Oldest DNA from South Africa decoded to date | Max-Planck-Gesellschaft

Just as creationism's legendary creator god was creating a small flat planet with a dome over it in the Middle East, there were modern humans living (or rather dying) in South Africa.

A team of scientists led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and including palaeoanthropologists from University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, have now succeeded in reconstructing the genomes from the remains of 13 individuals who died between 1,300 and 10,000 years ago, including the oldest human genome from South Africa to date.

If the creation myth had any element of truth in it, humans would have radiated from the legendary founder couple to form a thriving community living in a rock shelter in South Africa's Cape Province. Moreover, the evidence now shows that these people were isolated from the rest of humanity for many thousands of years.

What information do you have about modern human groups and cultures from the South African Cape area, 10,000 years ago? Around 10,000 years ago, during the Late Stone Age, the region now known as the South African Cape was inhabited by indigenous hunter-gatherer groups, ancestral to the San people (also known as Bushmen). These early inhabitants were part of broader cultural developments across southern Africa, and their lives were deeply connected to the unique environment of the Cape.The significance of the find, apart from the usual casual and unintentional refutation of creationism that is the norm with most scientific discoveries, is that it suggests a prolonged period of relative isolation of a southern African population, so the genome of the oldest remains show a close kinship with the San and Khoekhoe groups living in the same region today. This changed only about 1,200 years ago with the arrival of newcomers from the north, bringing a new pastoralist culture and new languages.

Here are some key aspects of these groups:

- Culture and Way of Life

- Hunter-Gatherers: These early groups relied on hunting, fishing, and foraging for their subsistence. They hunted a variety of game, including antelope, small mammals, and birds, using spears, bows and arrows, and snares.

- Gathering: Plants, fruits, nuts, and roots were an important part of their diet, and the fynbos vegetation of the Cape provided a rich source of edible plants.

- Coastal Resources: Groups near the coast harvested marine resources like shellfish, fish, and seals, leaving behind shell middens, large mounds of discarded shells and bones, that are still found in the region today.

- Technology

- Stone Tools: These people used a range of finely crafted stone tools, characteristic of the Later Stone Age in southern Africa. These included microliths, small stone flakes used as spear tips, scrapers, and blades.

- Bone and Wood Tools: Besides stone, they made use of organic materials like bone, wood, and plant fibers to craft tools, including fishing equipment and digging sticks.

- Art and Symbolism

- Rock Art: The San are famous for their rock art, some of which dates back thousands of years. These paintings, often found in caves and rock shelters, depict animals, human figures, and shamanistic rituals, and they provide insights into their spiritual beliefs and social practices.

- Spirituality: Rock art and ethnographic evidence suggest a strong connection to shamanistic practices. The San believed in a spiritual world, with shamans acting as intermediaries between humans and supernatural forces during healing rituals and trance dances.

- Social Structure

- Small, Mobile Bands: These early groups likely lived in small, mobile bands or clans. They would move seasonally to access different resources, such as water, game, and plant foods.

- Egalitarian Society: Like the historic San groups of the 19th and 20th centuries, these hunter-gatherers likely had relatively egalitarian social structures, with decision-making shared among adult members of the group. Leadership was temporary and based on skill rather than inheritance or wealth.

- Environmental Adaptation

- Fynbos Biome: The Cape area’s unique fynbos biome, characterized by Mediterranean-type shrubland and heathland, shaped the food resources and survival strategies of these groups. Their knowledge of the local flora, especially plants used for food and medicine, was extensive.

- Climate and Migration: The end of the Pleistocene and the early Holocene brought changes in climate, which may have influenced the movements and settlement patterns of these groups. As the ice age ended, rising sea levels altered the coastline, impacting coastal resources.

- Cultural Continuity

- Ancestral San: These groups are thought to be the ancestors of the San people, who have lived in southern Africa for tens of thousands of years. Despite significant changes over millennia, the San maintained a hunter-gatherer way of life in the region until relatively recent times, when they were largely displaced by Bantu-speaking groups and European settlers.

Although there are no written records from 10,000 years ago, archaeological evidence, rock art, and ethnographic studies of later San groups provide a window into the life and culture of these ancient inhabitants of the South African Cape.

Do you have any information about the Oakhurst rock shelter in particular?

