And another quote from Carl Sagan, referring to the famous photo of Earth seen as a tiny pale blue dot from beyond Pluto, because one is never enough:How is it that hardly any major religion has looked at science and concluded, "This is better than we thought! The Universe is much bigger than our prophets said, grander, more subtle, more elegant?” Instead they say, “No, no, no! My god is a little god, and I want him to stay that way.” A religion, old or new, that stressed the magnificence of the Universe as revealed by modern science might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and awe hardly tapped by the conventional faiths.

Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

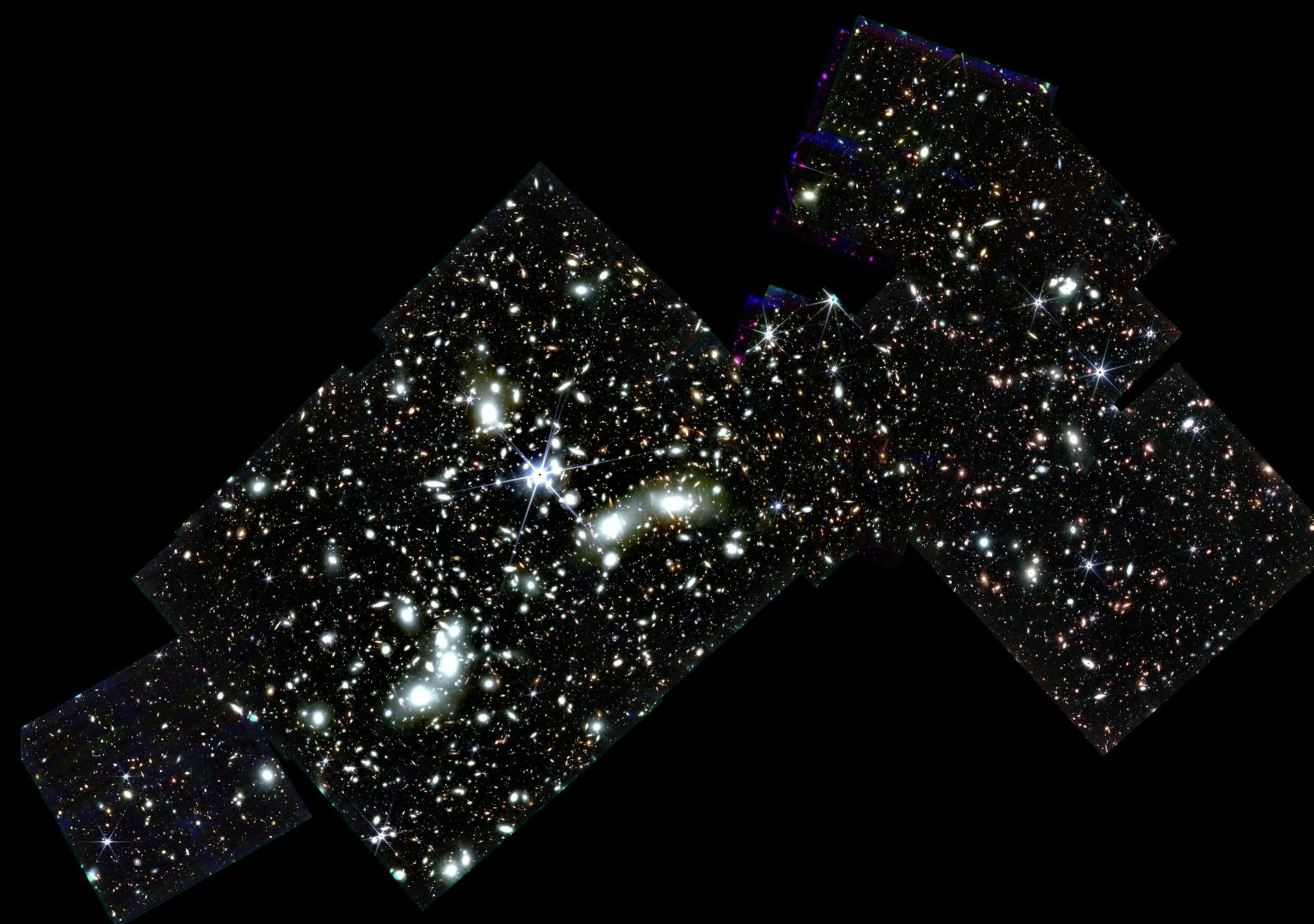

What would Carl Sagan have made of the images now coming from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)? The final one in the following article is of a segment of sky a fraction the size of a full moon. Tens of thousands of points of light in it each represent a single galaxy. Each of those will contain upwards of half a trillion stars, around each of which there is a good chance of a planetary system and possibly an Earth-like planet orbiting.Ann Druyan suggests an experiment: Look back again at the pale blue dot of the preceding chapter. Take a good long look at it. Stare at the dot for any length of time and then try to convince yourself that God created the whole Universe for one of the 10 million or so species of life that inhabit that speck of dust. Now take it a step further: Imagine that everything was made just for a single shade of that species, or gender, or ethnic or religious subdivision. If this doesn’t strike you as unlikely, pick another dot. Imagine it to be inhabited by a different form of intelligent life. They, too, cherish the notion of a God who has created everything for their benefit. How seriously do you take their claim?

Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space.

Are we so arrogant as to assume this was all made just for us and that a mind-reading creator god scrutinises this one small pixel, watching to see if anyone touches their genitalia, loves the wrong person, works on a Sunday, gets pleasure from sex or has the temerity to question what the priests tell us and to think for ourselves?

The article is by Colin Jacobs, Postdoctoral Researcher in Astrophysics, and Karl Glazebrook, ARC Laureate Fellow & Distinguished Professor, Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, both of Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia, lookt at how the JWST images have blown us away over the past year, revealing a Universe never before seen in this stunning detail. It is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be seen here.

10 times this year the Webb telescope blew us away with new images of our stunning universe

It is no exaggeration to say the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) represents a new era for modern astronomy.

Launched on December 25 last year and fully operational since July, the telescope offers glimpses of the universe that were inaccessible to us before. Like the Hubble Space Telescope, the JWST is in space, so it can take pictures with stunning detail free from the distortions of Earth’s atmosphere.

