Shanidar Z: what did Neanderthals do with their dead?

65,000 years before creationists believe the Universe existed, and before anatomically-modern humans had migrated out of Africa, a community of Neanderthals were living in a the Shanidar cave in what is now northern Iraq.

These Neanderthals also appear to have used the same cave in which to bury their dead, the skeletons of which are now being excavated to learn more about how these hominins lived.

And the picture emerges of a sophisticated people, very different from the brutal sub-human animals Victorian archaeologists depicted them as when Neanderthal remains were first discovered. Like many Creationists and US white supremacists today, Victorians were so wedded to the idea that modern (European) humans are the pinnacle of creation, that they could not conceive of the idea that there may once have been earlier humans who had anything approaching their level of sophistication.

One of the skeletons is of a man with a disabled arm who was probably deaf and had a head trauma that would have made him disabled and dependent, yet he had lived a long time, showing evidence of care and compassion.

Readers of Jean M. Auel's excellent series of imaginative, but painstakingly researched books about a Homo sapiens girl, Ayala, raised by Neanderthals will probably recognise Mog-ur, the Neanderthal tribal elder and shaman who befriended Ayala from that description...

The burials also suggest a sense of an after-life and care for the dead in that after-life. One skeleton is placed with its head pillowed on its hand presumably to make it comfortable.

One of the assembly of (female) skull fragments has been carefully removed from the rock matrix in which it was embedded and used to reconstruct her skull and then build a 3D reconstruction of how she would have appeared in life, for a BBC Netflix documentary on the excavation of the 35 individuals in the cave.

The work is the subject of an open access paper in the journal Antiquity and of a Cambridge University news article by Fred Lewsey:

In the foothills of northern Iraq is a cave that has sheltered shepherds from winter winds for generations.

It concealed Kurdish families during the reign of Saddam Hussein.

As well as aiding the living, Shanidar Cave harbours the dead.Shanidar Cave in the northern mountains of modern-day Iraq. Shelter for the living and burial place for the dead.A graveyard of 35 people laid to rest over 10,000 years ago was uncovered in Shanidar Cave by archaeologist Ralph Solecki in 1960.

This cemetery was found at the end of four seasons of excavation, during which time Solecki discovered something more extraordinary: the partial remains of ten Neanderthal men, women and children. Mid-20th century techniques could only date them to over 45,000 years ago.

Stockier than us, with heavy brows and sloping foreheads, it had long been assumed that Neanderthals were primitive and animalistic: subhuman. Evolutionary losers ultimately rendered extinct by their own deficiencies.

However, Shanidar Cave suggested a far more sophisticated creature. One male had a disabled arm, deafness and head trauma that likely rendered him partially blind. Yet he had lived a long time, so must have been cared for. Signs of compassion.

Four individuals were found clustered together in a “unique assemblage”, with ancient pollen clumped in the sediment around one of the bodies. Solecki claimed this as evidence of Neanderthal burial rites: repeated interments; the laying of flowers on the deceased. Human-like ritual behaviour.

Controversy ensued, and still lingers. Does Shanidar Cave show that Neanderthals mourned for and buried their dead? Were they far closer to us in thought and action? What does this mean for the evolution of our lineage?

One such student essayist at Cambridge would eventually be among the first archaeologists allowed back into Shanidar Cave for more than fifty years.Undergraduates across the world studying pre-history get asked a version of: Neanderthals were nasty, brutish and short – discuss. The Shanidar flower burial always comes up.

Professor Graeme Barker, Co-author

McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research

University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

Ralph Solecki didn’t finish excavating at Shanidar. He tried to re-excavate several times – reaching the foot of the hill in 1978 – but was stymied by political unrest, and his neglected trenches filled with rubble. Solecki died in March last year aged 101.I stood at the bottom of the hill leading up to the cave and thought: how am I getting to do this?

It was mind-blowing. School hadn’t taught us about human evolution, and I was fascinated by what Neanderthal behaviour might tell us about our own species.

