Humanity’s oldest known cave art has been discovered in Sulawesi.

There's nothing quite like leaving a message behind to tell future generations that you were here.

Creationists, of course, have a message from about 5,000 years ago telling them that there were ignorant Bronze Age storytellers living in the Middle East — but sadly the only truth in their stories was the one they didn’t explicitly state: that they were making things up to explain what they didn’t know, which meant a great many stories to invent. They couldn’t have guessed, of course, that their tales would later be written down, bound up in a book, and then proclaimed to be the inerrant word of a creator god; otherwise they might have made more of an effort to get it right, or at least admitted they didn’t know. As it is, all we really learn from them is just how ignorant they were, and how vivid their imaginations must have been.

To be fair, it may not have been their intention to mislead and misinform, but that has been the result — mostly, it has to be said, through the fault of those who later declared their tales to be the authentic word of a god, because that conveniently suited their political agenda.

People living much earlier, on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, left a much clearer and more honest message in the form of cave art, and particularly hand stencils. All they really say is, “Hi there! I was here!” — with no attempt to elevate themselves to a special status or claim to know things they didn’t know. Where they depicted the animals around them, they showed them just as they saw them: wild and free.

This cave art, which precedes the celebrated art of the French and Spanish caves by tens of thousands of years, has now been identified as the oldest known cave art, telling an unambiguous story of people living there around 70,000 years ago — long before anatomically modern humans made their presence felt in Western Eurasia. The discovery and the methods used to date the art were published in Nature, in a paper that marks a defining moment in our understanding of early symbolic behaviour.

Four of the researchers — Maxime Aubert, Professor of Archaeological Science, Griffith University; Adam Brumm, Professor of Archaeology, Griffith University; Adhi Oktaviana, Research Centre of Archeometry, Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN), Jakarta, Indonesia; and Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Professor of Geochronology and Geochemistry, Southern Cross University, New South Wales, Australia — have also written an article in The Conversation that explains the significance of the find in accessible terms. Their piece is reprinted here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Humanity’s oldest known cave art has been discovered in Sulawesi

Supplied

When we think of the world’s oldest art, Europe usually comes to mind, with famous cave paintings in France and Spain often seen as evidence this was the birthplace of symbolic human culture. But new evidence from Indonesia dramatically reshapes this picture.

Our research, published today in the journal Nature, reveals people living in what is now eastern Indonesia were producing rock art significantly earlier than previously demonstrated.

These artists were not only among the world’s first image-makers, they were also likely part of the population that would eventually give rise to the ancestors of Indigenous Australians and Papuans.

