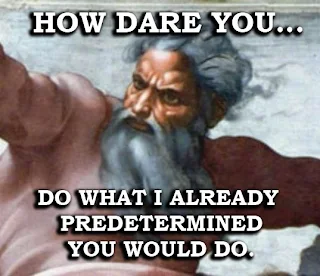

Despite my blog exposing the logical fallacy of an inerrantly omniscient god and free will, it seems the full implications of this have gone unnoticed by many.

Let’s recap:

We are discussing the god of the Bible which Christians, Jews and Moslem all regard as omniscient (all-knowing) and whom they believe has granted mankind free will.

Following from this is the idea that, by exercising this free will, mankind committed the ultimate sin of disobeying God and must now seek God’s forgiveness. God does not pre-ordain our decisions so we bear sole responsibility for our own actions and are accountable to God for them. At the same time, God is all knowing and inerrant and so knows everything with absolute certainty. He knows everything about the past, present and future and is never wrong, ever.

Christians, Jews and Muslims and their various sects all believe they alone know the special secrets for gaining this god’s forgiveness for this supposed supreme sin of disobeying God. The only way to achieve this is by joining them, accepting their dogmas and following their rituals.

Furthermore, mankind knows about this sin, about God’s inerrant omniscience, about mankind’s free will and about the need for forgiveness, because it’s all written down in a book either written by, dictated by or inspired by this inerrant (and perfect) god, so it too is inerrant and absolutely true.

Surprisingly though, a simple question which can be answered with a simple “yes” or “no” answer seems to put Christians, Jews and Muslims all into the same flat panic.

The simple question is:

If God has always known what you will have for breakfast tomorrow, can you choose to have something else instead?

So what exactly is the problem here?

Let’s consider the possible answers:

Answer 1. Yes.

Ah! Then something can happen that God didn’t know about, so God is not omniscient or inerrant. God got it wrong, and god didn’t know your eventual choice.

And the Bible is wrong about the god described in it.

Oops!

Answer 2. No.

Ah! So you can't chose to do something other than what God has known you’ll do, and had known for ever that you’ll do, even from before he (so it is believe) created you.

In that case, God’s inerrant omniscience means you don't have free will and your actions have all been pre-determined for you by God’s prior knowledge of your actions. In effect, you are no different to an automaton.

And, as a mere automaton of course, you can’t be held responsible for you actions. Accountability lies with the person controlling you – which is er... God.

And that means all this stuff about human disobedience, sin and needing to beg God for forgiveness is wrong.

Oops!

So how to resolve this paradox?

Well, we could always argue that this God isn’t actually inerrantly omniscient. That restores human free will and our accountability for our own actions, but where does it leave God?

It leaves God as someone who is less than perfect, who makes mistakes and doesn’t actually know everything. In fact, it makes God unfit to judge us humans and condemn us for making mistakes, being less than perfect and not knowing everything. In fact, it places God on an equal footing to humans.

Perhaps there are Christians, Muslims and Jews who can accept that, but where does it leave the Bible?

The Bible is no longer the inerrant word of an omniscient god. In fact it’s wrong on at least one, if not both, the central tenets of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. It’s either wrong about the nature of God, or about human free will, or both. Moreover, the moral judgement of the god described in it is now in question. This god has apparently judged humans to be sinful when it is also capable of doing wrong. Let him who is without guilt cast the first stone.

The Bible is no more reliable as a guide to truth and morality than had it been written by mere humans, (which of course is precisely who wrote it and why it can be safely dismissed as a guide to truth and morality).

Clearly there is no satisfactory way to resolve this problem.

And the entire foundation of three major world religions has just collapsed under its own internal contradiction. The thread upon which the whole edifice dangled has just vanished, if you'll excuse a slightly mixed metaphor.

And, when you ask a Christian, Jew or Moslem that simple little question, requiring a simple yes or no answer, you will quickly discover that either they have never thought about the central tenets of their ‘faith’, or they are only too well aware of the lie at the heart of it. They will either blunder into an answer, and then squirm as you point out the implication of it, or, much more likely, they will wriggle and squirm and do anything but give an honest answer.

A very nice example of this can bee seen at Chirpstory - Christian Dishonesty where a fundamentalist Christian starts off confidently answering a question until he realises where it's leading, then nothing will induce him to give a straight yes or no answer to a simple question. Clearly he knows whichever answer he gives will expose the lie he knows exists at the very heart of his 'faith'.

These latter ones are the ones who are well aware that their professed ‘faith’ is a lie. These will usually be the ones who are actively trying to persuade others into believing something they know to be false. These will be those proudly pious people who make smugly condescending pronouncements about the shortcomings of others and about their special relationship with God and how this gives them a short-cut to knowledge which is unquestionably superior to that gained through diligent learning and reason. They may also be the priests, pastors, preachers, clerics, rabbis, imams and other snake-oil salesmen who have a vested interest in trying to control you through the fear and superstition they themselves know to be untrue.

These will be the ones claiming to know the magic spells, rituals and incantations which will help you gain this god’s forgiveness; a forgiveness they know to be unnecessary for a guilt they know to be unjustified from a god they know does not exist.

This central logical contradiction at the heart of all the Abrahamic, guilt-based religions betrays their human origins and the desire to exert control over others which motivated them.

And it takes only a simple little question to expose the many charlatans who feast off the opportunities it creates for controlling others and the many phoney pious Christians, Muslims and Jews who know their 'faith' is a lie but none-the-less continue to piously profess it because it allows them to pose as superior to the rest of us.

These morally bankrupt Atheists (for that is what they are) are a disgrace to humanity. As a fellow Atheist I am ashamed of them and their moral degeneracy. As a human being I am angry at the harm they've done to people, to human culture and to the societies they've perverted for their own nefarious purposes.

We can be better than that. For the sake of humanity we should do better than that.

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

God is all-knowing but does not force our hand. We still have free will and the ability to chose for ourselves who we will serve and although He knows what we will decide He allows us to make that choice, right or wrong. Free will and the omnniscience of God are not in contradiction to one another.

ReplyDeleteJohn 3:16 For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten son that whosoever believes in Him will not perish but have everlasting life.

You weren't able to give a simple yes or no answer to that simple question, then?

ReplyDeleteSo, now we know you know your 'faith' is a lie beyond any reasonable doubt, would you care to tell us who you're hoping to fool with your preaching, and why you want to persuade them to believe something you know to be false?

Most people of "faith" consider belief in impossible things to be a net positive. They delight in it, because to them, overcoming doubts is a victory over Satan who is the one responsible for making the whole thing look impossible, sowing the seeds of doubt and disbelief.

ReplyDeleteWith that type of reasoning, you can't win.

There are so many things in the bible/quran/torah which are just flat out impossible. The classic is "Can God create a stone so heavy that God can't move it", which shows the basic impossibility of omnipotence, but to the true believer it isn't a disproof at all, it is just something to ponder to "bring him closer to God". Mankind has wasted thousands of years thinking about such things.

Sometimes I despair

Excellent work Rosa. Wish "they" would even ponder some of what you/I/we say on such matters.

ReplyDeleteHello Rosa,

ReplyDeleteIt is a strange reality that often atheists are more theologically educated than many theists. Likewise, it is amazing how many theists fall right into line with straw-man stereotypes of theistic ways of thinking.

I must take issue, though, with your conclusions in this article not because there are Christian and Muslim theists in abundance who actually exhibit variegates of your characterizations above but because there are other perspectives that escape this omniscience-free will-and theodicy trap.

Note: I am not a theist. I am somewhere between atheism and transtheism but a thorough humanist and skeptic. However, as stated, there are other theistic models aside from the strict predestination-model of divine sovereignty.

