Alphonse Mucha and Art Nouveau: 100 years after its creation, his work is still a balm for a world in upheaval

Some readers might have been surprised to see me posting an article about an acknowledged mystic who saw a close relationship between Slav nationalism and religion, but to me Alphons Mucha is very much like the Irish patriots who identified Catholicism with Irish nationalism, not because they believed in Papal authority and the divine right of priests to meddle in national affairs but because Catholicism was a part of the identity of the Celtic Irish. So, Mucha saw the struggle for Slav self-determination as closely tied to the struggles against Catholicism, Eastern Orthodox Christianity and later Germanic Protestantism.

Like Irish History, Slav history too can be seen as an illustration of how religion poisons everything, as the Czech people seem to have realised, since they are now second only to France in the proportion of the population who openly self-identify as Atheists.

So, it's interesting to read the following article by Will Visconti, a member of the teaching staff in the Department of Art History, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia, introducing an exhibition of Alphons Macha's work in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. I've reproduced it here under a Creative Commons license as a sort of sequel to my earlier article om Mucha's Slav Epic. The article is reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Alphonse Mucha and Art Nouveau: 100 years after its creation, his work is still a balm for a world in upheaval

Alphonse Mucha ‘Reverie’ 1898, colour lithograph, 72.7 x 55.2 cm

Will Visconti, University of Sydney

Alphonse Mucha’s body of work is full of contradictions. © Mucha Trust 2024

He is most often identified with late 19th-century Paris, but was in fact Moravian (Czech). His vision for the purpose of art was for the betterment of humanity and creation of utopia, but his most famous artworks are advertisements. His style typifies Art Nouveau, a movement at its peak between the 1890s and 1910s, but his career spanned several decades from the late 1800s until his death in 1939.

