Slideshow code developed in collaboration with ChatGPT3 at https://chat.openai.com/

New DNA testing shatters 'wild dog' myth: most dingoes are pure

Recent new findings illustrate the way a species will evolve by diverging into related species that may still be able to interbreed even though other indicators show that they should be regarded as a distinct species. It also shows how a single species can diverge into populations as the precursor to evolving into subspecies and then species.

How are dingoes unique?It also shows how, as science refines and improves its techniques, new information brings about a change of consensus in a classic example of scientific opinion changing when the information changes, unlike religion which needs to find reasons not to change its collective mind despite new information, or risk another fragmentation into mutually hostile sects.

Dingoes possess several unique characteristics that distinguish them from domestic dogs and wolves. These characteristics include:It's important to note that while these characteristics are typical of dingoes, there can be variations among individuals and populations. Additionally, some of these traits may be influenced by interbreeding between dingoes and domestic dogs, which can introduce genetic diversity into the dingo population.

- Size and Body Proportions: Dingoes are typically smaller than wolves and many domestic dog breeds. They exhibit a lean and agile body structure with a head that is broader and flatter than that of domestic dogs.

- Coat Color and Texture: Dingoes commonly have a sandy or reddish-brown coat color, although variations can occur. Their coat is usually short, dense, and well-adapted to the Australian climate. Some dingoes have a white chest and facial markings.

- Cranial Features: Dingoes often have a skull shape that is different from both domestic dogs and wolves. Their skull is generally longer and less domed than that of most dogs, with a narrower zygomatic arch (cheekbone) region.

- Dentition: Dingoes possess a unique set of teeth, including relatively large canine teeth and sharp carnassial teeth adapted for cutting flesh. Compared to domestic dogs, their teeth are generally larger and exhibit less size variation.

- Behavior and Social Structure: Dingoes are highly adaptable and display behavior suited to their semi-arid and arid habitats. They are generally more independent and less social than domestic dogs. Dingoes often live in small packs or as solitary individuals, whereas wolves form larger, more structured packs.

- Reproduction and Breeding: Dingoes typically have a different breeding cycle than domestic dogs, with a once-a-year breeding season. They also exhibit different mating behaviors and have fewer puppies per litter compared to many domestic dog breeds.

ChatGPT3 "What are the unique characteristics that distinguish dingoes from domestic dogs and wolves?" [Response to user question]

Retrieved from https://chat.openai.com/

The study is a re-examination and re-evaluation of the status of the Australian dingo, Canis dingo, in view of improved DNA testing. Using earlier techniques which involved comparing just 23 DNA markers, geneticists had concluded that there were very few pure-bred dingoes left as most had DNA derived from hybridization with feral domestic dogs, Canis familiaris. On that basis, the dingo was reclassified as a wild dog and an invasive pest, and several eradication programs were implemented.

But a new study, using newer techniques which enable the scientists to compare not just 23 but 195,000 DNA markers has revealed a very different picture. This shows not only that ingression of familiaris DNA has been very limited in some areas, but that the dingo species can be regarded as four distinct populations. In other words, not only is the dingo still a species distinct from feral dogs but the dingo species is showing early signs of speciating.

It is now accepted that dingoes have not evolved directly from wolves so are not a subspecies of Canis lupus but are descended from the Southeast Asian domestic dog, meaning they were taken to Australia by humans and have evolved to adapt to the Australian environment. They have also been there so long that they have become an important part of the Australian ecosystem as apex predators, so can't now be regarded as an alien species, unlike rabbits, rats, European foxes, mice, cane toads and domestic cats.

The new study, by geneticists from the University of New South Wales and Sydney University, NSW, Australia, with colleagues in the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, is published, open access, in the journal Molecular Ecology.

Three of the scientists, Kylie M Cairns, Research fellow, UNSW Sydney, Mathew Crowther, Associate professor, University of Sydney and Professor Mike Letnic, Evolution and Ecology Research Centre, UNSW Sydney have explained their research and its significance for dingo conservation in an article in The Conversation. Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency.

New DNA testing shatters ‘wild dog’ myth: most dingoes are pure

Source: Jun Zhang, Shutterstock

Kylie M Cairns, UNSW Sydney; Mathew Crowther, University of Sydney, and Mike Letnic, UNSW Sydney

For decades, crossbreeding between dingoes and dogs has been considered the greatest threat to dingo conservation. Previous DNA studies suggested pure dingoes were virtually extinct in Victoria and New South Wales.