For example, open theism posits a God with limited knowledge of the future (a limitation that is either of God's volition or ontologically related to what can be known). In this model humans have complete free will and can do and behave in ways that might surprise even God. In open theistic models, God might be said to know all possibilities in advance but not to know the actual events until they transpire.

It is worth noting that most open theists are Evangelicals and believe in a inerrant Bible. That is, they have developed theological hermeneutics that do not confine their exegetical endeavors to strict predestination and foreknowledge. Frankly, I find their exegetical assumptions to be far more congruent with sound historical-critical hermeneutics than the post-Augustinian and hellenistic assumptions of classical theism.

Another model which is far less concerned with the Bible is process theism, but I will stop for now at this.

Thanks for that thoughtfull contribution.

ReplyDelete>It is a strange reality that often atheists are more theologically educated than many theists.<

In my experience, that's often why Atheists are Atheists.

>For example, open theism posits a God with limited knowledge of the future (a limitation that is either of God's volition or ontologically related to what can be known). <

I must confess I'm puzzled about how a god can voluntarily not know something. How can it do so without knowing what to volunteer not to know? It must know in advance what to choose not to know.

Hey Rosa,

ReplyDeleteClassical theism is stuck in Hellenistic/Greek ways of thinking that make it incumbent on all-powerful creator to know all and be transcendentally all powerful. In the Hebrew Bible the deity is far more mundane--often expressing surprise and limited knowledge in the face of human affairs. Later Jews and Christians now call these biblical events literary devises or anthropomorphism, but it is far from likely that the original Hebrew readers of these texts would have seen them as such.

There are several models of open theism and process theology, but all posit limited knowledge of the future on the part of the deity. There is too much stuff to say on this...so I'll leave it here. But, I just want to illustrate that their are theistic permutations that leap the hurdle of classically-defined omniscience and free will.

peace!

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteThe simple answer to your dilemma is "Yes." But the consequence you draw -- that "God got it wrong" -- does not follow. It would follow if your question had been a slightly different one: "... will you choose to have something else instead?" The proper answer to that question would be "No."

There is a substantial literature on modality, choice, and omniscience. It might be a good idea to have a look at it before assuming that everyone who maintains the compatibility of omniscience and free will is a charlatan who can be exposed by a simple question like this.

Er... no. It follows from that answer that God can be wrong; that you CAN do something God didn't know you would do.

ReplyDeleteI'm familar with the usual standards of theology in which the outcome is pre-determined then the 'logic' is built around the desired answer with any amount of bending permitted until the right conclusion is reached.

Theology, in other words, is a carefully constructed workaround or a skilled avoidance of the obstacles with which religion needs to cope.

"Er... no. It follows from that answer that God can be wrong; that you CAN do something God didn't know you would do."

ReplyDeleteSorry, but actually, it does not follow. You will do X. God knows (and has known) that you will do X. You are free to do Y instead of X. But if you were to do Y, then it would have been the case all along that God knew that you would do Y. No contradiction emerges at any point.

You can complain, if you like, about omniscience; you can argue that no being could have that kind of knowledge. But you cannot generate a contradiction from the mere combination of freedom and foreknowledge.

In fact, it's important that you not be able to, since otherwise anyone's knowledge of the past would render people's actions unfree by parallel reasoning. "I know that, in point of fact, he took the train. Could he have taken the bus instead?" etc. The argument works in both cases or in neither. In this case, it's neither.

Just found this blog after linking to it from apologetics 315. I like how you are thoughtfully considering these issues. It's sad that more of my fellow Christians don't think about these things. However, I disagree.

ReplyDeleteTim is 100% correct. This assumption that somehow free will and omniscience are in conflict is based on a fundamental modal fallacy.

This mode of thinking works out like this:

1) Necessarily, if God foreknows x will happen, then x will happen

2) God foreknows x will happen

3) Therefore, necessarily x will happen

which would take the form:

□ P -> Q

P

___

□ Q

But this reasoning is fallacious. All that would actually follow from the premises displayed is Q. In terms of God's foreknowledge, all that would follow is that x will happen, not that necessarily x will happen.

That means that something other than X COULD have happened. But as Tim rightly says, if something other than X will have happened due to some free choice, then God would have known that.

In other words, God knows the free choice itself. That doesn't have any bearing on what free choice is made.

No. The question was as I stated it. What you and Tim are doing is not answering it and adopting the coping strategy of complaining I should have asked a different one, then weaving an ellaborate rationalisation for so doing.

ReplyDeleteIt's a simple question, requiring a simple yes or no answer, concerning what we could or couldn't do (not will or won't do) in the hypothetical presence of an inerrantly omniscient god.

Can you choose something other than what an inerrantly omniscient god has always known you choose (and the god still remain inerrantly omniscient)? Yes or No?

I note that neither you nor Tim answered the question...

Tim. I have removed your abusive post. Please confine your comments to dealing with the subject of the discussion in a polite manner.

ReplyDeleteRosa,

ReplyDeleteRosa,

I am sorry that you felt moved to remove my post; the part to which you objected was merely a request for you to temper your language, and it was, I think, more moderately phrased than your own. Nevertheless, as this is your blog, I will simply repost the key content:

You write:

"I note that neither you nor Tim answered the question... "

The first line of my first post, timestamped 14 November 2010 18:57, reads:

The simple answer to your dilemma is "Yes."

It's stacking the deck to demand an answer phrased as you want it, as certain explanations call for more nuance than just "yes" or "no".

ReplyDeleteNo. It's not giving a straight answer to appear to answer it but immediately disclaim the answer by complaining that I hadn't asked that right question, with the implication that your answer was for that question instead.

ReplyDeleteYou have, as I said, merely demonstrated your attempt to rationalize your avoidance of something you know to be untennable - the holding of two mutually exclusive opinions simultaneously.

The fact that you know you need to do that betrays the fact that you know that your 'faith' hangs on a non-extent thread.

bossmanham. No. It's a perfectly valid question requiring only a simple yes or no answer.

ReplyDeleteThat fact the you know you need to make an excuse for not answering it shows a great deal, as my blog has already explained. Shame you didn't read it all before rushing out your excuse.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYou asked a question:

If God has always known what you will have for breakfast tomorrow, can you choose to have something else instead?

And I answered the question straightforwardly: Yes.

There is nothing evasive about this.

The problem arises when you try to draw a conclusion from this answer:

Then something CAN happen that God didn’t know about, so God is not omniscient or inerrant. God got it wrong, and god didn’t know your eventual choice.

This conclusion, as both bossmanham and I have pointed out, does not follow from an affirmative answer to your question as you phrased it. The illusion to the contrary depends on a scope error in modal logic, confusing the necessity of the consequence,

□ (P -> Q),

with the necessity of the consequent,

(P -> □Q)

Now you write:

It's not giving a straight answer to appear to answer it but immediately disclaim the answer by complaining that I hadn't asked that right question, with the implication that your answer was for that question instead.

You are mistaken. My answer was for your question as you asked it. What I went on to point out is that only an affirmative answer to a different question would have the consequence you drew -- but that, to that different question, the proper answer would be "No."

You have quite reasonably requested that we deal with the subject of the discussion in a polite manner. You have now in this thread accused me of adopting "a coping strategy," weaving "an ellaborate [sic] rationalisation," and acting in bad faith. For clarification only: Are these examples of polite discussion that we are free to emulate if we believe that you have acted similarly, or would the use of such language by us toward you result in the deletion of our posts?

So you can do something God didn't know you would do and thereby NOT do something God thought you would do, but this doesn't make this god errant nor change its omniscience.

ReplyDeleteAnd black can be white when you need it to be to sustain a claim that everything is white...