However, while Hubble is in orbit around Earth at an altitude of 540km, the JWST is 1.5 million kilometres distant, far beyond the Moon. From this position, away from the interference of our planet’s reflected heat, it can collect light from across the universe far into the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

This ability, when combined with the JWST’s larger mirror, state-of-the-art detectors, and many other technological advances, allows astronomers to look back to the universe’s earliest epochs.

As the universe expands, it stretches the wavelength of light travelling towards us, making more distant objects appear redder. At great enough distances, the light from a galaxy is shifted entirely out of the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum to the infrared. The JWST is able to probe such sources of light right back to the earliest times, nearly 14 billion years ago.

The Hubble telescope continues to be a great scientific instrument and can see at optical wavelengths where the JWST cannot. But the Webb telescope can see much further into the infrared with greater sensitivity and sharpness.

Let’s have a look at ten images that have demonstrated the staggering power of this new window to the universe.

1. Mirror alignment complete

One of the biggest tasks was getting the 18 hexagonal mirror segments unfolded and aligned to within a fraction of a wavelength of light. In March, NASA released the first image (centred on a star) from the fully aligned mirror. Although it was just a calibration image, astronomers immediately compared it to existing images of that patch of sky – with considerable excitement.

2. Spitzer vs MIRI

On the left is an image from the Spitzer telescope, a space-based infrared observatory with an 85cm mirror; the right, the same field from JWST’s mid-infrared MIRI camera and 6.5m mirror. The resolution and ability to detect much fainter sources is on show here, with hundreds of galaxies visible that were lost in the noise of the Spitzer image. This is what a bigger mirror situated out in the deepest, coldest dark can do.

3. The first galaxy cluster image

The field is crowded with galaxies of all shapes and colours. The combined mass of this enormous galaxy cluster, over 4 billion light years away, bends space in such a way that light from distant sources in the background is stretched and magnified, an effect known as gravitational lensing.

These distorted background galaxies can be clearly seen as lines and arcs throughout this image. The field is already spectacular in Hubble images (left), but the JWST near-infrared image (right) reveals a wealth of extra detail, including hundreds of distant galaxies too faint or too red to be detected by its predecessor.

4. Stephan’s Quintet

On the left we see the Hubble view, and the right the JWST mid-infrared view. The inset shows the power of the new telescope, with a zoom in on a small background galaxy. In the Hubble image we see some bright star-forming regions, but only with the JWST does the full structure of this and surrounding galaxies reveal itself.

5. The Pillars of Creation

It depicts a star-forming region in the Eagle Nebula, where interstellar gas and dust provide the backdrop to a stellar nursery teeming with new stars. The image on the right, taken with the JWST’s near-infrared camera (NIRCam), demonstrates a further advantage of infrared astronomy: the ability to peer through the shroud of dust and see what lies within and behind.

