The Megacheiran candidate: Fossil hunters strike gold with new species | YaleNews

It's another of those 'non-existent' transitional fossils days that come round several times a month, as scientists find yet another fossil which is clearly of an intermediate species between two different taxons.

Today's example is of an intermediate or stem species from which horseshoe crabs, spiders and scorpions evolved. It lived about 450 million years before there was an Earth for it to live on, according to creationists superstition, which believe Earth was created by magic as a small flat planet with a dome over it between 6 and 10,000 years ago.

The fossils in “Beecher’s Bed” in Central New York. Beecher's Trilobite Bed, located in upstate New York, is an extraordinary fossil site within the Ordovician Frankfort Shale, a rock formation dating back about 450 million years. Discovered in the late 19th century by paleaontologists Charles Beecher, it’s renowned for preserving trilobites with incredibly detailed soft tissue, a rarity in the fossil record.The fossil, Lomankus edgecombei, a Megacheirans, was found in 'fools gold' (iron pyrites) in central New York, which is a rare fossilisation process that preserves soft tissue structures in exquisite detail and is a candidate for the stem species of horseshoe crabs, spiders and scorpions. It is the only known Megacheirans to have survived beyond the Cambrian into the Ordovician by which period all the Megacheirans were thought to have gone extinct. The fossil was discovered by palaeontologists from Yale University. They have recently published their findings in Current Biology and are explained in a Yale New article by Jim Shelton.

Key Features of Beecher’s Bed:

- Exceptional Soft-Tissue Preservation: The trilobites from Beecher's Bed are fossilized in pyrite (fool’s gold), which has preserved not only their exoskeletons but also delicate, soft body parts, including legs, antennae, and gills. This unique preservation is likely due to the low-oxygen, sulfide-rich environment where the organisms were rapidly buried, preventing decay.

- Pyritization Process: The pyrite replacement occurred as iron and sulfur from the surrounding sediment reacted with the organic matter, replacing the original tissues. This rare process has left the fossils with a golden, metallic sheen, adding a striking visual aspect to their scientific value.

- Paleoecological Insights: The fossils give scientists a rare look at trilobite anatomy and offer insight into their lifestyle. For example, the presence of complex appendages and delicate structures indicates they were likely agile bottom-dwellers.

- Research Significance: Beecher’s Bed continues to be a valuable resource for studying Ordovician ecosystems, evolutionary biology, and taphonomy (the process of fossilization). It has led to a better understanding of the early marine environment and trilobite behavior.

Because of its scientific and historical importance, Beecher’s Trilobite Bed is recognized as one of the most important fossil sites in North America.

The Megacheiran candidate: Fossil hunters strike gold with new species

Ancient “gold” bug fossils, infused with pyrite, have been identified as a new species of arthropod.

Palaeontologists have identified fossils of an ancient species of bug that spent the past 450 million years covered in fool’s gold in central New York.

The new species, Lomankus edgecombei, is a distant relative of modern-day horseshoe crabs, scorpions, and spiders. It had no eyes, and its small front appendages were best suited for rooting around in dark ocean sediment, back when what is now New York state was covered by water.

Lomankus also happens to be bright gold — thanks to layers of pyrite (fool’s gold) that have crept into its remains.

And the gold color isn’t just for show. The pyrite, located in a fossil-rich area near Rome, New York, known as “Beecher’s Bed,” helped to preserve the fossils by gradually taking the place of soft-tissue features of Lomankus before they decayed.

These remarkable fossils show how rapid replacement of delicate anatomical features in pyrite before they decay, which is a signature feature of Beecher’s Bed, preserves critical evidence of the evolution of life in the oceans 450 million years ago.

Professor Derek E.G. Briggs, co-author G. Evelyn Hutchinson Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.

Briggs is co-author of a new study in Current Biology describing the new species. He is also a curator at the Yale Peabody Museum.

Briggs and his co-authors said Lomankus, which is part of an extinct group of arthropods called Megacheira, is evolutionarily significant in several ways.

Like other Megacheirans, Lomankus is an example of an arthropod with an adaptable head and specialized appendages (a scorpion’s claws and a spider’s fangs are other examples). In the case of Lomankus, its front appendages bear a trio of long, flexible, whip-like flagella — which may have been used to perceive its surroundings and detect food.

