Wild western chimpanzee using a stick tool to extract high-nutrient food.

Credit: Liran Samuni, Taï Chimpanzee Project (CC BY 4.0)

Chimpanzees are famous for making and using tools, especially sticks, for obtaining nutritional foods like grubs and termites, but using them takes time, just like a human child needs to develop motor skills to use tools such as pens and pencils with sufficient dexterity.

How they do so, and the stages they go through, was described recently in an open access paper in PLOS Biology by a team of animal behaviourists from l'Institut des Sciences Cognitives Marc Jeannerod (The Marc Jeannerod Institute of Cognitive Sciences), Lyon, France; the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany, and the German Primate Center, Göttingen, Germany, who analyzed film of wild chimpanzees making and using stick tools in the Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire.

They concluded that, like human children, acquiring motor skills is not just a matter of practice, important though that it, but also depends on a protracted childhood during which they observe and copy adults with the necessary skills. In other words, young chimpanzees learn skill from their parents and elders, like a human apprentice.

The team's work was explained in information made available ahead of publication by PLOS, and published in SciTechDaily.com:

Humans have the capacity to continue learning throughout our entire lifespan. It has been hypothesized that this ability is responsible for the extraordinary flexibility with which humans use tools, a key factor in the evolution of human cognition and culture.

Human and Chimpanzee Learning Compared

In this study, Malherbe and colleagues investigated whether chimpanzees share this feature by examining how chimps develop tool techniques as they age. The authors observed 70 wild chimps of various ages using sticks to retrieve food via video recordings collected over several years at Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire.

As they aged, the chimps became more skilled at employing suitable finger grips to handle the sticks.

Continuous Skill Development

These motor skills became fully functional by the age of six, but the chimps continued to hone their techniques well into adulthood. Certain advanced skills, such as using sticks to extract insects from hard-to-reach places or adjusting grip to suit different tasks, weren’t fully developed until age 15.

This suggests that these skills aren’t just a matter of physical development, but also of learning capacities for new technological skills continuing into adulthood.

Insights into Evolutionary Learning

Retention of learning capacity into adulthood thus seems to be a beneficial attribute for tool-using species, a key insight into the evolution of chimpanzees as well as humans. The authors note that further study will be needed to understand the details of the chimps’ learning process, such as the role of reasoning and memory or the relative importance of experience compared to instruction from peers.

The authors add, “In wild chimpanzees, the intricacies of tool use learning continue into adulthood. This pattern supports ideas that large brains across hominids allow continued learning through the first two decades of life.”

AbstractAlthough an opposable thumb gave humans an edge when it came to developing the necessary motor skills to use tools, especially where fine control is needed, the most important aspect is the one we share with chimpanzees - a large brain with the capacity to continue learning into adulthood, and a relatively long childhood. The chimpanzees' lack of an opposable thumb is not a barrier to acquiring these skills because they have the cognitive ability to select different grips depending on the precision needed. Since this prolonged learning to gain the maximum benefit from tool-using is present in two closely related species, the probability is that it was present in our common ancestor.

Tool use is considered a driving force behind the evolution of brain expansion and prolonged juvenile dependency in the hominin lineage. However, it remains rare across animals, possibly due to inherent constraints related to manual dexterity and cognitive abilities. In our study, we investigated the ontogeny of tool use in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), a species known for its extensive and flexible tool use behavior. We observed 70 wild chimpanzees across all ages and analyzed 1,460 stick use events filmed in the Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire during the chimpanzee attempts to retrieve high-nutrient, but difficult-to-access, foods. We found that chimpanzees increasingly utilized hand grips employing more than 1 independent digit as they matured. Such hand grips emerged at the age of 2, became predominant and fully functional at the age of 6, and ubiquitous at the age of 15, enhancing task accuracy. Adults adjusted their hand grip based on the specific task at hand, favoring power grips for pounding actions and intermediate grips that combine power and precision, for others. Highly protracted development of suitable actions to acquire hidden (i.e., larvae) compared to non-hidden (i.e., nut kernel) food was evident, with adult skill levels achieved only after 15 years, suggesting a pronounced cognitive learning component to task success. The prolonged time required for cognitive assimilation compared to neuromotor control points to selection pressure favoring the retention of learning capacities into adulthood.

