17,000-year-old skeleton reveals earliest evidence of Stone Age ambush and human conflict | Archaeology News Online Magazine

Towards the end of that immensely long pre-Creation Week period of Earth’s history — when 99.9975% of everything had already happened before creationists believe their god made a small, flat Earth with a dome over it in the Middle East, as described in the Bible — humans were already fighting battles in what is now northern Italy. To be precise, this occurred around 7,000 years before 'Creation Week'.

This conclusion comes from the analysis of a 17,000-year-old skeleton belonging to a man aged between 22 and 30, bearing unmistakable injuries caused by flint-tipped projectiles—likely arrows or spears. The skeleton, discovered in 1973 at the Riparo Tagliente rock shelter in the Lessini Mountains of northeastern Italy, only recently revealed its violent past thanks to modern forensic techniques.

The findings, led by bioarchaeologist Vitale Sparacello of the University of Cagliari, were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The Riparo Tagliente rock shelter and its dating. Location & Description:The discovery and recent reanalysis of the Tagliente 1 skeleton at Riparo Tagliente offers rare and compelling evidence of interpersonal violence - possibly organised conflict - among Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers. Dated to around 17,000 years ago, this individual bears the distinct marks of trauma inflicted by flint-tipped projectiles, likely spears or arrows. While prehistoric violence has long been suspected based on trauma in human remains, this case is among the earliest unambiguous examples of a deliberate ambush-style killing using ranged weapons.

- Riparo Tagliente sits at approximately 250 m above sea level on the east flank of Valpantena in the Lessini Mountains, north of Verona (Grezzana, Stallavena) [1.1].

- This limestone rock shelter spans roughly 15 m in width and up to 4 m in height, with sediment deposits reaching 4.6 m thick [2.1].

- Situated at a crossroads of plains, valley, and rocky slopes, the site offered rich, varied resources—ideal for hunter‑gatherer occupation .

History of Excavations:

- Discovered in 1958 by Francesco Tagliente.

- First excavated by Verona’s Civic Museum of Natural History (1962–64), then taken over by the University of Ferrara (from 1967 onwards) [3.1].

- Systematic annual campaigns have continued, especially in the northern 80 m² area, unearthing thousands of lithics, faunal remains, and human burials [2.1].

Stratigraphy & Occupation Phases:

Riparo Tagliente preserves two major occupation layers separated by an erosion hiatus:

- Middle Palaeolithic (MIS 4–3; Mousterian & Aurignacian) – roughly 60,000–30,000 BP [3.1].

- Upper Palaeolithic (Final Epigravettian) – circa 17,000–10,000 BP, supported by radiocarbon dates between ~16,932–15,495 cal BP and ~14,572–13,430 cal BP [1.1].

Dating Methods:

- Radiocarbon dating was applied to Epigravettian layers (“layer 15”) and produced calibrated ages of ~16,932–15,495 cal BP; upper layers dated at ~14,572–13,430 cal BP .

- The presence of diagnostic lithic industries—Mousterian, Aurignacian, Epigravettian—helps bracket the cultural phases [3.1].

Human Burials & Bioarchaeological Significance:

- A medieval intrusion partially removed an Epigravettian burial in 1973; however, remains from pelvis downward were preserved, belonging to a ~20–29‑year‑old male (~1.63 m tall) [1.1].

- Recent biomolecular work on a femur fragment from Tagliente 1 has used radiocarbon, stable isotopes, and palaeogenomics to link it to other remains (Tagliente 2) from the same site [4.1].

Summary

Riparo Tagliente is a key stratified Upper Palaeolithic site offering:

- A rich sequence reflecting both Neanderthal and later Homo sapiens occupations.

- Robust radiocarbon chronology anchoring the Epigravettian layer to ~17,000–14,500 BP.

- Important genetic and bioarchaeological insights into early post-Last Glacial Maximum hunter‑gatherers in the Italian Alps.