The Oakhurst rock shelter is an important archaeological site located in the southern Cape region of South Africa, and it provides significant insights into the Later Stone Age populations in the region, dating back thousands of years. The site is particularly noted for the so-called "Oakhurst Culture," which dates to around 10,000 to 5,000 years ago.

Here are some key features of the Oakhurst rock shelter:

- Chronology and Occupation

- The Oakhurst rock shelter has yielded evidence of human occupation during the Late Stone Age, approximately 10,000 years ago. Excavations have revealed a long sequence of human activity, with various layers providing a glimpse into the changing lifestyles and technologies of these early groups.

- The site is associated with the Oakhurst Complex, a cultural and technological tradition that is part of the broader Later Stone Age of southern Africa.

- Stone Tools

- Oakhurst Industry: The stone tools found at Oakhurst rock shelter belong to what is known as the Oakhurst Industry. This industry is characterized by relatively large stone artifacts, including scrapers and flakes. These tools were likely used for various purposes, including hunting, butchery, and preparing hides.

- The tools are larger compared to later technologies in the Later Stone Age, such as the microlithic Wilton Industry. This suggests that the Oakhurst people may have been less specialized in their tool production, or that their subsistence strategies involved larger game or different tasks.

- Subsistence and Diet

- The remains of fauna found at the site suggest that the inhabitants of Oakhurst were hunter-gatherers who relied on a variety of animals for food, including large game like antelope, as well as smaller animals and birds.

- Marine Resources: Oakhurst is located near the coast, and the presence of shell middens indicates that the people also made use of marine resources like shellfish and fish. These coastal resources were a crucial part of their diet, especially during periods when terrestrial resources were scarce.

- Plant Foods: Like many hunter-gatherer societies, the people of Oakhurst probably had extensive knowledge of the local flora, gathering edible plants, roots, fruits, and nuts. The nearby fynbos vegetation, rich in diverse plant species, would have provided ample plant-based food.

- Cultural and Social Aspects

- Burials: Excavations at Oakhurst rock shelter have uncovered human burials, which offer some insights into the mortuary practices of these people. Some burials were found with grave goods, such as ochre and shell beads, which may have had symbolic or ritual significance.

- Social Structure: Based on comparisons with more recent hunter-gatherer societies, it is believed that the Oakhurst people likely lived in small, mobile bands. These groups were probably organized along egalitarian lines, with shared decision-making and leadership based on skill rather than wealth or inheritance.

- Environmental Adaptation

- Mediterranean Climate: The Oakhurst rock shelter is located within the Mediterranean-type climate of the Cape, with hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. The people who lived there adapted to this environment by exploiting a variety of ecological niches, including coastal, woodland, and riverine environments.

- Seasonal Movements: It is likely that the Oakhurst groups moved seasonally between the coast and the interior, depending on the availability of resources. Coastal areas would have been particularly important during times of low inland resource availability, as they provided a consistent source of food from the ocean.

- Rock Art

- While Oakhurst is not primarily known for its rock art, the broader region of the southern Cape is rich in San rock art, depicting animals, humans, and spiritual or shamanistic scenes. This art is thought to reflect the worldview and belief systems of the people, who likely practiced shamanistic rituals involving trance states and communication with the spiritual world.

- Archaeological Significance

- Oakhurst rock shelter has been studied extensively by archaeologists because of its well-preserved stratigraphy, which provides a continuous record of human occupation and environmental change over thousands of years. The site has been pivotal in understanding the transition from larger, less specialized stone tools to the microlithic technologies of later periods, such as the Wilton Industry.

- Its location within the southern Cape’s complex landscape of coastal, fynbos, and riverine environments makes it an ideal site for studying how humans adapted to diverse ecological zones.

The findings at Oakhurst rock shelter contribute significantly to our understanding of the hunter-gatherer societies that lived in southern Africa during the Late Stone Age. They offer a window into the lives, technologies, and survival strategies of early humans as they adapted to changing environments in the region.

The team of palaeoarchaeologists who pulled off this feat of DNA recovery and reconstruction have just published their findings in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution and announced it in a Max Planck Institute News release:

Oldest DNA from South Africa decoded to date

10,000-year-old human genome are genetically similar to those of ethnic groups living in the region today

Ancient DNA has provided spectacular insights into human history, particularly in Europe and Asia, where researchers have reconstructed the genomes of thousands of people. However, fewer than two dozen ancient genomes have been recovered from southern Africa - specifically Botswana, South Africa and Zambia - which has some of the world's earliest evidence of modern humans, with the oldest genomes dating back around 2,000 years.

