Ambulator keanei (reconstruction)

Credit: Jacob D. van Zoelen, Aaron B. Camens, Trevor H. Worthy and Gavin J. Prideaux.

(CC BY 4.0)

(CC BY 4.0)

In some ways, I almost feel sorry for creationists the way science keeps refuting their beliefs, if only they weren't so arrogant as to assume that their ignorance makes them more expert than the experts and so qualified to pronounce the best-supported theory in science, wrong, for the simple, reason that they don't like it.

Well, for that reason, I have the great pleasure in pricking their pomposity and reporting the first of two more scientific papers that refute them, not that they will read them, or understand them if they do.

The second paper will be the subject of my next blog post.

This one concerns the finding that there were giant marsupials in Australia nearly 3.5 million years before creationists believe Earth was created by magic out of nothing.

This comes in the form of an open access paper by four Australian scientists, published in the Royal Society Open Science journal, three of whom, Jacob van Zoelen, PhD Candidate, Aaron Camens, Lecturer in Palaeontology, and Professor Gavin Prideaux, all of Flinders University, have written about their research in The Conversation. Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Newly described enormous marsupial wandered great distances across Australia 3.5 million years ago

Jacob van Zoelen, Author provided

Jacob van Zoelen, Flinders University; Aaron Camens, Flinders University, and Gavin Prideaux, Flinders University

Today, 80% of Australia is arid, but it was not always that way. In the early Pliocene, 5.4 to 3.6 million years ago, Australia had a greenhouse climate, widespread forests and diverse marsupial animals.

As the climate dried out in the late Pliocene, open woodland, grassland and shrubland spread across Australia. How did large marsupials cope with these changes?