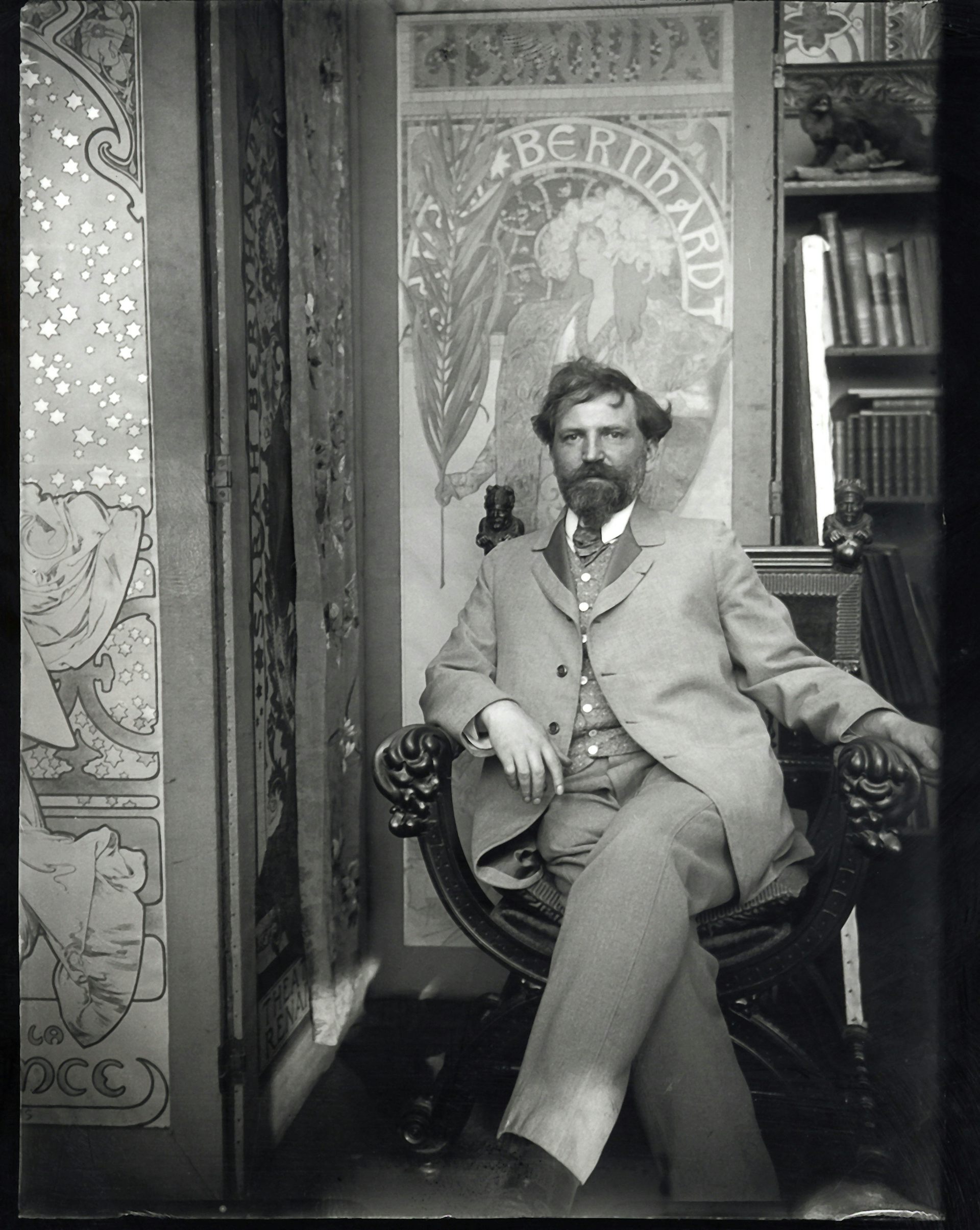

Self-portrait with posters for Sarah Bernhardt at Mucha’s studio in rue du Val-de-Grâce, Paris, c1901 © Mucha Trust 2024.

A new exhibition of his work at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the largest of its kind seen in Australia with over 200 pieces on display, shows the full breadth of Mucha’s work and his commitment to the transformative power of art across media.

Art and ideals

The twin concerns of Mucha’s art are beauty and identity, specifically, national identity.

This may provide the biggest surprise to viewers who recognise his work, showing the extent of his productivity over so many decades and multiple media. Not only did Mucha compose his iconic posters and design jewellery, but he created murals for Czech municipal buildings and a portfolio of designs for interiors.

Significantly, he also designed postage stamps and banknotes in 1918 for the newly-formed Republic of Czechoslovakia.

His work is suffused with his utopian ideals and vision for a better world. For Mucha, art was for all. He believed in the power of art to make the world kinder and more beautiful. Such was the popularity of his posters that people removed them as soon as they were put up, to keep for themselves.

His works define the Art Nouveau (“new art”) style of the late 1800s, full of dynamic natural forms or shapes. The vines and flowers that decorate and frame Mucha’s artworks are also found in art, architecture and interior design.

