus – Homo – had modest beginnings at square one around 2.3 million years ago. We originated in tiny, fragmented populations along the east African rift valley. Genetic and fossil evidence suggests Homo sapiens and our cousins the Neanderthals evolved from a common ancestor, possibly Homo heidelbergensis . Homo heidelbergensis had a brain slightly smaller than modern humans. Neanderthals had larger brains than us, but the regions devoted to thinking and social interactions were less well developed.

When Homo heidelbergensis started travelling more widely, populations started to change from one another. The African lineage led to Homo sapiens, while migration into Europe around 500,000 years ago created the Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Scientists debate the extent to which later migrations of Homo sapiens out of Africa (between 200,000 and 60,000 years ago) displaced the Neanderthals or interbred with them. Modern humans who live outside Africa typically have around 2% Neanderthal DNA. It is close to zero in people from African backgrounds.

If unchecked, all populations with more births than deaths grow exponentially. Our population does not double in each generation because the average number of children per couple is fewer than four. However, the pace of growth has been accelerating at an unprecedented rate. Those of us alive today are 7% of all the humans who ever existed since the origin of our species.

Why aren’t all species booming?

Biological intervention normally puts the brakes on population growth. Predator populations increase as their prey becomes more abundant, keeping numbers in check. Viruses and other disease agents sweep through populations and decimate them. Habitats become overcrowded. Or rapidly changing environments can turn the tables on once successful species and groups.