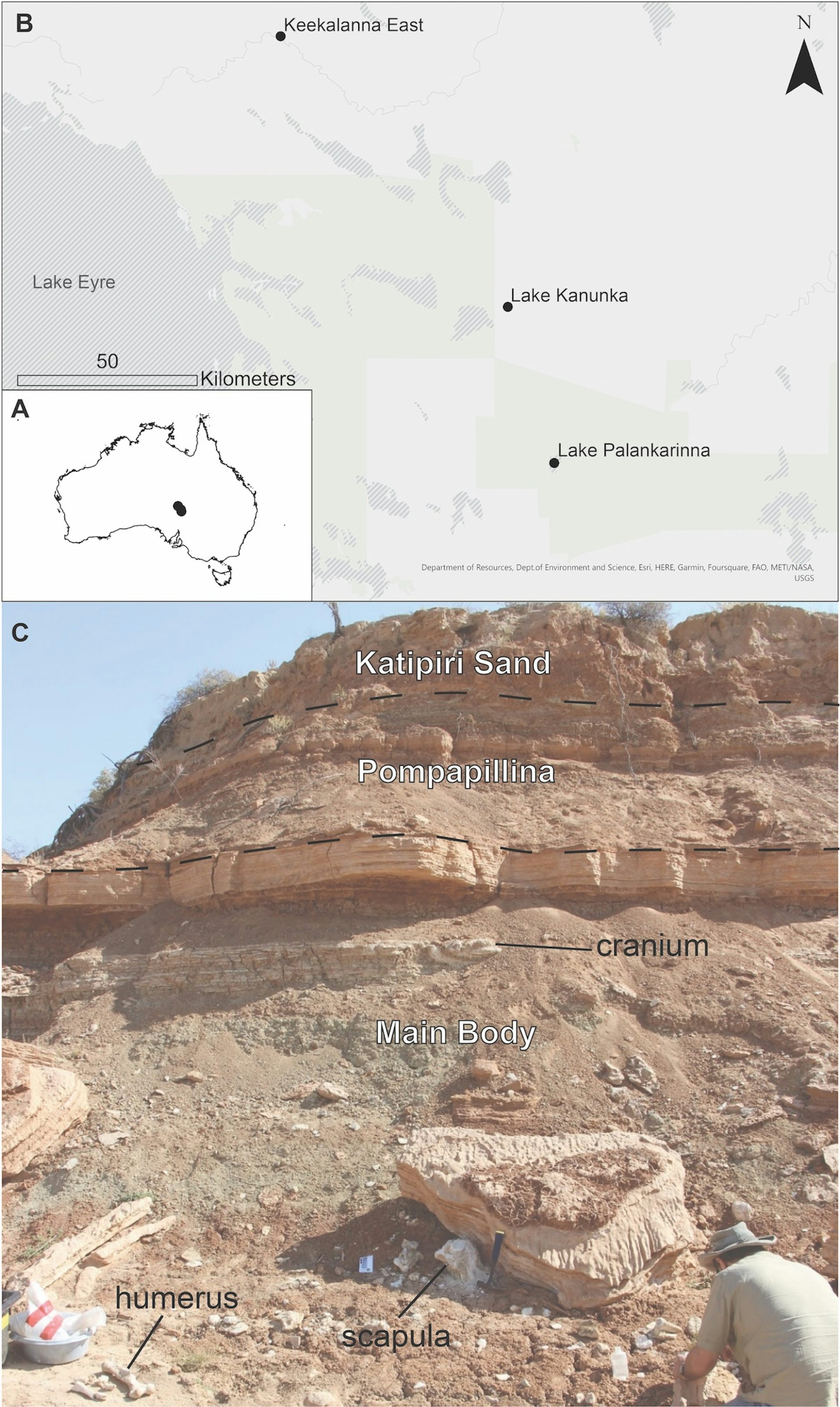

In 2017, Flinders University researchers uncovered a skeleton eroding from a cliff face on the Warburton River, at the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Kalamurina Station in northern South Australia.

The skeleton belongs to a species in the family Diprotodontidae – a group of four-legged herbivores that were the largest marsupials to ever exist.

Map of fossil deposits where the species was found (A & B). Close up of the Main Body of the Tirari Formation as exposed at Keekalanna East with some elements in situ (C).

Aaron Camens, Author provided

Exceptional preservation

Wombats are the closest living relatives of diprotodontids, but the two are as distantly related as kangaroos are to possums. As a result, palaeontologists have had a hard time reconstructing these large, long-gone animals, especially since most diprotodontid species have been described mainly from jaws and teeth.

But the common, widespread nature of diprotodontid remains indicates they were an integral part of Australian ecosystems until the last species, including the rhino-sized Diprotodon optatum, became extinct about 40,000 years ago.

It is rare to find multiple bones belonging to a single skeleton in the fossil record. Only a handful of studies have described parts of the limbs of a post-Miocene diprotodontid. As such, the newly described skeleton is of great importance and is even more special, as it is the first to be found with associated soft tissue structures.

We also compared the specimen to more than 2,000 diprotodontid elements from museums across the globe, making this the most comprehensive appraisal of a diprotodontid skeleton to date.

Our comparisons revealed the skeleton belongs to a new genus we named Ambulator, meaning walker or wanderer. We chose this name because the locomotory adaptations of the legs and feet of this quarter-tonne animal would have made it well suited to roaming long distances in search of food and water, especially when compared to earlier relatives.

We 3D-scanned the specimen, and the files are freely available for anyone to download and look at online.

Reassembled partial skeleton of Ambulator keanei, with a silhouette demonstrating advanced adaptations for its style of walking.

Jacob van Zoelen, Author provided

We don’t often think of walking as a special skill – but when you’re big, any movement can be energetically costly, so efficiency is key.

Most large herbivores today, such as elephants and rhinoceroses, are unguligrade, meaning they walk on the tips of their toes, with their wrists or ankles not touching the ground.

Diprotodontids are what we call plantigrade, meaning their heel-bone contacts the ground when they walk – similar to human feet. This stance helps distribute weight and reduces energy loss when walking, but uses more energy for other activities such as running.