A hand stencil from deep time

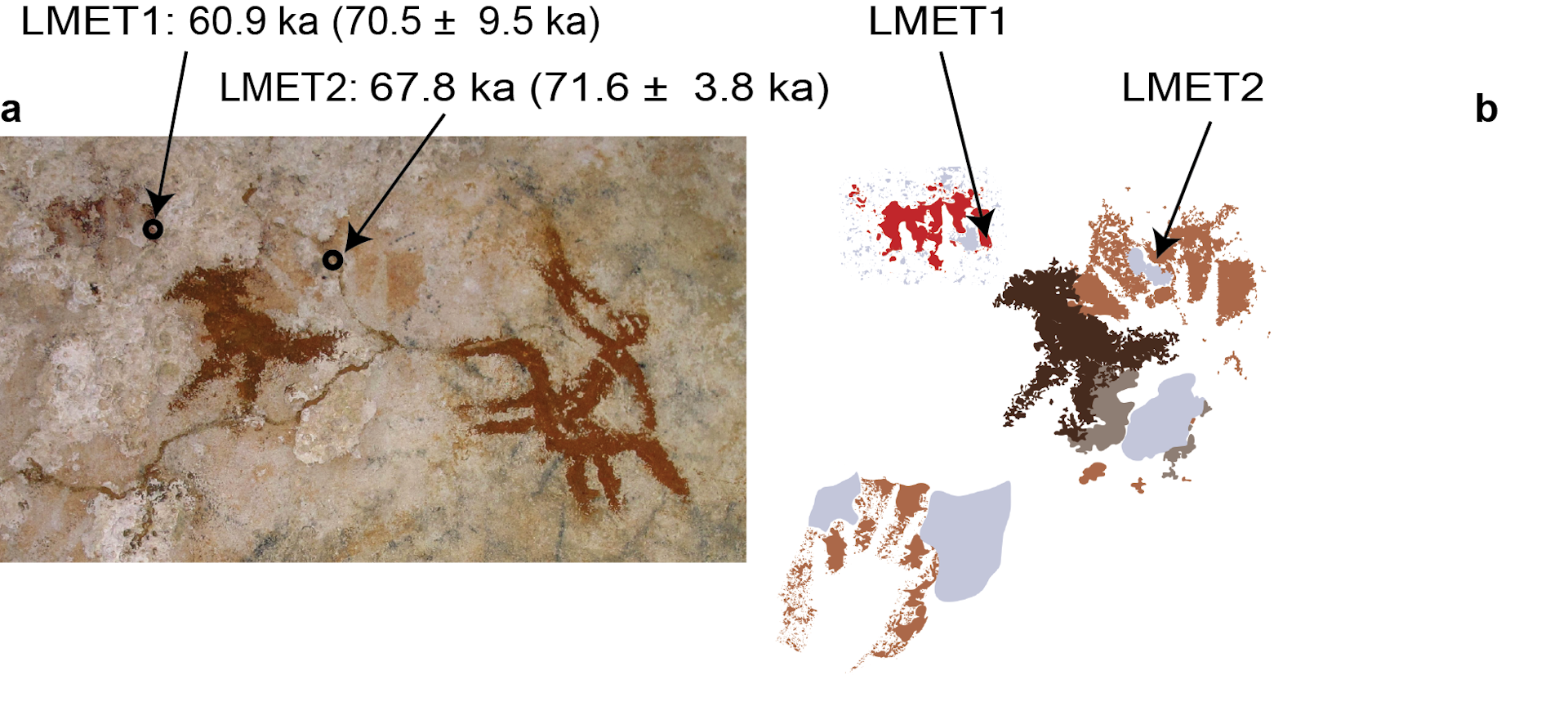

The discovery comes from limestone caves on the island of Sulawesi. Here, faint red hand stencils, created by blowing pigment over a hand pressed against the rock, are visible on cave walls beneath layers of mineral deposits.

By analysing very small amounts of uranium in the mineral layers, we could work out when those layers formed. Because the minerals formed on top of the paintings, they tell us the youngest possible age of the art underneath.

In some cases, when paintings were made on top of mineral layers, these can also show the oldest possible age of the images.

One hand stencil was dated to at least 67,800 years ago, making it the oldest securely dated cave art ever found anywhere in the world.

This is at least 15,000 years older than the rock art we had previously dated in this region, and more than 30,000 years older than the oldest cave art found in France. It shows humans were making cave art images much earlier than we once believed.

Photograph of the dated hand stencils (a) and digital tracing (b); ka stands for ‘thousand years ago’.

Supplied

Altering images of human hands in this manner may have had a symbolic meaning, possibly connected to this ancient society’s understanding of human-animal relations.

In earlier research in Sulawesi, we found images of human figures with bird heads and other animal features, dated to at least 48,000 years ago. Together, these discoveries suggest that early peoples in this region had complex ideas about humans, animals and identity far back in time.

Not a one-off moment of creativity

The dating shows these caves were used for painting over an extraordinarily long period. Paintings were produced repeatedly, continuing until around the Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago – the peak of the most recent ice age.

After a long gap, the caves were painted again by Indonesia’s first farmers, the Austronesian-speaking peoples, who arrived in the region about 4,000 years ago and added new imagery over the much older ice age paintings.

This long sequence shows that symbolic expression was not a brief or isolated innovation. Instead, it was a durable cultural tradition maintained by generations of people living in Wallacea, the island zone separating mainland Asia from Australia and New Guinea.

What this tells us about the first Australians

The implications go well beyond art history.