The significance of the site lies not just in the age of the injury, but in its context. The Riparo Tagliente rock shelter in the Lessini Mountains of northern Italy preserves a rich and well-dated sequence of human occupation spanning tens of thousands of years. Layer 15, which yielded the injured skeleton, corresponds to the Final Epigravettian cultural phase—an era marked by regional innovation in stone tool technology and the gradual re-expansion of human populations after the Last Glacial Maximum.

That an individual was targeted and killed with projectile weapons implies more than a moment of personal conflict - it suggests the presence of group-level tensions and potentially even territorial behaviour. This challenges older assumptions that Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer societies were largely egalitarian and peaceful. While cooperation surely dominated daily survival, this evidence shows that violence and strategic conflict were part of the behavioural repertoire of early Homo sapiens.

The analysis also showcases how modern techniques, including micro-CT scanning and advanced radiocarbon dating, can reveal new stories from old finds. The skeleton was first excavated in 1973, but only recently has the cause of death become clear. The ability to revisit and reinterpret older archaeological materials is revolutionising our understanding of prehistory, allowing researchers to extract more nuanced insights from well-curated but under-analysed collections.

Moreover, this case illustrates the cognitive and technological sophistication of Upper Palaeolithic populations. The use of flint-tipped projectiles as weapons implies planning, skill in tool production, and knowledge of anatomy. The ambush setting and targeting of vulnerable areas of the body suggest tactical thinking and possibly coordinated group behaviour - all indicators of complex social dynamics.

In broader cultural terms, the Riparo Tagliente findings paint a picture of a society not just surviving but deeply engaged with its environment and with each other, in both cooperative and conflictual ways. It adds to a growing body of evidence that the Palaeolithic was a time of rich human experience—marked by art, innovation, mobility, and, as this case reminds us, sometimes deadly rivalry.

Technical detail is provided in the team's open access research paper in Scientific Reports:

AbstractThis discovery stands in stark contrast to the claims often made by biblical literalists and young-Earth creationists—that death, violence, and suffering only began after Adam and Eve's supposed disobedience in the Garden of Eden. According to that narrative, the world was a death-free paradise until "The Fall" introduced sin and mortality. Yet here we have clear, scientific evidence of a violent human death that occurred approximately 17,000 years ago—thousands of years before creationists believe the Earth, let alone humans, even existed.

Evidence of interpersonal violence in the Paleolithic is rare but can shed light on the presence of ancient conflict in prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies. Projectile injuries suggest confrontations between groups and have primarily been identified through lithic elements embedded in bones. Recently, the study of projectile impact marks (PIMs) has allowed for the recognition of projectile injuries in the absence of embedded elements. We report here the discovery and study of one of the earliest evidence of PIMs in human paleobiological record, found in the burial from Riparo Tagliente (individual Tagliente 1, Veneto, Italy), directly dated to ca. 17,000–15,500 cal BP. Analyses through SEM and 3D microscopy demonstrate that the femur and the tibia show clear evidence of PIMs impacting the bone from different directions. This could be due to the presence of multiple attackers, or to the victim turning between impacts. No trace of healing is present; one PIM is close to the femoral artery, which can cause a rapid death if pierced. Evidence at Riparo Tagliente could be attributed to conflict between different groups of hunter-gatherers expanding in newly opened Alpine territories during climatic amelioration after the Last Glacial Maximum.

Introduction

Prehistoric skeletal signs of interpersonal violence constitute the most direct evidence for our understanding of the nature of conflict in the past1,2,3,4. Some scholars suggest that in certain prehistoric periods, such as the Mesolithic (in southern Europe around 11.7–8. cal ka BP)2,5,6,7,8, or the Neolithic (in southern Europe around 8.-6. ka cal BP)3,9,10,11, it is possible to detect an increase in the frequency or scale of conflict in the human bioarchaeological record, while others point out similar trauma prevalence since the Upper Paleolithic12,13. In general, diachronic evaluations are likely to be biased by the skeletal record becoming increasingly fragmentary with greater temporal depth. Furthermore, the study of bony lesions is challenging due to technical and interpretative problems: evidence of trauma, when recognized, does not necessarily imply interpersonal violence, and even more difficult is demonstrating conflict between different groups14.