Dr Emma Pomeroy, lead author

Department of Archaeology

University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

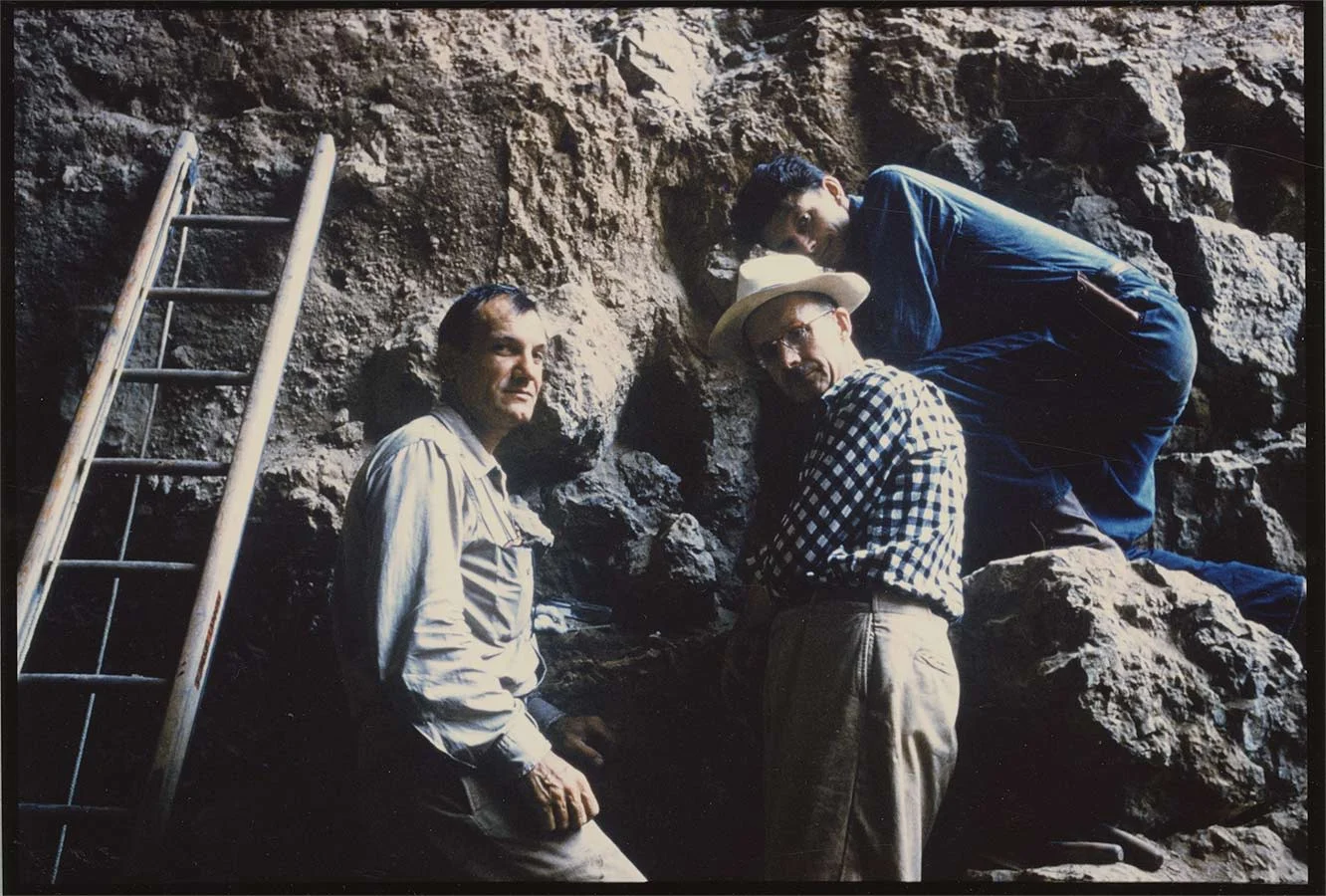

In 2011, Barker was invited by the Kurdistan Regional Government to re-excavate Shanidar. Shanidar 4 (the 'flower burial') in situ in 1960, with Ralph Solecki on the left.Credit: Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki papers,

Shanidar 4 (the 'flower burial') in situ in 1960, with Ralph Solecki on the left.Credit: Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki papers,

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Initial digging in 2014 stopped after two days when ISIS got too close, but resumed in earnest the following year. Pomeroy joined the team in 2016 as the project’s paleoanthropologist.Most archaeologists would jump at the chance. The fact that Solecki was enthusiastic was a clincher.

Professor Graeme Barker

The Neanderthals had been found by Solecki between three and seven metres down, and the idea was to reopen the trenches to get samples of soil, in the hope of pulling new evidence for age or climate from microscopic mineral and animal fragments.

We thought with luck we’d be able to find the locations where Solecki had discovered the Neanderthals, and see if we could date sediments with techniques they didn’t have back in the fifties. We didn’t think we’d be lucky enough to find more Neanderthal bones.

Professor Graeme Barker

In 2016, down in the “Deep Sounding” of the Solecki trench, while working on the eastern face, a rib emerged from the wall, followed by the arch of a lumbar vertebra, then the bones of a clenched right hand. Archaeologists would have to wait until the following year to begin excavating the delicate remains from beneath metres of rock and soil.