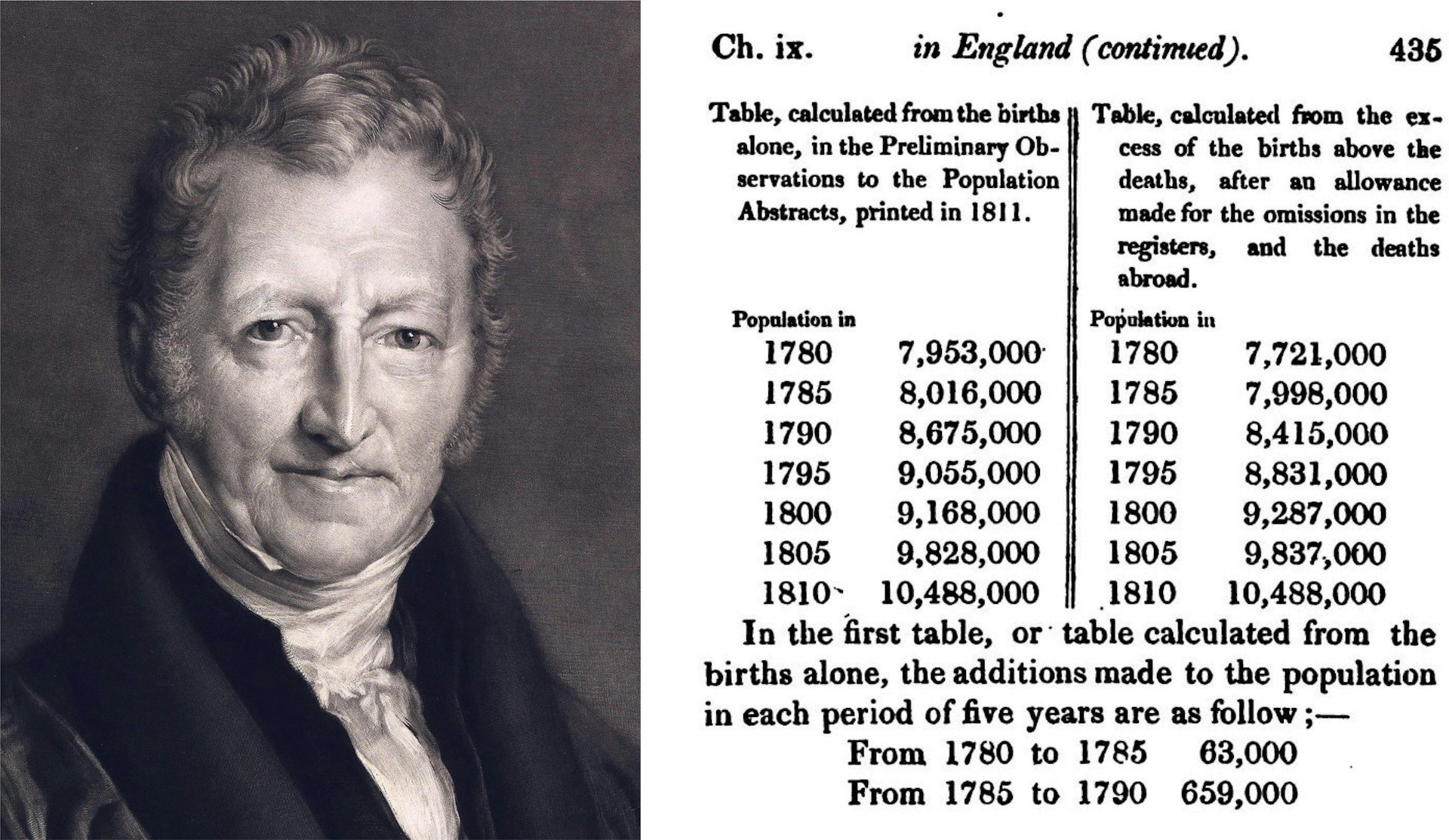

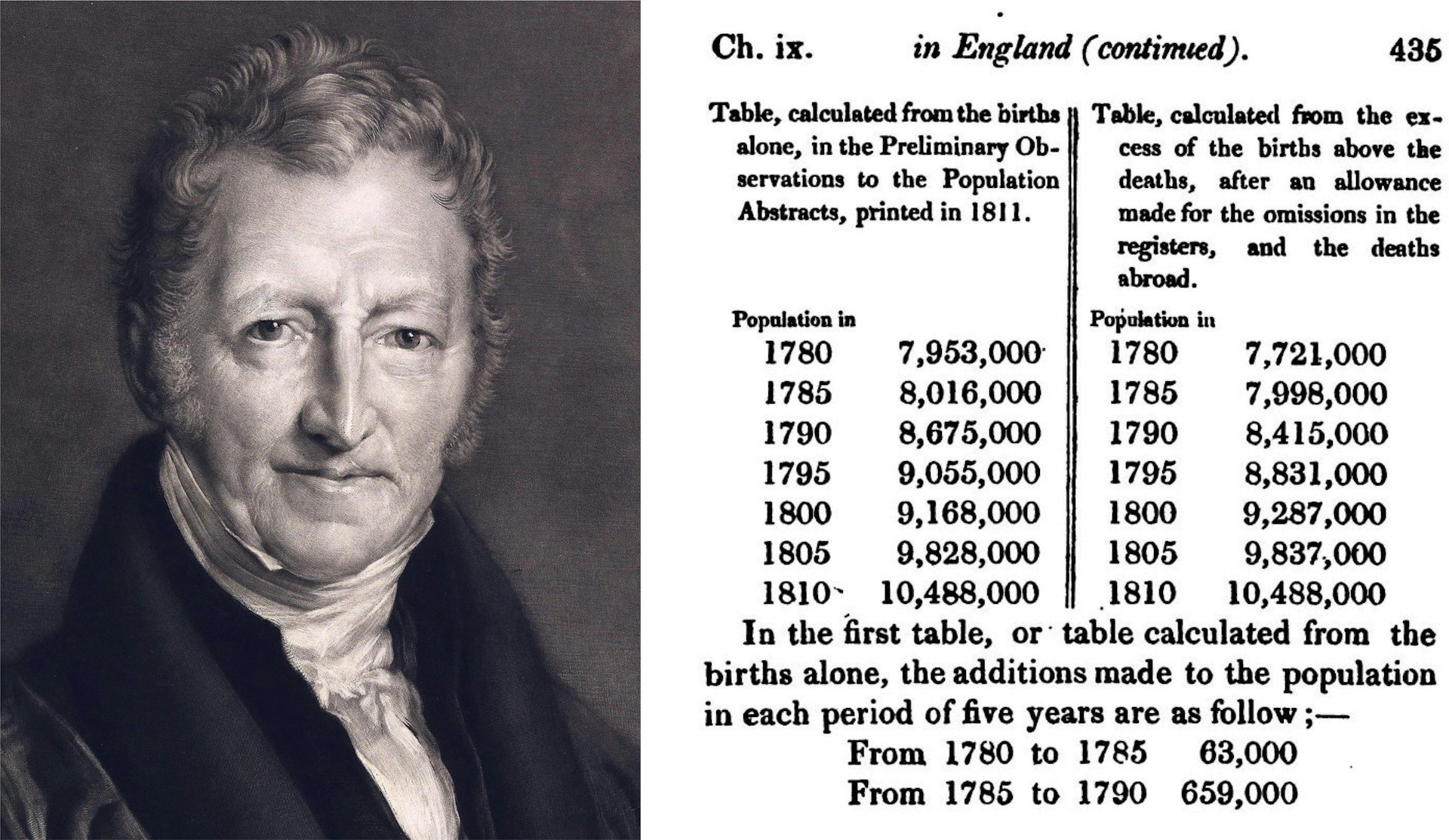

Charles Darwin, like the 18th-century scholar Thomas Malthus before him, thought there might be a hard limit on human numbers. Malthus believed our growing population would eventually outpace our ability to produce food, leading to mass starvation. But he did not foresee 19th and 20th-century revolutions in agriculture and transport, or 21st-century advances in genetic technology that allowed us to keep making more food, however patchily, across the globe.

Charles Darwin, like the 18th-century scholar Thomas Malthus before him, thought there might be a hard limit on human numbers. Malthus believed our growing population would eventually outpace our ability to produce food, leading to mass starvation. But he did not foresee 19th and 20th-century revolutions in agriculture and transport, or 21st-century advances in genetic technology that allowed us to keep making more food, however patchily, across the globe.

Our intelligence and ability to make tools and develop technologies helped us survive most of the threats our ancestors faced. Within about 8,500 years humans went from the first metal tools to AI and space exploration.

The catch

We are now kicking an increasingly heavy can down the road. The UN estimates that by 2050 there will be nearly 10 billion of us. One consequence of these vast numbers is that small changes in our behaviour can have huge effects on climate and habitats across the globe. The rising energy demands of each person today are on average twice what they were in 1900.

But what of our cousins, the Neanderthals? It turns out, in one sense, their fate was less dire than we might suppose. One measure of evolutionary success is the number of copies of your DNA that are dispersed. By this measure Neanderthals are more successful today than ever. When Neanderthal populations were last distinct from Homo sapiens (around 40,000 years ago) there were fewer than 150,000 of them. Even assuming a conservative average of 1% Neanderthal DNA in modern humans, there is at least 500 times as much in circulation today than at the time of their “extinction”.