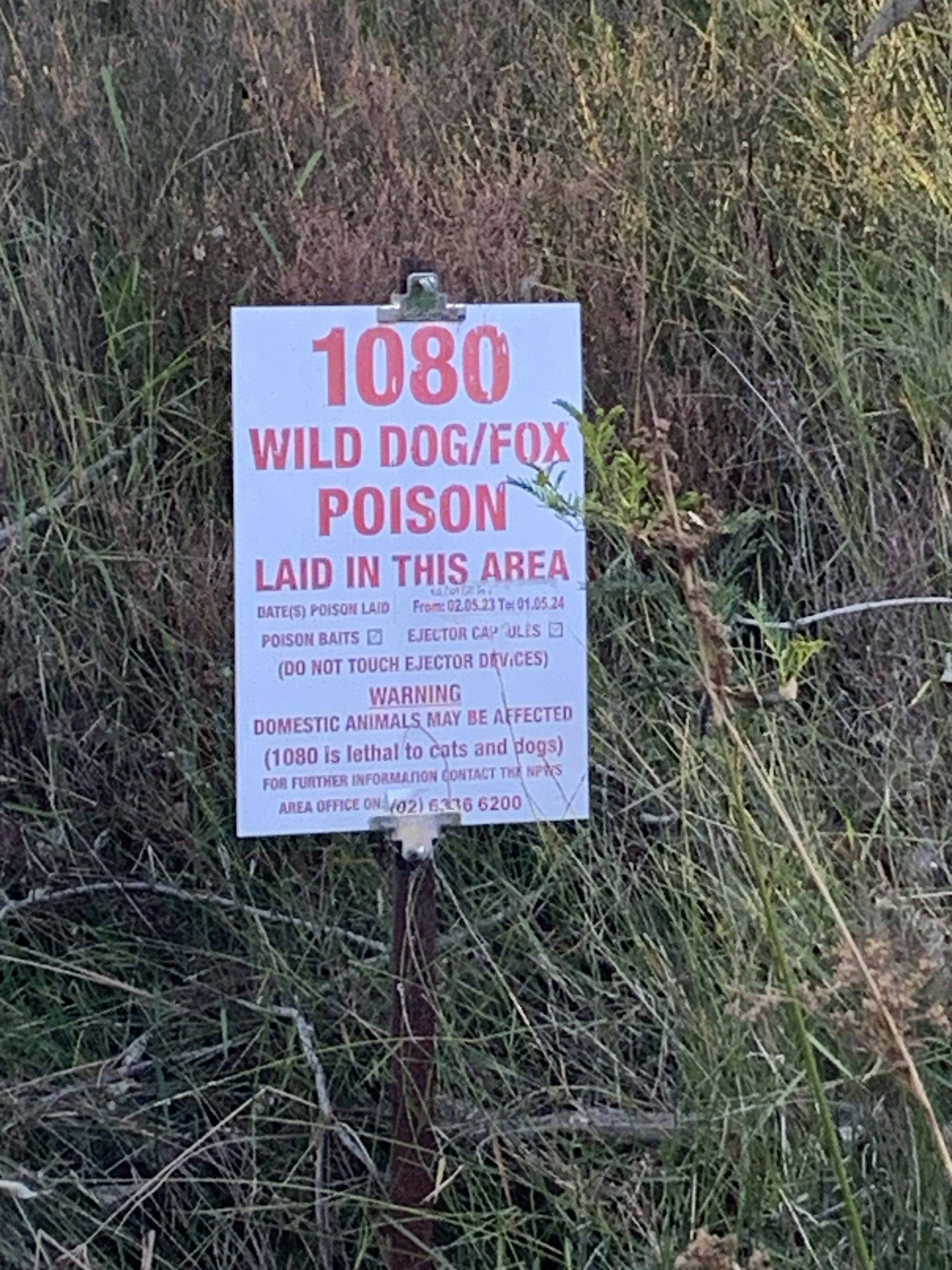

A 1080 wild dog and fox baiting sign from inside Blue Mountains National Park.

Source: Kylie Cairns

Our new research used the latest genetic testing methods to establish the ancestry of wild dogs across Australia. Most of the 307 wild animals we tested were pure dingoes. Only a small proportion of wild dingoes had dog ancestry, probably from a great- or great-great-grandparent. There were no “first-cross” (50/50) hybrids or feral dogs in our wild-caught sample.

Essentially, all the “wild dogs” were dingoes. The results challenge public perceptions and call into question well established management practices. We argue the term “wild dog” should be removed from public language and legislation. Dingo and feral dog should be used instead. And the role of the dingo as Australia’s apex predator should be restored, for we are the greatest threat to their existence.

A pure dingo from Myall Lakes walking on a sand dune.

Source: Chontelle Burns/Nouveau Rise Photography, CC BY

The dingo (Canis dingo) has been in Australia for 5,000 to 11,000 years. But while dingoes are genetically distinct from domestic dogs, they can breed with them.

Scientific support for the idea that few pure dingoes remain in eastern Australia came from skull measurement tests developed in the 1980s and a DNA test developed in the 1990s.