During 2018 and 2019, the team uncovered a seemingly complete skull, flattened by thousands of years of sediment, and upper body bones almost to the waist – with the left hand curled under the head like a small cushion.

The first articulated Neanderthal skeleton to be found in this part of the world for a quarter of a century is over 70,000 years old. Sex is yet to be determined, but it has the teeth of a “middle- to older-aged adult”.

The find is described in a new paper published in the journal Antiquity.The bones are “heartbreakingly soft” says Pomeroy. Barker describes the consistency as akin to wet biscuit, and soil had to be slowly and meticulously scraped away, sometimes using bamboo kebab sticks. The Neanderthal skull, flattened by thousands of years of sediment and rock fall, in situ in Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan.A glue-like consolidant is then brushed on, soaking in to bolster the bone, before sections are lifted out and wrapped in foil. But the bones are just the headline act. Scoops of surrounding soil are also ferried to camp where they are washed and picked through. Barker says they collect everything larger than two millimetres.

The Neanderthal skull, flattened by thousands of years of sediment and rock fall, in situ in Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan.A glue-like consolidant is then brushed on, soaking in to bolster the bone, before sections are lifted out and wrapped in foil. But the bones are just the headline act. Scoops of surrounding soil are also ferried to camp where they are washed and picked through. Barker says they collect everything larger than two millimetres.Emma’s got an eye for where the various protuberances of bone are likely to be. It took her weeks of intense concentration working in what is pretty much a sauna in terms of heat and humidity.

Professor Graeme Barker

The painstaking work of excavating in situ is risky as the bone is so fragile. An alternative is “en bloc”: to coat the area in plaster and extract it wholesale, then excavate fully in the lab.

In the 1950s, Solecki opted for the en bloc excavation of the ‘flower burial’. Pomeroy thinks it was this extraction that left the latest Neanderthal find chopped at the waist. “In their notes they describe bones trickling out of the block. Solecki numbered the individuals; we think we have the top half of Shanidar 6, but until we can confirm this we call ours Shanidar Z.” What thrills both archaeologists is the wealth of evidence to be gleaned from Shanidar Z using technologies unavailable to Solecki.We considered en bloc, but it can be quite brutal. Crucially, it risks destroying precious evidence that may determine whether the Neanderthals were buried in a purpose-dug pit – a grave – or not.

Dr Emma Pomeroy.She is currently CT-scanning each segment of Shanidar Z in the lab at the Cambridge Biotomography Centre, and will rescan them once the layers of silt – the “matrix” – are removed. Ultimately a digital reconstruction will emerge.In the Neanderthal burial debate, archaeologists are always going back to the reports of finds from sixty or a hundred years ago, but that only gets you so far. Now we have primary evidence.

Dr Emma Pomeroy.Scans have revealed the petrous bone to be intact. Named for the Latin petrosus, or ‘stone’, it’s a wedge at the base of your skull, behind the ear, and one of the densest bones in the body. The petrous is a grail for hunters of ancient DNA, as it can preserve genetic data for millennia. We have ancient Neanderthal DNA from the North, where colder climates aided preservation. That’s how we know they bred with modern humans at some point. All non-African people still carry an average of 2% Neanderthal DNA, and a recent study from Princeton suggests most Africans also have around 0.3%. What we don’t have is Neanderthal genetics from hot and dry South West Asia, where this interbreeding most likely occurred as modern humans spilled out of Africa. Shanidar Z might be the best hope yet.A 3D rendering of the in situ positions of the Neanderthal left hand and torso as it emerged from the sediment of Shanidar Cave.Credit: Ross Lane.Some argue that competition from our species was the catalyst for Neanderthal extinction. Other theories include an inability to cope with changing climates. In the office above Pomeroy, PhD student Emily Tilby is sifting through shards of shell and bone from Shanidar snails and mice, searching for traces of temperature shift. Cross-sectional CT image showing the petrous part of the temporal and inner ear (within red box) of the new Shanidar skull.

Cross-sectional CT image showing the petrous part of the temporal and inner ear (within red box) of the new Shanidar skull.Small animals are particularly sensitive to climate change. Greenland ice cores give us a general global picture, but these tiny bones can tell us about changing climates in Kurdistan at the time when Neanderthals were roaming its mountains.

Professor Graeme BarkerShanidar Z came back from Iraq as hand luggage. When Pomeroy moved from Liverpool to Cambridge in 2018, she drove the Neanderthal down packed in a suitcase, in a car that also contained the remains of John of Wheathampsted, a 15th century abbot of St Albans (“I introduced them to eighties cheese on the radio”). Analyses of bones and sediment from the excavations are now in full swing at Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology and Liverpool John Moores University.

