One of the Early Cretaceous bird tracks that clearly shows all four toes, including the rear toe, or hallux. The track is nearly 10 centimeters wide and is similar in size and form to tracks made by modern-day green herons.

Photo by Melissa Lowery.

Some more of that long history of 'pre-Creation' life on Earth was revealed a couple of days ago when an international team of researchers led by Professor Anthony Martin, of Emory University’s Department of Environmental Sciences, and including researchers from Monash University and the Museums Victoria Research Institute in Australia; the Benemérita Normal School of Coahuila in Mexico; and the Smithsonian Institution, published their discovery of 27 bird tracks which vary in form and size in Early Cretaceous rocks. The tracks range from seven to fourteen centimetres wide and resemble those of modern shore birds such as small herons, waders and oystercatchers.

The discovery is published open access in PLOS ONE.

They were found in the Wonthaggi Formation south of Melbourne. The rocky coastal strata mark where the ancient supercontinent Gondwana began to break up around 100 million years ago when Australia separated from Antarctica and are the oldest bird tracks so far found.

At the time, in the rift valley that was opening up between Australia and what was to become Antarctica, the valley would have contained rivers which were subject to drastic seasonal changes between very cold, winters and several months of perpetual darkness and relatively warm summers when the river flood plain would have been home to migrant waders.

The tracks were made in successive stratigraphic layers which suggests seasonal flooding followed by gentle covering with silt or sand which preserved the footprints.

The Wonthaggi Formation is famous for its variety of polar dinosaur bones, although bird-fossil finds are extremely rare. The Cretaceous strata of the formation has yielded only one tiny bird bone — a wishbone — and a few feathers.

Birds have such thin and tiny bones. Think of the likelihood of a sparrow being preserved in the geologic record as opposed to an elephant.

Professor Anthony Martin.

Sunrise overlooking the Wonthaggi Formation on the coast of Victoria, Australia.

Photo by Anthony Martin.

Peter Swinkels uses chalk to mark the location of a track in preparation for making a resin cast.

Photo by Professor Anthony Martin.

A close-up of the chalk marking the area to be cast in resin. The casts can reveal nuances that are otherwise difficult to see.

Photo by Professor Anthony Martin.

At first I thought the tracks might have been made by young theropods, But I soon realized they were bird tracks.

In some dinosaur lineages, that rear toe got longer instead of shorter and made a great adaptation for perching up in trees.

Professor Anthony Martin.

Birds evolved from therapod dinosaurs during the Cretaceous. Early Cretaceous fossils from China show small therapod dinosaurs with hair-like filaments that appear to be proto-feathers.

The earliest-known fossil classified as a bird is Archaeopteryx lithographica. First found in 1861 in a Jurassic limestone from southern Germany, Archaeopteryx dates to about 150 million years ago and appears to be a transitional form between theropods and the birds we are familiar with today. Archaeopteryx had full-fledged feathers, a long bony tail, hands with fingers and a full set of teeth.

AbstractSo, about 120 million years ago, creatures resembling modern wading birds were wading in shallow waters in rivers in the rift valley formed between what are now Australian and Antarctic as Gondwana was breaking up, and probably treating the flood plain as a stop-over on their migration.

The fossil record for Cretaceous birds in Australia has been limited to rare skeletal material, feathers, and two tracks, a paucity shared with other Gondwanan landmasses. Hence the recent discovery of 27 avian footprints and other traces in the Early Cretaceous (Barremian-Aptian, 128–120 Ma) Wonthaggi Formation of Victoria, Australia amends their previous rarity there, while also confirming the earliest known presence of birds in Australia and the rest of Gondwana. The avian identity of these tracks is verified by their tridactyl forms, thin digits relative to track lengths, wide divarication angles, and sharp claws; three tracks also have hallux imprints. Track forms and sizes indicate a variety of birds as tracemakers, with some among the largest reported from the Early Cretaceous. Although continuous trackways are absent, close spacing and similar alignments of tracks on some bedding planes suggest gregariousness. The occurrence of this avian trace-fossil assemblage in circumpolar fluvial-floodplain facies further implies seasonal behavior, with trackmakers likely leaving their traces on floodplain surfaces during post-thaw summers.

