This article is best read on a laptop, desktop or tablet

The Iliamna Lake harbor seals are one of only a handful of seals that live wholly in fresh water, the best-known example of which is the Lake Baikal seal in Russian Central Asian.

The Alaskan seals have probably been isolated for thousands of years having entered the lake when it was connected to the Pacific before it became isolated from the ocean. The seals have lived there in isolation ever since. These are the classic conditions for allopatric speciation to occur as the founder effect, genetic drift and local environmental selectors cause them to diverge genetically from their parent population in the Pacific.

Lake Iliamna, Alaska and its harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). Lake Iliamna, located in southwestern Alaska, is the largest freshwater lake in the state and the third largest entirely within the U.S. by surface area, covering about 1,012 square miles (2,622 square kilometers). The lake stretches about 80 miles long and up to 25 miles wide, with depths reaching 1,000 feet in some areas. Surrounded by rugged mountains, forests, and tundra, the region is remote and largely uninhabited, but it supports diverse wildlife and is home to important subsistence fishing for local Alaska Native communities.Now a team of marine biologists led by Florida Atlantic University have succeeded in carrying out a genomic analysis and concluded that this population of seals is indeed an example of allopatric speciation in progress, just as the Theory of Evolution predicts.

Geographical Features

- Location: Southwest Alaska, north of the Alaska Peninsula.

- Water Sources: The lake is primarily fed by several rivers, including the Newhalen River, which is its main inflow. It drains westward into Bristol Bay via the Kvichak River.

- Climate: The area experiences a cold, subarctic climate, with long, harsh winters and short, cool summers.

Ecology of Lake Iliamna

The lake is an ecological gem, supporting a wide variety of plant and animal species. The nutrient-rich waters provide ideal conditions for aquatic life, and the surrounding wilderness shelters a diversity of terrestrial fauna. Lake Iliamna is most notable for its salmon runs, particularly sockeye salmon, which spawn in the lake’s tributaries and attract both wildlife and human fishers.

Harbor Seals in Lake Iliamna

One of the lake’s most unique ecological features is its population of harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). These freshwater harbor seals are a rare phenomenon, as harbor seals typically inhabit marine environments. Lake Iliamna is one of the few known places in the world where harbor seals live in freshwater year-round.

Key Points about the Iliamna Harbor Seals:

- Freshwater Habitat: Unlike most harbor seals, which reside in saltwater coastal areas, the Iliamna seals are fully adapted to life in freshwater. Their presence has intrigued biologists and raised questions about their origin, adaptation, and behavior.

- Origin: It's believed that these seals might have entered the lake during a time of higher sea levels, possibly during the Pleistocene era when glaciers retreated, connecting Iliamna with the sea.

- Diet: The seals primarily feed on the abundant fish species in the lake, especially salmon. Their diet likely mirrors that of marine seals, with a focus on local fish species that migrate or spawn in the lake.

- Population Size: The exact population of Iliamna harbor seals is not well-documented but is considered small, numbering in the hundreds. The seals are elusive and can be difficult to study due to the remote location and size of the lake.

- Behavior and Adaptations: These seals exhibit behaviors similar to their marine counterparts, including hauling out on rocks and ice during the warmer months. Little is known about their specific adaptations to a freshwater lifestyle, though they seem to thrive in the environment.

- Conservation Status: Harbor seals in Lake Iliamna are not currently listed as endangered, but concerns exist about the potential impacts of climate change and human activity, such as proposed mining projects, on the lake’s ecosystem.

Cultural and Economic Importance

Lake Iliamna, including its harbor seals, plays an essential role in the lives of local indigenous communities, particularly the Dena'ina Athabascans and the Yup’ik people. The lake's fishery, particularly for salmon, is vital for subsistence, and the seals themselves are also of cultural significance.

There have been some conservation efforts to protect the seals and the lake's pristine ecosystem, especially with the ongoing debate over the proposed Pebble Mine, a large-scale mining project that could threaten the environment and local wildlife. The seals have become a symbol for those opposed to the mine, as their unique freshwater habitat could be jeopardized by industrial activity.

In addition to scientific curiosity, the seals are often linked to local legends and folklore. Some local stories even mention mysterious creatures in the lake, contributing to a rich cultural narrative surrounding the area.

Research and Studies

Ongoing research seeks to better understand these seals' genetic differentiation from their marine relatives, how they’ve adapted to freshwater conditions, and what environmental pressures might influence their survival. Scientists continue to study the lake's unique ecosystem, trying to better understand the role these seals play in the broader environment.

In conclusion, Lake Iliamna’s harbor seals are a fascinating example of how wildlife can adapt to new and unusual environments. Their presence adds to the ecological and cultural richness of this remote Alaskan lake.