A team of researchers from the University of Cape Town (South Africa) and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig (Germany) have analysed human remains from the Oakhurst rock shelter in southernmost Africa and reconstructed the genomes of thirteen individuals, who died between 1,300 and 10,000 years ago, including the oldest human genome from South Africa to date.

Oakhurst rock shelter is an ideal site to study human history, as it contained more than 40 human graves and preserved layers of human artefacts, such as stone tools, going back 12,000 years. Sites like this are rare in South Africa, and Oakhurst has allowed a better understanding of local population movements and relationships across the landscape over nearly 9,000 years.

Professor Victoria Gibbon, co-senior author

Professor of Biological Anthropology

University of Cape Town

Cape Town, South Africa.

Long history of genetic stability in southernmost Africa

The successful genetic sequencing of thirteen individuals from the site was not without its challenges, as Stephan Schiffels, co-senior author of the study, explains:

Such ancient and poorly preserved DNA is quite difficult to sequence, and it took several attempts using different technologies and laboratory protocols to extract and process the DNA.

Stephan Schiffels, co-senior author

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Department of Archaeogenetics

Leipzig, Germany.

The ancient genomes represent a time series from 10,000 to 1,300 years ago, providing a unique opportunity to study human migrations through time and the relationship to the diverse groups of people living in the region today. A key finding was that the oldest genomes from the Oakhurst rock shelter are genetically quite similar to San and Khoekhoe groups living in the same region today. This came as a surprise, as Joscha Gretzinger, lead author of the study, says:

Similar studies from Europe have revealed a history of large-scale genetic changes due to human movements over the last 10,000 years. These new results from southernmost Africa are quite different, and suggest a long history of relative genetic stability.

Joscha Gretzinger, lead author

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Department of Archaeogenetics

Leipzig, Germany.

This only changed around 1,200 years ago, when newcomers arrived and introduced pastoralism, agriculture and new languages to the region and began interacting with local hunter-gatherer groups.

In one of the most culturally, linguistically and genetically diverse regions of the world, the new study shows that South Africa’s rich archaeological record is becoming increasingly accessible to archaeogenetics, providing new insights into human history and past demography.

Original publicationJoscha Gretzinger, Victoria E. Gibbon, Sandra E. Penske, Judith C. Sealy, Adam B. Rohrlach, Domingo C. Salazar-García, Johannes Krause & Stephan Schiffels

9,000 years of genetic continuity in southernmost Africa demonstrated at Oakhurst rockshelter

Nature Ecology & Evolution, 19 September 2024, DOI: 10.1038/s41559-024-02532-3

AbstractTo anyone not afraid of looking at the objective evidence presented here, it will be quite obvious that the San people of southern Africa could not have diversified from the rest of the human population of Earth, then remained isolated for the best part of 10,000 years and yet have more genetic diversity than similar Late Stone Age hunter-gatherer people in Eurasia and the Americas, all in the space of the 10,000 years that creationists mythology says there have been humans on Earth.

Southern Africa has one of the longest records of fossil hominins and harbours the largest human genetic diversity in the world. Yet, despite its relevance for human origins and spread around the globe, the formation and processes of its gene pool in the past are still largely unknown. Here, we present a time transect of genome-wide sequences from nine individuals recovered from a single site in South Africa, Oakhurst Rockshelter. Spanning the whole Holocene, the ancient DNA of these individuals allows us to reconstruct the demographic trajectories of the indigenous San population and their ancestors during the last 10,000 years. We show that, in contrast to most regions around the world, the population history of southernmost Africa was not characterized by several waves of migration, replacement and admixture but by long-lasting genetic continuity from the early Holocene to the end of the Later Stone Age. Although the advent of pastoralism and farming substantially transformed the gene pool in most parts of southern Africa after 1,300 bp, we demonstrate using allele-frequency and identity-by-descent segment-based methods that the ‡Khomani San and Karretjiemense from South Africa still show direct signs of relatedness to the Oakhurst hunter-gatherers, a pattern obscured by recent, extensive non-Southern African admixture. Yet, some southern San in South Africa still preserve this ancient, Pleistocene-derived genetic signature, extending the period of genetic continuity until today.