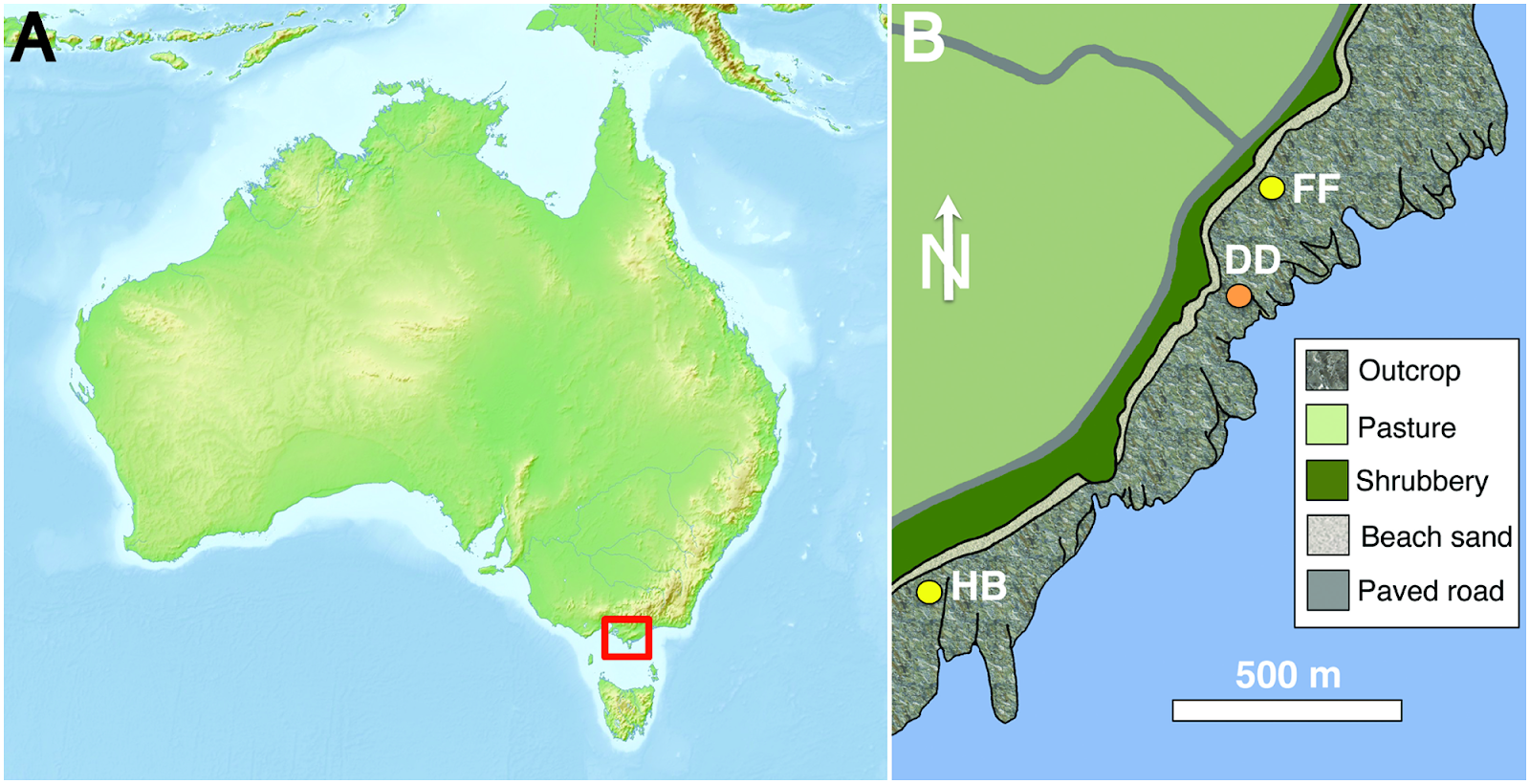

Fig 1. Locality map of Wonthaggi Formation avian tracksites, Victoria, Australia.

Fig 1. Locality map of Wonthaggi Formation avian tracksites, Victoria, Australia.

(A)Approximate outcrop area of Wonthaggi Formation indicated (red box). Map of Australia downloaded from Mapswire (https://mapswire.com/maps/australia/), which are provided under a Creative Commons (CC-BY 4.0) license; accessed and retrieved September 21, 2023. (B) Wonthaggi Formation coastal outcrops and locations of avian tracksites for this study, with “Honey Bay” (HB) at S 38° 39.9’, E 145° 40.5’ and “Footprint Flats” (FF) at S 38° 39.4’, E 145° 41.0’; “Dinosaur Dreaming” (DD) site is at S 38° 39.5”, E 145° 41.2’. Map was drawn and adapted from public-domain satellite images at EarthExplorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov). Fig 4. Polyester-resin cast duplicating tracks in rocky intertidal environment at Footprint Flats (FF) locality.

Fig 4. Polyester-resin cast duplicating tracks in rocky intertidal environment at Footprint Flats (FF) locality.