I guess that why fewer and fewer people are taking theology and the superstition it's designed to defend, seriously.

Don't you ever wish you had something logical to defend?

"So you can do something God didn't know you would do ..."

ReplyDeleteCan, yes. Will, no.

"... and thereby NOT do something God thought you would do."

Nope; this doesn't follow.

You seem to be having difficulty seeing this when it is stated in ordinary language, so here's the technical version. In the standard semantics for modal logic, one indexes propositions in terms of possible worlds. Here's a simple model-theoretic argument, using the standard modal system S5, to show the consistency of omniscience with freedom.

Let P = Tim will eat (only) a pop-tart for breakfast;

Let T = Tim will eat (only) toast for breakfast;

Let G(X) = God knows that X;

Let ◊X = It is possible that X.

Now, in w1, the actual world:

P

G(P)

~T

◊T

This is a consistent set. Any contingent claim like T is possible even in a world in which it is false.

In virtue of the fact that T is possible in w1, there is some world accessible to w1 -- call it w2 -- in which T is actually true. But that world need not be w1. And there is absolutely no constraint that would license the inference from the fact that G(P) is true in w1 to the conclusion that G(P) is true in any world other than w1. The only constraint imposed by omniscience is that, in any given world, if a proposition is true, then, in that world, God knows that proposition; whereas if, in that world, a proposition is false, then, in that world, God does not believe that proposition. Since P is true in w1, G(P) is true in w1. Since P is false in w2, G(P) is false in w2.

In w2,

T

G(T)

~P

◊P

Once again, this is a consistent set.

So, contrary to what you keep asserting, there is no contradiction.

Tim. If you do something OTHER than what God KNEW you would do then God can't be inerrant and if God didn't know what you were going to do, God can't be omniscient. No heap of verbiage can hide that simple logic. If you think you've come up with a logical construct which does then your construct is wrong.

ReplyDeleteWe both painted for you the simple logic that proves you wrong. But if you formulate your worldview around logical fallacies, then I'm not surprised you're an atheist.

ReplyDeleteI'm more than happy for others to judge the relative merits of our arguments.

ReplyDeleteAll I would point out is that if your 'logic' appears to show that observable reality is wrong, then your logic is at fault, not reality, no matter how much you wish that were not so.

Neither bossmanham nor I has any gripe with observable reality. We just don't feel moved to roll over in the face of faulty logic.

ReplyDeleteWell, I suppose if you're determined to believe there are things God can be wrong about and yet he is still inerrant; and there are things he doesn't know yet he is still omnicient; and if you imagine you have devised a 'logic' which 'proves' that, there is probably little point in continuing this discussion. We obviously have different standard of logic. I don't use 'theologic'.

ReplyDeleteRosa,

ReplyDeleteNobody here is using "theologic." Modal logic is a major subfield of logic with a large literature -- and no, it was not invented by wild-eyed fundamentalists in order to safeguard their beliefs. You might want to have a look at standard texts like Hughes and Cresswell or Garson.

The key point you are missing is that God's foreknowledge is contingent on what you will, in fact, freely choose to do. It isn't a prediction or an educated guess. As I said right at the outset, you may wish to challenge the idea that there could be a being with knowledge like that. But this would be a very different discussion.

Your description of our position -- "there are things God can be wrong about and yet he is still inerrant" -- shows that you are still in the grip of your original error. Nobody in this conversation is maintaining that God can be both wrong and right about the same thing in the same sense at the same time. It doesn't further discourse about these topics when you repeatedly fail to understand what it is that your dialectical sparring partners are saying.

Tim. When you're reduced to arguing that black is white and having to hide it under an increasing tangled heap of verbiage, my advise is that it's time you called it a day.

ReplyDeleteYou may, of course have the final word...

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteThe trouble is that you haven't established any such thing: you just keep reasserting dialectical victory without engaging with what bossmanham and I are saying. Simply calling our responses a "tangled heap of verbiage" doesn't make it so. I can't see that you have made any effort in this entire discussion to understand the position that you are critiquing.

In this world, now, there is something you're going to eat for breakfast tomorrow. You and I may not be sure, now, what it is. But if I say now, "Rosa is going to eat an egg for breakfast tomorrow," and you are, in fact, going to eat that egg, then I am speaking truly now. For the sake of the argument, let’s suppose that this is, in fact, what you are going to eat. Call this the principle of future facts, FF for short.

If you are, in the libertarian sense, free either to eat the egg or not to eat the egg tomorrow, then you have a genuine choice: you can choose not to eat the egg. This is logically possible and causally possible: there is no inherent contradiction in saying that you will not eat an egg for breakfast tomorrow, and it does not violate the causal conditions already in place; you are not constrained to eat that egg. Call this the principle of free choice, FC for short.

Suppose you don’t.

That supposition is an invitation to consider a world that is a bit different from our own. For in our world, as we stipulated at the beginning, you are, in fact, going to eat that egg for breakfast tomorrow. But since your not eating the egg tomorrow is logically possible, we can contemplate the alternative. In that world, if I say, now, “Rosa is going to eat an egg for breafast tomorrow,” then I am speaking falsely now.

There is an old argument for fatalism that takes FF and FC as its starting points, the intention being to argue against FC by reductio ad absurdum. “For,” so runs this argument, “if you were to do something other than what you in fact do, then it is both true (by FF) that you eat an egg for breakfast tomorrow and false (because you don’t) that you eat an egg for breakfast. But this is impossible. Therefore, FC is false—you do not actually have free will.”

This is a defective argument. There is no actual contradiction and, therefore, no ground for the reductio.

But the defect in this argument for fatalism is essentially the same as the defect in your argument against the compatibility of foreknowledge and freedom.

What went wrong in the argument for fatalism?

ReplyDeleteThe problem lies in a misunderstanding of FF. The principle does not say that if it is true now that Rosa will eat an egg for breakfast tomorrow, then this is true now whether Rosa eats that egg or not. The present truth value of that claim is contingent on what Rosa chooses to do tomorrow. If, tomorrow, Rosa chooses to eat that egg, then it is true today that Rosa will eat that egg tomorrow. If, tomorrow, Rosa chooses not to eat that egg, then it is true today that Rosa will not eat that egg tomorrow.

Once we clear this up about FF, there is no contradiction. To put it in the language of worlds, in a world where, tomorrow, Rosa chooses to eat the egg, it is true now that Rosa will eat the egg tomorrow; in a world where, tomorrow, Rosa chooses not to eat the egg, it is true now that Rosa won’t. But a contradiction would arise only if there were a conflict between what is true now—including that future tense statement about what Rosa will do—and what Rosa does tomorrow. In neither world does such a conflict arise. This is why the argument for fatalism fails.

The parallel problem with your argument should now be clear. What God knows about your future actions is contingent on what you choose to do tomorrow. God’s beliefs are not guesses, even educated guesses: God sees the future as it will in fact be. Among other things, therefore, God sees your breakfast tomorrow and knows, directly, what you choose to eat. If you are going to choose that egg, God knows now that this is going to be your choice. If you are going to choose not to have the egg, God knows now that you will decide against it. In neither case does God know something false.

So basically then, cutting through the virbiage, your argument is that, if I had asked a different question, you could have given the answer you like and so show that black CAN be white when you need it to be, therefore I must have asked the wrong question.

ReplyDeleteBut that WASN'T the question I asked.

Why not answer the one I DID ask?

No, that isn't my position at all. It appears that you're ignoring what I've actually written and assuming that your initial, mistaken impression must be right.

ReplyDeleteOnce more, for the record: I did answer the question you asked -- in the very first line of my first post on this thread. The answer is "Yes."