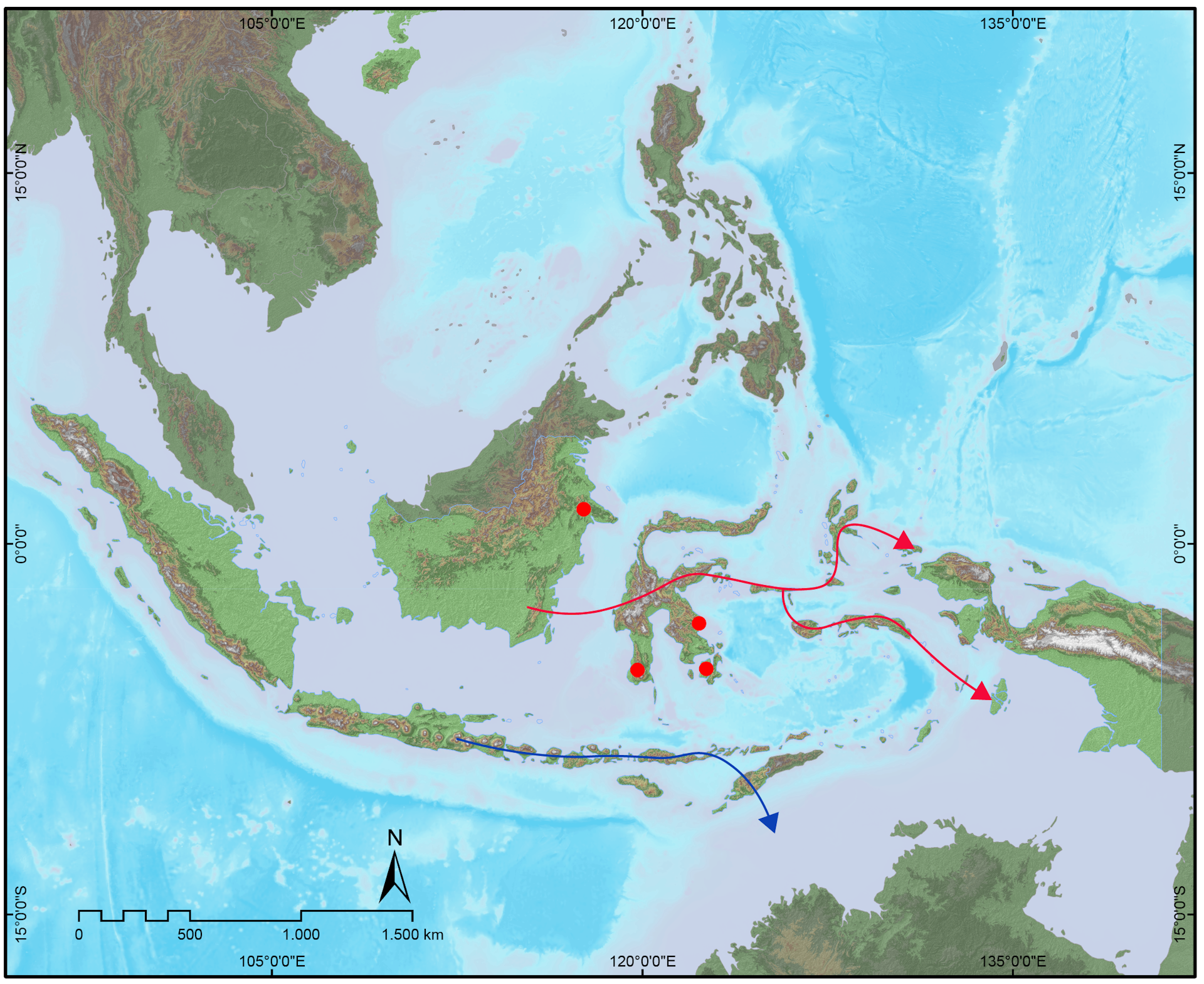

Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests modern humans reached the ancient continent of Sahul, the combined landmass of Australia and New Guinea, by around 65,000 to 60,000 years ago.

Getting there required deliberate ocean crossings, representing the earliest known long-distance sea voyages undertaken by our species.