Introduction

Tool use behavior, defined as the use of an environmental object to alter more efficiently the form, position, or condition of another object or organism [1,2], has been documented across various animal taxa ([2,3]; Apes: [4,5], Birds: [6,7], Insects: [8,9], Monkeys: [10]). Tool use can facilitate access to highly nutritious food items that are otherwise inaccessible, as well as fulfill other functions such as communicating or gathering sensory information [11]. It has been suggested that tool use behavior is differentiated into stereotyped and flexible use [12]. Whereas stereotyped tool use necessitates individual learning but not reasoning, flexible tool use requires social input, individual reasoning, and understanding of action causality [12,13]. Flexible tool use is particularly relevant during tasks in which multiple steps are required to be successful or when the perceptual distance between the problem and solution is large (e.g., extractive tool use wherein the target is not directly visible) [14,15]. The way in which humans use tools flexibly is unmatched [16]. One hypothesis that explains this ability in humans is the capacity to continue to learn across the entire lifespan, which is considered connected to the human phenomenon of having both prolonged brain maturation and prolonged juvenile dependency [17]. While other species also show prolonged development and parental association (e.g., apes, whales, elephants, New Caledonian crows), it remains unclear if this relates to prolonged learning of complex foraging, here examined in tool use behavior.

For many species, the capacity to manipulate a tool with precision, coordination, and control is physically constrained by morphological features. For example, New Caledonian Crows compared to other avian species have a bill morphology adapted for enhanced tool manipulation [18,19], and primates have opposable thumbs which offer improved motor dexterity. Thumbs have been hypothesized to be essential in facilitating progression in tool use and tool making during human evolution [20–24]. The ability of humans to independently oppose their thumb to their other digits offers the possibility to manipulate objects and tools with either power and/or precision [23]. However, not all primates’ thumbs are equivalent, with intrinsic hand proportions (e.g., how long the thumb is relative to the other digits, how many muscles are involved, what is the mobility at the thumb to wrist joint) likely limiting the manipulative abilities of different species. Examining the use of the thumb and other digits during tool use behavior of extant nonhuman primates can offer a comparative perspective on the evolution of morphology related to tool use and assess the extent to which morphology constrains tool use skills.

Alongside morphology, cognition is also considered as a potential constraint on tool use behavior and development (see [25]). For example, flexible tool use behavior is thought to require the ability to combine different experiences to solve novel problems, otherwise known as reasoning [13,26], conceptual knowledge about objects [27], working memory [14], hierarchical cognition [28], and socio-cognitive capacities such as emulation and imitation in the case of socially learned tool use [29]. Comparative studies of nonhuman animals show considerable variation in relevant cognitive capacities (e.g., [30–32]), highlighting the potential for cognition to explain why flexible tool use is observed in some species but not others.

While a number of different species have been shown to use tools flexibly (e.g., gorillas [33], sea otters [34], orangutans [35], New Caledonian crows [6], bottlenose dolphins [36], Goffin’s cockatoo [37], woodpecker finch [38], and bearded capuchins [39]), chimpanzees are one of few species where flexible tool use behavior is regularly observed across individuals, populations, tool materials, and contexts [40]. As one of our closest living relatives, chimpanzees share some similarities with humans that may inform tool use acquisition and use. The ability to socially learn from others allows for material traditions and culture to exist between communities and populations [40,41]. While significant differences exist between the hand anatomy of chimpanzees and humans, with the former having long digits and small and weak thumb considered inoperant in precise handling [22], chimpanzees employ all hand grips described in humans [23,42–46], including the pad-to-pad precision grip, a complex hand grip long thought to be unique to humans ([47,48]; although see: [22,24,46]).