Despite these challenges, certain occurrences allow evidence of violence to be more confidently attributed to external attacks, such as multiple contemporary burials resulting from massacres (e.g.,15,16,17. In addition, wounds caused by projectile weapons – especially when multiple – are strongly suggestive of intergroup conflict2,6,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. In fact, in small-scale, traditional societies, projectile weapons are most often used in raiding and formal warfare, with melee weapons usually employed to dispatch a wounded enemy27,28.

Traditionally, lesions found in the bioarchaeological record were unequivocally attributed to killing at a distance when the projectile remained embedded in the bone. Examples of injuries of this kind in the Paleolithic human skeletal record are extremely rare, with the oldest cases dating to the end of the period, such as Grotte des Enfants 2 (ca. 13,200–12,800 cal BP) 29 and San Teodoro 4 (15,300–14,200 cal. BP)30,31, both from the Late Epigravettian of Italy, Vasilyevka and Voloshskoye from the Epipaleolithic of Ukraine (ca. 12,000 cal BP, although radiocarbon dates for these sites are strongly affected by freshwater reservoir effects and might in fact date considerably younger32,33), and several individuals from the Epipaleolithic cemetery of Jebel Sahaba in Sudan (13,727–7981 cal BP)34,35. Earlier weapon injuries tentatively attributed to projectiles lack embedded elements, as seen in the wound on the first thoracic vertebra of Sunghir 1 from the Gravettian (Russia; 27,700–26,500 cal BP)36,37, and in a rib of the Neanderthal Shanidar 3 (Iraq, 47,000–40,000 BP)38.

Recent advancements in the study of projectile impact marks (PIMs39) have allowed researchers to identify wounds originated by projectile weapons in the absence of embedded lithic elements40,41,42. Smith et al.43 highlighted the challenges in the identification, suggesting that, when flint-tipped projectiles strike bone tangentially, they may produce incised linear defects that resemble butchery marks. Furthermore, they noted that the problematic recognition of those incised linear defects as weapon injuries may explain why projectile wounds in limbs seem to be under-represented in the archaeological literature43,44,45. More recently, experimental research highlighted a series of qualitative and morphometric characteristics of PIMs that discriminate them from cut marks caused by other activities and may have the potential to provide insights into projectile technologies and point typologies39,42,46. In this study, we report the discovery of incised linear defects and other perimortem bony lesions in the lower limb (femur and tibia) of an Upper Paleolithic individual (Tagliente 1) from the Late Epigravettian of Riparo Tagliente (Verona, Italy).

The site of Riparo Tagliente is situated on the left slope of the Pantena Valley in the Lessini Mountains (southeastern Alps, Verona, Italy; Fig. 1A). Excavations beginning in 1962, and still ongoing, unearthed a thick stratigraphic series which includes layers dated to the Mousterian, the Aurignacian and the Late Epigravettian. The latter include one of the most complete Late Paleolithic sequences in northern Italy. The burial Riparo Tagliente 1 was found during excavations in 197347,48 in the southern sector of the site. It was contained in a pit dug into the Mousterian deposits in an area protected by the overhang of the shelter. The stratigraphic analysis allowed the burial to be referred to the first phase of the Late Epigravettian occupation of the site, spanning ca. 17,000–15,000 cal BP49,50,51. Two direct dates carried on the skeleton do not overlap, but are consistent with this time frame (for Tagliente 1: OxA-10672, 13,190 ± 90 14C BP, i.e. 16,126–15,571 cal BP; MAMS 62,622.1.1, 13,491 ± 40, i.e. 16,416–16,096; for Tagliente 2, a mandible found in reworked layers52 attributed to the same individual via genetic analysis53: MAMS-27188, 13790 ± 60, 16,975–16,509 cal BP. All dates report 95.4% probability calibrated using Oxcal v4.4.4)54.

