A eucharist of sourdough or wafer? What a thousand-year-old religious quarrel tells us about fermentation

As though the idea of pieces of bread and/or wafer literally turning into bits of Jesus so they could be used in a cannibalistic ritual weren't absurd enough, in 1054, the Christian church erupted into a furious row almost amounting to civil war over the question not of whether the idea was too absurd to be believed but over the question of whether the bread should be made from sourdough or be unleavened!

The row widened and cemented the schism in the church over the correct dating of Easter which had arisen because no-one at the time the event it purports to commemorate - the alleged blood sacrifice of Jesus - thought it was significant enough to record. Later stories alluded vaguely to its relationship to the Jewish festival of Passover, with one account putting it on Passover itself on the Shabatt or Saturday at 9 o'clock in the morning (Mark 15:25), which would not have happened under Judaic law, and the other the day before, on the Day of Preparation, i.e., the day before Passover, on Friday at 12 noon. Unless there were two Jesuses, at least one of these dates and time is untrue.

Although that disagreement was the official reason for the schism, the real reason was of course the struggle for control of the church between the capitals of the old Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek), Rome and Constantinople (or Byzantium) respectively, because Christianity was nothing if not a political front based on the philosophy that to control the people you had to control their religion. The Latin west was never going to accept Greek rule from Constantinople and the Greek east was never going to accept Latin rule from Rome.

So, what was the row about the right type of bread to be magically turned into bits if Jesus all about and why was it elevated to such a high level of importance?

In the following article, reprinted from The conversation under a Creative Commons license, Robert Nelson, Honorary Principal Fellow, The University of Melbourne, Australia explains how it became a matter of the authority of the respective churches. His article has been reformatted for stylistic consistency:

A eucharist of sourdough or wafer?

What a thousand-year-old religious quarrel tells us about fermentation

What a thousand-year-old religious quarrel tells us about fermentation

A Byzantine depiction of the Eucharist in Saint Sophia Cathedral, Kyiv.

Robert Nelson, The University of MelbourneA nasty quarrel arose in the 11th century over what kind of bread should be used in holy communion.

The view in Constantinople was the bread for the eucharist must be sourdough. But in Rome, an unleavened wafer had been used for longer than anyone could remember and the Vatican argued unleavened bread was more authentic.

It might sound like a storm in a chalice, but it mattered a lot because church authority seemed to be at stake.

Neither side could back down, and the grand fracas – known as the “azyme controversy of 1054” – became so divisive that it led, among other quibbles, to the schism of east and west. Today, the sourdough loaf in the Orthodox liturgy is cut up and mixed with wine, while the Catholic church still uses a small circular wafer.

Scholars have difficulty accounting for this unfortunate brawl. Was it politically motivated, or just an escalation of insults among bickering headstrong men that’s best forgotten?

But rather than reading the controversy as a case study in antagonism, it occurred to me the historical record is useful in illuminating medieval attitudes to bread and fermentation.

Christ’s sacrifice

The Byzantine Greeks had a gut reaction to the Latin wafer or matzo (azymon). They were disgusted by the idea of an inflexible board representing the Saviour. The Lord’s body had to be figured in a more flesh-like genuine bread.

They accused the Latin wafer of being like the clay of a brick; the Latin unleavened bread as being “dead” (nekron). Even in the 8th century, John of Damascus described this characterless wafer as “insipid” (moron).

Much of the debate concerned doctrine.

The Byzantines thought the Latins didn’t really understand the point of the sacrament, because their unleavened bread was a throw-back to Jewish practice. The Byzantines said they must not Judaicise (ioudaïzein) the holiest rite, which is all about Christ’s sacrifice that Jews don’t recognise.