Applying these approaches, Victoria listed dingoes as a threatened species after finding just 1% of animals killed in pest control programs were pure dingoes. Similarly in NSW “predation and hybridisation by feral dogs (Canis familiaris)” was listed as a key threatening process in 2009.

But DNA testing methods have improved since then. When we compared old and new DNA testing methods in our study, we found the original method frequently misidentified pure dingoes as hybrids. This is because the technique used a relatively small number of DNA markers, only 23. We used 195,000 DNA markers.

A DNA marker is a genetic change that can be used to study differences between species, populations or individuals. This is the same sort of technology used for human ancestry or family tree testing. In general, more DNA markers means more information about an individual and more accurate DNA test results.

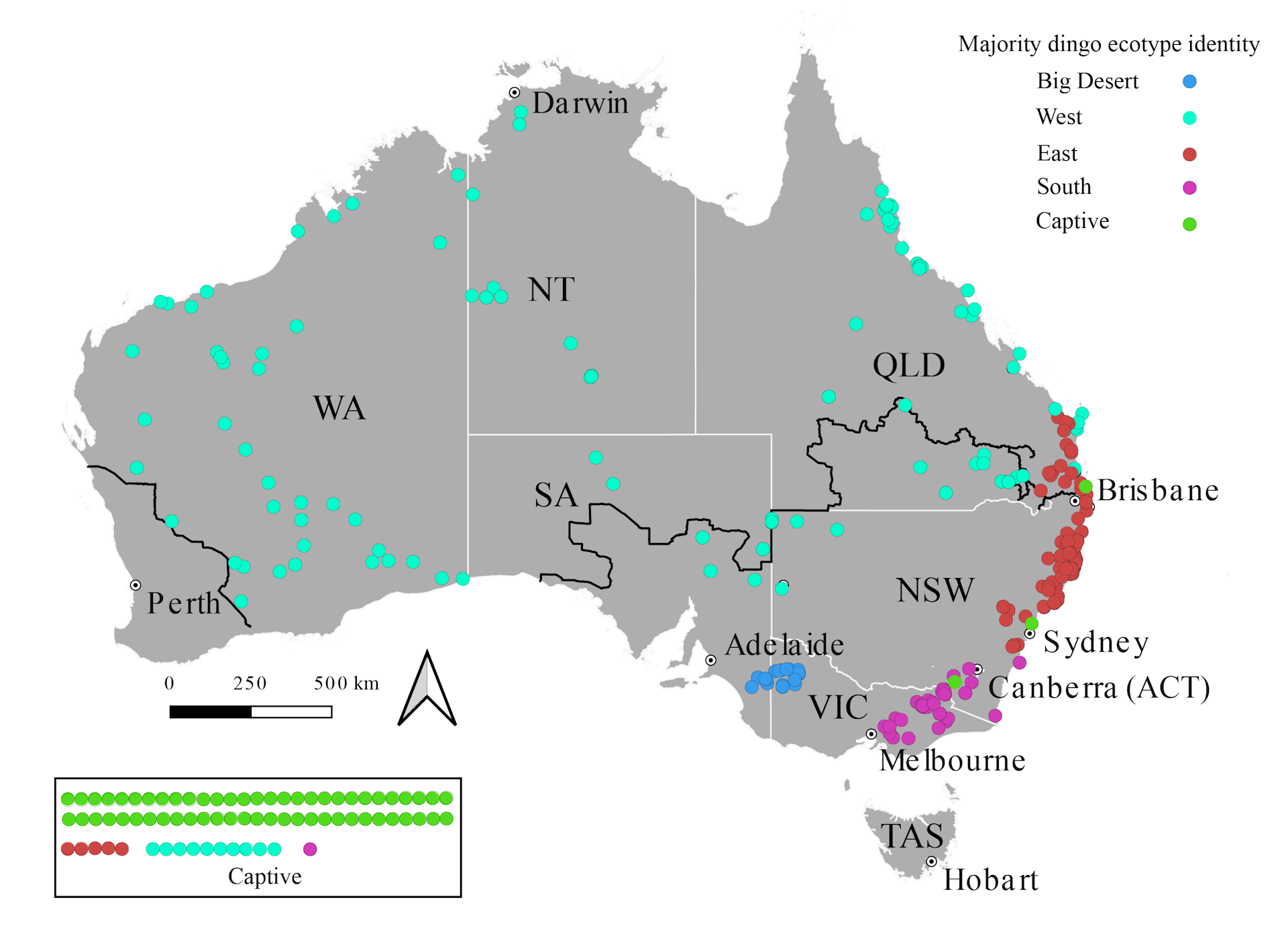

The older method was also unable to account for geographic variation in dingoes. We found evidence of at least four populations or varieties of dingo in Australia, which we call: West, East, South and Big Desert.

