Creationist frauds who want to convince their cult members that the Theory of Evolution is about to be replaced in mainstream science by their childish superstition, and so become the first scientific theory ever to be replaced with an evidence-free superstition involving imaginary supernatural entities, have to keep them ignorant of papers such as this one which has just been published in Communications Biology.

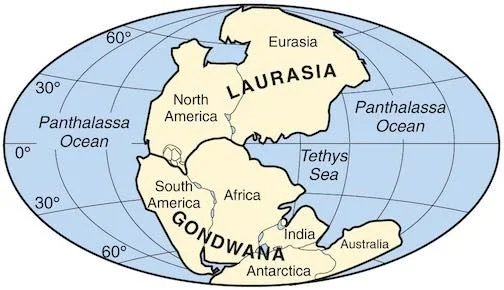

The paper, by a team of scientists led by Rosemary Prevec, a palaeontologist with Rhodes University Department of Botany, and the Department of Earth Science, Albany Museum, Makhanda, South Africa, reports on an exceptionally well preserved collection of fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids and plants - what is known to science as a 'Lagerstätte'. What's more, the formation has 'robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context', in other words, the fossils can be accurately placed in time and the changing geography of the time - some 266–268 million years ago in a river delta, when Earth had just two major landmass known as Gondwana and Laurasia, the northern and southern parts of Pangea respectively, before they were broken up and in some cases forced together by tectonic forces to form today’s major continents.

These fossils enabled the team to reconstruct the ecosystem of the time. An ecosystem is the result of interactions between species of animals and plants in a given area - the fundamental conditions for evolution to occur, as the ecosystem changes in response to internal and external pressures.

The team leader, Rosemary Prevec, has written the following article in The Conversation to explain the background to the discovery and its significance in terms of understanding the evolution of some species and the extinction of others. The Theory of Evolution is, of course, fundamental to research such as this in order to make sense of the observations. Note that nowhere does the author show the slightest doubt about the TOE's value in that understanding.

Her article is reproduced under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Find out more about The Conversation, here.

Exquisite new fossils from South Africa offer a glimpse into a thriving ecosystem 266 million years ago

