Oldest known picture story is a 51,000-year-old Indonesian cave painting | Archaeology | The Guardian

Another drop in the torrent of counter-evidence engulfing creationism came today with the news that a team of archaeologists led by experts from Griffith University, Australia have dated a painting found in a cave in the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, to be from at least 41,200 years before the legendary 'Creation Week'. This adds yet more data to the mountain of evidence showing the authors of Genesis didn't know what they were taking abut so just made stuff up.

To be fair to the story-tellers, how could they possibly have known about caves in Indonesia, let along what early humans had been doing in them? They thought the Universe was a small, flat place with a dome over it, centred on the Middle East.

Tell me all about the paintings found in caves in the Indonesia islands, particularly Sulawesi, please. The cave paintings found in the Indonesian islands, particularly on Sulawesi, are among the oldest known artworks in the world. These paintings provide critical insights into the early development of human artistic expression and cognitive abilities.The paintings were made by early Homo sapiens as they migrated from Africa across Asia and into Southeast Asia and Australia, reaching there at least 50,000-60,000 years ago. The discovery is the subject of an open access paper in Nature and is explained in a Griffith University media release.

Discovery and Significance

Types of Paintings

- Age and Dating:

- The cave paintings in Sulawesi have been dated to at least 40,000 years old, making them contemporaneous with or even older than the famous cave art in Europe, such as those in Spain and France.

- Dating was primarily conducted using uranium-series dating of the calcium carbonate deposits that had formed over the paintings.

- Location:

- These artworks are primarily found in the Maros-Pangkep karst region of South Sulawesi. The limestone caves in this area have preserved the paintings remarkably well.

Techniques and Materials

- Hand Stencils:

- One of the most common motifs is hand stencils, created by placing a hand against the cave wall and blowing pigment around it. These stencils are often detailed, showing fingers spread wide.

- Some of these stencils are among the oldest dated art pieces, with one found to be around 39,900 years old.

- Animal Figures:

- Animal depictions, particularly of wild mammals such as anoas (a type of small buffalo) and wild pigs, are prevalent.

- These images are often quite detailed and sophisticated, indicating a high level of skill and observation.

- Scenes and Narrative Art:

- One of the most striking findings is a scene depicting human-like figures hunting animals. This scene, discovered in the Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4 cave, has been dated to at least 43,900 years old.

- This narrative art suggests early humans in this region were capable of complex storytelling and symbolic thought.

Cultural and Anthropological Significance

- Pigments:

- The primary pigments used in these paintings were red and mulberry-colored ochres. These pigments were likely derived from locally available minerals.

- Techniques:

- The application techniques include blowing pigment through tubes (possibly hollow bones) for stenciling and direct application for drawing animals and scenes.

Conservation and Challenges

- The Sulawesi cave paintings are crucial for understanding the migration and cognitive development of early humans. They provide evidence that artistic expression was a widespread and possibly simultaneous development among early human populations in both Europe and Southeast Asia.

- These artworks also offer insights into the fauna and environment of the region during the late Pleistocene, as well as the social and spiritual lives of the people who created them.

Conclusion

- Preserving these ancient artworks is challenging due to natural weathering, human interference, and environmental changes. Conservation efforts are ongoing, with a focus on protecting the caves from further damage and ensuring that these historical treasures are maintained for future study and appreciation.

The cave paintings of Sulawesi are a testament to the early and sophisticated artistic endeavors of prehistoric humans. They represent some of the oldest known evidence of symbolic thinking and artistic expression, significantly contributing to our understanding of human cognitive evolution and the spread of early human cultures across the globe.

Would a date of 51,200 years ago be a problem for the conclusion that they were made by early Homo sapiens?

A date of 51,200 years ago for the cave paintings in Sulawesi would still be consistent with early Homo sapiens being the creators, but it would add complexity to our understanding of the timeline of human migration and artistic development. Here’s an analysis of how this earlier date fits into the broader picture:

Compatibility with Homo sapiens

Challenges and Considerations

- Early Migration:

- Evidence suggests that Homo sapiens began migrating out of Africa around 70,000 to 60,000 years ago, reaching Southeast Asia and Australia by at least 50,000 to 60,000 years ago.

