Early Primates | | UZH

Religious fundamentalists like to assume they have ownership of the institution of marriage because the 'right' form of marriage was dictated by their imaginary god so we should all subscribe to their approved form of it. In many formerly majority Christian countries, the Christian-based marital laws are one of the few remaining vestiges of a time when Christianity imposed itself on everyone, believers, non-believers and non-Christians alike, arrogantly believing it had a divine right to rule.

But recent research has shown that a form of flexible monogamy, or more or less stable social parings of a female and a male is common if not the norm in the primate family. It was most likely incorporated into religions because some human tribes thought of monogamy as the 'right' form of sexual relationship, so any god whom the priesthood wanted to be taken seriously had to hand down 'morals' that the people thought were right and proper. After all, the only way to tell if a god is a good god or an evil god is to compare its morals and behaviour to that of an external standard of 'good', is it not?

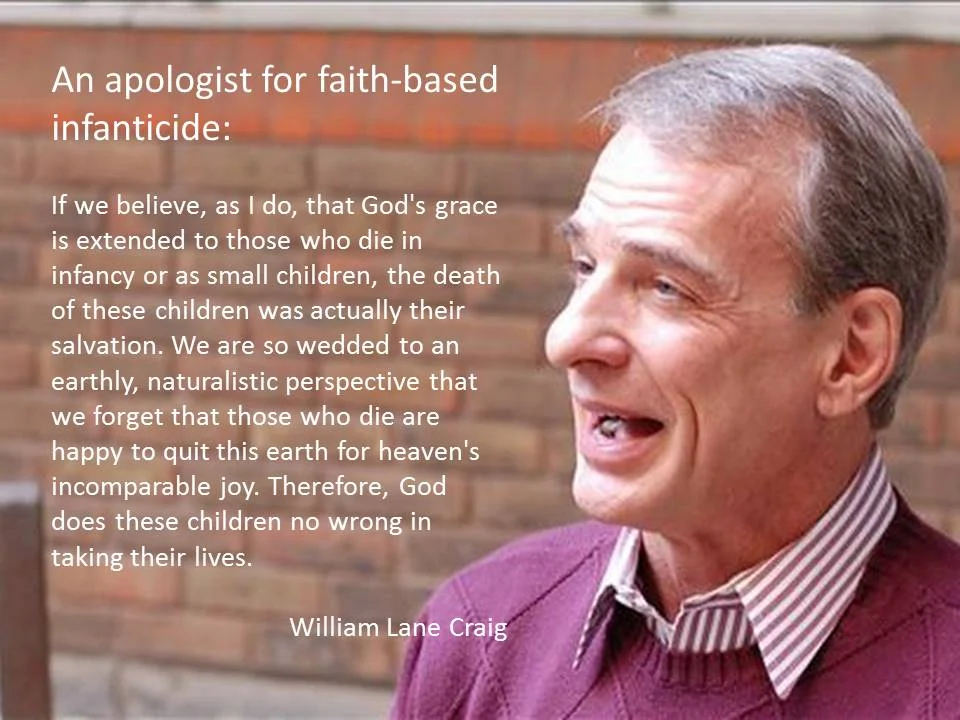

If you think not, you have to believe that if your god had told people to hurt babies, rob banks and hit old ladies, those would now be considered moral acts and people who didn't do them would be regarded as immoral and deserving of punishment or other social sanctions. Christian apologist for faith-based genocide, William Lane Craig, has even declared that a seemingly immoral act such as infanticide, is morally right if you believe his (but only his) god commands it, and it would be immoral not to carry out such a divine command.

But William Lane Craig's repugnant idea of what constitutes morality is straying somewhat off the point, which is the 'right' form of marriage in human society, which William Lane Craig presumably believes is divinely commanded by his god and therefore mandatory for the rest of us.

But, absolute monogamy is not the universal norm in modern human sexual relationships, even in societies which only permit monogamous marriage, and probably never has been. Humans can best be described as mostly monogamous, most of the time, with 'infidelity' by both sexes being fairly common to the extent that some estimates put the number of people who have a different father to the one they think is theirs at about 25%. In some cultures, such as Islamic, bigamy is normal and, as evidenced by baptism records, pre-marital sex was commonplace in 19th Century England.

What information do you have on marital infidelity in Western society including children from extra-marital relationships? Infidelity in Western society is a complex and sensitive topic that can vary widely based on cultural, social, and individual factors. It's important to note that generalizations may not capture the diversity of experiences and perspectives within Western societies. However, I can provide some general information on the topic:The recent research was conducted by a team from the Universities of Zurich, Switzerland, Strasbourg, France and Tennessee, USA, who believe they have shown that early social grouping of primates were often male and female pairs, rather than solitary individuals, as had been assumed.It's essential to recognize that every individual and relationship is unique, and the impact of infidelity can vary widely. Open communication, trust-building, and seeking professional help when needed are crucial aspects of addressing and resolving issues related to infidelity in Western societies.