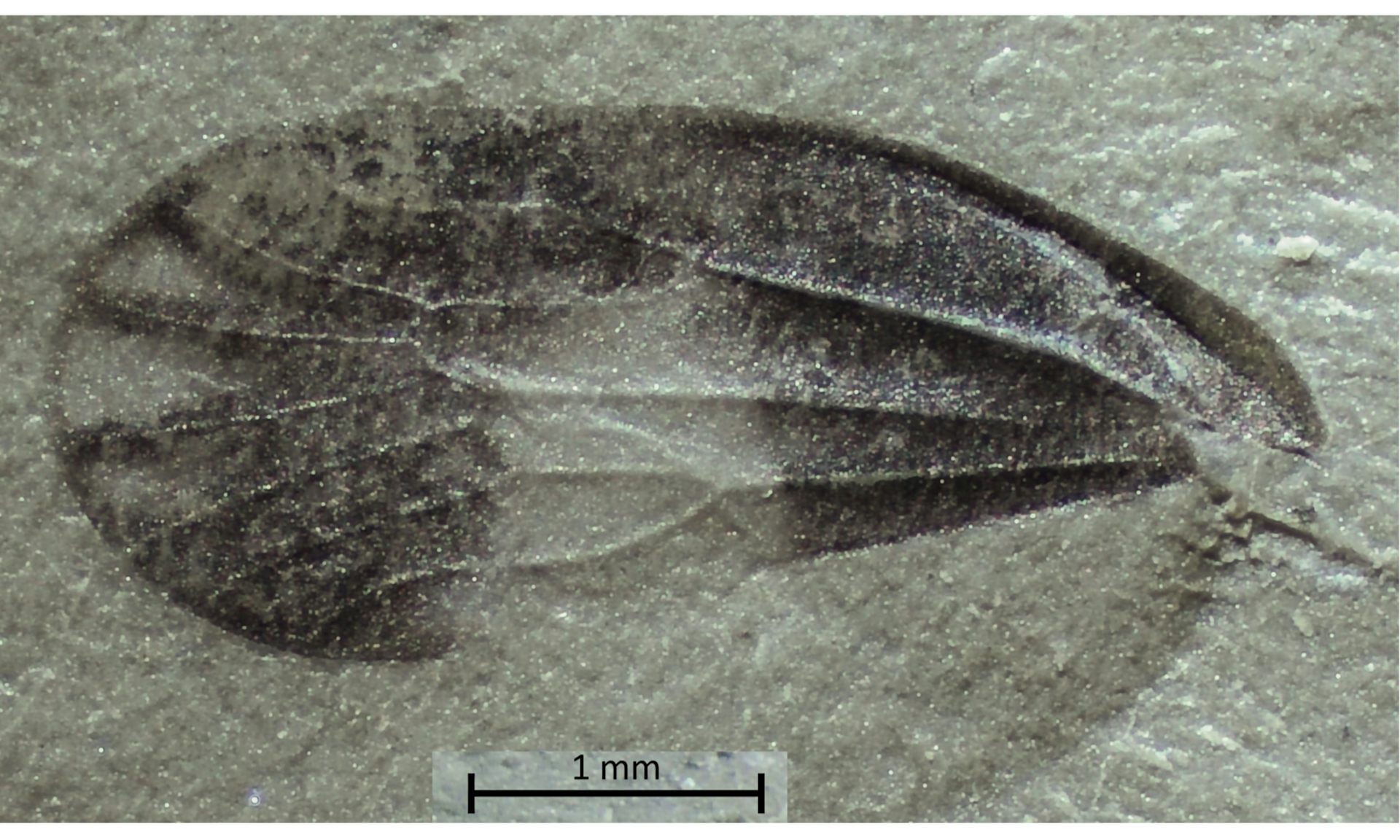

A fossilised insect wing with some of its colouration preserved is just one tiny treasure emerging from the site.

Rose Prevec

Rosemary Prevec, Rhodes University

South Africa is famous for its amazingly rich and diverse fossil record. The country’s rocks document more than 3.5 billion years of life on Earth: ancient forms of bacterial life, the emergence of life onto land, the evolution of seed-producing plants, reptiles, dinosaurs and mammals – and humanity.

Many will be familiar with hominid fossils such as the Australopithecus africanus skull Mrs (or is it Mr?) Ples and the paradigm-shifting Taung child. Less well known and equally important fossils such as the oldest terrestrial vertebrates in the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which document the first steps from the ocean and onto land, have also emerged from South Africa. The country’s wealth of fossils is due in part to the region’s unique geology, which documents 100 million years of nearly continuous deposition in its Karoo Basin.

Fossils also hold clues to climatic shifts, from the great Carboniferous ice age over 300 million years ago, to the huge dunes of blazing Jurassic deserts where dinosaurs roamed 200 million years ago. Scientists can read the devastation of the mass extinction events that destroyed global ecosystems and changed the course of Earth’s history.

But in the race to understand the “big picture” of the evolution of life and to distil its dramatic ups and downs into punchy headlines, it is easy to forget the small and quiet things. Pause, and consider what life looked like on an average day, in a world without humans, mammals, birds, butterflies, flowers, or even dinosaurs. What was it like on the shores of a rippling lake, on a drowsy summer afternoon, 266 million years ago in what’s now the Northern Cape province of South Africa?

The search, and what we found

In a new paper, my colleagues and I provide the first glimpse of such an ecosystem. We have found a profusion of fossils of tiny insects that have never been found before, as well as important plant specimens that are changing our understanding of how they evolved.