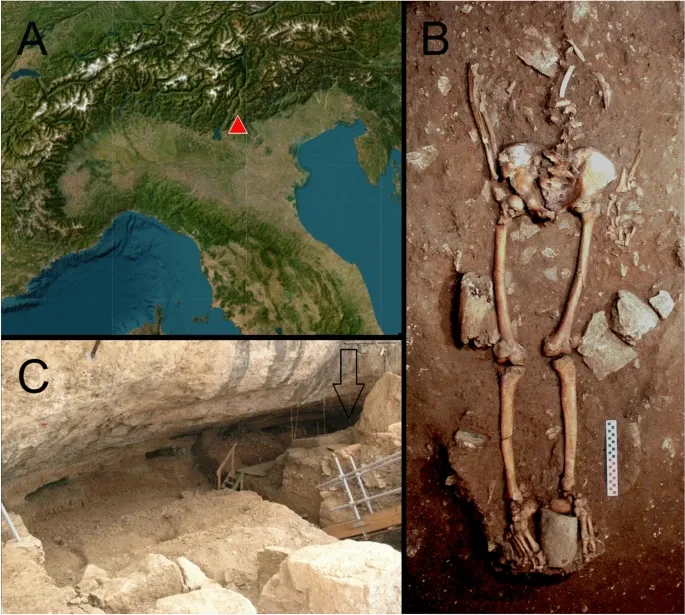

Unfortunately, the excavation of a pit in historical times had disturbed the upper portion of the burial; only the lower limbs, some fragments of lumbar vertebrae and ribs, and part of the right and left forearm were preserved in situ47 (Fig. 1B). However, the disposition of the non-disturbed skeletal elements suggest that the individual was lying supine in a shallow pit, with arms distended on the sides, as typical for Epigravettian burials55,56,57. The skeleton was accompanied by a limestone pebble stained with ochre, and a fragment of a large bovid horn. More uncertain is whether a pierced Tritia shell belongs to the backfill of the pit. Most remarkably, the lower limbs were covered with stone slabs, one of which is engraved with the depiction of a lion and the horn of an aurochs47. The analysis of the pelvic remains indicates that the individual was a young adult male47,48. The circumstances of death were hitherto unknown.Fig.1 (A) The geographic position of the site of Riparo Tagliente in northeastern Italy (map from https://srvcarto.regione.liguria.it/; copyright 2025 Maxar technologies). (B): Zenithal picture of the burial at the time of discovery. (C): The Riparo Tagliente rock shelter; the arrow indicates the position of the burial of the individual Tagliente 1.

(A) The geographic position of the site of Riparo Tagliente in northeastern Italy (map from https://srvcarto.regione.liguria.it/; copyright 2025 Maxar technologies). (B): Zenithal picture of the burial at the time of discovery. (C): The Riparo Tagliente rock shelter; the arrow indicates the position of the burial of the individual Tagliente 1.

Late Epigravettian hunter-gatherers (approximately 17,000–11,700 cal BP) recolonized the southern Alps during the Late Glacial (19.-11,7 ka cal BP). The first and sparse evidence of this recolonization refers to the late phase of Greenland Stadial 2.1 (GS2.1 – 17.-15. ka cal BP) while in the Late Glacial temperate interstadial (GI1e-c – 14.7–12.8 ka cal BP)58 the number of sites increases spanning from Alpine valley-bottoms to highland prairies up to 1,700 mt a.s.l. Although highland sites are mostly attested on the pre-Alpine plateaus (i.e. Lessini, Asiago, Cansiglio, Pradis) some of them reach the inner Dolomites region59,60. Late Epigravettian bands seasonally ascended to high altitudes to hunt medium to large sized game, particularly ibex and red deer, while exploiting valley-bottoms to supply a wider range of resources, including freshwater ones51,61. Projectile technology was widely used, as suggested by lithic and osseous productions42,62,63,64), the presence of PIMs in faunal assemblages42,63 and skeletal adaptations, such as high levels of asymmetry in humeral biomechanical rigidity (e.g.65).