Matthew Wills, Professor of Evolutionary Palaeobiology at the Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath

Matthew Wills, Professor of Evolutionary Palaeobiology at the Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath

This is the first of three blog posts dealing with human evolution, reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence and reformatted for stylistic consistency.

A few days ago, sometime during November 15th 2022, the human population of Earth exceeded 8 billion. In the following article by Professor Matthew Wills, Professor of Evolutionary Palaeobiology at the Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, UK, explains how our large brains and complex social structures allowed this to happen.

Cultural or memetic evolution is of course closely analogous to genetic evolution, so human evolution can be seen as the result of gene-meme co-evolution, with cooperation and the evolution of social ethics being an important part of our success, enabling us to create organised urban societies and nation states having evolved sets of ethics in common.

Professor Wills' original article can be read here:

8 billion people: how evolution made it happen

One in 8 billion.

Credit: oneinchpunch/Shutterstock

Matthew Wills, University of Bath

November 15 2022 marks a milestone for our species, as the global population hits 8 billion. Just 70 years ago, within a human lifetime, there were only 2.5 billion of us. In AD1, fewer than one-third of a billion. So how have we been so successful?

Humans are not especially fast, strong or agile. Our senses are rather poor, even in comparison to domestic livestock and pets. Instead, large brains and the complex social structures they underpin are the secrets of our success. They have allowed us to change the rules of the evolutionary game that governs the fate of most species, enabling us to shape the environment in our favour.