Researchers have proposed two main migration routes into Sahul. A northern route would have taken people from mainland Southeast Asia through Borneo and Sulawesi, before crossing onward to Papua and Australia. A southern route would have passed through Sumatra and Java, then across the Lesser Sunda Islands, including Timor, before reaching north-western Australia.

The proposed modern human migration routes to Australia/New Guinea; the northern route is delineated by the red arrows, and the southern route is delineated by the blue arrow. The red dots represent the areas with dated Pleistocene rock art.

Supplied

In other words, the people who made these hand stencils in the caves of Sulawesi were very likely part of the population that would later cross the sea and become the ancestors of Indigenous Australians.

Rethinking where culture began

The findings add to a growing body of evidence showing that early human creativity did not emerge in a single place, nor was it confined to ice age Europe.

Instead, symbolic behaviour, including art, storytelling, and the marking of place and identity, was already well established in Southeast Asia as humans spread across the world.

This suggests that the first populations to reach Australia carried with them long-standing cultural traditions, including sophisticated forms of symbolic expression whose deeper roots most probably lie in Africa.

The discovery raises an obvious question. If such ancient art exists in Sulawesi, how much more remains to be found?

Large parts of Indonesia and neighbouring islands remain archaeologically unexplored. If our results are any guide, evidence for equally ancient, or even older, cultural traditions may still be waiting on cave walls across the region.

As we continue to search, one thing is already clear. The story of human creativity is far older, richer and more geographically diverse than we once imagined.

The research on early rock art in Sulawesi has been featured in a documentary film, Sulawesi l'île des premières images produced by ARTE and released in Europe today.

Maxime Aubert, Professor of Archaeological Science, Griffith University; Adam Brumm, Professor of Archaeology, Griffith University; Adhi Oktaviana, Research Centre of Archeometry, Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN), and Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Professor in Geochronology and Geochemistry, Southern Cross University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Publication:

For creationists, this discovery presents the familiar problem that reality stubbornly refuses to conform to their Bronze Age mythology. Hand stencils and animal depictions made around 70,000 years ago, on the far side of the world, do not sit comfortably alongside the claim that the universe, Earth, and all life were created only a few thousand years ago. Nor can they be waved away as some sort of geological prank, a dating “error,” or a remnant of a fictional global flood. They are there, in the rock, where people left them, and they have been dated using well-established physical methods that creationists happily rely on in every other area of modern technology.

What is particularly awkward for Intelligent Design and creationist narratives is that the researchers have no difficulty whatsoever fitting this discovery into an evolutionary framework. On the contrary, the findings make perfect sense in terms of the gradual emergence of symbolic behaviour, artistic expression, and cultural transmission among early human populations. There is no need to invoke a sudden burst of divinely gifted creativity, nor any mysterious “special creation” of cognitive abilities. What we see instead is continuity: humans behaving like humans, leaving marks of their presence, and expressing their relationship with the world around them.

This cave art also reinforces a point that creationists consistently try to avoid: that modern humans did not suddenly appear, fully formed and fully enlightened, at some arbitrary moment in the recent past. The archaeological and genetic evidence shows a long, complex history of human evolution, dispersal, and cultural development stretching back tens of thousands of years. Sulawesi now joins a growing list of sites that demonstrate just how deep those roots really go — and how provincial and parochial the biblical timeline truly is.

As so often, the real story here is not one of scientists being “confounded” or forced to abandon evolution, but of scientists extending and refining our understanding of the past. The authors of the *Nature* paper are not struggling to shoehorn awkward data into a failing theory; they are doing exactly what science is supposed to do — following the evidence wherever it leads. And once again, that evidence leads decisively away from creationist fantasy and firmly towards a world shaped by deep time, human evolution, and the ordinary, cumulative processes of nature.

In short, while Bronze Age storytellers left us myths and cosmologies that collapse on contact with reality, the people of Sulawesi left us something far more honest: a simple record of their existence, written in stone. And unlike the Bible’s creation stories, that record turns out to be not only meaningful, but demonstrably true.

Advertisement

All titles available in paperback, hardcover, ebook for Kindle and audio format.

Prices correct at time of publication. for current prices.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.