Main

Southern African populations today harbour genetic variation that traces deep human population history1,2, reflected also in the archaeological record with fossils of archaic Homo sapiens dating back to 260 thousand years ago (ka) before present (bp) (uncalibrated) and evidence for the presence of anatomically modern humans in South Africa from at least ~120 ka bp onwards3,4. While genetic investigations have extensively explored the significance of southern African population structure in human evolution, there is a noticeable gap in our understanding of the more recent demographic trajectories during the Holocene (the last 11,700 years), which remain relatively understudied genetically.

During the Holocene, major transformations in lithic industries and subsistence practices probably also reflect demographic shifts5,6. In the last 2,000 years, the spread of pastoralism and farming have resulted in repeated admixture events visible in genetic complexity in both ancient and contemporary populations1,2,7,8. First, the spread of herders contributed northeast African, Levantine-enriched ancestry to the genetic make-up of southern African hunter-gatherers2. Second, the influx of farmers closely related to present-day Bantu-language speakers introduced western African ancestry to San and Khoe populations2. Consequently, all contemporary San and Khoe groups exhibit at least 9% genetic admixture from non-San sources outside modern-day South Africa, Namibia and Botswana1,2,7,8, obscuring the population structures of the Later Stone Age (LSA) San population. To provide insights into early Holocene San population structure, we sampled and recovered genome-wide data from a series of individuals unearthed from the Oakhurst rockshelter in South Africa, offering a chronological spectrum spanning most of the Holocene.

Oakhurst rockshelter is located close to George in southernmost Africa, ~7 km from the coast (Fig. 1a). Excavated in the first half of the twentieth century9, it is especially noteworthy for its substantial accumulation of deposit that spans 12,000 years. Its Early Holocene macrolithic stone artefact assemblage is characteristic of the period, similar to those found at many sites across South Africa and is today regarded as a distinctive technocomplex termed the ‘Oakhurst Complex’, named after the site5,6,10,11,12,13. At ~8,000 bp, the lithics change to microlithic ‘Wilton’ assemblages which persist through the Middle and Late Holocene, albeit with some temporal shifts, notably the addition of ceramics in the last 2,000 years (refs. 6,9,14,15). The site also preserves the complete and partial burials of 46 juvenile and adult individuals, spanning the complete period of occupation of the site16,17 and providing a valuable resource for the study of LSA San population structure. Here, we present genome-wide data from 13 individuals, including the oldest DNA from South Africa, dating back to ~10,000 years (calibrated) cal bp.

Fig. 1: Population structure in present-day southern Africa. a, Approximate locations of present-day populations and ancient individuals mentioned in the article. Present-day populations are coloured according to linguistic affiliation, as indicated in the legend. b, PCA on 212,000 SNPs with ancient individuals projected onto PC1 and PC2. Shown are the positions of each individual along the first and second axes of genetic variation, with symbols denoting the individual's population and linguistic affiliation using the same colour coding as in a.

a, Approximate locations of present-day populations and ancient individuals mentioned in the article. Present-day populations are coloured according to linguistic affiliation, as indicated in the legend. b, PCA on 212,000 SNPs with ancient individuals projected onto PC1 and PC2. Shown are the positions of each individual along the first and second axes of genetic variation, with symbols denoting the individual's population and linguistic affiliation using the same colour coding as in a.

[…]

Discussion

The question of population continuity or discontinuity during the LSA of southern Africa has been the focus of anthropological research for well over a century. Archaeogenetic research of the last two decades has revealed that the Holocene demographic histories of Stone Age Europe39,65,66,67,68,69,70,71, Asia43,72,73,74,75,76,77 and North Africa78,79,80 were characterized by several episodes of large-scale migrations, either in the form of admixture with newcomers or by total replacement of the established inhabitants. While these biological transformations modified the genetic make-up of the local populations, they were also vectors for technological innovation, such as the introduction of new technologies, raw material uses or subsistence strategies. In contrast, for South Africa, we demonstrate that the local gene pool was characterized by a prolonged period of genetic continuity with no (detectable) gene flow from outside southern Africa. The earliest individual in our study that yielded aDNA showed a genetic make-up indistinguishable from the later inhabitants of Oakhurst rockshelter, suggesting that this local ‘southern’ San gene pool was formed more than 10,000 years ago and remained isolated from admixture with neighbouring ‘central’ and ‘northern’ San populations7,8,26,27,28,29 or with more distant sources to the northeast, which admixed with San groups in Malawi and Tanzania2.