The Late Epigravettian occupation at Riparo Tagliente (from ca. 17,100–16,300 cal BP to 14,572–13,430 cal BP) represents the first evidence in the southern Alps following the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)49,50. This occupation occurred in a context of probable demographic expansion, as indicated by the increase in the number of sites in the following millennia59,60,66,67. While this evidence suggests increasing interactions between groups, the nature of these relationships remains poorly understood.

This study presents evidence that may contribute to shedding light on the nature of intergroup dynamics during this period, focusing on newly identified incised linear defects in Riparo Tagliente 1. Macroscopic, microscopic, and morphometric analyses confirm that these lesions correspond to PIMs. These findings contribute to the limited corpus of early evidence for interpersonal violence associated with projectile weaponry. We will discuss how this evidence is mostly compatible with intergroup conflict, as opposed to within-group or domestic violence.

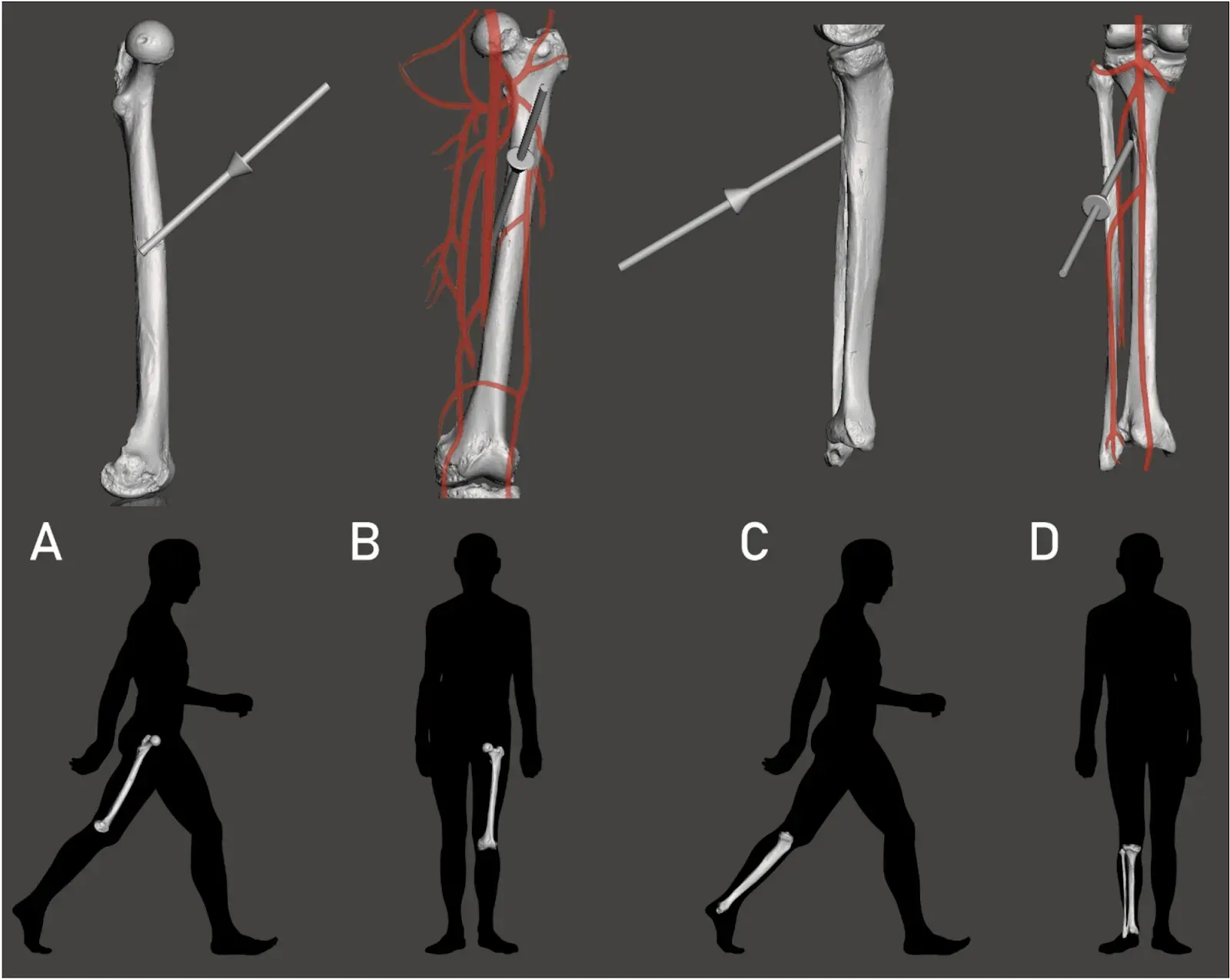

Fig.8 Reconstruction of the probable ballistic trajectory of the projectiles that left the linear marks in Riparo Tagliente 1; In red, the course of the arteries of the lower limb is reconstructed. (A): Left femur, medial view; (B): Left femur, frontal view, showing the path of the femoral arteries; (C): Left tibia, medial view; (D): Left tibia, posterior view, showing the path of the tibial and fibular arteries. (Drawing of the path of arteries modified from: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2129ab_Lower_Limb_Arteries_Anterior_Posterior.jpg#file CC-BY-3.0; silhouettes from Wikimedia Commons CC-Zero).

Reconstruction of the probable ballistic trajectory of the projectiles that left the linear marks in Riparo Tagliente 1; In red, the course of the arteries of the lower limb is reconstructed. (A): Left femur, medial view; (B): Left femur, frontal view, showing the path of the femoral arteries; (C): Left tibia, medial view; (D): Left tibia, posterior view, showing the path of the tibial and fibular arteries. (Drawing of the path of arteries modified from: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2129ab_Lower_Limb_Arteries_Anterior_Posterior.jpg#file CC-BY-3.0; silhouettes from Wikimedia Commons CC-Zero).