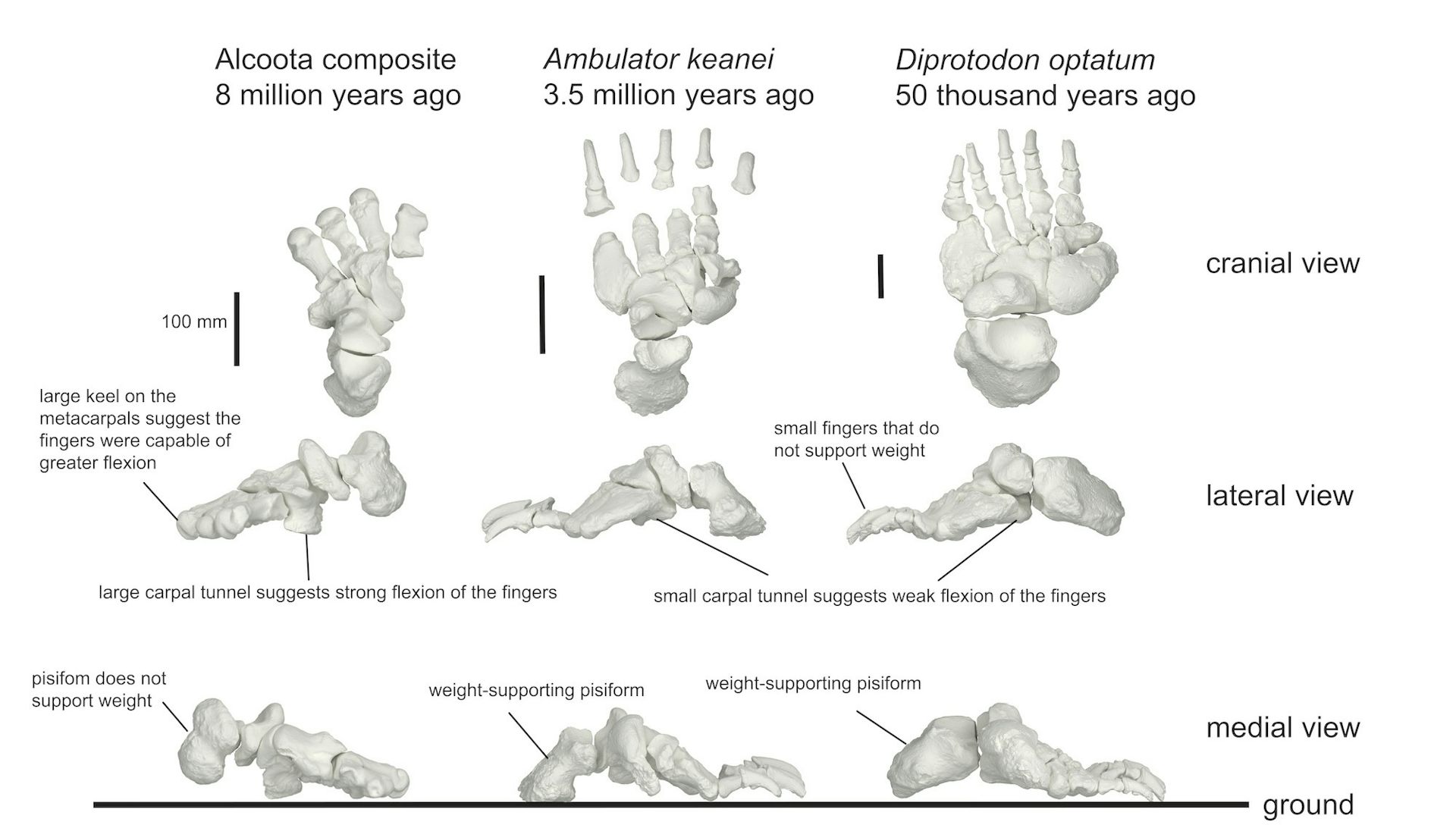

Many diprotodontids also have so-called extreme plantigrady in their hands – a wrist bone modified into a secondary heel. This “heeled hand” made early reconstructions of these animals look bizarre and awkward.

Development of the wrist and ankle for weight-bearing meant the digits became essentially functionless and likely did not make contact with the ground while walking. This may be why no finger or toe impressions are observed in the trackways of diprotodontids.

Hand and foot impression of Diprotodon optatum – with no sign of digits.

Aaron Camens, Author provided

Diprotodontids have limb-bone shapes that can be grouped into three main types. There are those adapted to tree climbing, such as Nimbadon lavarackorum and Ngapakaldia tedfordi; and those adapted to more efficient locomotion and travelling great distances, such as Diprotodon optatum and Ambulator keanei (we call these “walkers”).