But as I have now explained several times, it doesn't entail what you think it does -- and a good thing, since if it did, then a parallel line of reasoning would eliminate free will without any need to bring in the existence of an omniscient deity.

Except, of course, that free will is ONLY eliminated in the presence of an inerrant, omniscient deity, because it's that presence which eliminates it by inevitable pre-ordaining everything by it's inerrant, omniscient nature.

ReplyDeleteOops!

Ahh, "eliminated."

ReplyDeleteBut it's not; the assumption to the contrary amounts to the assumption that you have presented a sound argument for this conclusion. And that is the very point in dispute. So your reiteration of this claim is simply begging the question.

Tim. Since it's very clear now that you are unable or unwilling to believe that the conclusion of your 'logic' can possibly be anything other than the one you require, there really seems little point in continuing this conversation. I'll leave you with your evidently unshakeable belief in your ability to change the facts at will to suit your requirements.

ReplyDeleteRosa,

ReplyDeleteI'm sorry that you are unwilling to engage with substantive criticism of your argument. It is somewhat frustrating to write long, irenic posts answering your initial question and explaining why your conclusion does not follow, only to have those explanations ignored as "verbiage" and to be falsely and repeatedly accused of not having answered your question. As you say, readers will be able to judge for themselves the merits of our respective positions.

As I noted earlier, there is a substantial literature on the logical analysis of foreknowledge and free will as well as related puzzles regarding the truth values of future tense contingent claims. If you ever want to find out what thoughtful theists (and even thoughtful atheists) think about these topics, it's there and waiting to be explored. I would recommend:

* Augustine, De Libero Arbitrio, Book 3

* Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica Ia, 14, ad 3

* William Rowe, "Augustine on Foreknowledge and Free Will," Review of Metaphysics 18 (1964), pp. 356-63

* Nelson Pike, "Divine Omniscience and Voluntary Action," The Philosophical Review 74 (1965), pp. 27-46

* Richard Taylor, "Deliberation and Foreknowledge," in Bernard Berofsky, ed., Free Will and Determinism (New York: Harper and Row, 1966), pp. 277-93

* Anthony Kenny, "Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom," in Kenny, ed., Aquinas: A Collection of Critical Essays (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1969)

* J. R. Lucas, The Freedom of the Will (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970)

* Alvin Plantinga, God, Freedom, and Evil (New York: Harper and Row, 1974)

* Nelson Pike, "Divine Foreknowledge, Human Freedom, and Possible Worlds," Philosophical Review 86 (1977): 209-16

* Richard Swinburne, The Coherence of Theism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), chapter 10

* Stephen T. Davis, Logic and the Nature of God (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983), chapter 4

* William Lane Craig, Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom (Leiden: Brill, 1991)

* Linda Zagzebski, "Foreknowledge and Free Will," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2008

In addition to what you've talked about, the notion of free will as a stand alone concept is problematic. All decisions are made by our brains. Our brains are physical in nature and are governed by the laws of physics.

ReplyDeleteSo two choices. If quantum effects play no role in our brain, then its future state is a function of the previous state. We may not be able to predict it, but it's set nonetheless. It's a "mindless" system so to speak.

If quantum effects DO play a role, then an element of randomness is introduced which again is beyond the scope of "free will" since "free" implies deliberation and not a randomness.

So simple!

Aparently, brain-scan experiments have shown that our brain makes a decision 200 milliseconds before we become consciously aware of taking it.

ReplyDelete(Benjamin Libet)

I loved this blog. Points made are completely valid. question: if God creates a someone, knowing that he'll murder someone some day, isnt that more like setting a train on a set of tracks? The tracks defined by God himself when he chose to create you. If God didnt want you to murder that person, could he not just have chosen NOT to create you? What about the murdered person? Doesnt creating someone you know will be murdered by someone else evil? free will and an omniscient God are mutually exclusive.

ReplyDeleteFor me, existence itself (assuming an omniscient God exists) is a statement of intent by God. If you say God is omniscient, but allows you to do what you will, that chain of thought is nullified by creation itself, because God can choose to create you in a different way, where you wont make the same choices. So the choices you make now, are the ones God prefers you make. Free will? i dont think so.

ReplyDeleteI don't see this as the simple yes or no question you make it out to be. I see a trick question that attempts to create a logical contradiction by asking God to "know" and "not know" at the same time. The question is nonsense, and C. S. Lewis rightly pointed out, that nonsense doesn’t acquire sense and meaning simply by attaching God to it.

ReplyDeleteExpecting simple yes or no answers to questions that don't have one is not fair. How about this simple yes or no question. Do you still beat your spouse?

I'm sorry you don't see it as a simple yes or no question when it very clearly is. I'm at a loss to know how to explain that a question which asks if you can do something can be answered with a simple yes or no if you are unable to see that that is so.

ReplyDeletePerhaps you could point out where the false assumption is which would make it a 'Do you still beat your wife?' type of question, please.

Perhaps you are assuming that the 'if God knows' clause is a false assumption. If so, then you have no need to try to rationalise the rest of the question away to avoid answering it.

No. It is NOT a simple yes or no question, which was the point of the "Do you still beat your spouse question?" type question. You can't answer yes or no, unless you actually beat your spouse, but that's not the point. I'm making the assumption that you don't.

ReplyDeleteThe question can't be answered with a simple yes or not, because it sets up a paradox, one that actually has a name (Omnipotence Paradox).

See:

http://skepticwiki.org/index.php/Omnipotence_Paradox

and:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omnipotence_paradox

Finally, failure to answer a "simple yes or no" question does not constitute proof of anything. It only proves that the correct answer isn't known.

Perhaps it escaped you but I didn't actually ask if you were still beating your wife. I asked if you could choose something else for breakfast. That, self-evidently, can be answered with a simple yes or no; either you CAN choose something else, or you can't.

ReplyDeleteThe fact that you're performing these intellectual summersaults to avoid answering it shows me that you know you must avoid answering it at all costs, even at the cost of your own intellectual integrity.

And that, I think, proves my point very nicely.

No, you can't change your mind, but not for the reason you suggest.

ReplyDeleteFirst: You Can't Change Your Mind

To clarigy, we comparing two different periods of time: breakfast tomorrow (sometime specific) and choosing something else (prior to sometime specific).

One: If God has always known what you will have for breakfast tomorrow,

This is referring to a final decision you are going to make at a specific point in time. When that specific point in time (breakfast tomorrow) arrives, you will make a final decision (what you will have). Once you start filling your face with oatmeal, toast, Wheaties, whatever, and finish, you've made your final decision (what you had). If God has always known your final decision, then, God has always known what you will have for breakfast tomorrow.

Two: can you choose to have something else?

Prior to breakfast tomorrow, you can change your mind a million times. Once you reach that specific point in time (breakfast tomorrow), and make your decision (what you will have), you won't be able to change your mind anymore. "What you will have" will become "What you are having," which leads to "what you had." At some point during that process you made a final decision about what you will have for breakfast, and had it.

You can't go back in time, therefore, you can't choose to have something else.

Second: Conclusion Against Free Will

The question itself is misleading, because by placing God's knowledge into it, it creates the idea that God is responsible for your ability to choose or not choose. As I pointed out, this is false. In addition to that, the term "known" is ambiguous. If we rephrase the question, and clarify "known" we get:

Q1. If God has always known (predetermined by Him) what you will have for breakfast tomorrow, do you have free will?

A1. No. If God had established or decided in advance your final decision, and you had no choice in the matter, then you DO NOT have free will.

Q2. If God has always known (foreknowledge of your choice) what you will have for breakfast tomorrow, do you have free will?

A2. Yes. Even though God had awareness of your final decision before it was made, as long as your final decision was yours, you DO have free will.