- A date of 51,200 years ago for the Sulawesi paintings fits within this timeframe, supporting the idea that early Homo sapiens could have been present in the region and capable of creating art.

- Advanced Cognitive Abilities:

- The advanced nature of the artwork aligns with the known cognitive capabilities of Homo sapiens. By this time, humans had already developed complex symbolic thinking and artistic expression, as evidenced by artifacts from other regions.

Broader Implications

- Sparse Evidence:

- While there is substantial evidence of early Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia, direct archaeological evidence from the same period in the immediate vicinity of the Sulawesi caves is sparse. More discoveries would strengthen the connection between the paintings and Homo sapiens.

- Comparison with Other Sites:

- Most other early cave art sites, such as those in Europe (Chauvet Cave, 37,000 years ago) and Africa (Blombos Cave, 73,000 years ago), have somewhat different timelines. However, these sites demonstrate that early humans were creating symbolic art tens of thousands of years ago.

- Potential Overlaps with Other Hominins:

- There is ongoing debate about interactions between Homo sapiens and other hominins, such as Denisovans, in Asia. While Homo sapiens are the most likely artists, it's worth considering the broader hominin context of the region.

Redefining Human Migration Timelines:

- A 51,200-year-old date would reinforce the idea that Homo sapiens migrated and established themselves in various regions earlier than previously confirmed by direct archaeological evidence.

- It would encourage further research into early human presence and activities in Southeast Asia.

Early Artistic Development: Conclusion

- This date would push back the timeline for the emergence of complex symbolic behavior and artistic expression, suggesting that such abilities were developed shortly after Homo sapiens left Africa.

The date of 51,200 years ago for the Sulawesi cave paintings supports the conclusion that they were created by early Homo sapiens, fitting within the known migration and cognitive development timelines. While this date is earlier than some other known sites, it aligns with the broader evidence of early human capabilities and migrations. Further discoveries and research will continue to refine our understanding of these ancient artworks and their creators.

Cave painting in Indonesia is the oldest known ‘picture story’Before looking at the technical details from the published paper in Nature I'll deal with the dating method (LA-U-series) the team used with an AI description of it and how it works:

A team of scientists co-led by researchers from Australia’s Griffith University, the Indonesian National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) and Southern Cross University has discovered and dated a cave painting on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi that may be the oldest known evidence of storytelling in art, with the findings published in the journal Nature.

The painting, located in the limestone cave of Leang Karampuang in the Maros-Pangkep region of South Sulawesi, portrays three human-like figures interacting with a wild pig.

To determine its age, the team applied a novel method of laser ablation U-series (LA-U-series) analysis, to date tiny layers of calcium carbonate that had formed on top of the art.

The results revealed the underlying artwork was painted at least 51,200 years ago, making it the oldest known reliably dated cave art image in the world, and the earliest narrative art found anywhere.

The team was led by Adhi Agus Oktaviana, an Indonesian rock art specialist from the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) in Jakarta and PhD student in the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research (GCSCR).

The new LA-U-series dating method was co-developed by Professor Maxime Aubert, a specialist in archaeological science at GCSCR, and his colleague at Southern Cross University (SCU) in Lismore, Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau an expert in archaeogeochemistry in the Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group (GARG).

We have previously used the uranium-series method to date very old rock art in two parts of Indonesia, Sulawesi and Borneo, but our new LA-U-series technique is more accurate, allowing us to date the earliest calcium carbonate layers formed on the art and get closer to the point in time the art was created. It will revolutionise rock art dating.

Professor Maxime Aubert, corresponding author

School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science

Griffith University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia.

The innovative technique we've pioneered enables us to create detailed 'maps' of calcium carbonate layers. This capability empowers us to pinpoint and steer clear of regions affected by natural diagenesis processes, which stem from intricate growth histories. Consequently, our age determinations for rock art become more robust and dependable.

Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau, co-lead author

Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group

Southern Cross University, Lismore, New South Wales, Australia.