6. The ‘Hourglass’ Protostar

Only visible in the infrared, an “accretion disk” of material falling in (the black band in the centre) will eventually enable the protostar to gather enough mass to start fusing hydrogen, and a new star will be born.

In the meantime, light from the still-forming star illuminates the gas above and below the disk, making the hourglass shape. Our previous view of this came from Spitzer; the amount of detail is once again an enormous leap ahead.

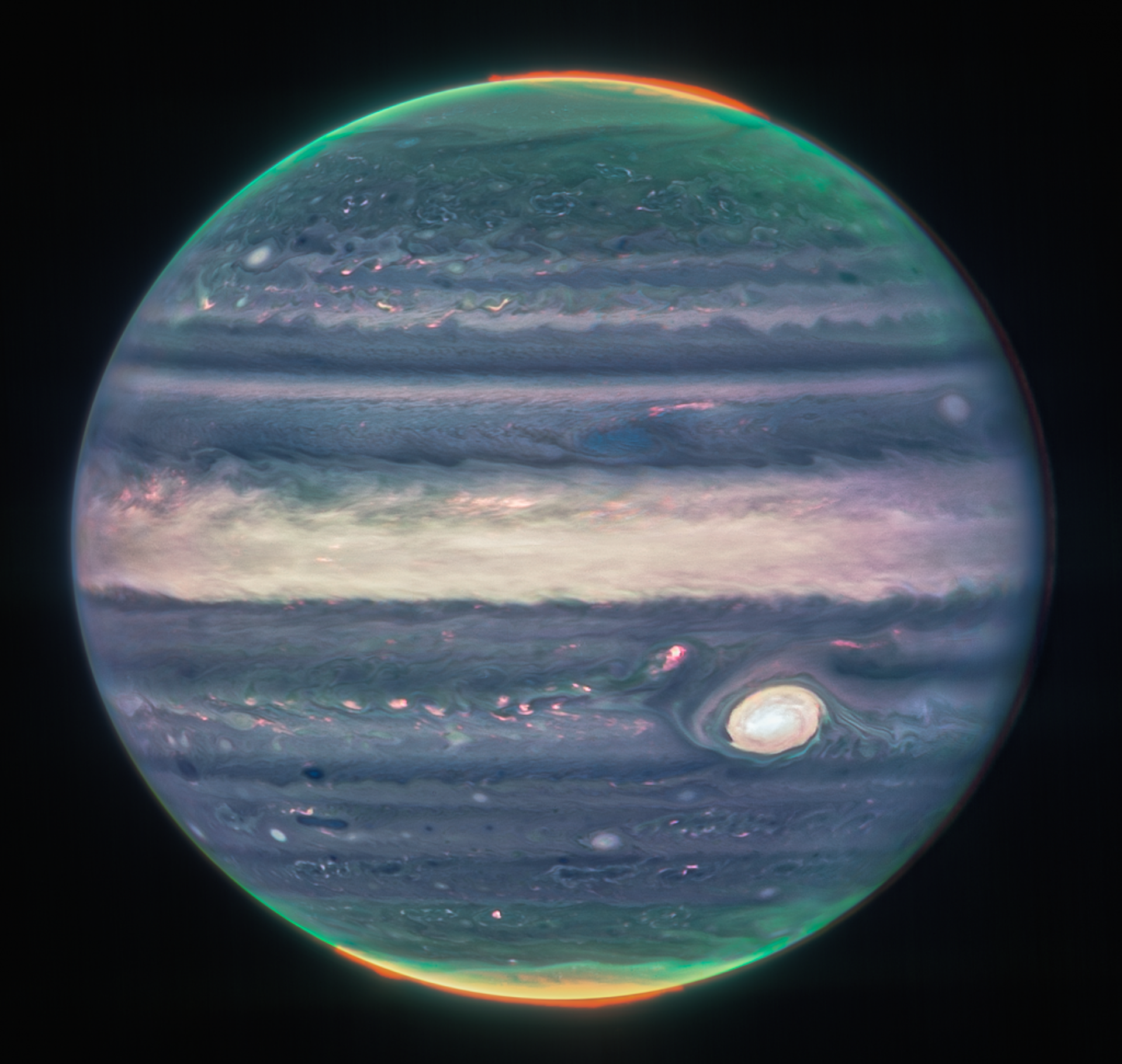

7. Jupiter in infrared

Although JWST cannot look at Earth or the inner Solar System planets – as it must always face away from the Sun – it can look outward at the more distant parts of our Solar System. This near-infrared image of Jupiter is a beautiful example, as we gaze deep into the structure of the gas giant’s clouds and storms. The glow of auroras at both the northern and southern poles is haunting.