Our findings give fresh insights into the effects of extinction events on ecosystems. The subject has taken on great urgency in the face of what scientists are calling the sixth great extinction event, which is being driven by the current trend of global warming.

For the past few years we have been excavating a small, nondescript rock outcrop near Sutherland in the Northern Cape.

This outcrop is yielding untold fossil treasures of plants, insects and other invertebrates that are new to science. These unique fossils, some only a few millimetres long, are telling us about what lived in and around a calm pool on a delta plain during the middle Permian period between 266 million and 268 million years ago. Rocks of this age contain fossils of the oldest therapsids, a group of reptiles that eventually gave rise to the mammals.

Other life of this time included the lizard-like ancestors of tortoises, large amphibians that lurked like crocodiles just below the water surface, and forests dominated by a tree called Glossopteris with an understorey of spore-producing plants such as mosses, ferns and horsetails.

Teams of palaeontologists have discovered and excavated many hundreds of vertebrate fossils in the western and southern Karoo of South Africa that date back to the Permian, including the Sutherland District and surrounding areas. But the kinds of rocks that are rich in vertebrate fossil bones tend not to preserve plants and invertebrates. These seem to require the more anoxic, acidic conditions present in calm lakes and pools for high fidelity preservation, whereas bones preserve well in more oxygen-rich settings.

This makes it difficult to understand the ecosystems of this time – and means our discoveries are especially astonishing. These include the oldest freshwater leech, a record that pushes back the known range of this group by 40 million years, and the oldest water mites by 166 million years.

Other exciting finds include the oldest damsel-fly and oldest stoneflies from Gondwana, as well as a profusion of the tiny, aquatic, immature stages (nymphs) of an extinct group called the Palaeodictyoptera. Many of the insect wings we have found have yet to be identified.