So, to summarize:

Q. If God has always known what you will have for breakfast tomorrow, can you choose to have something else?

A. No, because you can't go back in time. God's knowing in advance is irrelevant to the question.

Now that's pretty darn clear.

Nonsense. I don't decide in advance what I will have for breakfast tomorrow. I decide at the time, there and then.

ReplyDeleteYour attempt at the necessary mental gymnastics to avoid the question was amusing though.

Can you tell me how you knew you needed to perform them?

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteYou've accused me of avoiding the question which makes it clear that you didn't read what I wrote. Please read it again, and then answer this question. A simple yes or no will suffice.

ReplyDeleteYou said: "I decide at the time, there and then."

Can you change you mind once you decide?

If you read the question you will see it asks if you can choose something other than what God has always known you will choose, not whether you can change your mind.

ReplyDeleteHow about dealing with THAT question instead of avoiding it by making up a different one to attack?

Or is there a problem?

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI've already dealt with THAT question. See the section "So, to summarize:" from my 13 January post.

ReplyDeleteYou seem to be trying to avoid any discussion of the question that may take you outside of your preconceived conclusions. Why is that?

You know what? I'll play by your rules.

ReplyDeleteNo. You can't choose something other than what God has always known you will choose.

So why does the Bible lie about mankind having free will, and where does that leave the notion or original sin and the need for redemption and salvation, and the reason for Jesus?

ReplyDeleteIn fact, of course, it renders the entire basis of the Christian, Jewish and Moslem religions null and void.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteAs I've already shown, the consequence you want to draw does not follow from the premises. And a good thing too, or else it would follow simply from the fact that future-tense statements about your free actions have truth values now. Fortunately (for human freedom), the inference is simply invalid.

I have spelled this out using modal logic, I have explained it verbally, and I have given you a guide to the extensive literature discussing this subject.

If you are interested in pursuing this at a level beyond merely repeating what you started with, do let us all know.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteDo you know the difference between foreknowledge and predetermined?

Jeff

Tim. No. What you've shown is that, if you are inventive enough and prepared to abandon any pretense of personal integrity, you can find a workaround for this problem that you can convince yourself deals with it.

ReplyDeleteI think most intellectually honest people would prefer not to have to go to those lenghths just to retain an infantile self-delusion.

Alan. Yes.

ReplyDeleteAre you going to explain why you needed to pretend I had asked a different question rather than answering the one I actually asked?

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteI'm sorry you're not up for the critical examination of your own ideas. It's something that both theists and atheists would do well to cultivate. But representatives of both sides of the debate seem to prefer to stand pat and repeat their talking points instead of engaging in the give-and-take of argument.

Are you going to explain why you needed to pretend I had asked a different question rather than answering the one I actually asked?

ReplyDeleteOnly if you explain why you need to pretend I didn't answer it.

Since you know the difference between predetermined and foreknowledge, then would you agree with both of the following statements?

- If someone has predetermined your actions, they have made your choices. You lose the ability to choose for yourself.

- If someone has foreknowledge of your actions, they know of your choices. You retain the ability to choose for yourself.

Are you now saying you CAN choose something other than what God has always known you'll choose?

ReplyDeleteOkay.

So why did God lie when he claimed to be omniscient and inerrant?

You didn't answer the question.

ReplyDeleteThis discussion isn't really about finding the right answer is it? It's about finding Rosa right.

Am I wrong?

No. It's about showing people the lengths religious people need to go to to maintain their god delusion by avoiding difficult questions at all costs. And thank you for helping with that.

ReplyDeleteSo, now you've given two diametrically opposed and mutually exclusive answers to the same simple yes or no question, would you like to go for a tie-breaker?

You still haven't answered my question.

ReplyDeleteThe fact that you're performing these intellectual diversions in order to avoid answering my question "shows me that you know you must avoid answering it at all costs, even at the cost of your own intellectual integrity."

You're still pretending not to have read my answer, just as you're pretending to have answered my original question.

ReplyDeleteThe great thing is that you're doing EXACTLY what I predicted you would do, knowing, as you undoubtedly do, that there is a lie at the heart of your 'faith' which you must avoid confronting at all costs in order to maintain your delusion.

The only possible explanation for this bizarre behaviour is an irrational phobia. The technical term for this particular one is theophobia.

No doubt you would proudly describe yourself as 'godfearing' without the slightest sense of irony.

Wow.

ReplyDeleteIt is simple.

ReplyDeleteThere are two states for God. Omniscient XOR Not Omniscient (He must be one or the other).

There are two states for free will. Free will exists XOR Free will does not exists (It must be one or the other).

The two states are also exclusive taken together.

There is not a possible state where Free will exists and God is omniscient (God can't know what you will do if you really have free will).

There is not a possible state where free will does not exists and God is not omniscient (in a predictable world with no free will it would be a simple task for God to know everything).

The only possible states are:

If free will exists, God is not omniscient (He can't know what you will do if you truly have free will).

If God is omniscient, free will does not exists (If god knows all possible outcomes then we are automatons).

There is no way around that logic.

I hope that helps clear things up.

Andrew,

ReplyDeleteYou write:

"There is not a possible state where Free will exists and God is omniscient (God can't know what you will do if you really have free will)."

Why not? You seem to be presupposing that God's knowledge of the future states of a system is prediction. But most theists would deny that assumption. Without it, your argument fails.

" ... You seem to be presupposing that God's knowledge of the future states of a system is prediction ... "

ReplyDeleteIt is. "knowledge of the future states of a system" is pretty much the definition of being able to predict the behaviour of that system.

" ... Most theists would deny that assumption ... ".

Maybe, but most theists would be wrong.

" ... Without it, your argument fails ..."

My argument is solid. There are no holes in it. It is logically sound.

If God's knowledge of future states doesn't allow him to make predictions then he is not omniscient.

Tim.

ReplyDeleteYou seem to be suggesting there should be a special form of 'omniscience' especially for gods, whereby they can be all knowing without knowing everything.

Andrew,

ReplyDeletePrediction is inference regarding future states of a syatem based on prior and present states of the system. Foreknowledge need not be predictive: it can be direct knowledge, not inference. You don't take account of this possibility; therefore, what you are criticising isn't the position that your opponents actually hold. They don't believe that God's knowledge about what will happen in the future is a guess, even an informed guess.

There is a literature on this issue; you might want to have a look before you make any further comments on it, since it doesn't advance the discussion much if you do not know what your opponents are actually claiming. See the posts higher up in the thread for references.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteI don't understand why you would think that. What have I written that entails or even suggests that God "can be all knowing without knowing everything"?

It's quite simple. If a god can't predict the outcome from a system it doesn't know everything. In fact, since all events can be said to be outcomes from a system, a god which can't predict outcomes is a god which knows nothing.

ReplyDeleteI'm quite happy to be assured that your god isn't omniscient, BTW.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYour reasoning is mistaken. You write:

It's quite simple. If a god can't predict the outcome from a system is doesn't know everything.

This is false. God can foreknow an event without predicting it: that is the very distinction I am making.

In fact, since all events can be said to be outcomes from a system, a god which can't predict outcomes is a god which knows nothing.

But your assumption is false: not all events are "outcomes from a system" in any sense relevant here. Human free choices (in the libertarian sense) are among those: they may be foreknown directly by an omniscient being with certainty, but because they are not the inevitable outcome of prior events, they cannot be predicted (that is, inferred from prior states of affairs) with certainty.

So does your god know the outcome from all systems or not? If not, it isn't omniscient.

ReplyDeleteYou really can't have it both ways even for your god.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYou ask:

So does your god know the outcome from all systems or not?

Yes. He just doesn't acquire that knowledge by looking at the earlier states of the systems and computing the outcome.