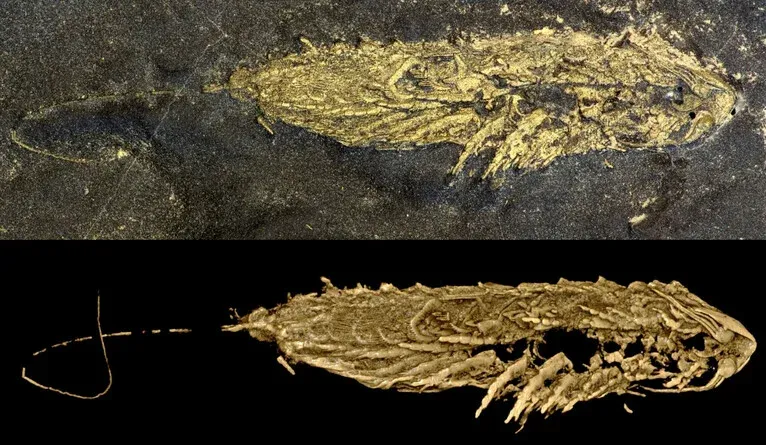

Morphology of Lomankus edgecombei reconstructed using computed tomography. The fossils are infused with pyrite (fool’s gold). In these images, the morphology of Lomankus edgecombei was reconstructed using computed tomography. The fossils are infused with pyrite (fool’s gold), causing the gold color.

Arthropods typically have one or more pairs of legs at the front of their bodies that are modified for specialized functions like sensing the environment and capturing prey. These special legs make them very adaptable, somewhat like a biological Swiss army knife.

Dr. Luke A. Parry, corresponding author

Formerly, Yale University Now Department of Earth Sciences

University of Oxford, Oxford UK.

In addition, the Lomankus fossils indicate that Megacheirans continued to evolve and diversify longer than previously thought. Lomankus is one of the only known Megacheirans to have survived past the Cambrian Period (485 to 541 million years ago) and into the Ordovician Period (443 to 485 million years ago). Paleontologists believe Megacheirans were largely extinct by the beginning of the Ordovician Period.

The new Lomankus fossils also have several ties to Yale’s paleontological efforts, going back more than a century.

The site where they were discovered, Beecher’s Bed, is named for Charles Emerson Beecher, who was head of the Yale Peabody Museum from 1899 until 1904. Beecher published classic papers on the anatomy and relationships of trilobites (one of the earliest arthropod groups) from the site, and his material was studied and expanded upon by other scientists for generations.

Briggs was one of them. His first paper on Beecher’s Bed fossils was published in 1991, and as curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Peabody in the early 2000s (and subsequently director of the museum), he arranged for Yale to lease the site for field studies until 2009.

Paleontologist Yu Liu of Yunnan University in China, co-corresponding author of the study, contacted Briggs about the new fossils from Beecher’s Bed, which he had acquired from a Chinese fossil collector. Briggs then brought in Parry, his former postdoc, with whom he was already collaborating on research about similar fossils at the Peabody.

The preservation is remarkable. The density of the pyrite contrasts with that of the mudstone in which they were buried. Their details were extracted based on computed tomography [CT] scanning, which gave us 3D images of the fossils.

Professor Derek E.G. Briggs

The new fossil specimens have been donated to the Peabody.

An exquisitely preserved stem species such as this should be an opportunity too good to be missed. for creationists to show off how disingenuous and ignorant of biology they are by waving this evidence of a transitional species aside by saying it is a fully formed species with gaps either side of it and demanding to see the 'missing links'.HighlightsSummary

- The youngest leanchoiliid arthropod described from the Late Ordovician of the USA

- Iron pyrite preservation allows high-resolution 3D reconstruction by CT scanning

- The head anatomy of leanchoiliids is resolved in unprecedented detail

The “short-great-appendage” arthropods (Megacheira), such as Leanchoilia, have featured heavily in discussions of arthropod evolution, particularly related to the head and its appendages.1,2,3,4 Megacheirans are subject to competing interpretations, either as a clade4 or a grade,5 in the stem group of Euarthropoda6 or, alternatively, Chelicerata.4 They are most diverse in Cambrian Burgess-Shale-type deposits, where the family Leanchoiliidae is represented by six genera,7,8,9,10,11,12 characterized by the presence of three distal flagella on the great appendage with a presumed sensory function. We describe the first post-Cambrian member of this family, Lomankus edgecombei gen. et sp. nov, from the Upper Ordovician (Katian) Beecher’s Trilobite Bed site of New York State—the first post-Cambrian megacheiran with the exception of the Silurian and Devonian Enaliktidae. Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanning reveals the morphology of the short great appendage with elongate flagella, four biramous cephalic limbs, 11 trunk segments with biramous limbs and dorsal tergites, and an elongate telson unique within Leanchoiliidae. The great appendage is also unique: the long endites that bear the flagella in other leanchoiliids are absent (or at least greatly reduced) and each flagellum appears to attach directly to an individual podomere, suggesting a sensory rather than a raptorial function. The remarkable preservation of a well-developed ventral plate (epistome-labrum complex) anterior of the mouth reinforces a deutocerebral origin2,13 of the short great appendages. Lomankus edgecombei unveils the three-dimensional (3D) head morphology of leanchoiliids in unparalleled detail and demonstrates that these iconic fossil arthropods ranged into dysaerobic environments in the Ordovician, where Lomankus occupied a deposit-feeding niche.

