As a background to the current industrial disputes in the UK NHS with nurses and ambulance staff striking or planning to strike in the next few days, this is a potted history of the Ambulance service, and particularly my role in it during in the 35 years from 1975 to 2010 when I finally retired.

On Easter Sunday, April 3, 1988, about an hour past what should have been the end of a 12 hour might shift, I was advising a young police constable about what he needed to do to secure the crime scene where a mother had, for no obvious reason, decided to strangle her 5 year-old son with his dressing gown cord, stab her 7 year-old daughter 21 times in the chest with a kitchen knife, stab herself, try to cut her own throat, then run half a mile across a field and drown herself in a nearby pond.

About 30 years ago, five days before Christmas on the last day of the school term, I found myself under a school bus with its back wheel parked on the chest of a 12 year-old boy. Under the bus with me were his mother and father who lived just along the road. What would you say to them? We waited together for the half hour it took for the local fire brigade to arrive and jack the bus up enough to pull the body from under the wheel.

In 1989, on a cold and frosty winter morning, I found myself in the back seat of a car which had gone under the front of a lorry, crushing both the driver’s legs and trapping them under the dashboard, pushed down by the weight of the lorry. The driver, a young woman of about 20 was on her way to start a new Job in Aylesbury. She was not familiar with the country road and lost control on a bend. Both vehicles were on the grass verge. To get to them, the fire brigade needed to remove a section of the hedge with a chainsaw. No-one thought to warn me and my patient of the noise that was about to start not three feet from us.

I had her on a drip and had set up a heart/pulse monitor and fitted a blood pressure cuff so I could monitor her condition. Trying to keep us both warm I had wrapped her and myself in blankets. It took the fire service about three quarters of an hour to pull the car out from under the lorry and remove the roof. My patient survived the ordeal and the orthopaedic team managed to save her legs..

These, and a thousand other similar jobs are dealth with every day by the crews of the UK Ambulance Services and most of the patients from them end up in the NHS being cared for by nurses and doctors backed up by an army of ancilliary staff, cleaners, porters, radiographers, physiotherapists, laboratory technicians, etc. All of these are now bearing the brunts of 12 years of Tory underfunding, continuous reorganization, unfilled vacancies and economic mismanagement and, for the last three years, a raging, life-threatening pandemic for which innadequate personal protection equipment was provided by chums of ministers handed tens of millions of our money to supply PPE that never materialised or, if it did, was unuseable, even being salvaged from the clinical waste of Turkish hospitals.

"Oh! Don't worry! You can keep the money anyway. Thanks for trying!"

In the seventeen years I spent as an operational ambulance paramedic and station manager, these were just a few of the many tragedies we attended as well as the more rewarding calls, such as delivering twin babies on a bathroom floor, delivering a 35-week prem baby in breach on the back seat of a car.

Whatever we went to, we would try to deliver the highest standard of care and compassion, because that was what were there for.

In those days too, the Ambulance Service was multi-purpose, providing both and emergency medical transport service and routine transport for non-emergency outpatient and day-patient. An emergency crews could find a list of outpatients and their day's work planned for them, fitting in the odd emergency when they were clear. When this became untenable as the demand increased, the service was split into a emergency service and a patient transport service, with different control and management structures financed by different income streams. Only then could the Paramedic profession begin to develop into a full emergency care service.

By that time, I was managing an increasingly busy Emergency Operations Centre plus occasionally filling in for the Patient Transport planning officer and day control manager as the need arose. I also began writing software to plan and produce performance reports, having taught myself the programming languages our computer systems ran on. At one point, the software house who supplied our system asked for me to be seconded to them for a period to develop me as a programmer and to develop an automated planning module, but they could not agree a suitable fee with my service, which would have covered my wages, travel and accommodation in Manchester and the cost of covering my shifts.

Since those days, the paramedic profession has undergone profound change - a change we could only dream of in those days 0 as has the technology needed to run and manage a large Ambulance Emergency Operations Center, with satellite tracking, mobile phones and electronic patient records. Now, a front-line ambulance and crew really are a hi-tec extension of the A&E Department, we always tried to be, if only we had had the equipment and training.