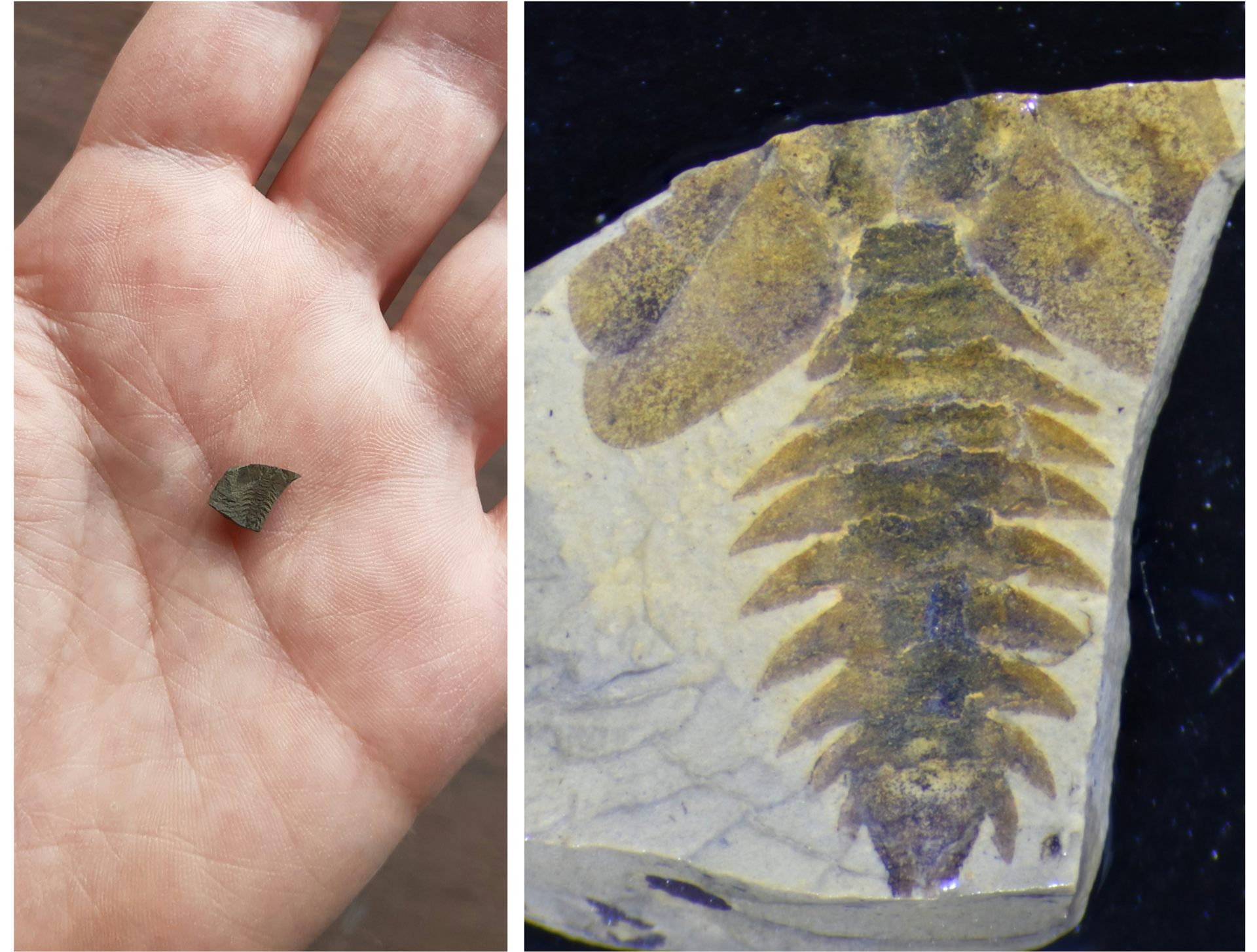

A fossil of an insect nymph - so tiny that it is dwarfed by a human hand - and, on the right, seen under a microscope.

