Crucial Link in Primate Evolution - ScienceNOW

It's difficult to keep up with all this. Yet another 'transitional' fossil from the remote human evolution story has been found, this time in China, from 55 million years ago. Only last week I reported on a veritable deluge of reports and scientific papers reporting 'transitional' fossils such as early newts and turtles, and the finding that about eight percent of modern people have feet with characteristics found in an early hominin from South Africa, Australopithicus sediba, which itself had a skeleton which could only be regarded as transitional between fully bipedal hominins and the chimpanzees, from the period when our ancestors were evolving from a tree-dwelling to a ground-dwelling ape.

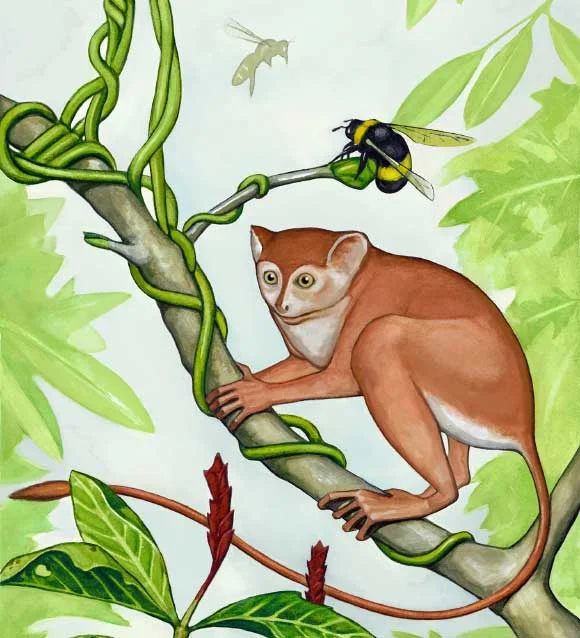

This little creature, which has been given the scientific name Archicebus achilles, has been extensively examined for the past ten years by a team of researchers who have concluded that it is the earliest primate so far discovered. Primates are the order of mammals which includes humans and the other apes as well as the monkeys, tarsiers, lorises, tree-shrews and lemurs. It was found in central China in the remains of an ancient lake bed and has been dated to 55 million years old.

While most other early primates are represented in the fossil record by a few teeth or a foot bone here and there, A. achilles looks remarkably good for its age. Its hind legs and nearly all the vertebrae in its long tail are strikingly well-preserved, giving scientists a clear picture of the animal's lower half. And with the help of powerful x-rays generated by the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, the researchers even managed to reconstruct key features of its partially crushed skull.

By comparing A. achilles's anatomy with the bodies of all other living and fossil primates, as well as a healthy number of closely related mammals, the team determined that it is most likely a very early ancestor of modern tarsiers, small nocturnal primates that today are found on only a handful of islands in Southeast Asia. With enormous eyes that help them see in the dark and long heel bones that facilitate powerful leaps, "tarsiers are like primates from Mars," says K. Christopher Beard, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and a co-author of the study. Still, scientists know that these strange creatures share a common ancestor with anthropoids, the group of primates that includes monkeys, apes, and humans. For decades, they've wondered how that common ancestor would have looked and behaved. Was it big like a monkey or small like a tarsier? Was it active during the day or did it lead a nocturnal life? What did it eat? And where did it live?

Because A. achilles "sits at that critical part of the tree right where the tarsier branch is splitting away from the anthropoid branch," Beard says, it can help scientists begin to answer those questions. For one, it was tiny. Weighing in at less than 1 ounce, A. achilles was smaller than any primate alive today, the team reports online today in Nature, adding support to the hypothesis that the earliest primates were diminutive, shrewlike creatures that fed on calorie-rich insects.

And although the existing evidence places the creature just slightly toward the tarsier branch of the primate family tree, A. achilles has some strikingly anthropoidlike features. Its feet, for example, were "a real shocker," Beard says. With relatively short toes and a short heel bone, they look almost exactly like the feet of small South American monkeys such as marmosets -- and almost nothing like modern tarsier feet...

"What this new fossil is telling us is that the common ancestor of tarsiers and anthropoids really was a hybrid," Beard explains. "It would not have been in any way completely monkeylike, but it certainly wasn't completely tarsierlike, either. It had certain features of both lineages already present."

Also significant is where A. achilles was found: China. The location of its discovery supports the once-controversial hypothesis that primates first evolved in Asia. When Beard first proposed that idea in the 1990s, he was "completely ridiculed," he recalls. "Everybody knew that everything in primate and human evolution occurred in Africa." But with a steady stream of early primate fossils being discovered in Asia, the field has gradually accepted that primates probably emerged there and only later migrated to Africa, where some groups eventually evolved to become humans.

Just as we saw with another transition primate fossil from 25 million years ago, the difficulty was in placing this specimen in the right branch of the evolutionary tree. Should it be regarded as a tarsier, or an anthropoid? This sort of discussion, which is always open to revision, review and debate, often hotly in specialist circles, which is so often ridiculed by the babbling Creationist baboons and held up as indecision and uncertainty, is exactly as it should be when the evidence is not conclusive. Unlike religion which has to make do with no evidence, science has no place for dogma. At the point of divergence in an evolutionary tree how can the evidence be anything but inconclusive? At that point in its evolutionary history, that particular branch hadn't metaphorically made a decision, so why would we expect scientists to make one?

The importance of this find is not just that it helps fix the time and place of a divergence in our branch of the family tree of life, but also, as Christopher Beard points out, that it adds a little more to the discussion about where the primate order evolved. This find supports the once unpopular, and still a minority view amongst palaeoanthopologists, that it happened in Asia. In this respect, note another characteristic of scientists and scientific debate - no one claims, or talks about proof. All conclusions are provisional and open to review, no matter how persuasive the evidence may be. Contrast this to religion where certainty is claimed and dogmatically demanded, and often woe betide any dissenters, on no evidence at all.

Note too that last paragraph:

Beard and his team are already working on a second round of analysis of A. achilles. Still, to draw firm conclusions about its role in primate evolution they'll need to find similarly well-preserved fossils of the tiny creature's closest relatives—a daunting task. "There was so little to compare this thing to," Beard says. "We've got this flag that we can plant for [A. achilles]. We need some more flags to plant nearby."

A nice example of how one discovery in science points to what else needs to be found. Science actively looks for gaps to close. How different that is to the creationist tactic of looking for gaps in which to sit their favourite god(s), widening them when necessary, and, when none are found, creating artificial ones. This is one amongst many ways that we can tell Creationism isn't science.

One wonders how much longer creationist loons and liars can continue before they chuck in the towel and concede defeat. If only it wasn't for all the money and control...

References:

Crucial Link in Primate Evolution; Lizzie Wade; Science 05 July 2013.

The oldest known primate skeleton and early haplorhine evolution; Xijun Ni, et al; Nature 498, 60–64 (06 June 2013) doi:10.1038/nature12200

Great article and analysis. It shows not only creationisms failings but also the beauty of the scientific method.

ReplyDeleteAnother example of how if you want to know the natural process of our evolution the evidence is clear to see. The beauty of our natural world will always trump some creationist with their swivelled eyed views.

ReplyDelete