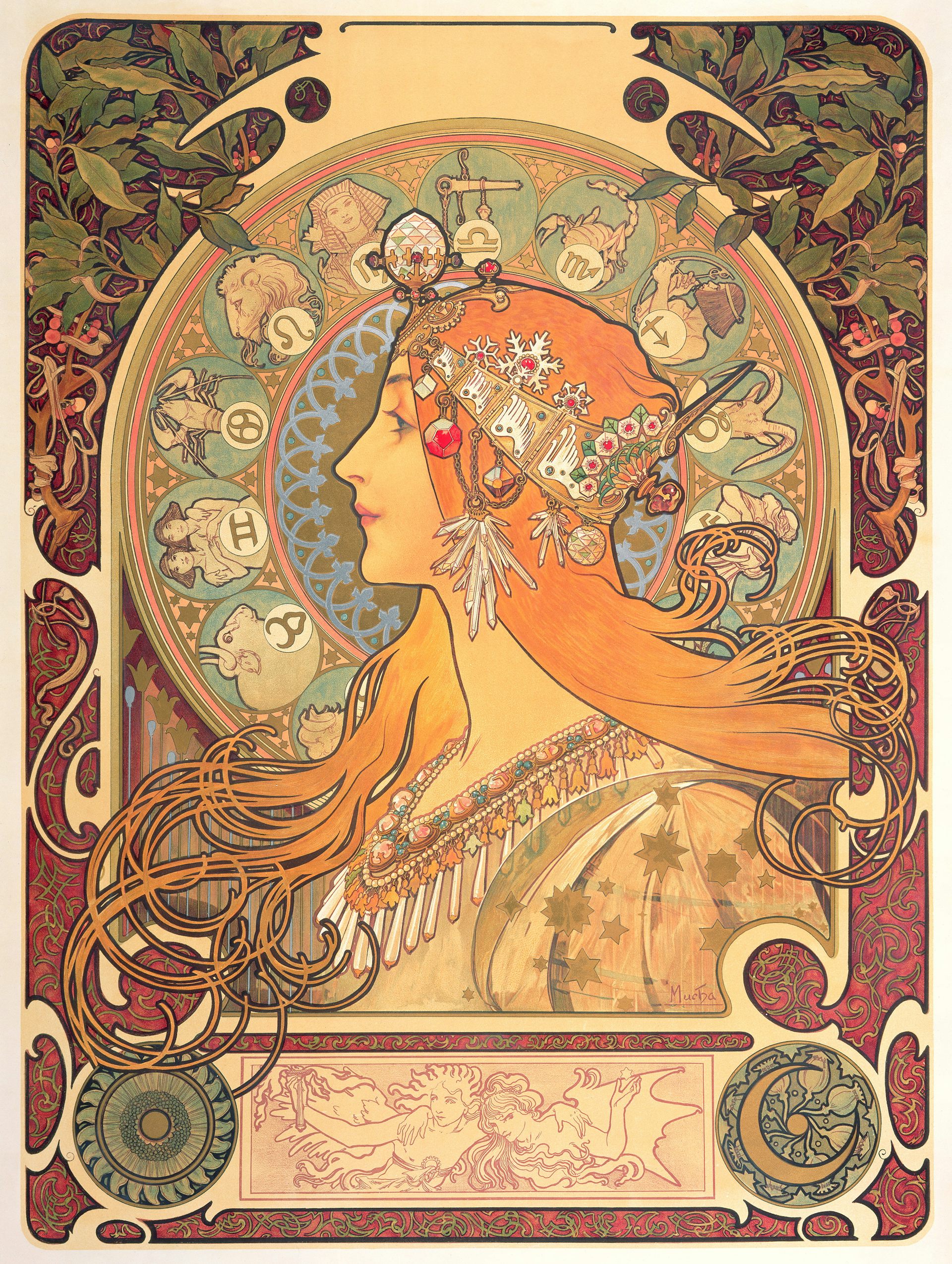

L Alphonse Mucha, Zodiac. 1896, colour lithograph 65.7 x 48.2cm, The Mucha Collection © Mucha Trust 2024.