Credit: Rose Prevec

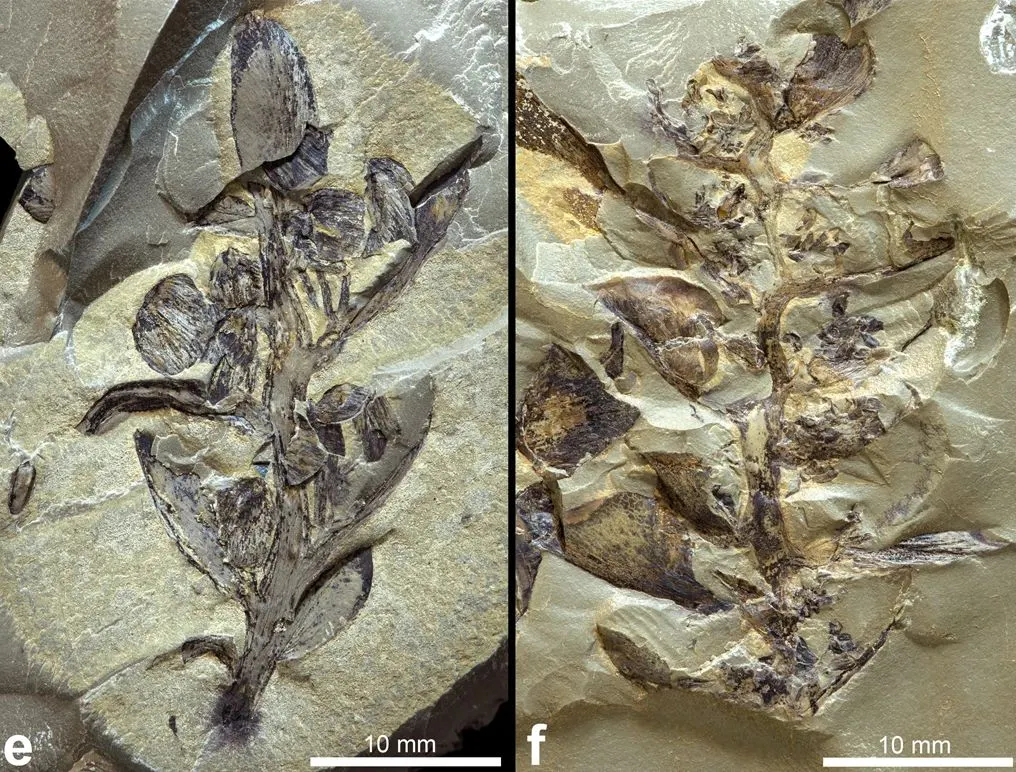

One of the most exciting finds is the dense accumulations of the male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant, an unbelievably rare occurrence that is shedding light on the evolution and classification of this important coal-forming plant.

Male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant.

Credit: Rose Prevec

Our work has been slow. Excavations have involved a lot of sitting on spiky rocks in the sun for weeks on end, extracting tiny pieces of mudrock and then examining them with a magnifying hand lens.

The fossil site is still producing new weird and wonderful plants and invertebrates, and will keep us busy for a while. There is also great potential for finding other sites in the region. The thousands of plants and insects we have collected so far are being carefully curated and studied at the Albany Museum in Makhanda. We are keenly aware of the need to conserve this precious part of South Africa’s protected natural heritage.

Our work to better understand the organisms we’re finding provides knowledge about how and when they evolved and interacted as well as about local climate, how their distributions changed through time, how the positions of the continents changed, and the effects of deserts, mountain ranges and seas on the movement and evolution of life.

This is very important when trying to understand extinction events such as the Great Dying, which marked the end of the Permian 252 million years ago. It destroyed most life in the oceans and on land and – in a chilling echo of the current global climate crisis – was driven by hundreds of thousands of years of volcanic activity that produced huge amounts of greenhouse gases, leading to an increase in global temperatures.