If not, it isn't omniscient.

This latter clause does not apply.

" ... Foreknowledge need not be predictive: it can be direct knowledge, not inference. ... "

ReplyDeleteIf it is not predictive, then god is not omniscient.

If it is direct knowledge then there is no free will.

So your god only knows what will happen AFTER it's happened but he's still omniscient.

ReplyDeleteI guess you're using a private definition of 'omniscience'.

Andrew,

ReplyDeleteYou write:

If it is not predictive, then god is not omniscient.

If it is direct knowledge then there is no free will.

Both of these statements seem obviously false to me. Do you have arguments for either of them?

Tim. I think you'll find that the argument for the second of Andrew's atatements is the subject of this blog.

ReplyDeletePersonally, I'd have thought that a god which does not know the outcome from a system is self-evidently not omniscient. The clue is in the phrase 'does not know'.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYou write:

I think you'll find that the argument for the second of Andrew's atatements is the subject of this blog.

Since the soundness of that argument is the central point in dispute between us here, you can hardly expect me to be moved by the consideration that we disagree.

Personally, I'd have thought that a god which does not know the outcome from a system is self-evidently not omniscient. The clue is in the phrase 'does not know'.

But this is a misrepresentation of my position. If you will search carefully through the comments on this thread, you will discover that I have never said that God does not know the future, only that, as I just said in response to Andrew, he knows it directly as opposed to inferring or calculating it.

>Since the soundness of that argument is the central point in dispute between us here, you can hardly expect me to be moved by the consideration that we disagree.<

ReplyDeleteIn that case I'm baffled by your request for Andrew to repeat the entire argument of the blog which you were discussing.

>I have never said that God does not know the future, <

Ah! So your god DOES know your decision before you make it, and it's always known it. In that case you now have to explain how you could make a different decision and your god still be omniscient.

And if you can't, in what sense you could be said to have free will.

Good luck with that.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYou quote me:

Since the soundness of that argument is the central point in dispute between us here, you can hardly expect me to be moved by the consideration that we disagree.

Then you write:

In that case I'm baffled by your request for Andrew to repeat the entire argument of the blog which you were discussing.

But I have not asked him for that: I have asked him whether he has any argument for his two claims. He presented his analysis as a short and easy way of reaching your conclusion. Since I have argued both by examples and by modal logic that your original argument is flawed, I am interested to know whether he has any argument other than the one you presented. If he has to fall back on yours, well, that's settled.

You also write:

Ah! So your god DOES know your decision before you make it, and it's always known it.

I am puzzled by the air of discovery suggested by your capitalization of the word "does." I have been saying this consistently since my first post at 14 November 2010 18:57.

You continue:

In that case you now have to explain how you could make a different decision and your god still be omniscient.

I have explained this multiple times: see above at 15 November 2010 21:15, for example. You have not, so far as I can see, even understood this response; all of your rejoinders seem to be either misrepresentations of things that I have said very clearly or variations on the (re)assertion that your original argument really is cogent. See, for example, your claim on 16 November 2010 18:35 that I had not answered your question (which I had), your claim at 18 November 2010 08:52 that it wasn't fair of me to answer your question and then point out that from my answer you cannot infer what you wish to infer (with the mistaken suggestion that I was claiming my answer wasn't an answer to your original question), your misrepresentation of my position in your note of 18 November 2010 18:45 (complete with the personal insult at the end), your repetition of the misrepresentation at 19 November 2010 09:38 (complete with the insult about a "heap of verbiage"), etc.

I welcome thoughtful interaction with what I have actually said. And I would welcome thoughtful discussion of any of the literature on this subject that I listed in my comment at 27 November 2010 14:43. But neither repeated misrepresentations nor mere foot-stomping will advance the discussion.

This discussion is becoming increasingly Byzantine, even bizarre. I'm wondering whether you're actually following your own argument.

ReplyDeleteAs before, you now appearing to be arguing that your god IS omniscient because it knows everything, but it doesn't know what your decision is until after you've made it, at which point it knows your decision and so becomes omniscient again.

Conveniently, you forget that learning by discovery inevitably means prior ignorance (i.e. not omniscience).

I think it's plain that you know you can't escape the logic of the argument but you've managed to convince yourself that you've found a workaround which enables you to hold two diametrically opposed views simultaneously, either of which can be produced as the need arises, so you don't need to face the inevitable conclusion of the nasty logic, which is:

Either:

Your god is omniscient and you don’t have free will – and the Bible is wrong.

Or

You have free will and your god isn’t omniscient - and the Bible is wrong.

I suspect it’s the inevitable conclusion from either of which is preventing you from admitting the logic.

And, with that, I think my part in this discussion is over.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYou write:

This discussion is becoming increasingly Byzantine, even bizarre. I'm wondering whether you're actually following your own argument.

I would have to return the compliment on that one; it is clear to me that you aren’t following it at all.

As before, you now appearing to be arguing that your god IS omniscient because it knows everything, but it doesn't know what your decision is until after you've made it, at which point it knows your decision and so becomes omniscient again.

I have already dealt with this misunderstanding above. See the note at 15 November 2010 21:15, where I wrote, in part:

You will do X. God knows (and has known) that you will do X. You are free to do Y instead of X. But if you were to do Y, then it would have been the case all along that God knew that you would do Y. No contradiction emerges at any point. [Emphasis added]

If God would have known all along that you were going to do Y, then obviously God isn’t discovering it.

Conveniently, you forget that learning by discovery inevitably means prior ignorance (i.e. not omniscience).

Does it seem appropriate to you to throw around an insult like this when your criticism depends critically on your failure to pay attention to verb tenses in what I have written?

I think it's plain that you know you can't escape the logic of the argument but you've managed to convince yourself that you've found a workaround which enables you to hold two diametrically opposed views simultaneously, either of which can be produced as the need arises, so you don't need to face the inevitable conclusion of the nasty logic, which is:

Either:

Your god is omniscient and you don’t have free will – and the Bible is wrong.

Or

You have free will and your god isn’t omniscient - and the Bible is wrong.

I suspect it’s the inevitable conclusion from either of which is preventing you from admitting the logic.

Rosa, in the absence of any actual fair-minded engagement either with my argument, or with the literature I have cited, this kind of rhetoric is just that -- empty grandstanding. You are free (!) if you like to continue to believe that your argument is a shining piece of logical rigor and that all Christians are simply idiots. But you must not expect people who have actually looked into these issues -- who have studied modal logic, who have read the relevant literature, and who make distinctions you refuse to observe -- to be impressed with your foot-stomping insistence that you are right.

>You will do X. God knows (and has known) that you will do X. You are free to do Y instead of X. But if you were to do Y, then it would have been the case all along that God knew that you would do Y. No contradiction emerges at any point. [Emphasis added]<

ReplyDeleteCan you really not see that what you're saying there is that your god's 'knowledge' changes if you change your decision?

This isn't omniscience; its learning by discovery.

If that simple point is beyond you then words fail me.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYou write:

Can you really not see that what you're saying there is that your god's 'knowledge' changes if you change your decision?

This isn't what I am saying at all. Your inability to distinguish what I am saying from what you have written above is, I think, the central difficulty that you are having in understanding what I am claiming.

In this world -- call it world 0, or w0 for short -- God knows today that you will, in fact do X rather than (incompatible action) Y tomorrow.

For you to be free to do otherwise is, by definition, for there to be some other possible world -- call it w1 -- in which you do, in fact, do Y rather than X.

It does not follow from these two claims that in w1, God (now falsely) believes that you will do X and you trick Him by doing Y. Rather, the standard and well-established position is that in w1, God has all along believed, correctly, that you will do Y.