Consequently, the sequence of cultural change at Oakhurst, for example from the Oakhurst to Wilton technocomplexes6,9,14,15, appears to result from local development initiated by the indigenous inhabitants14, highlighting the role of in situ innovations followed by acculturation. Our data also demonstrate that subtle fluctuations in the craniofacial size of South African LSA coastal inhabitants81,82 (for example, between 4,000 and 3,000 bp) were not the product of genetic discontinuity but probably related to changes in environmental factors or population size81,82,83. Yet, we highlight that the inhabitants of Oakhurst were not a small, bottlenecked population. Genomic measurements of diversity indicate a degree of genetic variation comparable to other African hunter-gatherer populations and higher than Stone Age foragers from Europe or America. Furthermore, the current resolution of our methods and limited reference dataset in sub-Saharan Africa restricts our ability to detect subtle changes in group size or small-scale immigration of people from within southern Africa. However, our data are congruent with a population in reproductive isolation from other San (and non-San) populations over the whole period of occupation of the site.

This period of ~9,000 years of genetic continuity ends rather abruptly in the migration events which introduced East and West African-related ancestry to South Africa, accompanied by the spread of herding and farming1,2,7,8. On the basis of present available data, it appears that non-southern African ancestry reached the southernmost parts of South Africa only after 1,300 cal bp. There is, however, abundant archaeological evidence of marked changes in subsistence and settlement patterns among coastal and near-coastal communities in this region from ~2,000 cal bp. These changes have previously been interpreted as resulting from the disruption of hunter-gatherer communities by the emergence of herding84,85,86,87. Notably, a similar temporal discrepancy was observed during the Mesolithic–Neolithic translation in Europe, where the admixture between hunter-gatherers and incoming farmers postdates the emergence of agriculture by almost 2,000 years (ref. 88). This indicates that hunter-gatherers and farmers resided in close geographic proximity for a considerable time before mixing88 and demonstrates that migration can precede any subsequent population admixture substantially. Alternatively, the practice of pastoralism may have spread to Southern Africa through a process of cultural diffusion in advance of substantial population expansion89,90, explaining the absence of any East African-related ancestry in South Africa before 1,300 cal bp.