In the early days, on my small, rural Ambulance station in Southeast Oxfordshire, a busy night was two calls in a 12 hour shift, three calls was unusual and four calls, unprecedented. Going a full set of 7 nights without a call was common, as was a clear weekend. In my first year in the Ambulance Service in 1976, I worked continuously from Good Friday at 6 pm to Easter Monday at 8 am and never turned a wheel. On one occasion, I was seconded to the emergency Control Room to cover a night shift due to an acute staff shortage. We dealt with three emergency calls for the whole of Oxfordshire and drank copious cups of tea to stay awake.

In 1989, we went into an industrial dispute with the then Tory government which was to last 15 months and got massive support from the public. I led my station through that dispute during which we kept our promise to the public to always have an emergency ambulance available. Such was the support from the public that, from donations given during an hour standing in the local high street with a bucket two or three times a week, we could get enough money to support our colleagues who were not being paid, not being on an emergency shift.

This dispute elevated Tory ministers such as Health Secretary Kenneth Clarke to the level of most hated politician, and the Tories under Margaret Thatcher fell behind Labour in the opinion polls for the first time since the Falklands War. The resolution to the dispute included recognising the paramedic qualification as worth paying for - almost unbelievably now, until then, Paramedic training over and above the basic training of an ambulance man/woman was voluntary and unpaid, and far from universal across all ambulance services.

And then we had the Care in the Community Act, which split the comprehensive health and social care system into the NHS and social care, putting the latter into the hands of under-funded local government - a formula that was almost designed to fail. Simultaneously, the Tory government under Thatcher discovered the liberal notion that mental asylums were repressive, resulting in a massive sell-off of mental hospitals to Tory-supporting property development firms like Barratts and a discharge of institutionalised patients onto the streets, and the Ambulance Service picked up the casualties. Soon, sheltered accommodation for the elderly was privatised and the main aim became profit rather than standard of care and quality of life, and again the Ambulance Service picked up the casualties.

Since then, the NHS has had repeatedly been reorganised - a strategy which seems designed to keep it inefficient and disorganized as, no sooner had a new structure, new lines of accountability and new sources of finance been put in place than the rules were changed yet again. The Ambulance Service underwent the last reorganization with a major merger into large regional services. My Oxfordshire service merged with Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, and Hampshire to form South Central Ambulance Service and new performance targets meant call-prioritization, first response cars and intensive deployment/resource planning. Weekly performance review meetings were necessary to keep performance up to the required standards. My role was to prepare and present a weekly presentation for these review meetings consisting of Statistical Process Control charts on key performance issues for the Northern Division (Berkshire, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire).

During that period of change I moved from operations into Emergency Operations Room management, and then into information management and eventually, following formal retirement, I was invited back to work as a deployment Planning Consultant, responsible for devising and reviewing deployment plans. It was becoming increasingly obvious that as demand increased and finances were squeezed, performance was falling and crews were being stretched to beyond breaking point. The only realistic solution was to employ more staff and put more resources into operation.

That breaking point has now been reached, following years of austerity following the banking collapse, and an incoming Tory/Lib Dem government under David Cameron who gleefully seized upon the excuse to cut funding to all public services, including the NHS and social care, which has always been anathema to the Tories who detest public ownership and the fact that it is depriving them of the chance to make a fast buck out of the misfortune of others.

At the end of that period of underfunding and political hostility, we had Brexit, which means the supply of staff from the EU dried up, and many staff returned home, feeling unwanted and unwelcome, and then the COVID pandemic which piled another layer of demand onto the Ambulance service - the one part of the NHS that can't say no.

Unlike a hospital which can go on 'divert' and effectively close its doors to new admissions, the Ambulance Service can't say no. There is no other service it can go on divert to! If a hospital A&E closes its doors, it just means longer ambulance, journeys, slower turn-round times and, effectively, less available resource.

Now, according to my son who followed me into the profession, an ambulance crew is lucky to get a meal break, or to finish on time at the end of their shift. Calls are continuous and the Emergency Operations Centre has a 'stack' of calls waiting for an ambulance crew to call clear. The question a crew asks themselves when they call clear, is not whether they will get another call, but where it will be, what will they be going to and for how long has the call been stacked? One problem is, that a large proportion of ambulances will be parked outside A&E departments waiting for a trolly or a cubicle to hand the patient over., while A&E staff try to find a bed to admit a patient into so they can take the next patient from the queue outside. Waits of several hours are commonplace.