Breaking it down:

In w0, God knows today that you will choose to do X tomorrow, and you do in fact choose to do X tomorrow.

In w1, God knows today that you will choose to do Y tomorrow, and you do in fact choose to do Y tomorrow.

World w1 is possible relative to w0. (I mean this simply in terms of the relative possibility relation in standard Kripke semantics for possible worlds.) In virtue of this, your action in w0 is free: the existence of a world that is possible relative to w0 in which you do Y rather than X fulfills the definition of libertarian freedom for your choice to do X, namely, that you could have done otherwise. If the relative possibility relation is symmetrical, then the model fulfills the definition both directions: your choice in w1 to do Y is also free. In S5, the most common modal system, the relative possibility relation is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

In neither world is God mistaken about what you do. In both worlds, your choice is free.

That's all.

Sigh. This is becoming more and more bizarre.

ReplyDeleteYour argument now seems to be that when you choose, like Schrodinger's Cat, you and your god discover what alternative reality you are both in, but it is always the one in which your god was right.

And in this way your god can be both surprised by your decision and knew what it would be all along.

I think this discussion just ran over the edge of rationality into some sort of surreal alternative.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteYou write:

Sigh. This is becoming more and more bizarre.

Which part of modal logic did you wish to contest?

Your argument now seems to be ...

Actually, I have been saying the same thing since my first post here. The implication that I have shifted my position is completely unwarranted.

... that when you choose, like Schrodinger's Cat, you and your god discover what alternative reality you are both in,

Rosa, can you give any evidence whatsoever for your characterization of my position as one in which God discovers anything? If you cannot, would you consider actually reading what I have written carefully enough to avoid these crude and bizarre mischaracterizations?

... but it is always the one in which your god was right.

Yes, God is always right. That much you actually have properly understood.

And in this way your god can be both surprised by your decision ...

Nope. God is never surprised. I have no idea why you would think this follows from anything that I have said.

I think this discussion just ran over the edge of rationality into some sort of surreal alternative.

You're welcome to provide some supporting argumentation and evidence for your position. But until you do, you are not entitled to have it regarded as established fact.

My brain almost exploded reading this. The lengths people will go to in order to hold on to the idea that an omniscient god and free will can exist simultaneously never cease to amaze me.

ReplyDeleteRosa, I'm totally on board with everything you argued here. I rarely comment on blogs but I had to say something here.

I supose I should thank you for showing the absurd mental gymnastics needed to cope with the cognitive dissonance of holding two diametrically opposed views simultaneously and showing how you need to do that to retain your proud god delusion.

ReplyDeleteAnd that really IS my last word with you on this topic.

Rosa,

ReplyDeleteSaying it won't make it so. I have provided you with arguments; I have provided you with the technical formulations of the arguments using the best available modern formal tools; I have provided you with a bibliography.

And you have ignored it all, brushing it aside with a few snide comments about "verbiage."

You can't even be bothered to read what I have written carefully enough to characterize it correctly. You are providing a disturbingly good case that your reasoning takes the following form:

Tim disagrees with me.

Therefore,

Tim must be wrong.

Therefore,

Tim must be saying something stupid.

Here's something that sounds stupid.

Therefore,

It must be what Tim is saying.

I have lost count of the number of instances in this thread that fit this dismal pattern.

You may believe what you like. But you have made it abundantly evident that you do not know what you are talking about and are not willing to put in even minimal effort to correct that state of affairs.

Tim.

ReplyDeleteThis wil be my and your last comment on this thread since you are clearly unable or unwilling to grasp the simple concept that, no matter how 'clever' you imagine your 'technical formulation' to be, if it fails the simple test of not reaching absurd conclusions, then it is false.

You appear to believe that if you can come up with a 'technical formulation' with which to prove that black is white of indeed any colour you want it to be to serve the needs of your argument at the time, it must be right.

It is clearly absurd to argue that a god can be omniscient yet not know something, and that alone should have told you there was something wrong with your 'technical formulation'. Your test appears to be that it allows you to arrive at the required conclusion.

I'm afraid your requirements do not determine what is logical no matter how important you think you are nor how earnestly you wish it did.

This discussion is now at an end.

Rosa, it seems you are unwilling to consider any counterclaims or arguments, and instead prefer strawmen. It is also clear that you do not understand contemporary philosophy; this is a must in order to have this debate. Modal logic is just the logic of the possible and the necessary, so that to say something is necessarily not possible in the face of a possiblistic formulation is to beg the question. Your dismissal of Tim behind rhetoric masks the lack of philosophical training. I am not trying to be rude, but this may help you in the future.

ReplyDelete@Rosa and @Andrew, with all due respect I think Tim has demonstrated your claims to be unfounded.

ReplyDeleteI think the reason why there is confusion around this issue is because of over-anthropomorphitic thinking whereby God is supposedly bound by the space-time dimension that we are experiencing.

Omniscience (acquaintance with ALL facts) or any kind of knowledge (acquaintance with some facts) of events and the free will required to carry out those events are completely separate.

Arthur/Randy.

ReplyDeleteSorry but I don't think there is any escaping the conclusion that a logical contruction which leads to a patently absurd conclusion is itself absurd, no matter how clever or elegant it's construction may have been.

If you can conclude that a god can be omniscient yet not know everything then your logic... well... isn't, no matter how fervently you wish it was and even if its failure strikes at the heart of a much-cherished superstition.

BTW, Arthur, I note your attempt to invoke the 'special needs' clause to exempt your god from normal logic. You may like to read my blog "The Special Needs God of Creationism".

Hi Rosa.

ReplyDeleteI believe Tim has provided lucidly sound arguments (both in technical and in layman’s terms) for the compatibility between Omniscience and Freewill. Based on your characterizations of Tim’s arguments it does not appear that you’ve fully understood them. In the interest of advancing the dialog I’m offering to walk you any line of Tim’s argument dated “19 November 2010 01:06”, that may not have been clear to you. In that vein, do you mind paraphrasing what you believe he said in that post?

josephtime.

ReplyDeleteYes I'd be delighted to hear a cogent explanation of how a god can be omniscient whilst not knowing everything, preferably without me being required to hold two mutually exclusive views simultaneously.

FYI, your scientific facts are wrong as to whom uses the bible. The entire bible is used by Christians. Jews are still waiting for their messiah- so the new testament of the bible is irrelevant. The Muslims utilize the koran.

ReplyDeletePeter. I expect you avoided the main point for a good reason....

ReplyDeleteIf you had read the blog you would have seen I talk about the god of the Bible, who IS the same god that Jews and Moslems believe in, but perhaps you just didn't know that.

Hint: the clue is in the words I used.

Nice attempt to avoid answering the point though.

Hi Rosa,

ReplyDelete@Rosa:” preferably without me being required to hold two mutually exclusive views simultaneously”

Perhaps you misunderstood. My question was whether you mind paraphrasing what you believe Tim said in his “19 November 2010 01:06" post.

If you believe that post contains a contradiction do you mind quoting the text were you believe that occurred?

The two mutually exclusive things both you and your alter ego Tim require me to believe simultaneously are:

ReplyDelete1. Your god is omniscient, i.e., it knows all things and has always known them.

2. We can decide to do something other that what your god has always know we would do.

If you can get passed that without your usual fudge carefully covered by a heap of verbiage, or complaining that my refusal to do so is unfair and unreasonable, then please do so, as I have yet to see it done.

Hi Rosa, you did not provide the exact set of quotes from Tim’s “19 November 2010 01:06" post which you believe contradict each other. Do you mind providing them?

ReplyDeleteHi Tim, or whatever you're calling yourself today. Were there any words in my last reply to you which gave you particular difficulty?