Sparacello, V.S., Thun Hohenstein, U., Boschin, F. et al.

Projectile weapon injuries in the Riparo Tagliente burial (Veneto, Italy) provide early evidence of Late Upper Paleolithic intergroup conflict. Sci Rep 15, 14857 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-94095-x

Copyright: © 2025 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

The Tagliente 1 skeleton doesn’t just show signs of accidental trauma or animal predation; it reveals injuries inflicted with intent, likely as part of an ambush using weapons crafted specifically for killing. This isn't the kind of death that could be hand-waved away as a natural consequence of living in a fallen world—it’s the result of deliberate human action, long before any biblical timeline would allow for human existence. The evidence firmly places interpersonal violence deep in the Upper Palaeolithic, not in some post-Edenic moral decline following a mythical Fall.

Moreover, the dating of this burial, anchored by robust radiocarbon methods and stratigraphic analysis, thoroughly undermines the creationist chronology. A 17,000-year-old death predating even the oldest biblical estimate of creation is more than a chronological inconvenience—it is a fundamental contradiction. For those who claim the Bible is a literal historical document, this single skeleton poses a profound problem: it shows that real humans were living, hunting, dying—and killing—long before the alleged dawn of history in Genesis.

In essence, the Tagliente 1 skeleton is a silent yet eloquent witness against the notion that the world was once perfect and untouched by death. It is physical, datable, and scientifically verifiable evidence that contradicts the central tenet of young-Earth creationism—that death entered the world only through human sin. Instead, it aligns squarely with evolutionary history: a long, often harsh prehistory shaped by natural forces, environmental pressures, and all-too-human behaviours, including violence.

Advertisement

All titles available in paperback, hardcover, ebook for Kindle and audio format.

Prices correct at time of publication. for current prices.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.