The Ambulance Service has become the last line of defence in a failing system. A lack of social care means more ambulance calls. It also means more patients who could be discharged to social care if only there were somewhere to discharge them to, so-called bed-blockers, stuck in hospital beds which could be occupied by the patients in A&E who are preventing the ambulance patients being admitted.

Those ambulance crews who can't say no; who have to respond to any call; who work 12 hour shifts without a break and need to work overtime to make ends meet, are due to go on strike for the first time since 1989, because, having coped with COVID and been applauded once a week from our doorsteps, they are being asked to accept an effective pay cut as a thank you. The Tory government, which sees compassion as a weakness in others to be exploited has again picked what it sees as a soft target for who is going to pay the price for their 12-year mismanagement and failure to plan, and doctrinaire adherence to the notion that market forces, and making the rich richer will solve all problems, just so long as the public sector workers are there to pick up the bill with another reduction in their standard of living and cuts in the social wage, as they did following the banking crisis.

After 12 years of neglect and underfunding by a Tory government that is fundamentally hostile to the idea of socialised heath care, the NHS is on its knees. Brexit has deprived it of staff from Eastern Europe, and low pay, low morale and compassion fatigue have seen people leave the Ambulance Service, and the nursing profession in droves, and COVID was the final straw. The Tories repeatedly claim to have provided tens of thousands of new nurses; in reality, all they have provided is tens of thousands of new nursing vacancies.

Nurses have just held a widespread strike for the first time in their history, only to be met with a Tory government slavering at the mouth at the prospect of another battle with 'militant' trades unionists, hoping to repeat Margaret Thatcher's triumph over 'militant' trades unionism, as a detraction from the economic mess their 12 years in power, and in particular Liz Truss' disastrous 44-day experiment with doctrinaire 'trickle-down' economics, as a naked bribe to the party of greed and selfishness that elected her, has left us in.

In the following article, reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence, Kate Kirk, Lecturer in Organisational Behaviour in Healthcare, University of Leicester, with contributions by Professor Laurie Cohen, professor of Work and Organisation, University of Nottingham, explain the background to the nurses' dispute. The article has been reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here:

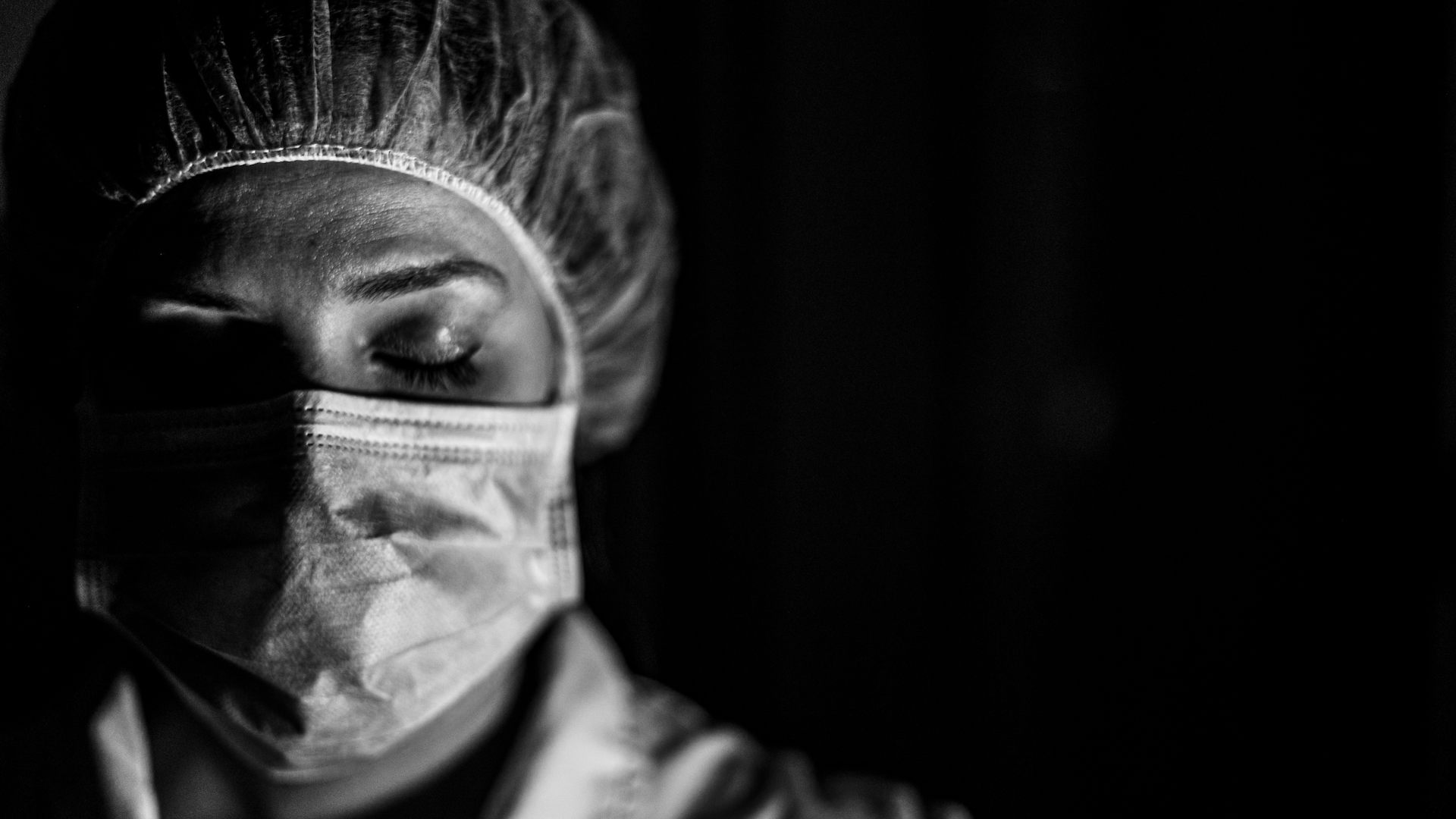

‘It’s like being in a warzone’ – A&E nurses open up about the emotional cost of working on the NHS frontline

Kate Kirk, University of Leicester

As nurses prepare to strike for the first time, an A&E nurse and lecturer in Organisational Behaviour in Healthcare writes about the stress, fear, grief and guilt they feel every day working on the frontline of an NHS in crises.

This was how one nurse in her 40s described an Accident and Emergency (A&E) department to me, and it sounded all too familiar.I noticed how I used the phrase ‘warzone’ quite a few times, when you’ve got trolleys everywhere … full of patients and you don’t know where to turn next. What to do for whom next, and I have said it’s like being in a warzone because you can imagine it. That’s what it would be like in a field hospital … what do I do next? You know it’s dangerous but you’ve just got to do the best you can do. And I’ve heard other people use that term as well. Just how it makes you feel but something kicks in and you just get on with it.

The resuscitation area in the emergency department is a hive of time-critical activity as staff weave around one another at pace. The sheer din is intense: a symphony of alarms, voices and crying out – all varying in pitch and volume, competing with one another. The bays are awash with wires, pipes, medical equipment and pumps to give various medication.

This is the norm. But some nights will always stand out above the others. Once, while I was on shift, a three-year-old girl in a nearby resuscitation bay was receiving treatment for meningitis. Following a substantial and sustained attempt at resuscitation by the paediatric team, she died.

I wasn’t caring for her directly, but it was apparent from the noise how the treatment was progressing and when, ultimately, it was unsuccessful. The screams and cries of grief from the girl’s parents were heard above all other noise when staff broke the news to them that their child was dead. It was unforgettable.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

Many of the adult patients were too unwell to know what was going on. So, despite the communal awareness among staff of the enormous distress close by, we carried on caring for our other patients, offering them the “reassuring face” and warmth they expected. I stood behind one of the curtains for a few moments and swallowed hard at the sounds of the suffering. And that was it. Sadness and distress at the death of a child had to be suppressed for the sake of the other patients.

On the drive home I reflected on the emotional complexity it requires to be a nurse. The need to hide sorrow while juggling great workloads, the pressure of organisational targets and other patients’ seemingly less critical needs requires intense effort and emotional control. That effort is exhausting and draining.

This tragic incident was just one of many similar experiences I have encountered over my 11-year career as an A&E nurse. Heartbreaking and emotionally complex stories like this happen every day in A&Es up and down the country. Nurses have to conceal myriad feelings as standard just to get through their shifts. This includes harrowing, disturbing and traumatic emotion as described in the story above, but also fear and anxiety when they feel overwhelmed and have to deal with aggressive situations. Nurses experience joy and relief when a patient recovers against the odds but frequent guilt and shame at being unable to deliver the standard of care they desire.