According to Oktaviana, the discovery that the Leang Karampuang painting is at least 51,200 years old has important implications for our understanding of the origin of early art.

The team used LA-U-series to re-date calcium carbonate deposits overlying a cave painting at a site in Maros-Pangkep, Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4. This painting comprises a narrative ‘scene’ depicting figures interpreted as therianthropes (part-human, part-animal beings) hunting warty pigs and dwarf buffalo and had previously been dated by the team to at least 44,000 years ago. Using the new technique, they demonstrated this artwork is some 4000 years older in minimum age at around 48,000 years.Our results are very surprising: none of the famous European Ice Age art is anywhere near as old as this, with the exception of some controversial finds in Spain, and this is the first-time rock art dates in Indonesia have ever been pushed beyond the 50,000-year mark.

Adhi Agus Oktaviana, co-lead author.

School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science

Griffith University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia.

Professor Adam Brumm from Griffith’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution (ARCHE), who co-led the study, said that the cave art from Leang Karampuang and Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4 casts new light on the great age and important role of storytelling in the history of art.

It is noteworthy that the oldest cave art we have found in Sulawesi thus far consists of recognisable scenes: that is, paintings that depict humans and animals interacting in such a way that we can infer the artist intended to communicate a narrative of some kind – a story.

Professor Adam Brumm, co-lead author

Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution,

Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Professor Brumm said this was a novel finding because the academic view of early figurative cave art has long been that it consisted of single-figure panels in which no obvious scenes were evident, and that pictorial representations of storytelling only appeared much later in the art of Europe.

The discovery by Oktaviana and the Griffith-led team therefore suggested that narrative storytelling was a crucial part of early human artistic culture in Indonesia from a very early point in time.

The study ‘Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago’ has been published in Nature.Humans have probably been telling stories for much longer than 51,200 years, but as words do not fossilise we can only go by indirect proxies like depictions of scenes in art – and the Sulawesi art is now the oldest such evidence by far that is known to archaeology.

Adhi Agus Oktaviana.

What is laser-ablated U-series (LA-U-series) dating and how does it work? Laser-ablated U-series (LA-U-series) dating is a method used to determine the age of calcium carbonate materials, such as those found in cave deposits (speleothems) and coatings on cave paintings. This technique involves analyzing the isotopic composition of uranium (U) and its decay products. Here's an overview of how it works:

Principles of U-Series Dating

How Laser-Ablated U-Series (LA-U-Series) Dating Works

- Radioactive Decay:

- Uranium (U) has several isotopes, but U-238 and U-235 are the most relevant for U-series dating.

- U-238 decays through a series of intermediate isotopes to eventually form stable lead (Pb-206).

- One of the intermediate isotopes is thorium-230 (Th-230), which is used in U-series dating.

- Uranium and Thorium in Carbonates:

- When calcium carbonate forms, it incorporates uranium but usually excludes thorium because of thorium’s insolubility in water.

- Over time, uranium-238 decays to thorium-230, increasing the Th-230 concentration in the sample.

- Age Determination:

- The ratio of Th-230 to U-238 (or U-234, another intermediate in the decay chain) in a sample indicates the time that has passed since the calcium carbonate formed, because the decay rate is well known.

Advantages of LA-U-Series Dating

- Sample Preparation:

- A small sample of calcium carbonate is selected for analysis, often from thin layers of speleothem or calcite deposits on cave walls.

- Laser Ablation:

- A laser is used to ablate (remove) tiny amounts of material from the sample’s surface. The laser focuses on specific points, vaporizing the material and transporting it to an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS).

- Laser ablation allows for precise targeting of specific areas, minimizing contamination and enabling high spatial resolution.

- Mass Spectrometry:

- The ablated material is ionized in the ICP-MS, and the isotopic composition of uranium and thorium is measured.

- The ratio of Th-230 to U-238 (or U-234) is determined from these measurements.

- Calculations and Corrections:

- The age of the sample is calculated based on the measured isotopic ratios, taking into account the known decay rates of uranium isotopes to thorium.