Chimpanzees also share with humans a prolonged developmental period and maternal dependency [49–53]. Within the hominin lineage, it has been hypothesized that prolonged juvenile dependency, which is related to parental provisioning, facilitated prolonged brain development (e.g., [54]), which in turn enabled protracted learning capacities needed for complex foraging and tool use [17]. Chimpanzees may not continue extensive parental provisioning after weaning at age 5 years old, however, individuals that experience maternal loss after weaning and before adulthood compared to those that do not, lose out on fitness [50,52,53]. This suggests that mothers continue to offer benefits to offspring, although what these benefits are, is not well understood. One possibility is that acquiring the skills for the highly flexible tool use demonstrated by chimpanzees requires protracted learning across development. Specifically, we predict that tool use skills to extract difficult-to-access, high-nutrient foods, may require protracted learning. To assess this, we tease apart development of the motor control needed to manipulate tools (hand grip type) and skill acquisition required to fit specific tool actions to food tasks.

Previous studies have proven instrumental for our understanding of the processes involved in chimpanzee tool use acquisition [55–57]. However, due to their slow life histories, studies examining how chimpanzee tool use manipulative skills develop across their lifetime, especially in the wild, are rare. This gap in the literature impedes our understanding of the motor and cognitive skills that may underlie chimpanzee natural tool use behavior. Here, we capitalized on a video dataset of 70 wild chimpanzees using sticks as tools for extractive foraging, collected over 7.5 years. Using cross-sectional data, we examined how the hand grip and action used to manipulate stick tools varied across ontogeny and tool use tasks. We hypothesized that ontogeny will lead to the maturation of both the grip to hold and use a stick tool, and the task understanding in the context of stick tool use. To assess hand grip use, we examined (i) how hand grip preferences change with age; and (ii) whether grips involving the use of one or several digits independently increased accuracy and efficiency. To assess skill specialization and task understanding, we examined (i) whether hand grips changed according to the action required to complete the task (i.e., whether requiring power or precision); and (ii) whether action selection per task became more specific with age. If learning is involved in these choices, we expected older individuals to be better at using the suitable hand grip and actions for a given task compared to younger individuals.

Given the protracted developmental dependency observed in chimpanzees, we expect that chimpanzee tool manipulation skills will develop slowly through ontogeny, extending beyond weaning age. Specifically, as motor control matures, we expect stick tool hand grip to become optimized to the task in hand. When task experience is required, we expect learning the action required to extract difficult to access foods using stick tools will continue to develop for some years after hand grip motor control has become proficient.

[…]