In the intervening decades since Solecki described the flower burial, mounting evidence of Neanderthal culture and cognition suggests a species much closer to humankind than the “brutish cavemen” of common conception.An archaeological project like this involves an ever-growing circle to help with specialist analyses. The current list includes colleagues at Belfast, Bordeaux, Copenhagen, Leiden, Liverpool, London, Orléans and Oxford Universities.

We also depend absolutely on the enthusiastic support of local Kurdish people and the Kurdistan archaeological authorities, for both of whom Shanidar Cave is core to Kurdish identity.

The questions are big, and go to the heart of what makes us human. But determining the death practices of these Neanderthals will be far from easy. It’s as if we’ve got ten or eleven bits of a million-piece jigsaw, and we haven’t even got the picture on the top of the box.

Professor Graeme Barker

Just the last few years have seen use of decorative shells and even specific cave daubings attributed to Neanderthals. However, the repeated ritual interment of the dead within a site of memory, possibly over long periods of time, would suggest cultural complexity of a higher order.See also: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-68922877 The spinal column of the Neanderthal immediately after removal, in a small block of the surrounding sediment.

The spinal column of the Neanderthal immediately after removal, in a small block of the surrounding sediment.

AbstractAnd all this was happening some 65,000 years before creationism's little god thought of creating a small flat Universe with a dome over it, centred on the Middle-East. Whatever happened to these people they left their mark on us in the shape of 1-3% of the DNA of non-African people and an estimated 0.3% of African DNA. Some schools of thought have them becoming extinct due to climate change and loss of the megafauna on which they depended, or due to inbreeding with small, isolated groups and low population density; others have anatomically modern humans replacing them either by conflict or competition for resources and still others see them not becomign extinct at all but merging into the much larger Homo sapiens population. There is now far more Neanderthal DNA in the world then there ever was at the time these people were burying their dead at Shanidar.

Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan became an iconic Palaeolithic site following Ralph Solecki's mid twentieth-century discovery of Neanderthal remains. Solecki argued that some of these individuals had died in rockfalls and—controversially—that others were interred with formal burial rites, including one with flowers. Recent excavations have revealed the articulated upper body of an adult Neanderthal located close to the ‘flower burial’ location—the first articulated Neanderthal discovered in over 25 years. Stratigraphic evidence suggests that the individual was intentionally buried. This new find offers the rare opportunity to investigate Neanderthal mortuary practices utilising modern archaeological techniques.

Introduction

Shanidar Cave is a large, south-facing, karstic cave located at around 750m asl in the foothills of the Baradost Mountains of north-east Iraqi Kurdistan (Figure 1a). Between 1951 and 1960, Ralph Solecki dug an approximately 20 × 6m trench, oriented roughly north–south, in the centre of the cave floor. At its deepest point, the trench reached 14m below the ground surface (Figure 1b). Below the Epipalaeolithic and Upper Palaeolithic (‘Baradostian’) occupation levels, Solecki discovered, at a depth of 4–7m, the skeletal remains of 10 Neanderthal men, women and children (Trinkaus 1983; Cowgill et al. 2007)—a unique assemblage that justifies the site's iconic status in Neanderthal archaeology (Solecki 1955, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1971). Solecki argued that while some of the individuals had been killed by rocks falling from the cave roof, others had been buried with formal burial rites. The latter group includes Shanidar 4, the famous ‘flower burial’, so-called because clumps of pollen grains from adjacent sediments were interpreted as evidence for the intentional placement of flowers with the corpse (Leroi-Gourhan 1975; Solecki 1975.1).Figure 1. a) Shanidar Cave as viewed from the south; b) plan of Ralph Solecki's excavations at Shanidar Cave showing Solecki's trench (black grid), the locations of the Neanderthal skeletons he discovered (numbered) and the area of the new excavations undertaken since 2015 (red outline) (photograph by G. Barker, illustration by R. Solecki & R. Lane).