A map showing the distribution of the four wild dingo populations across Australia from Cairns et al. 2023.

Dog ancestry was more common in NSW and Queensland dingo populations where there were intensive lethal control programs, such as aerial 1080 poison baiting, along with higher numbers of pet domestic dogs. One explanation is that lethal control programs carried out during the dingo breeding season may increase the risk of dingo-dog hybrids, as it does for wolves and coyotes in North America. Australian aerial baiting programs can kill up to 90% of the dingoes in an area, reducing the availability of mates for any remaining dingoes.

These findings have important implications for our knowledge of dingoes and how they are managed. We need to ensure public policy is built on robust, up-to-date knowledge of dingo identity and ancestry.

Wildlife managers and scientists should ensure that the DNA testing methods they use are accurate and fit for purpose. It is crucial that updated genetic surveys be carried out on dingoes, using the latest DNA methods to inform local dingo management plans.

Dingo conservation plans should consider the presence of geographic variation and the differing threats the four dingo populations may be facing.

Currently, dingoes fall into a grey area: because they are both a native animal and agricultural pest; and because their identity has become ambiguous due to the widespread adoption of the term wild dog.

Lethal control programs have been extended into conservation areas, including national parks, with the primary purpose of minimising livestock losses on neighbouring lands.

During 2020-2021, NSW dropped more than 200,000 1080 poisoned meat-baits from planes and helicopters to suppress “wild dogs”.

This year Victoria renewed its “wild dog bounty” program. It pays landholders A$120 per wild dog body part. Under the scheme, about 4,600 “wild dog” body parts have reportedly been redeemed since 2011.

Alpine dingoes can be found at high elevations along eastern Australia.

Source: Michelle J Photography, Cooma, NSW., Author provided

Our study shows the term “wild dog” is a misnomer. The animals being targeted for eradication as an “invasive” pest are native dingoes.

The threat of dingo-dog hybrids has also been exaggerated. While dingoes can pose a threat to some livestock, as apex predators they play an essential role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. The dingo keeps natural systems in balance by preying on large herbivores and excluding invasive predators such as feral cats and foxes. This in turn benefits small marsupials, birds and reptiles. We need to balance managing dingo impacts on agriculture against ensuring they can perform their vital environmental functions.

The term “wild dog” should be removed from public language and legislation. Dingo and feral dog should be used instead. This change in terminology would accurately reflect the fact that a vast majority of the wild canines in Australia are pure dingoes – and the hybrids are predominantly dingo in their genetic make-up.

A name change would also align with calls from Australia’s First Nations people to respect and acknowledge the dingo as a native and culturally significant species.

Kylie M Cairns, Research fellow, UNSW Sydney; Mathew Crowther, Associate professor, University of Sydney, and Mike Letnic, Professor, Evolution and Ecology Research Centre, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AbstractSo, although Canis dingo has had an ingression of domestic dog DNA into its genome, this has been far less than previously thought, so it is still distinct enough to be regarded as a unique species. As such it is not an invasive species but has a key role as Australia's apex predator, the presence of which has been shaping Australian fauna for at least 5,000 years and possibly 11,000 years.

Admixture between species is a cause for concern in wildlife management. Canids are particularly vulnerable to interspecific hybridisation, and genetic admixture has shaped their evolutionary history. Microsatellite DNA testing, relying on a small number of genetic markers and geographically restricted reference populations, has identified extensive domestic dog admixture in Australian dingoes and driven conservation management policy. But there exists a concern that geographic variation in dingo genotypes could confound ancestry analyses that use a small number of genetic markers. Here, we apply genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping to a set of 402 wild and captive dingoes collected from across Australia and then carry out comparisons to domestic dogs. We then perform ancestry modelling and biogeographic analyses to characterise population structure in dingoes and investigate the extent of admixture between dingoes and dogs in different regions of the continent. We show that there are at least five distinct dingo populations across Australia. We observed limited evidence of dog admixture in wild dingoes. Our work challenges previous reports regarding the occurrence and extent of dog admixture in dingoes, as our ancestry analyses show that previous assessments severely overestimate the degree of domestic dog admixture in dingo populations, particularly in south-eastern Australia. These findings strongly support the use of genome-wide SNP genotyping as a refined method for wildlife managers and policymakers to assess and inform dingo management policy and legislation moving forwards.

Cairns, K. M., Crowther, M. S., Parker, H. G., Ostrander, E. A., & Letnic, M. (2023).

Genome-wide variant analyses reveal new patterns of admixture and population structure in Australian dingoes. Molecular Ecology, 00, 1– 18. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16998

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

A question then for Creationists: what 'kind' is the dingo, and should it be regarded as just an invasive wild dog and irradicated, or is it a unique 'kind'? If so, what is the basis for that decision?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.