ReplyDeleteIf not, why not address it?

After all it IS what this blog is all about and which you've been desperately avoiding all along.

Did you hope I hadn't noticed?

Hi again Rosa. I find it remarkable that despite multiple opportunities to do so you have yet to provide the *exact set of quotes* from Tim’s “19 November 2010 01:06" post which you believe contradict each other. What you’ve done instead is state what you *think* Tim said. The twain are not the same :-)

ReplyDeleteHi again Tim.

ReplyDeletePerhaps I misunderstood you and you were saying all along that a god can't be inerrantly omniscient if it doesn't know our decisions before we make them.

And I thought you were disagreeing with me but just finding it difficult to put clearly, so trying to hide your difficulty under a tangle of verbiage.

I'm glad we've cleared that one up. I can understand your annoyance at being thought to hold two mutually exclusive views simultaneously through fear of what an invisible magic man in the sky might do if you were rational.

I am surprised to read this article by Rosa because it's in the strains of an article I wrote on my blog regarding godly love and free choice and the inherent fallacy involved: http://borici.blogspot.com/2011/04/two-fundamental-problems-with.html

ReplyDeleteI don't see why you're surprised since your blog was written yesterday (April 29, 2011) whilst mine was written on November 5, 2010.

ReplyDeleteI am not surprised in the context of when you came up first with it, but rather I'm happy with the fact that few other people, to my knowledge, attack the fundamentals of monotheism, rather than merely attacking existence arguments, such as is the case in almost all public debates...

ReplyDeleteAh! I see. Sorry if I read something into your comment which wasn't intended.

ReplyDeleteOf course, religion can be (and should be) confronted on many levels, wherever if falls short on basic logic.

Hi Rosa,

ReplyDeleteLet’s recap. On “10 April 2011 15:35” I asked whether you could paraphrase what you believed Tim said in his “19 November 2010 01:06 post. You responded in part on “10 April 2011 16:57” asserting that Tim’s arguing required you “to hold two mutually exclusive views simultaneously”. Despite at least three separate requests that you produce any contradictory quotes from Tim’s “19 November 2010 01:06" post you have not done so.

It seems then that you have not provided the evidence required in order to demonstrably conclude that Tim’s “19 November 2010 01:06" post contains a contradiction.

@Rosa:” Perhaps I misunderstood”

It seems so. Erring on the side of explicitness… It seems that your assumption, that Tim’s “19 November 2010 01:06" post contains a contradiction, is based on your misunderstanding of what he wrote.

@Rosa:”a tangle of verbiage”

Do you mind sharing which quotes you found difficult to understand? Like I said on “10 April 2011 15:35” I’m offering to walk you through any line of Tim’s argument.

Cheers!

Great question, may I suggest perhaps that Foreknowledge does not imply Predestination. I maybe wrong but here’s how I got there.

ReplyDeleteLet me posit a potential scenario: You and I go to the horse races. We’ve been following our favorite horse for years. His name is Lucky. He’s been trained by the best. He reserves his energy till that last lap and then he turns on the juice. We bet on him to win. The race starts, but as the horses go into the last lap Lucky decides to be obstinate and refuses to put in extra effort and loses the race by 10 yards to a horse named Gimp.

We are bummed and head out of the stands. Suddenly a gray haired man shows up. He claims to be Dr. Emmett Brown. He assures us that he can take us 20 mins into the past. We hop into his DeLorean and we go back 20 mins. It’s the beginning of the race. Avoiding our former selves, we go to the window to make a new bet.

Questions:

1. Who should you bet on? (I’d say Gimp).

2. Does Lucky have the freewill to do what his wants this race and put in that extra effort? (I’d say yes).

3. Does your foreknowledge of Lucky’s choice force Lucky to do it again? (I’d say ‘No, your foreknowledge will not affect Lucky in anyway! Just because you know what Lucky is going to do does not mean you MADE Lucky do that. Lucky remains an independent freewill agent. Lucky remains responsible for his own choices.’

In other words Lucky is not influenced by your knowledge of what he is going to do. Foreknowledge does not imply predestination.

In this example as in the question, we presume that we are not postulating that there will be quantum universes caused by our rip in the time fabric when we returned thru the Time Machine wormhole. The time travel example is merely to provide an idea of a possible scenario. The real scenario maybe different.

E.g. At the point of the Big Bang there was no time or space. Thus whatever created the Big Bang (we are postulating it’s God) must exist causally (that’s cause-all not casually) prior to time and space. Thus, whatever created the Big Bang must be extra dimensional. Perhaps this thing views time the same way as we view a square all at once. This “thing” could then possibly be omnipresent in time and space. Thus the creator’s foreknowledge need not be one that predestines anyone. Note that does not mean that a creator that predestines people is not also possible, just not required.

So in summary Lucky had freewill, Lucky has freewill and Lucky will have freewill. I could be wrong but it seems that foreknowledge does not necessarily imply predestination.

Are you suggesting a god would discover instances of it's own errancy then go back in time and rig things so it just LOOKS inerrantly omniscient? An errant god who's just too vain to admit to it?

ReplyDeleteHow would such a universe differ from one which had a god who was a mere observer, please?

Tim. As I said, if I've misunderstood your position all along and that you agree a god can't both be omniscient and not inerrantly know our choices in advance, then I'm happy to accept your correction.

ReplyDeleteHowever, if you require me to believe that a god CAN be inerrantly omniscient and not know something simultaneously then I'm afraid I can't be that intellectually dishonest. Continually whining about me not being dishonest enough to agree with you won't change that, I'm afraid.

No amount of verbiage or smoke-screens asking me to provide a non-existent quote to divert attention from your difficulty is going to change that, no matter what you call yourself.

I’m not sure why errancy comes up. Could you elaborate?

ReplyDeleteAs to the deism question. OK let me think. In the example, I previously dreamed up, you did not participate in the events. Yet thinking about it, it seems that it follows logically that if you had that power you could tweak events or even participate in certain events to ensure that certain of your plans/prophecies come to pass, all without interfering in the natural consequences of the free agent’s freewill choices. For instance, in the example, let’s assume you went back 4 years and ensured that Gimp was sent to the trainer who would be the one who was able to ensure that Gimp could feasibly win against Lucky. Thus ensuring that Lucky would actually have to exercise his perseverance to win.

Now I have to admit in my example I did not use moral freewill, more of a motivational freewill. Yet most of the above discussions have been about moral freewill, not about what shirt one chose to wear. It’s more of an issue if one person chooses to hurt someone else. So it’s possible that you as a time traveller could go back in time and set up opportunities to make moral decisions even if you removed some of their opportunities to pick certain non-moral decisions. E.g. In the example above you removed Lucky’s option to NOT have to race against Gimp. In fact you could even keep going back and changing the trainer till you found the one that was able to give Gimp a fighting chance.

Again I’m just opining here. I could certainly have missed something.

In fact, if one knows all contingencies one can plan accordingly without ever actually having to "tweak". It's sort of like building a network router, one knows the worst case way that each of the inputs ports can act and if you are good enough you can design a router that does what you want it the first time.

ReplyDeleteHello again Rosa.

ReplyDeleteRosa:”asking me to provide a non-existent quote”

That is an admission that Tim’s “19 November 2010 01:06" does not contain a contradiction. The reason I’m coming to that conclusion is that on “10 April 2011 15:35” I asked whether you could paraphrase what you believed Tim said in his “19 November 2010 01:06 post. You responded in part on “10 April 2011 16:57” asserting that Tim’s arguing required you “to hold two mutually exclusive views simultaneously”. Despite at least four separate requests that you produce any contradictory quotes from Tim’s “19 November 2010 01:06" post you have not done so.

Rosa,