- Prevalence:

- Studies suggest that rates of infidelity can vary but estimates often range from 20% to 50% of married individuals admitting to having engaged in extramarital affairs at some point in their lives.

- Technology, such as dating apps and social media, has been cited as a factor influencing the ease of engaging in extramarital relationships.

- Impact on Marriages:

- Infidelity can have profound effects on marriages, often leading to emotional distress, trust issues, and, in some cases, divorce.

- Couples may choose to seek therapy or counseling to navigate the challenges arising from infidelity and work towards rebuilding trust.

- Children from Extra-Marital Relationships:

- Children born as a result of extramarital affairs may face unique challenges related to their parentage and family dynamics.

- The revelation of such affairs can have significant emotional and psychological impacts on the children, the betrayed spouse, and the individual who engaged in infidelity.

- Cultural and Societal Attitudes:

- Attitudes toward infidelity vary across cultures and societies. Some societies may be more permissive or forgiving, while others may view infidelity as a severe breach of trust.

- Cultural shifts and changing societal norms can influence how infidelity is perceived and dealt with.

- Legal Implications:

- In terms of legal consequences, some jurisdictions have no-fault divorce laws, which means that infidelity may not play a role in divorce proceedings. However, in certain cases, it can still affect issues like alimony or child custody.

- Online Infidelity:

- The rise of the internet and social media has introduced new avenues for infidelity. Online relationships, including emotional affairs and virtual connections, can contribute to marital issues.

Is 25% a realistic estimate of the percentage of children who result from an extra-marital relationship?

Estimating the percentage of children born as a result of extramarital relationships is challenging, and specific figures can vary based on the sources and methodologies used in studies. The reported percentage of children born from extramarital relationships may range, and it's important to interpret such figures with caution.

The suggested figure of 25% is within the range of estimates that researchers and demographers often cite. However, it's essential to consider that these numbers are approximate and can vary based on factors such as cultural norms, societal attitudes toward infidelity, and individual behaviors.

Moreover, reporting accuracy is a significant challenge in studies on sensitive topics like extramarital affairs and their consequences. People may underreport such experiences due to social desirability bias or concerns about privacy.

To get the most accurate and current information on this specific aspect, it would be advisable to refer to recent and reputable demographic studies or surveys that specifically address the prevalence of children born from extramarital relationships in the context of the region or population of interest.

This means that the tendency to form monogamous relationships may be a trait inherited from a common primate ancestor, not the handed-down 'normal' marital state of a god and enforced by its priesthood.

The team's research is explained in a press release from Zurich University. Their findings are also published, open access, in the journal Proceeding of the National Academy of Science (PNAS):

Primates – and this includes humans – are thought of as highly social animals. Many species of monkeys and apes live in groups. Lemurs and other Strepsirrhines, often colloquially referred to as “wet-nosed” primates, in contrast, have long been believed to be solitary creatures, and it has often been suggested that other forms of social organization evolved later. Previous studies have therefore attempted to explain how and when pair-living evolved in primates.In their published paper, the team say:

More recent research, however, indicates that many nocturnal Strepsirrhines, which are more challenging to investigate, are not in fact solitary but live in pairs of males and females. But what does this mean for the social organization forms of the ancestors of all primates? And why do some species of monkey live in groups, while others are pair-living or solitary?

Different forms of social organization

Researchers at the Universities of Zurich and Strasbourg have now examined these questions. For their study, Charlotte Olivier from the Hubert Curien Pluridisciplinary Institute collected detailed information on the composition of social units in primate populations in the wild. Over several years, the researchers built a detailed database, which covered almost 500 populations from over 200 primate species, from primary field studies.

More than half of the primate species recorded in the database exhibited more than one form of social organization. “The most common social organization were groups in which multiple females and multiple males lived together, for example chimpanzees or macaques, followed by groups with only one male and multiple females – such as in gorillas or langurs,” says last author Adrian Jaeggi from the University of Zurich. “But one-quarter of all species lived in pairs.”

Smaller ancestors coupled up

Taking into account several socioecological and life history variables such as body size, diet or habitat, the researchers calculated the probability of different forms of social organization, including for our ancestors who lived some 70 million years ago. The calculations were based on complex statistical models developed by Jordan Martin at UZH’s Institute of Evolutionary Medicine.