Are there any know examples of them interbreeding with marine harbor seals or is this an example of allopatric speciation?

There is no well-documented evidence of interbreeding between the freshwater harbor seals of Lake Iliamna and marine harbor seals, largely due to their geographical isolation. This separation between the two populations supports the idea of allopatric speciation, a process where a population is geographically isolated from other populations of the same species, potentially leading to the development of distinct species over time.

Allopatric Speciation in Lake Iliamna Harbor Seals

Allopatric speciation typically occurs when a physical barrier—like a mountain range, glacier, or in this case, a separation between marine and freshwater environments—prevents gene flow between populations. Over time, isolated populations can evolve differently due to genetic drift, local adaptation, or divergent selective pressures in their respective environments.

In the case of the Iliamna harbor seals:

- Geographical Isolation: These seals are isolated in Lake Iliamna, which is not directly connected to the ocean. While they are part of the same species (*Phoca vitulina*) as marine harbor seals, this separation likely occurred thousands of years ago, possibly during the retreat of glaciers at the end of the last ice age.

- Divergent Adaptations: The seals in Lake Iliamna have adapted to a freshwater environment, with different prey availability, water chemistry, and possibly changes in behavior or physiology to thrive in this unique habitat. Although no major morphological differences have been noted yet, their ecological separation could, over time, lead to further divergence.

- No Evidence of Interbreeding: Given the remoteness of the lake and the fact that it is not connected to the ocean, there’s no known mechanism for these freshwater seals to regularly encounter marine populations. This isolation reinforces the possibility of speciation. The absence of gene flow between these populations suggests that interbreeding is unlikely.

However, it is still unclear how long the Iliamna seals have been isolated, and genetic studies have not yet conclusively shown significant genetic divergence from marine harbor seals. This means that while the Iliamna seals show characteristics of an allopatric population, they may not have yet reached full speciation. Continued research on their genetics will be key to understanding whether they are on a path toward becoming a distinct species.

In short, the Iliamna seals seem to represent an example of early allopatric speciation, though further isolation and time would be required for them to become a fully distinct species from their marine counterparts.

They have just published their findings, open access in the The Royal Society Biology Letters and have explained it in a Florida Atlantic University news item:

Iliamna Lake Harbor Seals Genetically Isolated from Pacific Ocean

There are only five seal populations worldwide that live year-round in freshwater habitats. The Baikal seal, probably the most well-known, lives in the deepest, oldest lake in the world, 1,600 kilometers from the ocean in Lake Baikal, central Siberia. However, perhaps the most enigmatic population of freshwater seals can be found a little closer to home in Alaska’s Iliamna Lake.

Despite their wider anonymity, the Iliamna seals have long been known to the Dena’ina Athabascan and Central Yupik peoples of southwestern Alaska, who have deep cultural and dietary ties to this small pinniped. Unlike other freshwater seal populations globally, the seals in Alaska’s largest lake have been largely overlooked by scientists. Their remote location and the difficulties in studying these elusive animals have contributed to this lack of attention. It wasn’t until 2013 that genetic research finally identified them as harbor seals.

A long-standing question has been whether the seals in Iliamna Lake were separate from those in Bristol Bay, the nearest marine population. The bay is connected to the lake by the 110 kilometer-long Kvichak River. Harbor seals commonly move more than 200 kilometers, and the relatively short distance between the lake and Bristol Bay, combined with sporadic sightings of seals in the river has led to the hypothesis that they move regularly between the freshwater and marine habitats.

A team of scientists, led by Florida Atlantic University, in partnership with local indigenous communities set out to find the answer. Researchers conducted a genetic study of seals in the lake and compared them to seals not only in Bristol Bay, but across almost the entire Pacific Ocean range of the species, from Japan to California.

Results of the study, published in the journal Biology Letters, reveal that the seals in Iliamna Lake are notably different at multiple genetic markers from the seals downstream. Findings indicate that they are likely evolutionarily, reproductively and demographically discrete from other seal populations in the Pacific and could be a unique endemic form of harbor seal.

The seals in Iliamna Lake were significantly differentiated from seals sampled at several regions across the Pacific, including in Japan, the Commander Islands in Russia, other locations in Alaska, and in California. They had lower levels of variation at the selectively neutral markers investigated, and somewhat higher estimates of inbreeding compared to the marine populations.

Our findings are both striking and unexpected. Indigenous knowledge and early Russian explorers’ accounts suggest that the seals have been in Iliamna Lake for at least 200 years. However, it’s still uncertain whether they have been there for a longer period or if the observed differences might indicate that the Iliamna seals represent a separate subspecies, similar to other freshwater seal populations.

Dr Greg O’Corry Crowe, Ph.D., senior author

Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute

Florida Atlantic University, Fort Pierce, FL USA.