(A) Bedding planes of FF-5A (lower surface) and FF-5B (upper surface), with seven tracks (circled) photographed just before molding on November 11, 2020; ruler = 15 cm long. (B) Resin cast of bedding plane, with same seven tracks indicated; scale with centimeters. See text for key to specimen numbers, Table 1 for measurements of tracks, and S1 File for description of molding and casting methods. Fig 6. Ungual and digit impressions near a more clearly defined avian footprint in the Wonthaggi Formation, Footprint Flats.

Fig 6. Ungual and digit impressions near a more clearly defined avian footprint in the Wonthaggi Formation, Footprint Flats.

(A) Two ungual prints next to FF-4-5 (left) and a nearby incomplete track (two digits registered), with each ungual and digit denoted by arrows; ungual print behind FF-4-5 gives misleading appearance of a digit I for that track. (B) Overlay of inferred foot morphology for FF-4-5 and estimated anisodactyl-incumbent track based on two ungual prints. (C) Overlay of inferred foot morphology for incomplete track with only partial prints of two digits. For paired ungual and digit prints, one is presumed as digit III and the other as either II or IV. Photo scale = 5 millimeter squares. Fig 5. Avian track in sandy siltstone from Wonthaggi Formation at Honey Bay locality.

Fig 5. Avian track in sandy siltstone from Wonthaggi Formation at Honey Bay locality.

(A) Footprint HB-1, with digits II-IV indicated. (B) Line drawing of HB-1 footprint with overlay of inferred foot morphology. Note deformation of bedding immediately behind digit III and the remainder of the track, suggesting the possible effect of a digit I (I?). Scale = 1 cm in both. Fig 8. Wonthaggi Formation avian track with digits defined by distal ends and ungual impressions.

Fig 8. Wonthaggi Formation avian track with digits defined by distal ends and ungual impressions.

(A) Photo and (B) line drawing of track FF-5B-1 (polyester cast), interpreted as right pes, with ungual imprint of digit IV and slight disruption of bedding (arrows) as evidence for that digit, and inferred foot morphology overlain. Scale in both = 1 cm. Fig 10. Anisodactyl track FF-5B-2.

Fig 10. Anisodactyl track FF-5B-2.

(A) Outcrop view of track on November 11, 2020. (B) Polyester-resin cast of track. (C) Line drawing with overlay of inferred foot morphology. Track is interpreted as a right pes with full anisodactyl expression, sedimentary structures (ridges) in front of digits II-IV, and a thin hooked groove associated with digit I. Scale bar = 5 cm in all parts. Fig 11. Anisodactyl track FF-5B-4. (A) Outcrop view of track on May 25, 2022. (B) Line drawing with overlay of inferred foot morphology. Track is interpreted as right pes, with sedimentary structures (ridges) in front of digits II-IV and a thin linear groove associated with digit I, presumably imparted by the ungual. Scale bar = 5 cm in both parts.

Fig 11. Anisodactyl track FF-5B-4. (A) Outcrop view of track on May 25, 2022. (B) Line drawing with overlay of inferred foot morphology. Track is interpreted as right pes, with sedimentary structures (ridges) in front of digits II-IV and a thin linear groove associated with digit I, presumably imparted by the ungual. Scale bar = 5 cm in both parts. Fig 9. Differing sedimentary expressions of digit I in Wonthaggi avian tracks.

Fig 9. Differing sedimentary expressions of digit I in Wonthaggi avian tracks.

(A, B) Photo and line drawing FF-1-3, with inferred foot morphology overlain. Because digit I is clearly defined, this track is classified as anisodactyl. (C, D) Photo and line drawing of FF-1-4. A probable digit I impression in FF-1-4 is obscured by disturbed sediment behind digits II-IV. Because of this uncertainty, the latter track was classified as anisodactyl incumbent. Scale = 5 cm in both B and D. Fig 16. Invertebrate burrows and avian tracks in Wonthaggi Formation.

Fig 16. Invertebrate burrows and avian tracks in Wonthaggi Formation.

(A) Specimen FF-4-2 with oval cross-sections of sand-lined burrows closely associated with track (arrows); scale = 5 mm squares. (B) Close-up of burrow cross-sections on left side of track, with two sand-lined nearly intersecting on right; scale = 1 cm. (C) Specimen FF-5B-4 with circular cross-sections of unlined burrows (arrows); scale = 5 mm squares. (D) Line drawing of FF-5B-4 denoting locations of circular to semi-circular burrow cross-sections with track; scale = 5 cm. Fig 15. Similar orientations of closely spaced bird-track assemblages on Wonthaggi bedding planes.

Fig 15. Similar orientations of closely spaced bird-track assemblages on Wonthaggi bedding planes.