Figure 1 Lomankus edgecombei from the Beecher’s Trilobite Bed site of New York State

Figure 1 Lomankus edgecombei from the Beecher’s Trilobite Bed site of New York State

- Ventral view, YPM IP 256612, RTI image using normal unsharp masking.

- Ventral view, YPM IP 256613, RTI image using diffuse gain.

- Right lateral view, YPM IP 236743, RTI image using diffuse gain.

- Right lateral view, partially exposed, YPM IP 516237, RTI image using diffuse gain. See Figure S1 for illustration of the counterpart.

- Normal visualization reflectance transformation image showing tergites and trunk limbs, YPM IP 516237.

- Left lateral view, incomplete anteriorly, YPM IP236744. hs, headshield; lga, left great appendage; rga, right great appendage; tn, tergite number n; te, telson.

Figure 2 Morphology of Lomankus edgecombei reconstructed using computed tomography(A and B) YPM IP 256613. (A) Ventral and (B) dorsal view.

Figure 2 Morphology of Lomankus edgecombei reconstructed using computed tomography(A and B) YPM IP 256613. (A) Ventral and (B) dorsal view.

(C–G) YPM IP 256612. (C) Ventral and (D) dorsal view; (E) great appendages; (F) head appendages 2–5; (G) posterior trunk appendages—boxed region in (C) shows location.

(H) Close-up of the terminal claw and flanking setae of endopod 9.

(I–M) YPM IP 236743. (I) Dorsolateral and (J) ventrolateral view; (K) great appendages; (L) left head appendages 2 and 3; (M) trunk appendages 1 and 2. en, endopod; ex, exopod; hs, headshield; lga, left great appendage; lta, left trunk appendage; rga, right great appendage; se, terminal setae; pm, podomere; tn, tergite number n; ts, telson. Arrowheads in (G) identify the position of exites.

See also Figure S1.

Figure 3 Morphology of the head region and great appendage of Lomankus edgecombei, phylogeny, and life reconstruction

Figure 3 Morphology of the head region and great appendage of Lomankus edgecombei, phylogeny, and life reconstruction

(A–C) YPM IP 236743. (A) Right lateral view, RTI image using diffuse gain rendering; (B and C) CT reconstruction, ventrolateral view.

(D–F) YPM IP 256612. (D) Ventral view, RTI image using diffuse gain rendering; (E and F), CT reconstruction, ventral view.

(G) YPM IP 516237, CT reconstruction, left lateral view.

(H and I) YPM IP 256613, ventral view.

(J and K) YPM IP 256612, great appendage. (J) Ventral view of great appendage, RTI image using diffuse gain rendering; (K) CT reconstruction of great appendage, ventral view.

(L) YPM IP 516237, CT reconstruction of great appendage, left lateral view.

(M) Bayesian phylogeny based on a morphological dataset of 283 characters and 87 taxa. Majority rules consensus tree of analysis performed under the mki + gamma model using MrBayes 3.2.7. Numbers at nodes are posterior probabilities and branch lengths, and scale bars are in units of expected number of substitutions per site. Silhouettes from Phylopic (see acknowledgments for credits) except for Lomankus edgecombei by L.A. Parry.

(N) Life reconstruction of Lomankus edgecombei by Xiaodong Wang. lan, left appendage n; lga, left great appendage; os, ocular sclerite; ran, right appendage n; rga, right great appendage; vp, ventral plate.

See also Figures S2 and S3.Parry, Luke A.; Briggs, Derek E.G.; Ran, Ruixin; O’Flynn, Robert J.; Mai, Huijuan; Clark, Elizabeth G.; Liu, Yu

A pyritized Ordovician leanchoiliid arthropod

Current Biology (2024) DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.013

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by Elsevier Inc. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

But they can always scuttle off when asked what they would expect the stem species of spiders, scorpions and horseshoe crabs from about 450 million years to look like, or why they would expect it not to be a fully formed species.

This should also be a cue to bear false witness against the palaeontologists and claim the either forged the fossil of faked the age by using flawed geochronology to give them the age they wanted, without a single shred of evidence to support the accusation.

Refuting Creationism: Why Creationism Fails In Both Its Science And Its Theology

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.