The initial critical samples for this research came from subsistence hunters, providing early hints that seal movements between Iliamna Lake and Bristol Bay might be limited. However, the small sample sizes necessitated cautious interpretation of these preliminary results. With limited prospects for more samples, the research faced a standstill.

Progress resumed when a University of Washington team, including then-graduate student and co-author Donna Hauser, Ph.D., now a research associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, International Arctic Research Center, collected seal scat (feces samples) from various locations around Iliamna Lake in collaboration with co-author Thomas P. Quinn, Ph.D., a professor in the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington. This new batch of samples allowed for expanded genetic analysis and reinvigorated the study.

Collaborating with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists, the FAU team processed hundreds of scat samples. Though extracting adequate DNA proved challenging, and many samples were unusable, the scat analysis yielded a four-fold increase in sample size and the statistical power needed for a more in-depth analysis.

Excluding samples that don’t meet genetic screening standards can be disheartening, especially after investing so much time and effort. Despite the frustration and long hours in the lab, the eventual success and valuable data make it all worthwhile. Hard work pays off when we achieve meaningful results.

Tatiana Ferrer, first author, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute

Florida Atlantic University, Fort Pierce, FL USA.

The FAU team and NOAA are planning more research on Iliamna seals, which will include more sampling and the addition of genomic analyses, to further resolve their relationships with other seal populations, and more broadly reveal how genetic diversity is generated, lost or maintained in small, isolated populations, and how typically marine species adapt to freshwater habitats.

We can now confidently say there is a separate population of seals in the lake that receives no, or very few immigrants from the much larger marine harbor seal populations nearby. I’m really excited for further studies to determine whether the lake seals differ from their marine counterparts in significant aspects of their ecology and evolution.

Peter Boveng, co-author

NOAA Fisheries

Alaska Fisheries Science Center

Seattle, WA, USA.

Concern for Iliamna Lake, its flora and fauna, has increased recently with the growing interest in mineral exploration and development in the region.

My fascination with Iliamna seals began during my undergraduate studies at the University of Washington, leading to my first research project on their diet and behavior. That work, published in 2008, was the only study on them for years, Revisiting Iliamna Lake in 2015 and 2017 with my family, I saw an opportunity to collect valuable samples on this unique seal population. I hope this research sparks further studies and encourages partnerships with local communities and Indigenous Knowledge holders.

Associate Professor Dr Donna D.W. Hauser, co-author

International Arctic Research Center

University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA.

Detailed scientific data is needed to inform species management and conservation. The authors hope findings from this study could inform co-management of seals and assist NOAA, the federal agency responsible for harbor seal management in Alaska, and with decision-making.

I have been curious about these seals since I first started working on Iliamna Lake in 1987, but never made any progress until Donna Hauser’s study of their diets over two decades ago. To see these remarkable genetic results, and the growing research connection to the local community, is simply marvelous. I am confident that there are more discoveries to come on the physiology and behavior of the seals as well as their evolution.

Thomas P. Quinn, co-author

School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences

University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Other study co-authors are David Withrow, a former research scientist at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center; and Vladimir Burkanov, Ph.D., chief scientist at North Pacific Wildlife Consulting.

This study has been a great leap forward in our understanding of these seals; however, more research is needed as it raised a whole new set of questions. That’s just the nature of science. We hope to work with the Iliamna and Bristol Bay communities to continue to address their questions, learn about these remarkable animals, and assist in ensuring the Iliamna Lake seal’s future.

Dr Greg O’Corry Crowe, Ph.D.

AbstractHere we have as clear an example as you could wish for of how, just as Dawin and Wallace proposed, an isolated population tends to diverge from its parent population end will eventually become a new species. The question with this genetically isolated population of harbor seals is whther this divergence has progressed to the stage at which they can be considered a separate species. Of course, because there is no contact between the two populations the interbreeding test can't be applied and there will have been few if any drivers for barriers to hybridiation to arise. This highlights a problem for taxonomy, which arises because taxonomic systems were devised for classifying distinct species whereas the process of speciation is usually a slow one over time, of judging how far along the contiuum from the same species, through subspecies to distinct species based on genomic data alone.