The exploration of emotional labour in emergency care has underpinned my subsequent research career. It has motivated me to explore and support this under-recognised area of nursing practice.

“Emotional labour” is a theory coined by sociologist Arlie Hochschild who defines it as “the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display”. When that toddler died of meningitis, myself and the other nurses did our own emotional labour by suppressing our true emotions to ensure the other patients in our care felt reassured. In other words, we remained “professional”.

But the nurses I spoke to are not only dealing with emotions related to grief and bereavement. Because of the crisis facing the NHS, many feel they can’t do their job properly and so have overwhelming feelings of guilt too. A male nurse in his 30s told me:

You can’t be the sort of nurse you might want to be … You can’t nurse people properly in the ED (emergency department) … You don’t have the staff or facilities to do that and it’s just getting worse … I think it’s one of the major things that make it a hard place to work because you feel that you’re not doing the best for the people you’re looking after … it can actually grind you down. As nurses, you want to care for people. You want to make a difference.

A recent analysis by The Kings Fund showed the extreme pressure the NHS is under. More patients than ever are experiencing delays in cancer diagnosis and treatment and longer waiting times in “non-urgent care”.

These pressures have an impact on patients, but also affect those tasked with delivering care. Nurses are quitting in record numbers. By 2030-31 half a million extra healthcare staff will be needed to meet the pressures of demand – a 40% increase in existing workforce. Health and social care staff are exhausted and the workforce is depleted. The negative impact of this crisis cannot be underestimated for both staff and patients.

When nurse staffing is short or lacking in the required skills due to issues like high staff turnover and sickness, research shows that patient mortality is higher and patient experience is poor.

Nurses working in short-staffed areas are twice as likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs, to show high burnout levels, and to report low or deteriorating quality of care in their hospitals. This becomes a vicious cycle as these experiences fuel more staff to leave.

Sickness absence rates in the NHS are higher than in the rest of the economy and 47% of staff felt unwell in the last 12 months as a direct result of workplace stress. One study has shown levels of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder similar to those experienced by soldiers in Afghanistan.

A recent evaluation found that poor mental health and wellbeing among medical staff is costing the NHS about £12.1 billion per year.

Accident and Emergency

In England, NHS patient attendance to A&E has followed an upward trajectory over the last 70 years. In 2019-20 there were 25 million attendances, compared to 21.5 million attendances in 2011-12.

‘Stress, absenteeism and turnover remain alarmingly high among nurses and midwives,' says @bailey_suzie, commenting on the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s annual data registration report. Read the full statement here: https://t.co/hPais1tofm pic.twitter.com/z2nBpnXHiM

— The King's Fund (@TheKingsFund) May 20, 2021

Patient attendance has been growing exponentially in the last ten years. This, together with rises in patients who need admitting to hospital for routine care, fewer hospital beds and staffing pressures has resulted in unsafe patient overcrowding in A&Es. Research has shown how overcrowding increases adverse clinical outcomes including death, medical error and decreased patient satisfaction.

The most recent figures for 2022-23 show the worst A&E performance (waiting longer than four hours) on record.

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, those working in emergency care are more likely than other healthcare workers to experience poor wellbeing, suffer psychological illness and to quit their jobs.

Nurses open up

According to the Royal College of Physicians, NHS staff are the greatest asset of the NHS and are fundamental to delivering high-quality care. Staff go “the extra mile” as standard: they work without breaks, come in on their days off and often stay unpaid, long after shifts have finished.

My PhD aimed to understand the experiences of nursing staff in A&Es and how they managed their emotions to cope with these challenges and still meet patient expectations. This is critical because emotional labour, in particular, is linked to wellbeing and burnout.

I worked with a team of academics to undertake an ethnographic observation study across two large NHS trusts in the UK. This involved 200 hours of observation and 36 in-depth interviews. We spoke to A&E nurses of all seniority and support staff in both organisations. We found that the nursing staff “did” intense emotional labour routinely in their work. As one male nurse in his 30s explained:

The nurses adapted their emotional response to support a vast spectrum of patient need. Among these complex and intense emotions, we heard examples of nurses who felt scared, guilty and endless examples of nurses being short on time and resource, feeling stressed, and grieving over patients who died. They hid their true feelings to make sure their patients felt safe and to build trust – whatever the circumstances. They moved at pace between groups of patients and adapted their appropriate “professional” response.… you know, you see quite a lot of bad things. You deal with a lot of complex things and … you do have to put up a front, a very professional front, and you have to deal with different levels of communication as well. You’ll get someone with mental health problems one minute, get someone with a broken finger the next minute, someone’s collapsed … Then you just have to mould yourself into a different personality … to communicate with [each patient], to get on their level of need … you’ve got to go from zero to hero, as far as I’m concerned … Never knowing somebody to doing something really, really intimate … So you’ve got to get to know them really quickly, for them to be able to trust you

We collected data over a six-month period and found that the nurses used various metaphors to describe experiences of managing their emotion in A&E. We found some key themes.