To reconstruct the ancestral state of primates, the researchers relied on fossils, which showed that ancestral primates were relatively small-bodied and arboreal – factors that strongly correlate with pair-living. “Our model shows that the ancestral social organization of primates was variable and that pair-living was by far the most likely form,” says Martin. Only about 15 percent of our ancestors were solitary, he adds. “Living in larger groups therefore only evolved later in the history of primates.”

Pairs with benefits

In other words, the social structure of early primates was likely more similar to that of humans today than previously assumed. “Many, but by no means all of us, live in pairs while also being a part of extended families and larger groups and societies,” Jaeggi says. However, pair-living among early primates did not equate to sexual monogamy or cooperative infant care, he adds. “It is more likely that a specific female and a specific male would be seen together for most of the time and share the same home range and sleeping site, which was more advantageous to them than solitary living,” explains last author Carsten Schradin from Strasbourg. This enabled them to fend off competitors or keep each other warm, for example.

SignificanceIt is clear that what human societies regard as the norm in human sexual relationships is inherited from our common ancestry, and it is our innate ideas of what form that should take that has been incorporated into religions as societies evolved and diversified. The way we behave is influenced far more by our common ancestry than the transient notions over time that religions have tried to impose on us - religions that their dogmatic followers require to set down rigid absolute rules and to then impose them on the rest of us, as, like William Lane Craig, they use religion as an excuse to impose their will on society and command us to obey them.

Was the ancestor of all primates a solitary-living species? Did more social forms of primate societies evolve from this basic and simple society? Until now, the dogmatic answer was yes. We used a modern statistical analysis, including variations within species, to show that the ancestral primate social organization was most likely variable. Most lived in pairs, and only 10 to 20% of individuals were solitary. Living in pairs was likely ancient and caused by reproductive benefits, like access to partners and reduced competition within the sexes.

Abstract

Explaining the evolution of primate social organization has been fundamental to understand human sociality and social evolution more broadly. It has often been suggested that the ancestor of all primates was solitary and that other forms of social organization evolved later, with transitions being driven by various life history traits and ecological factors. However, recent research showed that many understudied primate species previously assumed to be solitary actually live in pairs, and intraspecific variation in social organization is common. We built a detailed database from primary field studies quantifying the number of social units expressing different social organizations in each population. We used Bayesian phylogenetic models to infer the probability of each social organization, conditional on several socioecological and life history predictors. Here, we show that when intraspecific variation is accounted for, the ancestral social organization of primates was inferred to be variable, with the most common social organization being pair-living but with approximately 10 to 20% of social units of the ancestral population deviating from this pattern by being solitary living. Body size and activity patterns had large effects on transitions between types of social organizations. As in other mammalian clades, pair-living is closely linked to small body size and likely more common in ancestral species. Our results challenge the assumption that ancestral primates were solitary and that pair-living evolved afterward emphasizing the importance of focusing on field data and accounting for intraspecific variation, providing a flexible statistical framework for doing so.

Understanding primate social evolution is central to understanding our own social ancestry. Numerous comparative studies have inferred that the ancestor of all primates was nocturnal, small, arboreal, and solitary (1–5). Previous research explained transitions from solitary living to pair- and group-living by various ecological factors and life history traits (1–3, 6, 7). The inferred ancestral solitary stage hinged largely on Strepsirrhines (among the extant primates), which are understudied and previously often assumed to be solitary living (8). However, several field studies over the last decades indicate Strepsirrhines to be more social (1, 8) and often pair-living (9).

Social systems are composed of different components including the social organization (composition of social units), social structure (interactions between individuals), care system (who cares for infants), and mating system (who mates with who) (10, 11). It has been argued that these components should be studied independently from each other to understand social evolution, especially in primates (1, 12–14). For example, pair-living as a form of social organization has often been equated with monogamy, even though monogamy refers to a mating system (1, 12, 13, 15–17). Importantly, pair-living species can vary significantly in their mating system, e.g., in the degree of extra-pair paternity (18, 19). Similarly, primate social organization varies greatly between (1, 3) but also within species (8, 20). Previous studies were statistically limited by assigning a single type of social organization to each species, such that the analysis could only consider between but not within species variation (2, 3, 21). Here, we examined whether taking intraspecific variation in social organization (IVSO) into account and focusing on data from field studies, including many recent studies on nocturnal strepsirrhines, but excluding assumptions about nonstudied species, changes our estimate of the ancestral primate social organization. Intraspecific variation in primate social behaviour has long been recognised (22), and a few studies were successful in incorporating it into phylogenetic comparative studies (23). For example, considering intraspecies variation in primate group size did not alter conclusions of the social brain hypothesis predicting larger neocortex ratios in species with larger groups (24), but it remains to be tested whether intraspecific variation influenced other aspects of social evolution. Primate social evolution is assumed to largely depend on ecology and life history (25, 26). For example, small nocturnal species living in forests are generally assumed to be solitary and large diurnal species living in open habitat to be group-living, with group composition (one or multimale groups) depending on diet (3 10, 25). Species living in heterogeneous habitats are predicted to have a more variable social organization (27). Therefore, we tested whether these ecological and life history factors influenced primate social organization (SI Appendix, Table S3).