- Corrections may be applied for initial thorium content and potential detrital contamination.

Applications

- High Precision and Accuracy:

- The use of laser ablation allows for precise sampling and minimal contamination, leading to more accurate age determinations.

- Spatial Resolution:

- This method can analyze very small areas, which is particularly useful for heterogeneous samples or thin layers of carbonate deposits.

- Non-Destructive:

- The technique is relatively non-destructive compared to bulk sampling methods, preserving more of the original sample.

Conclusion

- Cave Paintings:

- LA-U-series dating is particularly valuable for dating calcite deposits that form over or under cave paintings, providing minimum or maximum ages for the art.

- Speleothem Formation:

- It is also used to date speleothem formations in caves, contributing to paleoclimate reconstructions and understanding geological processes.

Laser-ablated U-series dating is a sophisticated technique that leverages the natural decay of uranium to thorium to determine the age of calcium carbonate materials with high precision. By using laser ablation to precisely sample tiny areas, this method is especially effective for dating complex or delicate samples, such as those found in archaeological and paleontological contexts.

Abstract

Previous dating research indicated that the Indonesian island of Sulawesi is host to some of the oldest known rock art1,2,3. That work was based on solution uranium-series (U-series) analysis of calcite deposits overlying rock art in the limestone caves of Maros-Pangkep, South Sulawesi1,2,3. Here we use a novel application of this approach—laser-ablation U-series imaging—to re-date some of the earliest cave art in this karst area and to determine the age of stylistically similar motifs at other Maros-Pangkep sites. This method provides enhanced spatial accuracy, resulting in older minimum ages for previously dated art. We show that a hunting scene from Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, which was originally dated using the previous approach to a minimum of 43,900 thousand years ago (ka)3, has a minimum age of 50.2 ± 2.2 ka, and so is at least 4,040 years older than thought. Using the imaging approach, we also assign a minimum age of 53.5 ± 2.3 ka to a newly described cave art scene at Leang Karampuang. Painted at least 51,200 years ago, this narrative composition, which depicts human-like figures interacting with a pig, is now the earliest known surviving example of representational art, and visual storytelling, in the world3. Our findings show that figurative portrayals of anthropomorphic figures and animals have a deeper origin in the history of modern human (Homo sapiens) image-making than recognized to date, as does their representation in composed scenes.