Celebrity and brand development

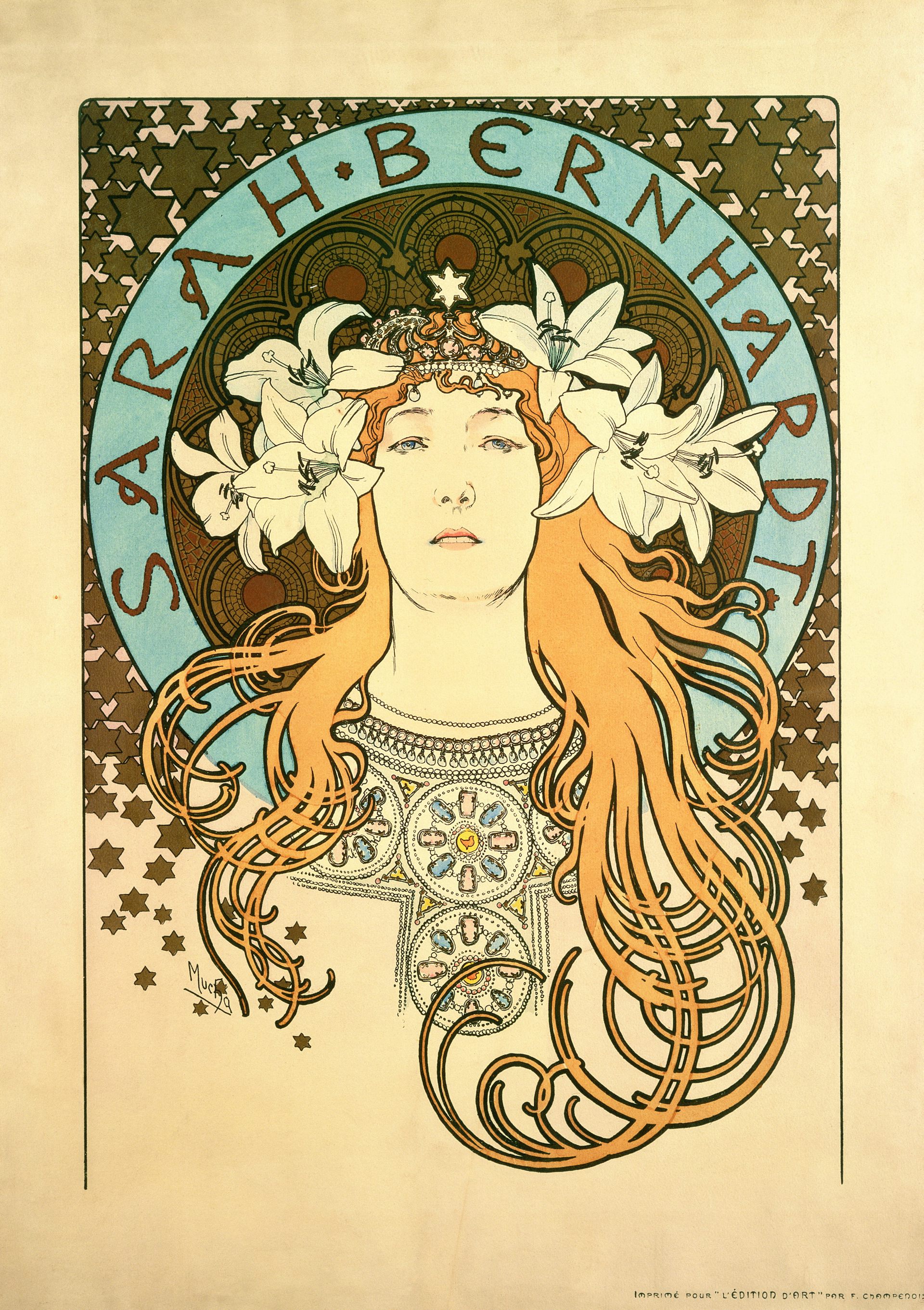

After the internationally-renowned actor the “Divine” Sarah Bernhardt, commissioned Mucha for a last-minute poster design, his own celebrity increased. Mucha began work on the poster for Bernhardt’s play, Gismonda, on Boxing Day 1894, and it was ready by New Year’s Day 1895. So began a fruitful relationship between the two.

Installation view of the Alphonse Mucha: Spirit of Art Nouveau exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 15 June – 22 September 2024.

Photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Diana Panuccio

Adjacent to these images conveying the glamour of celebrity and consumerism, the exhibition includes several works that highlight Mucha’s engagement with spirituality, Freemasonry and mysticism.

Alphonse Mucha, Sarah Bernhardt: La Plume art edition poster. 1897, colour lithograph, 69 x 51 cm © Mucha Trust 2024.