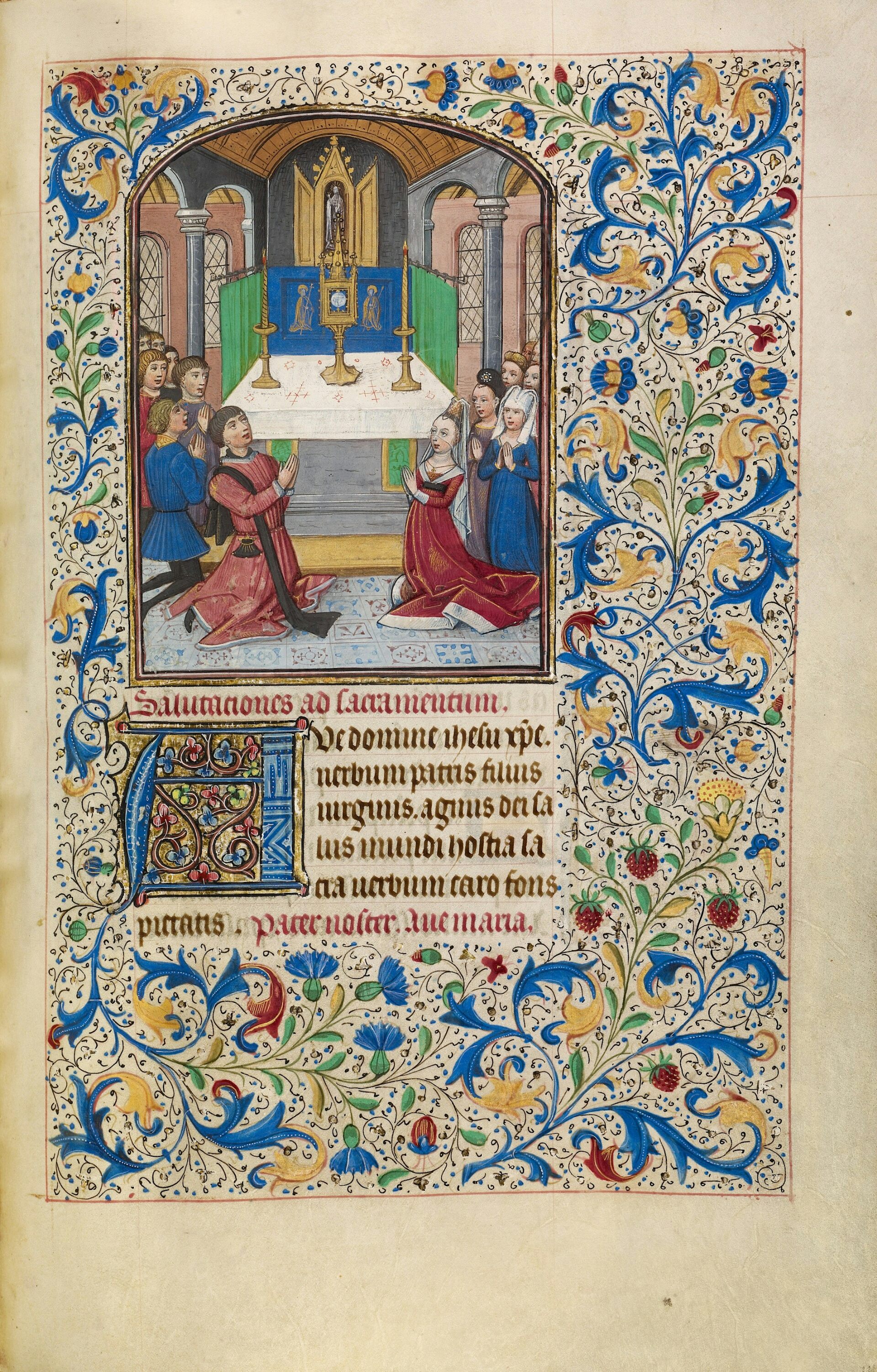

The Adoration of the Eucharist, early 1460s, Willem Vrelant (Flemish, died 1481, active 1454– 1481).

The Latin church retorted the fermentation of the dough introduces an impurity into the angelic substance of the eucharist. After all, they said, the process of sourdough must be a bit like rot or putrefaction.

It seemed to them the original unadulterated ingredients of wheat and flour are sullied by (the then) unknown alien substance that eventually results in degradation and spoiling (vitiatio).

Observing the yeast

Behind this disagreeable theological dispute between eastern and western churches, we gain precious insight into how the premodern mind understood fermentation, and especially what distinguishes it from rot and decay.

The debate brings out intuitions that anticipate the findings of Louis Pasteur 800 years later, who understood the action of yeasts as an additive process rather than a form of decay.