Main

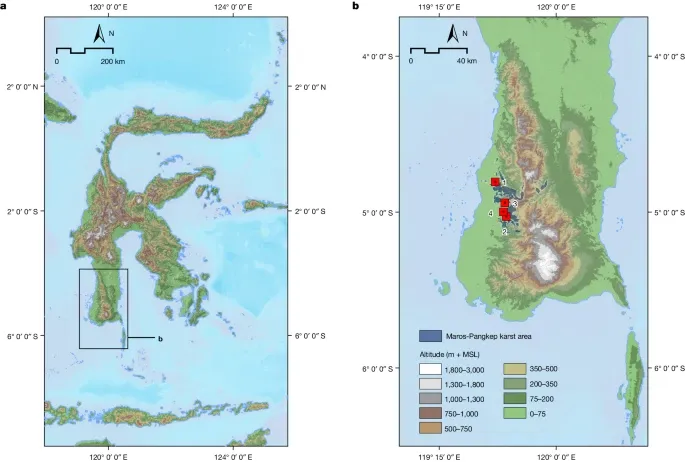

Prehistoric rock art provides important insights into past human cultures, but is typically challenging to date in an accurate and reliable manner4,5. Over the past few decades, solution-based U-series methods have been used to produce early dates for rock art in several regions, including western Europe6,7,8,9, Island Southeast Asia1,2,3,10,11 and Russia12. In Spain, a hand stencil has been dated using solution U-series analysis of overlying calcite to at least 64.8 ka, and is therefore attributed to Neanderthals9; however, dating evidence presented for this image has been questioned13,14,15,16. Up until now, the earliest evidence for figurative art had comprised a naturalistic painting of a Sulawesi warty pig (Sus celebensis) at Leang Tedongnge in Maros-Pangkep (Fig. 1), which was dated using solution U-series to a minimum of 45.5 ka (ref. 3).Thus far, only solution-based U-series methods have been used to date calcium carbonate deposits that formed in direct association with rock art. This approach involves the physical microexcavation of arbitrary layers of calcium carbonate and their chemical preparation before analysis using multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS). The technique allows for small analytical error, but has some disadvantages for dating thin calcium carbonate layers associated with rock art, especially those with complex growth history; the latter includes the coralloid speleothems (also known as ‘cave popcorn’), which are most often found in association with rock art in limestone karst caves and shelters in Indonesia1,2,3,11. Here we used a laser-ablation U-series (LA-U-series) approach to date these thin calcite accretions in association with rock art. Instead of physically microexcavating arbitrary ‘spits’ using a rotary tool, as was done in the previous approach, the laser is focussed on a polished cross-section and requires no chemical preparation. The small spot size of the laser-ablation system (typically spot diameters of 44 μm) offers several advantages over solution-based methods: (1) it is fast and cost effective; (2) it requires a much smaller sample, and is therefore less destructive; (3) the spatial resolution obtained using this method allows the detailed growth history of the speleothem to be revealed and the age of the oldest deposit closest to the pigment layer to be precisely defined, improving accuracy; (4) it can be easily and rapidly demonstrated that the calcite has not undergone remobilization of uranium (and areas exhibiting these issues can be identified and avoided), which could be problematic for U-series dating (Methods, Supplementary Information and Extended Data Table 1).Fig. 1: Map of the study area.a, The Indonesian island of Sulawesi, showing the location of the southwestern peninsula (area inside rectangle). b, South Sulawesi, with the limestone karst area of Maros-Pangkep indicated by blue shading. The locations of cave sites with dated Late Pleistocene rock art were as follows: 1, Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4; 2, Leang Karampuang; 3, Leang Tedongnge; 4, Leang Timpuseng. Map sources: GEBCO 2023 Grid; South Sulawesi karst database (Badan Lingkungan Hidup Daerah Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan; I. A. Ahmad, A. S. Hamzah). MSL, mean sea level.

Coralloid speleothems found in association with rock art often have complex internal morphologies that reflect their origin as aggregates of a cluster of cylindrical, mound-like calcite structures17, leaving overhanging features with gaps between older material that are infilled by carbonate materials of younger age. As the physical microexcavation procedure involves laterally collecting material from an arbitrary depth above the pigment layer—as opposed to sampling individual laminae—the resultant U-series age could, in some instances, be an average of the older mound material and the younger infill. Similarly, the lateral averaging of onion-like undulating layers can mix calcium carbonate material of different ages, sometimes resulting in a series of arbitrary subsamples with ages appearing not to be in chronological order. Such a complicated growth history may account for the small age reversals that are sometimes observed in previously dated samples using mechanical abrasion of arbitrary layers2,3. Here we used our LA-U-series approach to map the U-series isotopes across the surface areas of sample cross-sections. This approach enables us to understand the complex ways in which coralloid speleothems have formed, therefore enabling the analyst to identify, and avoid, small zones affected by diagenesis18.

The LA-U-series method generally provides age estimates with larger errors than the solution-based method, but it can result in genuinely older minimum ages for art as calcium carbonate material closer to the pigment layer can be analysed. This error can be improved by integrating a larger area of data; however, it can result in younger minimum ages as calcium carbonate material from later growth stages would need to be integrated. A more efficient way of minimizing this error involves slowing down the speed of the laser stage and increasing the integration time on the MC-ICP-MS, resulting in more datapoints for similar integrated areas. The trade-off is a substantial increase in the time needed to complete the analysis (Methods and Supplementary Information). We found that a spot size of 44 µm with a laser rastering speed of 21 µm s−1 (with a 2.097 s integration time) was optimal for most circumstances.