There are also diprotodontids that were terrestrial and probably could not climb. However, unlike the walkers, their forelimbs were not as specialised for walking and were able to perform a range of functions. These were “grabbers” such as Neohelos stirtoni, and likely Kolopsis torus and Plaisiodon centralis.

Walkers do not show up in the fossil record until we get to the Pliocene (3.5 million years ago). In fact, A. keanei is the earliest diprotodontid we know of that had these specialised walking adaptations.

Comparisons of the left hand of three diprotodontids. From left to right a composite hand of: 8 million-year-old Alcoota diprotodontid, a grabber; 3.5 million-year-old A. keanei, a walker; and 50 thousand-year-old Diprotodon optatum, also a walker.

Jacob van Zoelen, Author provided

Animals such as Ambulator may have evolved to traverse great distances more efficiently. This may also have allowed diprotodontids to get bigger and support more weight. This would eventually lead to the evolution of the giant and relatively well-known 2.7 tonne Diprotodon.

Unfortunately, we will never get to see great migrating mobs of diprotodontids. But it’s amazing to know such a thing may have once been commonplace across the continent.

Jacob van Zoelen, PhD Candidate, Flinders University; Aaron Camens, Lecturer in Palaeontology, Flinders University, and Gavin Prideaux, Professor, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As alluded to in their article, the scientists have published their findings open access in the journal Royal Society Open Science. In their abstract, they say:

AbstractTraditionally, creationists wave this sort of scientific evidence away by claiming the scientists used wrong dating methods for no better reason than that the results are not what creationists want them to be, or they'll show their ignorance of radiometric dating by gibbering about carbon-14 dating, which isn't used to date fossils.

Diprotodontids were the largest marsupials to exist and an integral part of Australian terrestrial ecosystems until the last members of the group became extinct approximately 40 000 years ago. Despite the frequency with which diprotodontid remains are encountered, key aspects of their morphology, systematics, ecology and evolutionary history remain poorly understood. Here we describe new skeletal remains of the Pliocene taxon Zygomaturus keanei from northern South Australia. This is only the third partial skeleton of a late Cenozoic diprotodontid described in the last century, and the first displaying soft tissue structures associated with footpad impressions. Whereas it is difficult to distinguish Z. keanei and the type species of the genus, Z. trilobus, on dental grounds, the marked cranial and postcranial differences suggest that Z. keanei warrants genus-level distinction. Accordingly, we place it in the monotypic Ambulator gen. nov. We, also recognize the late Miocene Z. gilli as a nomen dubium. Features of the forelimb, manus and pes reveal that Ambulator keanei was more graviportal with greater adaptation to quadrupedal walking than earlier diprotodontids. These adaptations may have been driven by a need to travel longer distances to obtain resources as open habitats expanded in the late Pliocene of inland Australia.

van Zoelen Jacob D., Camens Aaron B., Worthy Trevor H. and Prideaux Gavin J. 2023

Description of the Pliocene marsupial Ambulator keanei gen. nov. (Marsupialia: Diprotodontidae) from inland Australia and its locomotory adaptations

R. Soc. open sci.10230211230211 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.230211

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by The Royal Society. Open access

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Their second line of defence is to claim these extinct animals were, along with dinosaurs, either on the Ark and have since either gone extinct or evolved at warp speed into something else, or failed to get on the Ark and were exterminated in their favourite genocide. In either case, there should be fossils of them all jumbled up with non-Australian species and they should be found outside Australia, because there would be nothing to stop the bodies floating from other land-masses, yet they are only found in Australia where fossils of no other continent's wildlife are ever found.

Creationists fallback strategy is to suddenly realise they are not young-Earth creationists after all and claim that, to God, millions of years can be a day, so each of the seven days of creation in the Bible refers to tens of millions of years, so, when God said 'day' in the Bible he meant to say, 'tens of millions of years' (an easy mistake to make). Although, since the Bible also says flowering plants were created a day, i.e., 'tens of millions of years', before the sun on which they depend, no creationists can ever be induced to say how green plants managed for 'tens of millions of years' before the sun was created.

The next blog-posts will look at an even older fossil unique to Australian in view of which the 3.5 million year age of this fossil is a mere blink on the geological time-scale. It is 26,750 times older than Earth according to Creationists.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.