Guilt and shame

Nurses described to us how sometimes the environment can feel overwhelming, using that “warzone” phrase to explain their experiences. This sense of relentlessness and “combat” has implications for the nurses emotional labour too. Their nursing values (related to providing care and compassion) are conflicted with the realities of contemporary practice. The standards of care possible amid the operational pressures don’t reflect these nursing values (built on warm and reassurance).

The nurses I spoke to weren’t able to deliver the quality of care they wanted to. This means they needed to suppress the associated frustration and guilt. There was a sense of genuine sadness and even shame that they couldn’t give their patients the time or connection they longed to.

This former nurse said one incident in particular “changed her outlook on A&E” and led to her thinking, “I can’t work here anymore”.

Assembly lineIt was a really, really busy winter day … trolleys were stacked … and right in the middle I had a little old lady in her 90s who suddenly deteriorated and I could do nothing but stand in the middle of all the trolleys, in front of all of those people, holding her, shouting for help. I just thought that if that was my grandmother, I’d be disgusted.

Instead of meaningful patient and nurse relationships, the care delivered in A&E often feels transactional and lacking emotional connection. Interactions were quick and task based. Again this results in the nurses feeling dissatisfied and often guilty. Jill Maben, a professor of health services and nursing, found that when nurses are unable to deliver the care they want to, it doesn’t line up with their values. This disconnect (between values and reality) can be a reason why nurses leave the profession.

The clinical realities of the nurses work went against their deep moral values and the desire to care. This was reflected by many of the nurses I met, including a female nurse in her 40s, who said:

For some of the A&E nurses interviewed in the study, the inability to deliver the standard of care they wanted to was unmanageable and they left. One told me she quit because A&E was so busy it meant ignoring some people who were waiting long hours. She said:I’ve actually used that term assembly line – it’s like a production line of patients … you’ve got [ambulance] crews coming in constantly … You take handover from the crew, do the basics, move on to your next patient. Take handover, do the basics, move on to your next patient. You might not even see that patient again … it means there’s a definite lack of care there … I go home feeling very unsatisfied because you’ve not cared for people, you’ve just checked their observations, given them any immediate treatment they need, but the actual caring aspect of it, you’ve not really done any of that.

Stress and fearI think you need to be quite stony-hearted because it’s a hard place to work … I care too much. I can’t walk past somebody that says ‘can you help me?’ and unfortunately you don’t have time. In A&E, you don’t have time to stop for every person who says ‘excuse me’. You need to be able to walk past people …

Sometimes the nurses said they were scared: scared of the overwhelming workload as well as the threats and intimidation they received from patients. One of the nurses, in her early 20s, described how she “put on a front” to her patients. She did this to hide any anxiety around her inability to cope. She was protecting her patients from her true emotion and as a result, making sure they felt safe:

She said it was important not to let patients see that they were “stressed and flustered” because “it gives them reassurance … to show patients that you’re confident and you can get on with it”.I suppose from the outside it could appear that you’re managing well, you’re getting to your patients, you’re putting on a front, you’re smiling, you’re happy. You present yourself. You tell them what the plan is, what’s going to happen, what to expect next. Then you’re whisking off to take the next patient or moving on to another area. So, yeah … patients’ or relatives’ perception could be that it doesn’t look as busy because they don’t see what’s going on behind the scenes. They don’t see what resus [resuscitation] is like, that there’s minus three beds in there … Or the walk-in side … there could be probably five or six people in the waiting room wanting to know why they’ve not been seen straightaway because it doesn’t look busy, whereas resus is just behind the doors and there could be massive traumas going off.