New ages for previously dated art

To demonstrate the efficiency and reliability of this technique, we re-dated what was previously the oldest known surviving pictorial narrative, a rock art scene at Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, which we had already dated to a minimum of 43.9 ka (ref. 2). At this cave site, a 4.5-m-wide panel on the rear wall comprises several figurative paintings of human-like figures interacting with Sulawesi warty pigs and dwarf bovids (anoas, Bubalus sp.) (Fig. 2). The former are depicted with material culture objects (spears and/or ropes) and some display what can be construed as attributes of non-human animals. These figures are interpreted as representations of therianthropes (composite human–animal beings)2. This enigmatic scene may represent a hunting narrative, while the prominent portrayal of therianthropic figures implies that the artwork reflects imaginative storytelling (for example, a myth)2.

We originally dated a total of four coralloid speleothems overlying animal figures on this panel to a minimum of 35.1 ka (35.7 ± 0.6 ka; sample BSP4.2), 43.9 ka (44.4 ± 0.5 ka; BSP4.3), 40.9 ka (41.1 ± 0.2 ka; BSP4.4) and 41 ka (41.3 ± 0.4 ka; BSP4.5). Using our LA-U-series method, those same speleothems and the associated artwork are now dated to a minimum of 27.6 ka (28.3 ± 0.6 ka; sample BSP4.2), 39.6 ka (43.2 ± 3.6 ka; sample BSP4.3), 39.5 ka (40.4 ± 0.9 ka; sample BSP4.4) and 48 ka (51.2 ± 2.2 ka; sample BSP4.5) (Fig. 2). Our LA-U-series approach provides either similar ages within error or older ages when compared with previous dates for the same samples (Fig. 2). The only exception is for sample BSP4.2, for which the LA-U-series data for the calcium carbonate deposits closer to the pigment layer are younger. We attribute this discrepancy to our selective avoidance of areas within the sample showing clear alteration (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 4 and Extended Data Table 1).Fig. 2: Dated rock art panel at Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4. a, Photostitched panorama of the rock art panel (using photographs enhanced using DStretch_Ire). Ther, therianthrope. b, Tracing of the dated rock art panel showing the results of LA-U-series dating. c, Transect view of the rock art sample BSP4.5 after removal from the artwork, highlighting the paint layer and the three integration zones (ROIs) and associated age calculations. d, LA-MC-ICP-MS imaging of the BSP4.5 232Th/238U isotopic activity ratio.

a, Photostitched panorama of the rock art panel (using photographs enhanced using DStretch_Ire). Ther, therianthrope. b, Tracing of the dated rock art panel showing the results of LA-U-series dating. c, Transect view of the rock art sample BSP4.5 after removal from the artwork, highlighting the paint layer and the three integration zones (ROIs) and associated age calculations. d, LA-MC-ICP-MS imaging of the BSP4.5 232Th/238U isotopic activity ratio.

The rock art scene at Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4 can now be demonstrated to be at least 4,040 years older at 48 ka. On the basis of previous results, it appears that our mechanical microsampling approach2 either fortuitously avoided areas of diagenesis or that the averaging of microexcavated arbitrary layers rendered any localized digenesis inconsequential to the overall age calculation for these layers. Again the exception is for sample BSP4.2, for which the older minimum age for solution data near the pigment layer could be attributed to localized diagenesis. Our mapping data also show clear evidence of diagenesis occurring at the surface of samples and sometimes near tiny cavities within them. The latter areas would be impossible to avoid when microexcavating arbitrary spits for solution-based U-series methods and could result in erroneous age determinations. Using the LA-U-series mapping approach, these areas of localized digenesis can easily be avoided (that is, not integrated) when calculating U-series ages from map data. Notably, for example, the 230Th/232Th activity ratios for the laser-ablation regions of integration (ROIs) (Extended Data Table 1) are substantially higher than solution data for the same samples owing to the selective avoidance of areas with higher detrital content.