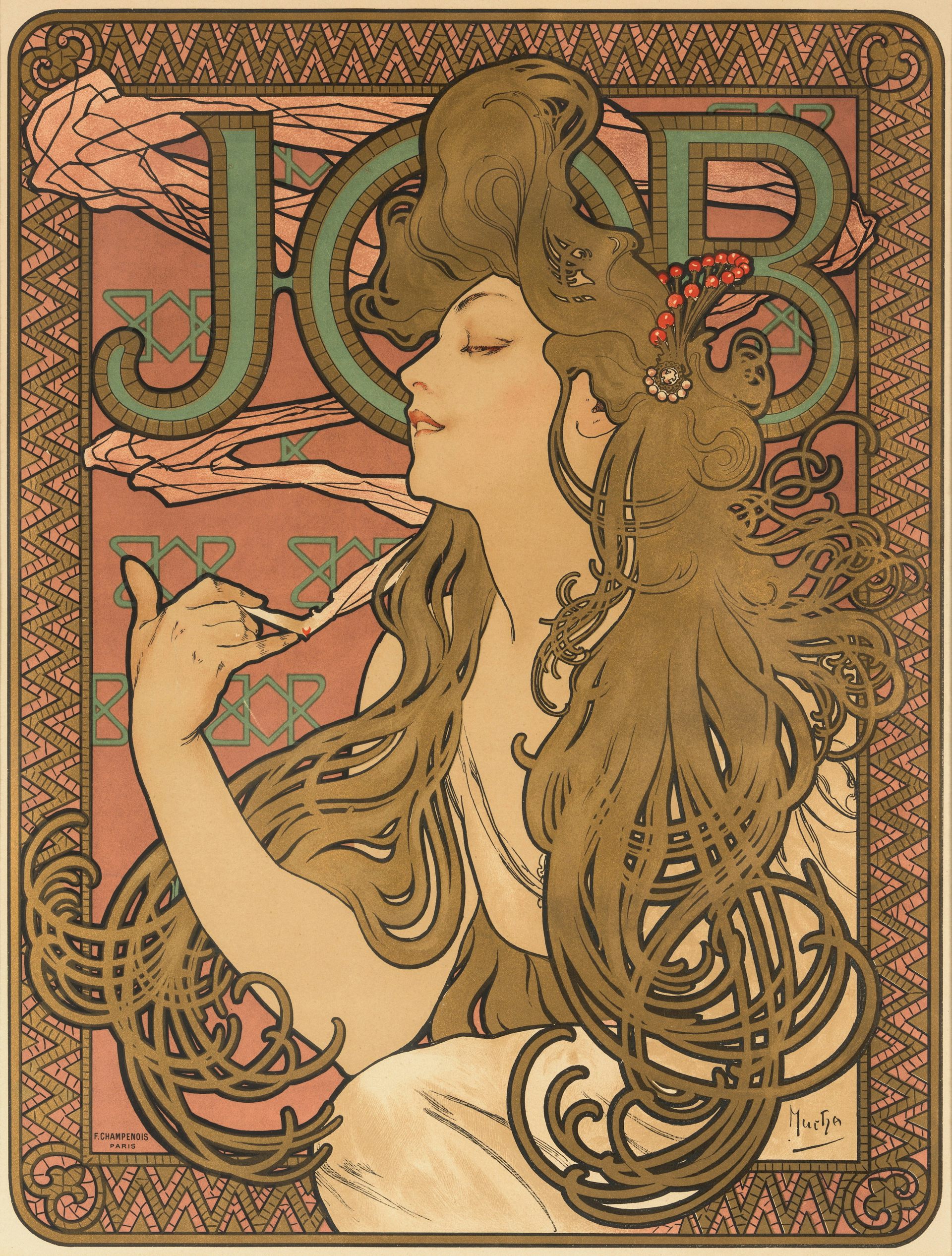

By depicting lissom women in a recognisable style, products grabbed attention without necessarily being depicted, as with JOB cigarettes or Moët & Chandon.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for JOB cigarette papers. 1896, colour lithograph, 66.7 x 46.4 cm © Mucha Trust 2024.

Since his teen years, Mucha had a sense of patriotism, expressed first through amateur dramatics and later through his artworks.

This patriotic fervour is best encapsulated in the monumental Slav Epic, 20 canvases tracing pivotal episodes in Slavic history. The work was intended to educate and inspire the Slavic people to build a peaceful future and learn from their past. It is crowned with a golden Christ-like figure to embody the new republic.

Alphonse Mucha, The Slav Epic XX: Apotheosis Slavs for Humanity. 1926 (detail) egg tempera and oil on canvas, 480 x 405 cm © Mucha Trust 2024.

It offers a chance to experience the grandeur of the works, the richness of the colours and imagery, all treated with Mucha’s eye for detail.