Again the nature of this emotional labour (this time suppressing fear and anxiety) is guided, in part by the need to protect and reassure patients under their care. Another nurse, in his 30s added:

For some, the extraordinary feeling of stress involved is overwhelming but the nurses stay calm and professional outwardly, as described by a female nurse in her 30s:…you’re actually like a parent to everybody. You’re everybody’s mum or dad. So on the surface you do have to look calm and you have to look like you’re in control because they’re vulnerable and you can’t be panicking because it’s just not going to solve anything, whereas underneath you might not have a clue what to do, but you have to come up with something and you might be crapping yourself … it’s just a mask, isn’t it?

She added that the same amount of pressure and noise could amount to “torture” for some people.It’s a mixture of stress. Sometimes you just feel like you just don’t know where to start. Sometimes in the environment where it’s overcrowded like that, you can feel very enclosed and it can feel quite pressurised because … you can feel like everyone is looking at you.

But sometimes the stress was related to fear and anger when dealing with an aggressive and abusive patient. Again the nurses emotion remained hidden and out of sight of the patient and others in the waiting room. One nurse described an incident on a particularly busy night with man who was getting tired of waiting with a minor injury.

She offered him assistance, as he was struggling to walk. But he shouted at her in front of a full waiting room, including children: “Why don’t you just fuck off and die?”

The nurse was shocked. The entire waiting room was staring back at her. She said she couldn’t speak and that her “blood was boiling” but she was also frightened. She couldn’t engage with him so she walked away, afraid she would shout back or cry if she tried to speak. “Had I been outside of work, I wouldn’t let people speak to me like that,” she said.

She added that if those unruly and abusive patients were shown a baby being resuscitated in the next room they might rethink their behaviour and show more respect.

Grief and trauma

But all feelings must be managed, even sadness and grief – perhaps these emotions above all.

This female nurse said that managing emotions like this meant some nurses might sometimes come across as “hard” and “cold”.If you came into [A&E] and a nurse started blubbering because of your story, what would you feel like as a patient? So, we probably are good at emotions but actually we’re good at not showing them. It doesn’t mean to say we don’t feel them … The more competent you become as a nurse, the more you actually learn that you have to suppress that … If you get a baby that comes in and the parents are screaming and crying, they don’t want the nurse doing the same thing. They want the nurse to be efficient, to know what they’re doing and to assist them. They do not need an emotional wreck to be dealing with them.

But being able to relate personally to the patient or their family, although helpful for the patient, can take a heavy toll on the nurse. One nurse got upset when telling me about the time she was pregnant with her little boy and was resuscitating a baby.

Compassion fatigueYeah. That was a baby. It sticks with you. It definitely does. I was looking after another one … that was having seizures. It was a one-year-old little one in resus, and when I finished my shift, I’d gone home, but it was on my mind all night and I was wanting to ring back and check. Obviously, I’ve got no connection to that little one … you can relate it to your own children as well, put yourself in those parents’ shoes.

Operational pressures in A&E and elsewhere in the health service squeeze the time nurses have with their patients. The fact many are unable to deliver the standard of care they long to contributes to nurses leaving the profession as described above.

And those nurses who stay can become so burned out that they can suffer with compassion fatigue: a protective mechanism in which nurses become emotionally “shut down” and as a result, can fail to notice and respond accordingly to trauma and suffering. This shows that the health – particularly the mental health – of nurses and doctors can directly impact patient care.

We need to understand the emotional complexity of nursing and other healthcare work. In understanding it, we can value it.

Nurses are not angels, they are human beings, with the accompanying full spectrum of emotions. At their best they can offer life-changing support and compassion. But they need the resources and support. There is only so much stress, fear, grief and trauma a person can cope with before burning out completely.

- My work investigating the links between viruses and Alzheimer’s disease was dismissed for years – but now the evidence is building

- Noise in the brain enables us to make extraordinary leaps of imagination. It could transform the power of computers too

- London’s Olympic legacy: research reveals why £2.2 billion investment in primary school PE has failed teachers

Kate Kirk, Lecturer in Organisational Behaviour in Healthcare, University of Leicester

It’s also about the future of our NHS and what we, are as a civilised society. Do we want a society which gives a helping hand to those suffering ill health and misfortune, which any one of us could suddenly find ourselves being; or do we want a dog-eat-dog and Devil take the hindmost society in which one person’s misfortune is a get-rich quick opportunity for someone else?

In short it’s about whether we want a kind, caring, civilised society or a nasty, greedy and selfish one to live and raise our families in.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.