Dating results for Leang Karampuang rock art

Using the LA-U-series method, we also dated another rock art scene in Maros-Pangkep—one that again portrays human-like figures interacting with an animal (Figs. 1 and 3, Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Information). This ceiling panel was discovered in 2017 at the limestone cave of Leang Karampuang (Fig. 1). It is in a poor state of preservation owing to extensive exfoliation of the limestone rock surface, a process that has erased much of the art. The presence of abundant overlying coralloid growths (and other types of speleothems) further obscures the imagery (Fig. 3). The visible elements of the scene are dominated by a large (92 × 38 cm) naturalistic red painting of a suid (most probably S. celebensis). This animal figure is represented as a pictorial outline shown in side (profile) view with an infill pattern consisting of painted strokes or lines. It is therefore consistent in style with the visual convention used to represent pigs and other animals in the dated Late Pleistocene rock art of South Sulawesi, including at Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4 (ref. 2). Other pig motifs (n = 5) are present at Leang Karampuang, but do not seem to be associated with the dated panel (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Information). In the latter, the pig is standing in a static position with its mouth partly open. At least three human-like figures (denoted H1 to H3) were depicted in close association with the pig as part of a single composition (Fig. 3). The former were portrayed using the same red-hued pigment and broadly the same stylistic convention as the pig, although they are smaller in size. At least two are arrayed in dynamic action poses near the head and face of the animal and seem to be engaged in some kind of close interaction with it. The largest human-like figure (H1, 42 × 27 cm) is represented with both arms extended; it has no legs, and it appears to be holding an item of material culture in its left hand, a rod-like object with a protuberance at both ends. The second human-like figure (H2, 28 × 25 cm) is positioned immediately in front of the pig with its head next to the snout. It also seems to have both arms extended and is holding a stick-like object of indeterminate form in its left hand, one end of which may be in contact with the pig’s throat area. The last human-like figure (H3, 35 × 5 cm) is depicted in an upside-down position with its legs facing up and splayed outwards. It also has its arms extended, with one hand reaching towards and seemingly touching the pig’s head. Pigment traces between H1 and H3 suggest that another figure may have originally been part of the scene. At least two hand stencils visible on the panel seem to be contemporary with the scene; another hand stencil, made using a darker pigment, is overlaid by the pig and was therefore produced earlier in time (Fig. 3). The actions taking place among the figures in this scene are difficult to interpret. In contrast to the dated artwork at Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, this composition involving human-like figures and an animal does not seem to explicitly depict hunting activity, nor are therianthropes obviously represented, although we cannot rule out either.We collected four coralloid speleothems, one over each of the human-like figures and one over the closely associated pig motif (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 3). Samples LK1, LK2 and LK4 directly overlay H2, H3 and H1, respectively, while LK3 directly overlays the pig image. The results of LA-U-series dating of LK1 provided a minimum age of 51.2 ka (53.5 ± 2.3 ka), whereas the same method applied to LK2, LK3 and LK4 yielded minimum ages of 18.7 ka (19.2 ± 0.5 ka), 31.9 ka (34.1 ± 2.2 ka) and 44 ka (45.9 ± 1.9 ka), respectively (Fig. 3). Thus, we can demonstrate that this rock art scene was present at Leang Karampuang at least 51.2 ka, when the oldest dated coralloid (LK1) began to form on top of figure H2.Fig. 3: Dated rock art panel at Leang Karampuang. a, Photostitched panorama of the rock art panel (with photographs enhanced using DStretch_ac_lds_cb). b, Tracing of the rock art panel showing the results of LA-U-series dating. c, Tracing of the painted scene showing the human-like figures (H1, H2 and H3) interacting with the pig. d, Transect view of the coralloid speleothem, sample LK1, removed from the rock art panel, showing the paint layer and the three integration zones (ROIs), as well as the associated age calculations. e, LA-MC-ICP-MS imaging of the LK1 232Th/238U isotopic activity ratio.

a, Photostitched panorama of the rock art panel (with photographs enhanced using DStretch_ac_lds_cb). b, Tracing of the rock art panel showing the results of LA-U-series dating. c, Tracing of the painted scene showing the human-like figures (H1, H2 and H3) interacting with the pig. d, Transect view of the coralloid speleothem, sample LK1, removed from the rock art panel, showing the paint layer and the three integration zones (ROIs), as well as the associated age calculations. e, LA-MC-ICP-MS imaging of the LK1 232Th/238U isotopic activity ratio.