Actually, the positive interpretation of yeast begins with Jesus himself. In a Biblical verse quoted repeatedly during the squabble, Jesus compares heaven to sourdough:

The kingdom of heaven is like unto leaven (zyme), which a woman took, and hid in three measures of meal, till the whole was leavened.As the Byzantines argued, Jesus wouldn’t have proposed this analogy if he thought the leaven was some form of corruption that takes over and damages the food.

His parable envisages good things (think divine love) spreading miraculously in the holy environment, in the same way the lump of dough is enriched by the discrete amounts of leaven that end up permeating it.

The Byzantines and Pasteur would agree with Jesus. Following Pasteur, we identify the wild yeast in sourdough as lactobacillus – but there was no microscope in the middle ages and a scientific approach could only be based on what could be seen, which is marvellously enigmatic.

The Latin view rejected the homely Greek interpretation. Their Vulgate Bible mistranslates a line of Paul, saying “a little leaven spoils (corrumpit) the whole lump”, instead of “a little leaven leaveneth (zymoi) the whole lump”.

A belligerent Cardinal Humbert dismissed the analogy of heaven and leaven, scoffing that Jesus also compares heaven to a seed of mustard.

Humbert argued the yeast in the leaven has to come from somewhere: its origins belong with similar yeasts in beer, and these in turn are related to the scum of foul organic matter.

Humbert also reminds us of what happens when you leave the leavened dough for too long: it goes off and becomes inedible.

Heavenly sourdough

Today we might say that the Latins came to the wrong biochemical conclusions, but in many ways their approach was more empirical and scientific. Observing how leavened dough easily becomes foul, they reasoned that fermentation must involve impurities.

For those of us who haven’t looked at a microscope since high school, the Byzantine polemic in general helps us understand how we still imagine microbiological processes without being able to see or name the various bacteria and enzymes at work.

Even after peak sourdough during the lockdowns, sourdough strikes me as mysterious as a process and seductive in its results, with a tough texture and pleasantly sour taste arising from unseen bugs.

And though our secular bakers are remote from the passionate theology of Byzantine clerics, we know deep down that sourdough is heavenly and the most charismatic of breads.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If there is disagreement about the authenticity of St Paul's 'epistles' which ones are now accepted as forgeries? The authenticity of some of the letters attributed to St. Paul in the New Testament has been a subject of scholarly debate for centuries. While there is general consensus among scholars regarding the authenticity of some of the letters traditionally attributed to Paul, there are a few that are widely considered to be forgeries or pseudepigrapha (writings falsely attributed to an author). The letters that are commonly believed to be authentic, or at least written by Pauline communities in his name, include:And all over what is the best substance to be magically turned, with magic spells and special hand signs by people wearing special robes, into real pieces of Jesus to be eaten in a cannibalistic ritual involving eating bits of wafer-flavoured Jesus washed down with a mouthful of wine-flavoured real blood.However, there are a few letters attributed to Paul in the New Testament that are disputed or considered by many scholars to be forgeries:

- Romans

- 1 Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians

- Galatians

- Philippians

- 1 Thessalonians

- Philemon

It's important to note that scholarly opinions on these matters can vary, and there's ongoing debate within biblical studies regarding the authorship of these letters. Additionally, some scholars argue for a more nuanced understanding of authorship, suggesting that even if Paul didn't personally write some of these letters, they may still reflect the teachings and traditions associated with him and his communities.

- Ephesians: Many scholars doubt Pauline authorship of Ephesians due to differences in style, vocabulary, and theological emphasis compared to the undisputed Pauline letters.

- Colossians: Similar to Ephesians, Colossians is often questioned for its style and theology, leading some scholars to suggest it was written by a later follower of Paul.

- 2 Thessalonians: While some scholars accept the authenticity of 2 Thessalonians, others argue that its style and content raise questions about Pauline authorship.

- 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus (the Pastoral Epistles): These letters are widely regarded as pseudepigraphical, meaning they were likely written by a later author who attributed them to Paul. The theological and linguistic differences from the undisputed Pauline letters, as well as historical references inconsistent with Paul's life, contribute to this view.

No wonder Christians could be so easily persuaded to commit atrocities over the years when they were required to abandon reason and believe such absurdities.

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

If you need a bread that contains enough minerals, biological nutrients to make human flesh - then I think a seeded farmhouse bread would be the best option.

ReplyDeleteLOL!

Delete