Although the ‘flower burial’ hypothesis was subsequently questioned (Gargett 1999; Sommer 1999.1), the Shanidar individuals play a central role in shaping our understanding of Neanderthal biology and behaviour. The disabling injuries exhibited by Shanidar 1, for example, suggest care for group members, while the puncture wound to Shanidar 3's ribs suggests interpersonal violence (Stewart 1969, 1977; Trinkaus 1983; Churchill et al. 2009; Trinkaus & Villotte 2017). The assemblage continues to feature heavily in debates over Neanderthal mortuary practice and the evolutionary origins of intentional burial, as well as Pleistocene hominin behaviour, diet and morphology (e.g. Gargett 1989, 1999; Smirnov 1989.1; Riel-Salvatore & Clark 2001; Pettitt 2002, 2011; Vandermeersch et al. 2008; Henry et al. 2011.1; Saers et al. 2017.1; García-Martínez et al. 2018; Power et al. 2018.1). Recent evidence for interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans (Green et al. 2010; Fu et al. 2015; Prüfer et al. 2017.2), and the likelihood that this occurred in South-west Asia (Kuhlwilm et al. 2016), bring new relevance to the archaeology of Shanidar Cave.

When the remains of Shanidar 4 were discovered in 1960, the decision was taken to remove them in a sediment block measuring approximately 1m2 and 0.5m deep, encased in wood and plaster. This block was then transported to the Baghdad Museum for excavation (Solecki 1971; Stewart 1977), during which it became evident that at least three adults were represented (Shanidar 4, 6 and 8), along with the vertebrae of an infant—Shanidar 9 (Stewart 1977; Trinkaus 1983). Due to disturbance of the block during transport from Shanidar to Baghdad (on a taxi roof! (Stewart 1977: 155)), the precise stratigraphic relationships between the individuals are unknown. It is clear, however, that Shanidar 4 was the uppermost in a cluster of individuals, suggesting either that multiple individuals died and/or were buried in the same place, or that Neanderthals returned to almost exactly the same spot to deposit multiple individuals (Solecki 1971, 1972; Stewart 1977). Either scenario would offer important, indeed unique, evidence for the complexity of Neanderthal mortuary activity. The detailed relationships between the individuals, and evidence for whether or not they were intentionally buried, however, have been unclear. Over the past five years, a research project has conducted new excavations at Shanidar Cave in order to address some of the questions left unanswered by the previous excavations, including the dates of the Neanderthals, their stratigraphic contexts and the nature of the mortuary activity associated with their deposition.

The new excavations

In 2014, at the invitation of the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq, a project was initiated to conduct the first excavations at Shanidar Cave since 1960. The ISIS threat to Kurdistan, however, delayed the fieldwork, and excavations began in 2015. The eastern side of the Solecki trench where he had found most of the Neanderthal remains (Figures 1b & 2) was re-opened during the excavation. The project's objective was to conduct detailed work at the original trench margins in order to place Solecki's findings into a robust chronological, palaeoclimatic, palaeoecological and cultural framework, using the full range of modern archaeological science techniques that were unavailable at that time. Although we did not expect to find further remains belonging to the Solecki Neanderthals, we needed to establish their probable locations in order to date the sediments in which they were originally found. Solecki was unable to establish their date beyond a terminus ante quem for the upper remains (Shanidar 1, 3 and 5) of around 50 000–45 000 years ago, the then maximum age range of the radiocarbon method. Unexpectedly, in 2015 and 2016, we found several Neanderthal bones, including part of an articulated leg at approximately 5m below the cave floor. Archive photographs and morphological comparisons attribute these articulated remains to Shanidar 5, a male estimated to be 40–50 years old (Reynolds et al. 2015.1; Pomeroy et al. 2017.3). Initial radiocarbon and OSL dates by the University of Oxford (the calculation of some of the OSL dates against background radiation is still in progress) indicate that this individual, along with the other upper Neanderthal remains (Shanidar 1 and 3), date to c. 55 000–45 000 years ago.

Figure 2. a) The Shanidar Cave excavations in 1960, looking north-west. T. Dale Stewart sits excavating Shanidar 4, the central scale marks the location of Shanidar 1 and the white arrow indicates the location of Shanidar 5 (photograph by R. Solecki; Reynolds et al. 2015.1); b) photograph of the new excavations showing the location of Solecki's Neanderthal finds (photograph by G. Barker); c) schematic diagram of the new excavations viewed from the west, showing: the estimated locations of the Neanderthal skeletal remains discovered by Solecki; the locations of the sample columns excavated in the new work; and the locations of the two main areas of open plan excavation (illustration by E. Hill).

From a creationists point of view, not only is the age of these remains an embarrassment but also the fact that they are an ancestral species - one of at least two with whom modern humans interbred - giving the lie to the ludicrously childish fairytale of a single ancestral couple doing naughty things in a garden, then hiding from an omniscient god, who blames us all for the goings on in the garden. We don't even have a single ancestral species, let alone an identifiable couple without ancestors! Genesis is as hopelessly wrong about human origins as it is about the structure and age of the universe, and just about every other aspect of science and history the authors tried to best guess from a position of abysmal ignorance.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.