Implications for the early history of art

At Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, our LA-U-series dating work shows that the panel with the figurative art and composed scene is at least several thousand years older than previously established2, with a new minimum age of 48 ka. Furthermore, our use of the same method at Leang Karampuang shows that both forms of artistic expression (naturalism and narrative) date to at least 51.2 ka in the Maros-Pangkep karsts. It is evident from these findings that the use of figurative depiction has a particularly deep antiquity in the history of early human visual culture. Presently, the earliest widely accepted evidence for image-making by our species is from Middle Stone Age southern Africa (around 100–75 ka) and comprises geometric motifs (grid-like patterns) incised on small ochre nodules19. It is therefore an open question whether the origin of figurative depiction can be traced to an artistic culture that arose in Africa after the emergence of this early tradition of producing non-representational marks, or somewhere outside it after the dispersal of H. sapiens, including in Southeast Asia.

The new Sulawesi dates also challenge two key premises in the study of Pleistocene art, both of which are based on the rich record of artistic production in Upper Palaeolithic Europe (~40–10 ka): first, that the depiction of anthropomorphs or human-like figures did not become relatively common until towards the end of the Late Pleistocene20,21; and second, that the creation of obvious narrative compositions was rare or absent in early cave art generally22,23,24.

Concerning the latter, of the three oldest dated cave art panels now known from Sulawesi, Leang Karampuang (minimum age, 51.2 ka), Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4 (minimum age, 48 ka) and Leang Tedongnge (minimum age, 45.5 ka)3 all involve figures that are grouped together in such a way as to allow an observer to infer actions taking place among them. It is possible that the Leang Tedongnge art is older; however, we were unable to redate it using the new approach, as there was no calcium carbonate material remaining (the previous method involved the use of the entire sample)3. Two panels seem to comprise pictorial representations of human–animal relationships (Leang Karampuang and Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4), while the third depicts animals (S. celebensis) that are apparently interacting with each other3. Moreover, the panel at Leang Timpuseng (minimum age, 35.3 ka) portrays a pig standing on a painted line representing the land surface1, another convention used in scenic depiction22,23,24. The use of composed scenes in cave art may have enhanced the communicative potential of this visual medium22,23,24. In contrast to single-figure depictions, the agency of the juxtaposed figures constituting a narrative scene allows a story to be told through images in a manner that does not require the producer of the art to be present to convey the narrative to an audience22,23,24. Scene-making has therefore been linked to an increase in the potential for images that persisted on rock surfaces to transmit particular narratives (such as myths) over long periods of time, especially when combined with oral traditions22,23,24. On the basis of our dating work, it now seems that depictions of anthropomorphic figures (including therianthropes) interacting with animals appear in the Late Pleistocene cave art of Sulawesi at a frequency not seen elsewhere until tens of millennia later in Europe. This implies that a rich culture of storytelling developed at an early period in the long history of H. sapiens in this region — in particular, the use of scenic representation to tell visual stories about human–animal relationships.

Oktaiana, A.A., Joannes-Boyau, R., Hakim, B. et al. Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07541-7

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

To anyone grown up enough to be interested in the truth of their own species' history, a fascinating picture of cultural and biological evolution of a species making its way out of African and into the rest of the world, is being revealed by science. And it contrasts markedly with the childish narrative made up by ignorant Bronze Age pastoralists who knew nothing of the world outside their own very limited horizons and nothing of history beyond the tales made up by their own tribal leaders - usually to justify their positions of power and authority within the tribe.

The difference between the tales in Genesis and the reality being revealed by science is such that it can't even be explained away as some sort of allegory or metaphor. There never was a magical creation of everything out of nothing 10,000 years ago; there never was a single founder couple for the human species, made by magic without ancestors and there never was a global genocide caused by a spiteful magic sky god.

Genesis is just wrong, and badly so, on every level, so can't possibly be the work of an omniscient creator god. All creationists need do is accept that their mummy and daddy were wrong, no matter how difficult they find that to believe.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.