Freshwater populations of typically marine species present unique opportunities to investigate biodiversity, evolutionary divergence, and the adaptive potential and niche width of species. A few pinniped species have populations that reside solely in freshwater. The harbour seals inhabiting Iliamna Lake, Alaska constitute one such population. Their remoteness, however, has long hindered scientific inquiry. We used DNA from seal scat and tissue samples provided by Indigenous hunters to screen for mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite variation within Iliamna Lake and eight regions across the Pacific Ocean. The Iliamna seals (i) were substantially and significantly discrete from all other populations (\(\bar{x}F_{\mathrm{st-mtDNA}}= 0.544, \bar{x}\theta_{\mathrm{st-mtDNA}} = 0.541, \bar{x}F_{\mathrm{st-microsatelites}}= 0.308\)), (ii) formed a discrete genetic cluster separate from all marine populations (modal ∆k = 2, PC1 = 14.8%), had (iii) less genetic diversity (Hd, π, Hexp), and (iv) higher inbreeding (\(F\)) than marine populations. These findings are both striking and unexpected revealing that Iliamna seals have likely been on a separate evolutionary trajectory for some time and may represent a unique evolutionary legacy for the species. Attention must now be given to the selective processes driving evolutionary divergence from harbour seals in marine habitats and to ensuring the future of the Iliamna seal.

1. Introduction

Few seal populations persist year-round in freshwater habitats. The small population of seals in Alaska’s Iliamna Lake (figure 1) is one of just five populations worldwide where seals are known to consistently inhabit freshwater lakes [1,2]. The other four are recognized as either distinct species (the Baikal seal, Pusa siberica), or subspecies (the Ladoga seal, Pusa hispida ladogensis, the Saimaa seal, Pusa h. saimensis and the Ungava seal, Phoca vitulina mellonae) [3,4]. The population from Iliamna Lake numbers approximately 400 individuals [5,6], has received comparatively little scientific attention to date [1,2,5,7,8], and provides an important cultural and dietary resource to local Indigenous communities [1,2]. Only relatively recently, a genetic study confirmed Iliamna Lake seals (termed ILS for the rest of this paper) were harbour seals, Phoca vitulina, and not the closely related spotted seal, P. largha [9].

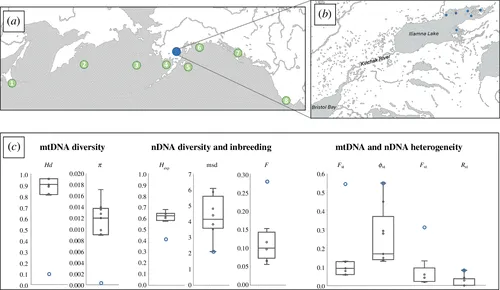

Iliamna Lake is the largest in Alaska, with a surface area of 2622 km2, an average depth of 44 m and a maximum depth of 301 m [10], and it drains westward into Bristol Bay via the 110 km-long Kvichak River (figure 1b ) providing the possibility for seals to move between the two water bodies and potentially interbreed. The lake supports a large population of sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka, that appears to provide a substantial, if seasonally limited, food resource [7]. Following a 2012 petition to list ILS as ‘Threatened’ or ‘Endangered’ under the US Endangered Species Act (ESA), the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) conducted a status review. In 2016, NMFS concluded ILS were a ‘discrete’ population under the ESA but were unable to determine if they were also of ‘significance’ to the broader taxon, the eastern Pacific subspecies P. v. richardii [11,12]. NMFS’s determination of discreteness relied largely on a preliminary report indicating that ILS had low mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variation (all individuals possessed the same haplotype) and were likely genetically differentiated (for both nDNA and mtDNA) from seals in Bristol Bay, the closest marine habitat [9]. However, that study was constrained by small sample size (n = 13). Several questions remain that could significantly influence conservation and management actions on ILS, including the discreteness of this population and its significance to the species. In the current study, we substantially increased sample size from ILS through successful screening of seal scat samples for both mtDNA and nDNA (microsatellite) variations. We also assessed patterns of genetic diversity and levels of inbreeding within, and genetic differentiation between, ILS and eight regions of harbour seals across their Pacific range from Japan to California, encompassing the two recognized Pacific subspecies: the western P. v. stejnegeri and eastern P. v. richardii. Figure 1. (a) Locations for eight harbour seal regions across the North Pacific range (green) and Iliamna Lake (blue). (b) Location of Iliamna Lake connected to Bristol Bay via the Kvichak River with sampling locations denoted by blue symbols. (c) Box-and-whisker plots (central tendency and variance) of genetic diversity, differentiation and inbreeding (see text for details). Iliamna seals are denoted by blue circles.

Figure 1. (a) Locations for eight harbour seal regions across the North Pacific range (green) and Iliamna Lake (blue). (b) Location of Iliamna Lake connected to Bristol Bay via the Kvichak River with sampling locations denoted by blue symbols. (c) Box-and-whisker plots (central tendency and variance) of genetic diversity, differentiation and inbreeding (see text for details). Iliamna seals are denoted by blue circles.

On thing we can be sure of however is that the harbor seals of Iliamna Lake are in the process of allopatric speciation, just as the Theory of Evolution predicts.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.