Rosemary Prevec, Palaeontologist, Rhodes University

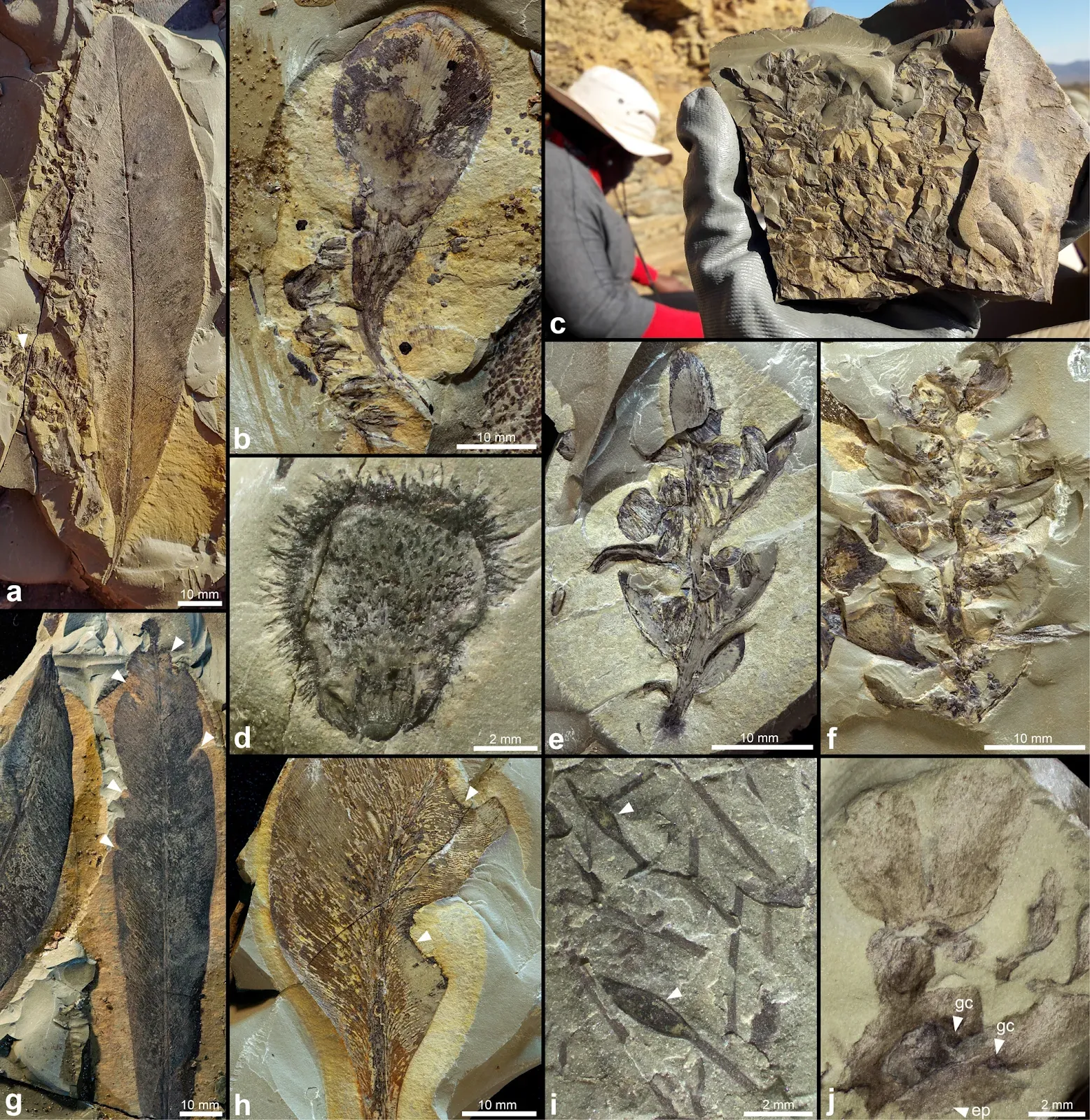

Fig. 4: Key plant fossil discoveries from the Onder Karoo locality.

a Glossopteris leaf with abundant platyspermic seeds to the left. Arrow indicates adjacent Lidgettonia sp. 1 fructification, the likely source of the seeds. b Lidgettonia sp. 1: large scale leaf with at least five pairs of cupules attached. c Slab showing mixed mat of male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant. d New dictyopteridean, seed-bearing glossopterid fructification Ottokaria. e Female cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Lidgettonia sp. 2 fertiligers attached to a shoot. f Male cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Eretmonia sp. polleniferous scales attached to a shoot. g Glossopteris leaves, arrows indicate sites of margin-feeding by insects. h Glossopteris leaf with arrows indicating large excisions caused by insect feeding, note pronounced staining of plant reaction tissue. i Probable moss sporophytes, arrows indicate moss capsules. j Thallose liverwort with dichotomous branching, notched termini, hydroids, typical epidermal patterning (ep, arrow) and possible gemma cups (gc, arrows).

a Glossopteris leaf with abundant platyspermic seeds to the left. Arrow indicates adjacent Lidgettonia sp. 1 fructification, the likely source of the seeds. b Lidgettonia sp. 1: large scale leaf with at least five pairs of cupules attached. c Slab showing mixed mat of male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant. d New dictyopteridean, seed-bearing glossopterid fructification Ottokaria. e Female cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Lidgettonia sp. 2 fertiligers attached to a shoot. f Male cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Eretmonia sp. polleniferous scales attached to a shoot. g Glossopteris leaves, arrows indicate sites of margin-feeding by insects. h Glossopteris leaf with arrows indicating large excisions caused by insect feeding, note pronounced staining of plant reaction tissue. i Probable moss sporophytes, arrows indicate moss capsules. j Thallose liverwort with dichotomous branching, notched termini, hydroids, typical epidermal patterning (ep, arrow) and possible gemma cups (gc, arrows).