This image was extremely difficult to achieve due to the fast motion of Jupiter across the sky relative to the stars and because of its fast rotation. The success proved the Webb telescope’s ability to track difficult astronomical targets extremely well.

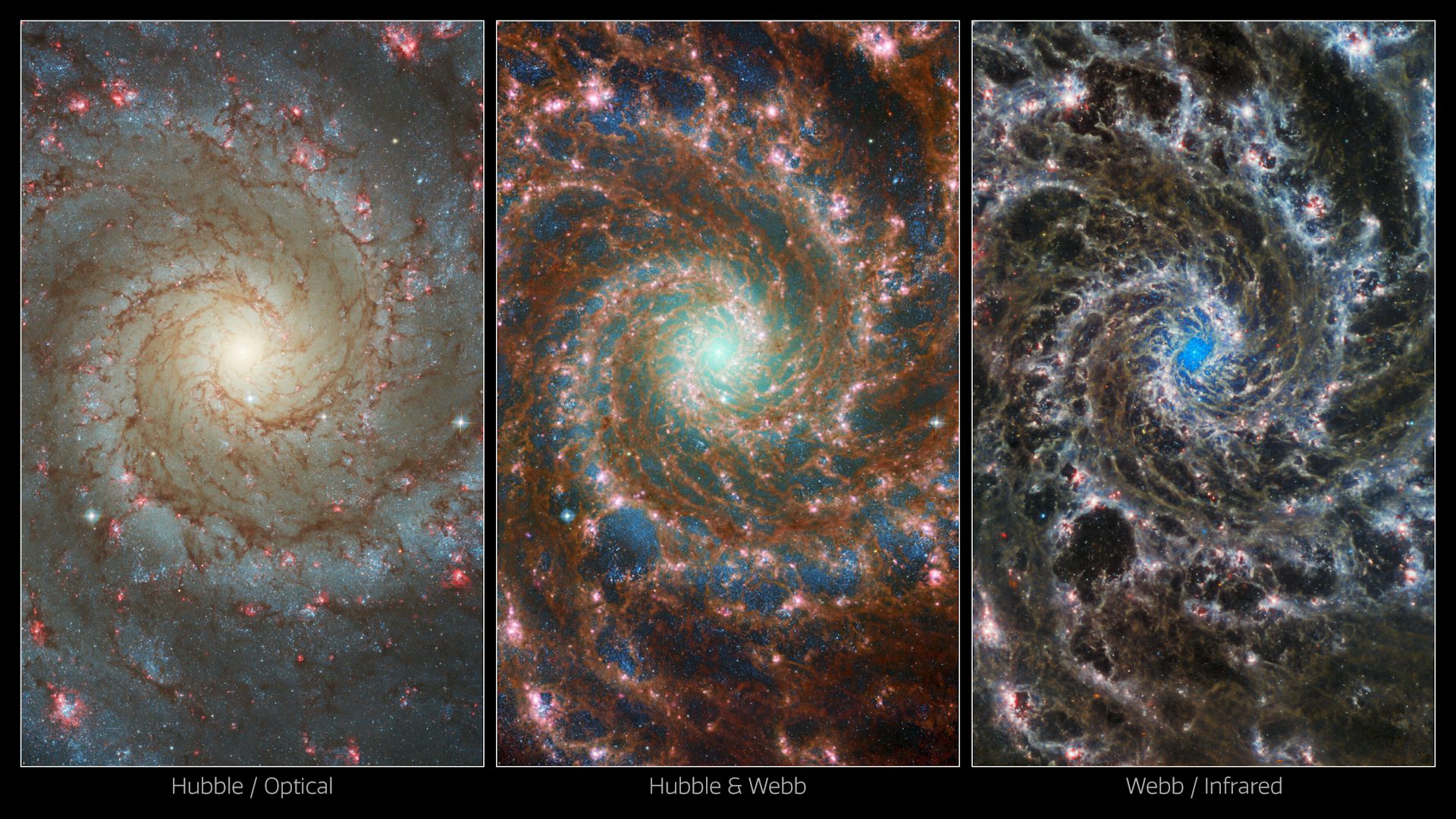

8. The Phantom Galaxy

Much JWST science is designed to be combined with Hubble’s optical views and other imaging to leverage this principle.