(A) Bed FF-3, with azimuth orientations between 235–340° for tracks on bedding plane. Depression denoting possible track (PT) also points in northwestern quadrant at 310°; photo scale in centimeters. (B) Bed FF-5, with azimuth orientations between 230–270° for four of five tracks on lower bedding plane (5A) and identical azimuths of 165° for two tracks on upper bedding plane (5B). Ruler (left) = 15 cm long. Fig 14. Wonthaggi bird tracks affected by modern erosion and marine organisms at Footprint Flats locality.

Fig 14. Wonthaggi bird tracks affected by modern erosion and marine organisms at Footprint Flats locality.

(A) FF-3-1-1, interpreted as left pes, with widened (eroded) digits and encrusted by algae, barnacles, and gastropods. (B) FF-3-5, interpreted as right pes, with barnacles and gastropods on track center and within digits. Scale bar = 5 cm in both. Fig 12. Closely associated Wonthaggi tracks and single-digit impression with prominent extramorphological features.

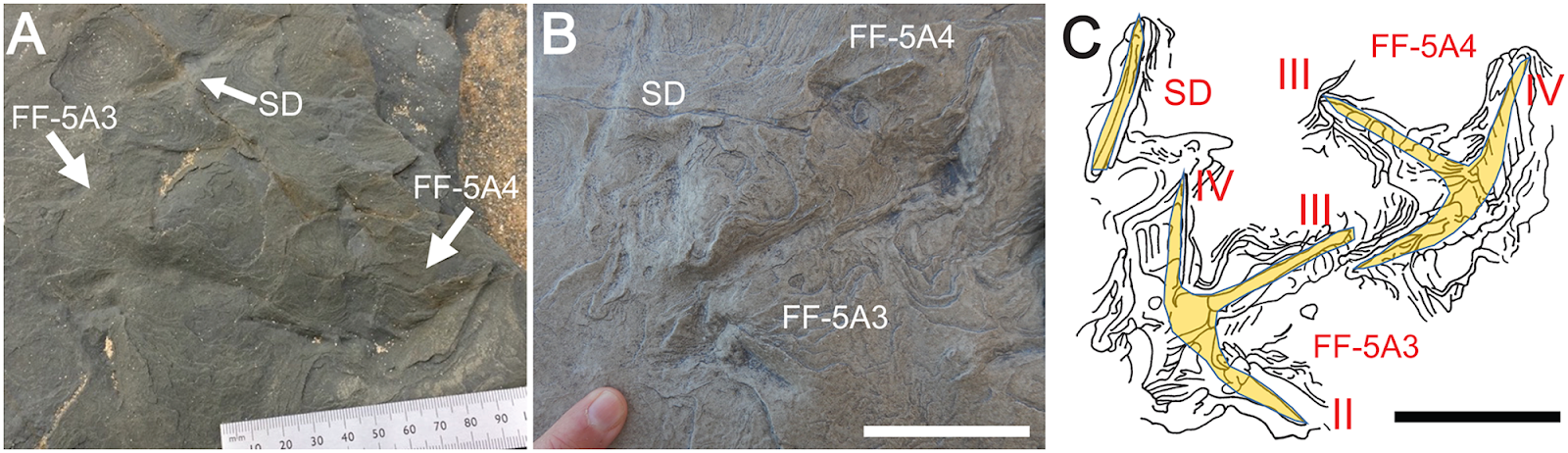

Fig 12. Closely associated Wonthaggi tracks and single-digit impression with prominent extramorphological features.

(A) Outcrop view of FF-5A3, FF-5A-4, and single digit (SD); photo taken on November 11, 2020. (B) Polyester resin cast of tracks and single-digit impression. (C) Line drawings of FF-5A-3 and FF-5A-4 tracks, single-digit impression, and extramorphological structures, with overlays of inferred foot morphology for each track and digit. Ruler in A is in millimeters, scale bar in B and C = 5 cm.

Martin AJ, Lowery M, Hall M, Vickers-Rich P, Rich TH, Serrano-Brañas CI, et al. (2023)

Earliest known Gondwanan bird tracks: Wonthaggi Formation (Early Cretaceous), Victoria, Australia. PLoS ONE 18(11): e0293308. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293308

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by PLoS. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

These were the descendant of early avian dinosaurs that were the only members of the dinosaur clade to survive the mass extinction caused by a 9-mile-wide comet striking Earth on the Edge of what is now the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, throwing hundreds of billions of tons of sulphurous dust into the atmosphere, causing a decade-long 'winter' of darkness and freezing temperatures. It may have been their small size and feathers that helped these early birds survive.

And once again we see so much of Earth's history taking place hundreds of millions of years before the Universe existed according to the childish creationist superstition.

Save 50.0% on select products from Zukro with promo code 50ZSRGHW, through 11/25 while supplies last.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.