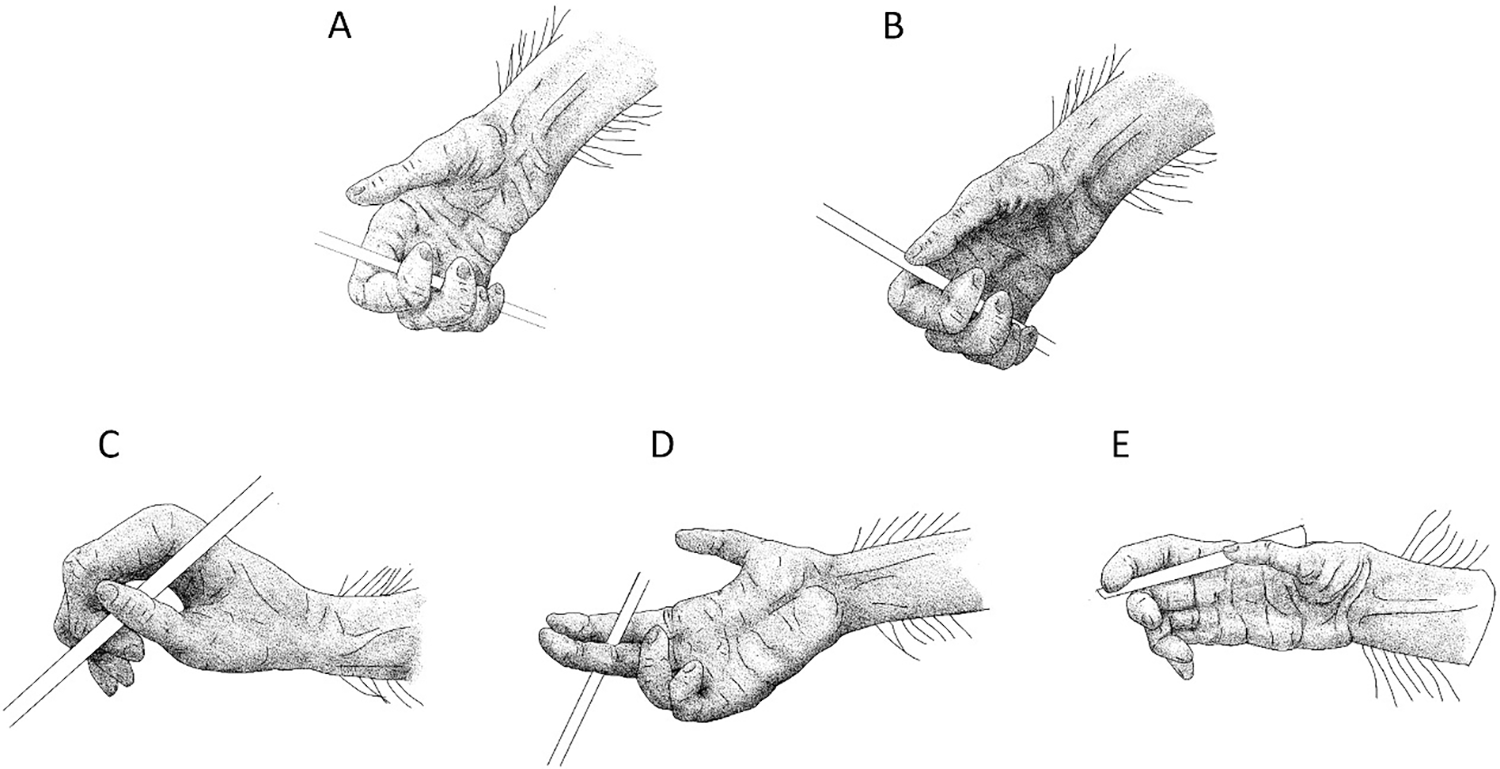

Conclusions Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Representation of the different hand grip used by chimpanzees of the Taï National Park in order to hold and manipulate a stick tool to access food: (A) full hand grip, (B) full hand thumb grip, (C) digits grip category 1, (D) digits grip category 2, (E) digits grip category 3.Drawn by Oscar Nodé-Langlois, TCP.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002609.g001

Our results are in line with Hunt and colleagues’ [12] hypothesis, showing that the development of complex manipulation in chimpanzees is not only dependent on morphological features or neuromotor maturation but also has a considerable cognitive component essential for flexible tool use expression. Learning and understanding the action needed to efficiently extract food plays a significant role in developing adequate adult-like skills which may well be facilitated by the protracted dependency period experienced by wild chimpanzees. Motor and cognitive maturation likely work in concert, in informing the development of hand grip to use stick tools during ontogeny. Wild chimpanzees seem to be able to find alternative strategies to limit their hand anatomy restrictions by choosing hand grips that allow them to apply both power and precision when using stick tools. Ontogenetic analyses demonstrate that morphological features are likely not the principal limiting factor in allowing the expression of flexible tool use behavior, as more cognitively challenging tasks were slower to develop. Task experience and decision-making seem essential for stick tool use behavior to occur across a range of contexts. Chimpanzees have one of the most extensive tool kit of nonhuman animals [2]. Whether the limiting factor preventing more tool use and manufacture in chimpanzees populations is cognitive capacity in specific domains (e.g., action planning) or is rather due to limited exposure to role models to acquire culture cumulatively (see [109,110]) remains to be examined.

And once again, what creationists once claimed to be evidence of the unique, special creation of humans, turns out to be evidence instead of our evolution from a common ancestor with chimpanzees.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

How did you come to be here, now? This books takes you from the Big Bang to the evolution of modern humans and the history of human cultures, showing that science is an adventure of discovery and a source of limitless wonder, giving us richer and more rewarding appreciation of the phenomenal privilege of merely being alive and able to begin to understand it all.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.