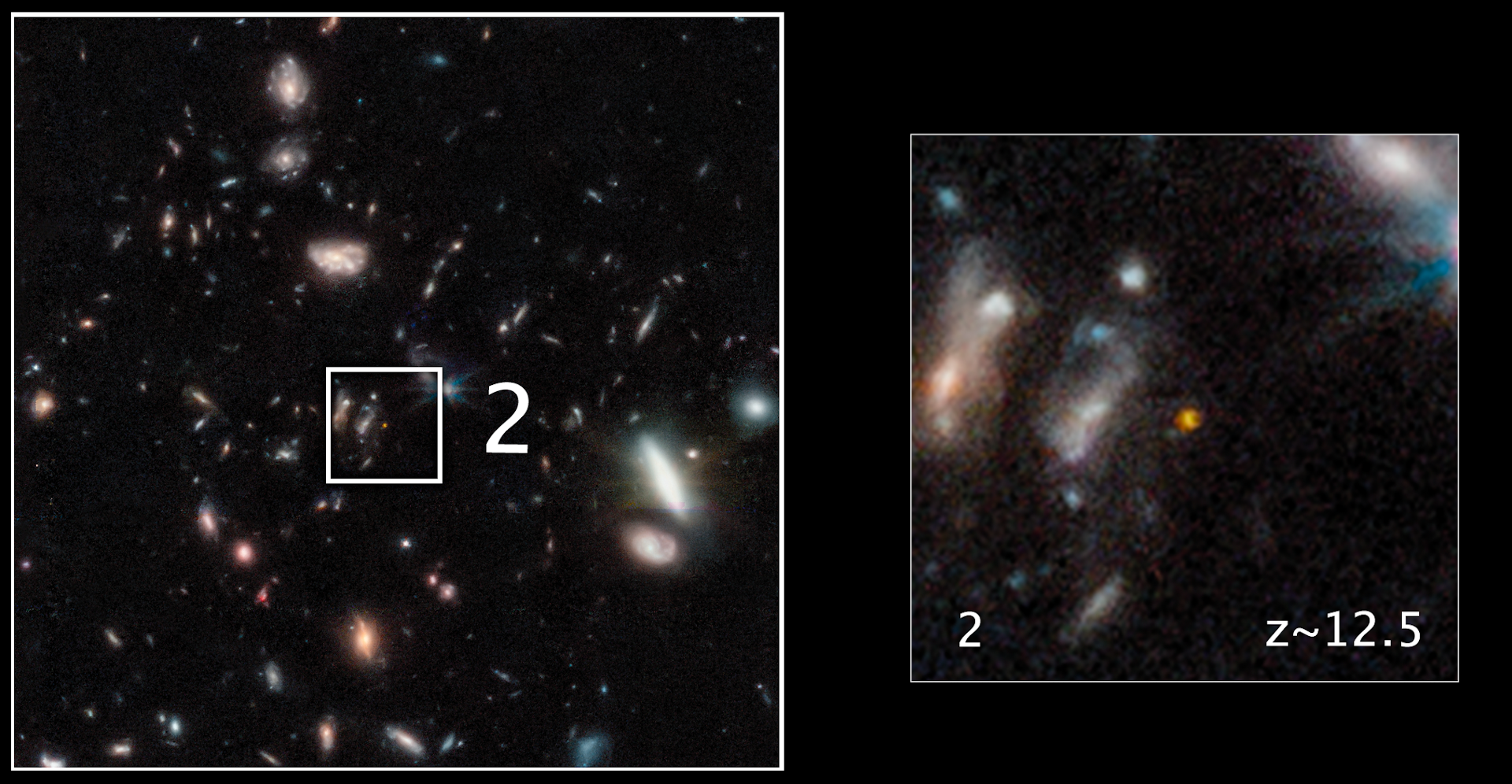

9. A super-distant galaxy

This snapshot is from when the universe was a mere 350 million years old, making this among the very first galaxies ever to have formed. Understanding the details of how such galaxies grow and merge to create galaxies like our own Milky Way 13 billion years later is a key question, and one with many remaining mysteries, making discoveries like this highly sought after.

It is also a view only the JWST can achieve. Astronomers did not know quite what to expect; an image of this galaxy taken with Hubble would appear blank, as the light of the galaxy is stretched far into the infrared by the expansion of the universe.

10. This giant mosaic of Abell 2744

In a patch of dark sky no larger than a fraction of the full Moon there are umpteen thousands of galaxies, really bringing home the sheer scale of the universe we inhabit. Professional and amateur astronomers alike can spend hours scouring this image for oddities and mysteries.

Over the coming years, JWST’s ability to look so deep and far back into the universe will allow us to answer many questions about how we came to be. Just as exciting are the discoveries and questions we can not yet foresee. When you peel back the veil of time as only this new telescope can, these unknown unknowns are certain to be fascinating.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.