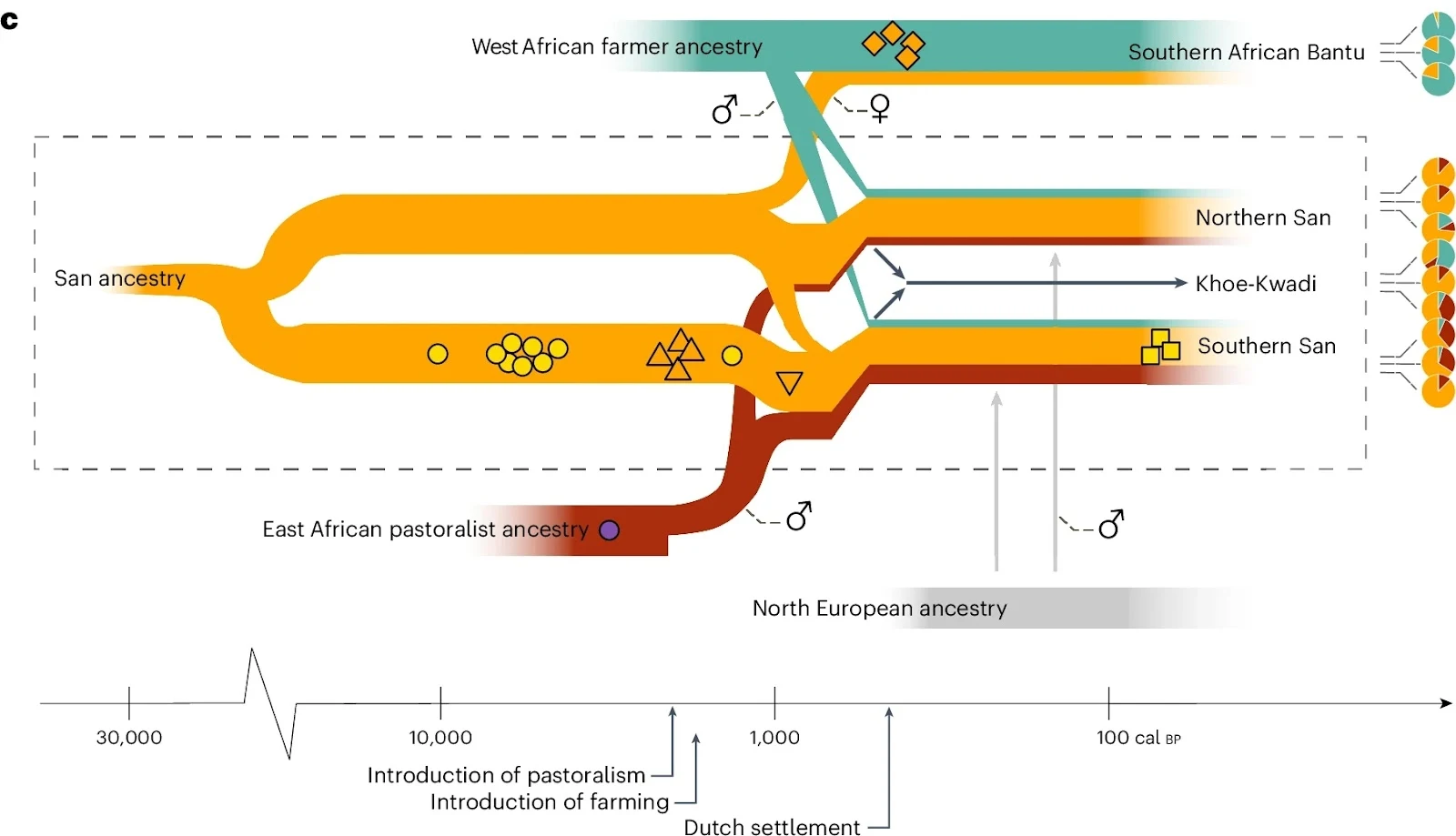

Yet, the events of the last 1,300 years had a substantial impact on the local gene pool of South Africa. Today, all San and Khoe populations are admixed with one or both of East African Pastoralist and West African Farmer ancestry1,2,7,8. The collapse of the LSA population structure was accelerated by the arrival of European settlers in the mid-seventeenth century62. Together with the continuous loss of oral traditions, these issues contribute to our poor understanding of the prehistoric southern African population structure. Using allele-frequency and IBD segment-based analyses, we were able to show that the present-day San and Khoe inhabitants of South Africa are, despite recent periods of disruption under Dutch and British rule, still directly related to the ancient Oakhurst individuals of the last 10,000 years. Especially among the ‡Khomani, Karretjiemense and Nama, who belong to the most admixed San/Khoe groups in southern Africa, some individuals still trace most of their ancestry back to these LSA hunter-gatherers. This also applies to the three historic San individuals from Sutherland dating to the late nineteenth century, who show only minor ancestry contribution from outside southern Africa and otherwise close autosomal and mitochondrial similarity to the LSA Oakhurst population41, demonstrating that the early Holocene gene pool of the Western Cape persisted in some regions throughout the last 2,000 years without major changes and that in some parts of southern Africa the long-lasting population continuity was not completely disrupted. c, Summary of the inferred population history of the San and Khoe in southern Africa. Sex symbols indicate male- and female-biased reproduction. Note that pastoralism and farming both appeared in present-day South Africa at about the same time, 2,000 years ago. Symbols and colours correspond to Fig. 1.

c, Summary of the inferred population history of the San and Khoe in southern Africa. Sex symbols indicate male- and female-biased reproduction. Note that pastoralism and farming both appeared in present-day South Africa at about the same time, 2,000 years ago. Symbols and colours correspond to Fig. 1.

Gretzinger, J., Gibbon, V.E., Penske, S.E. et al. 9,000 years of genetic continuity in southernmost Africa demonstrated at Oakhurst rockshelter. Nat Ecol Evol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02532-3

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

But, as the study of palaeoanthropology is revealing, this is typical of how the human population radiated out of East Africa during its evolution from Australopithecine ancestors, to exist for extended periods as isolated geographical populations, which them merged again with other populations. This process continued as the evolving hominin line speciated and interbred in various parts of its range, behaving like a ring species, both before and after the anatomically modern version of Hominidae, Homo sapiens, emerged as a distinct species.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

No comments:

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.