A final display shows both the links to Japanese art in Mucha’s works and the broader taste for Japonisme during the late 1800s. The same influence is seen beyond this exhibition in Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, with their use of flowing black lines or a limited palette. There are also manga, showing the legacy of Mucha’s artworks now reflected back in Japanese art and album covers. Groups like The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane reproduced or appropriated Mucha posters, drawing on their iconic status and melding it with a psychedelic sensibility.

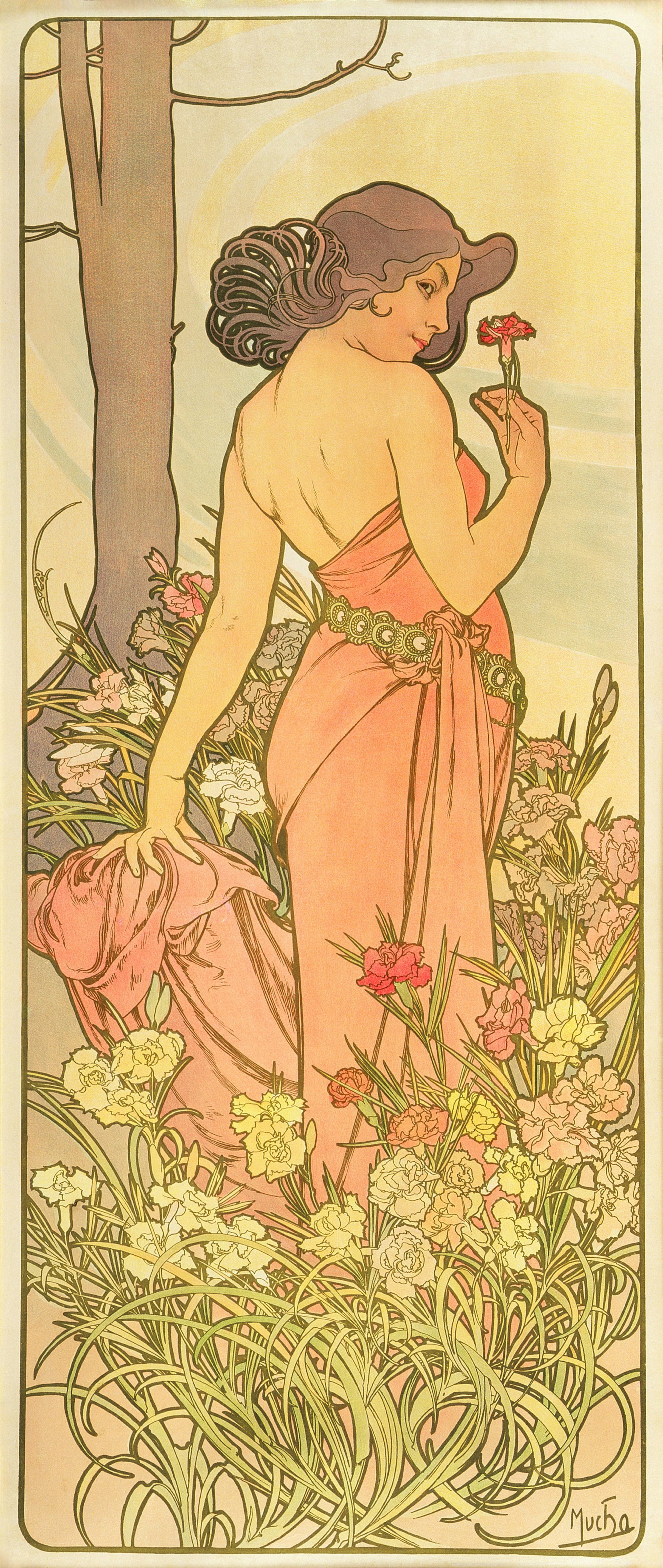

Alphonse Mucha, The Flowers: Carnation. 1898, colour lithograph on paper,107.5 x 47 cm.

© Mucha Trust 2024

Alphonse Mucha: Spirit of Art Nouveau is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until September 22.

Will Visconti, Teaching staff, Art History, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.