Fig. 5: A selection of newly discovered invertebrate fossils from the Onder Karoo locality.

a AM14859: exuviae of a nymph (Palaeodictyopterida). b AM13265: stonefly nymph (Plecoptera). c AM11348: cluster of plecopteran nymph exuviae associated with glossopterid seeds. d AM11296: distal fragment of a wing of Afrozygopteron inexpectatus45, a Protozygoptera (an early damselfly-like Odonatoptera), with sclerotized costo-apical pterostigma (arrow). e AM11389: forewing of an ‘ice crawler’, Colubrosopterum karooensis (a new genus of ‘Grylloblattodea’, Liomopteridae46). f AM14864d: two forewings of Protelytoptera. g AM14864e: two forewings of Anthracoptilidae (Paoliida). h AM14858ab: composite image of part and counterpart of a hemipteran forewing (Prosbolidae). i AM11298a: hemipteran forewing with pattern of wing colouration preserved (Scytinopteridae). j AM11157a: large forewing of a cicadamorph with pattern of colouration preserved (Hemiptera, Pereboriidae). k terrestrial nymph/nymph exuviae (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha). l annelid worm, probable Clitellata (leech) with circular sucker (arrow). m AM11282b: elytron of a beetle with punctate ornamentation (Coleoptera, Permocupedidae). n AM14856: water mite (Acari, Hydrachnidia).

a AM14859: exuviae of a nymph (Palaeodictyopterida). b AM13265: stonefly nymph (Plecoptera). c AM11348: cluster of plecopteran nymph exuviae associated with glossopterid seeds. d AM11296: distal fragment of a wing of Afrozygopteron inexpectatus45, a Protozygoptera (an early damselfly-like Odonatoptera), with sclerotized costo-apical pterostigma (arrow). e AM11389: forewing of an ‘ice crawler’, Colubrosopterum karooensis (a new genus of ‘Grylloblattodea’, Liomopteridae46). f AM14864d: two forewings of Protelytoptera. g AM14864e: two forewings of Anthracoptilidae (Paoliida). h AM14858ab: composite image of part and counterpart of a hemipteran forewing (Prosbolidae). i AM11298a: hemipteran forewing with pattern of wing colouration preserved (Scytinopteridae). j AM11157a: large forewing of a cicadamorph with pattern of colouration preserved (Hemiptera, Pereboriidae). k terrestrial nymph/nymph exuviae (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha). l annelid worm, probable Clitellata (leech) with circular sucker (arrow). m AM11282b: elytron of a beetle with punctate ornamentation (Coleoptera, Permocupedidae). n AM14856: water mite (Acari, Hydrachnidia).

More detail is given in the abstract to the team's open access paper in Communications Biology:

AbstractAnd another research paper casually refutes the Creationist lie that the TOE is being increasingly rejected by serious scientists.

Continental ecosystems of the middle Permian Period (273–259 million years ago) are poorly understood. In South Africa, the vertebrate fossil record is well documented for this time interval, but the plants and insects are virtually unknown, and are rare globally. This scarcity of data has hampered studies of the evolution and diversification of life, and has precluded detailed reconstructions and analyses of ecosystems of this critical period in Earth’s history. Here we introduce a new locality in the southern Karoo Basin that is producing exceptionally well-preserved and abundant fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids, and plants. Within a robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context, this Konservat- and Konzentrat-Lagerstätte offers a unique opportunity for the study and reconstruction of a southern Gondwanan deltaic ecosystem that thrived 266–268 million years ago, and will serve as a high-resolution ecological baseline towards a better understanding of Permian extinction events.

Prevec, R., Nel, A., Day, M.O. et al.

South African Lagerstätte reveals middle Permian Gondwanan lakeshore ecosystem in exquisite detail.

Commun Biol 5, 1154 (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-022-04132-y

Copyright: © 2022 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.