We assembled a database on the social organization of 493 populations of 215 primate species observed in the field, as published in the primary peer-reviewed literature. A population consists of individuals of a species that live in the same geographic area and can potentially mate and interact with each other. For our study, a population refers to the animals studied at one particular field site, even though in most cases the population would have consisted of many more social units than those observed in the study area. A social unit consisted of individuals being observed consistently together either during foraging or at sleeping sites, and which were sharing the same home range (home range overlap >50% during the study period). Studies varied considerably in duration and research effort, and species varied in life history (e.g., lifespan), making it difficult to find a definition of being “consistently together” that could apply to all studies. Consistently therefore means consistently within the duration of the study, which in most cases varied from months to years.

Rather than selecting a single social organization per species, we treated each study population as the unit of analysis. Within each population, we counted the number of social units exhibiting different social organizations, allowing us to quantify within-population variation (Fig. 1). Therefore, our statistical approach allowed us to consider variation in social organization i) between species, ii) between populations of the same species, and iii) between social units within populations. We developed a flexible Bayesian phylogenetic GLMM framework to partition this extensive variation in social organization across populations, species, and superfamilies, as well as to evaluate its phylogenetic and socioecological determinants. Using a multinomial likelihood, we modelled the relative frequency of each social organization being observed within each population, adjusting for phylogeny and research effort within superfamilies (a more direct measure of the effects of research effort per se, independently of unbalanced sampling across superfamilies). We defined the “primary social organization” as the social organization with the greatest probability of being observed within a population. As a second response variable in the same model, we used a binomial likelihood to directly account for the degree of intrapopulation variation in social organization (IVSO) observed in each population, calculated as the proportion of social units deviating from the most frequent social organization (Fig. 1). This allowed us to estimate effects of socioecology and phylogeny on IVSO, irrespective of the relative probabilities of specific social organizations within a population. Both models accounted for the total number of social units, thus weighing larger studies more heavily.

The distribution of social organizations across extant primate populations. The Top panel demonstrates how we coded social organization per population as solitary, male-female (MF) or pair living, single male multifemale (MFF), single female multimale (FMM), or multimale and multifemale (MMFF). Three examples taken from field research on the slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus), common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), and lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) are shown. Large circles (Middle) around pictures represent different populations of the species. Smaller circles within each large circle represent a single social unit within a population, with color corresponding to the social organization observed. The phylogeny reflects a simple contour mapping of overall IVSO (# units deviating from primary social organization/total # units) across taxa in our database. Note that the branch lengths have been arbitrarily modified for visual clarity and should not be directly interpreted. The Lower panel shows the total number of populations in our dataset exhibiting each form of primary social organization, as well as overall IVSO (binwidth = 0.05). Left, primary SO: Dark gray bars represent uncertainty in the primary social organization for populations exhibiting two social organization with equally high frequency. Right, overall IVSO: Light gray hashed bars represent uncertainty in the level of IVSO due to studies including only a single social unit.

The distribution of social organizations across extant primate populations. The Top panel demonstrates how we coded social organization per population as solitary, male-female (MF) or pair living, single male multifemale (MFF), single female multimale (FMM), or multimale and multifemale (MMFF). Three examples taken from field research on the slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus), common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), and lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) are shown. Large circles (Middle) around pictures represent different populations of the species. Smaller circles within each large circle represent a single social unit within a population, with color corresponding to the social organization observed. The phylogeny reflects a simple contour mapping of overall IVSO (# units deviating from primary social organization/total # units) across taxa in our database. Note that the branch lengths have been arbitrarily modified for visual clarity and should not be directly interpreted. The Lower panel shows the total number of populations in our dataset exhibiting each form of primary social organization, as well as overall IVSO (binwidth = 0.05). Left, primary SO: Dark gray bars represent uncertainty in the primary social organization for populations exhibiting two social organization with equally high frequency. Right, overall IVSO: Light gray hashed bars represent uncertainty in the level of IVSO due to studies including only a single social unit.

Olivier, Charlotte-Anaïs; Martin, Jordan S.; Pilisi, Camille; Agnani, Paul; Kauffmann, Cécile; Hayes, Loren; Jaeggi, Adrian V.; Schradin, C. Primate social organization evolved from a flexible pair-living ancestor

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023) 121(1), e2215401120. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2215401120.

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by Published by PNAS. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.