Religion, Creationism, evolution, science and politics from a centre-left atheist humanist. The blog religious frauds tell lies about.

Friday, 15 December 2023

Creationism in Crisis - Human Intelligence Is Not So Much A Matter of Quantity But Of Quality

Human intelligence: how cognitive circuitry, rather than brain size, drove its evolution

Researchers have shown that human intelligence does not depend primarily on the size of our brain - there are animals with bigger brains (elephants, orcas) - but on the cognitive circuitry.

The team, led by Valentin Riedl of the Department of Neuroradiology at Klinikum rechts der Isar, TUM School of Medicine and Health, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, have published their findings, open access, in the journal Science Advances. It is explained in an article in The Conversation by two Cambridge University professors who were not involved in the research.

Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Thursday, 14 December 2023

Unintelligent Design - Why Some Women Experience Morning Sickness during Pregnancy.

1-3% are severe enough to require hospital treatment

Why seven in ten women experience pregnancy sickness

'Morning sickness, which is common in the earlier stages of pregnancy, and which, in its more severe form, hyperemesis gravidarum, can be seriously debilitating and may even require admission to hospital and iv fluids to prevent life-threatening dehydration, is now known to be caused by a protein hormone, known as GDF15, produced by the foetal part of the placenta.

This discovery, published yesterday in Nature, by a team from Cambridge University, UK, led by Professor Sir Stephen O’Rahilly, and including researchers in Scotland, the USA and Sri Lanka, points to a potential way to prevent pregnancy sickness by exposing mothers to GDF15 ahead of pregnancy to build up their resilience.

It had previously been suggested that GDF15 might be acting on the mother's brain to make her feel nauseous. This has now been confirmed and found to be dependent on two factors:

- How much of the hormone is being produced.

- How sensitive to it the mother's brain is.

The team arrived at this conclusion after obtaining data from women recruited to a number of studies, including at the Rosie Maternity Hospital, part of Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Peterborough City Hospital, North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust. They used a combination of approaches including human genetics, new ways of measuring hormones in pregnant women’s blood, and studies in cells and mice.

The team found that a rare genetic variant that puts women at a much greater risk of hyperemesis gravidarum was associated with lower levels of the hormone in the blood and tissues outside of pregnancy. Similarly, women with the inherited blood disorder beta thalassemia, which causes them to have naturally very high levels of GDF15 prior to pregnancy, experience little or no nausea or vomiting.

Most women who become pregnant will experience nausea and sickness at some point, and while this is not pleasant, for some women it can be much worse – they’ll become so sick they require treatment and even hospitalisation. We now know why.

The baby growing in the womb is producing a hormone at levels the mother is not used to. The more sensitive she is to this hormone, the sicker she will become.

Knowing this gives us a clue as to how we might prevent this from happening. It also makes us more confident that preventing GDF15 from accessing its highly specific receptor in the mother’s brain will ultimately form the basis for an effective and safe way of treating this disorder.

Co-Director of the Institute of Metabolic Science

and Director of the Medical Research Council Metabolic Diseases Unit

University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

When I was pregnant, I became so ill that I could barely move without being sick. When I tried to find out why, I realised how little was known about my condition, despite pregnancy nausea being very common.

Hopefully, now that we understand the cause of hyperemesis gravidarum, we’re a step closer to developing effective treatments to stop other mothers going through what I and many other women have experienced.

Center for Genetic Epidemiology

Department of Population and Public Health Sciences

Keck School of Medicine

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Their problem is compounded by the fact that, in this case, they can't blame it all on 'Sin' and let their little pet good off the hook, because the culprit, GDF15, has several important functions unrelated to pregnancy, so the side effects such as morning sickness and hyperemesis gravidarum appear to be an unforeseen consequence of it. No intelligent [sic] designer worthy of the name, especially a reputedly omniscient, omnipotent one, would design a protein hormone with unforeseen consequences, so we have to assume either it knew what it would do and didn't care, or it knew what it would do and designed it for that purpose. Briefly, GDF15 does the following:

What biological function does the hormonal protein GDF15, have? Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF15) is a protein that plays a role in various biological processes, particularly in the regulation of energy balance and metabolic functions. Here are some key aspects of GDF15's biological functions:So, creationists have a three-way choice here: Is this a result of:The exact mechanisms through which GDF15 exerts its effects are still an active area of research, and its functions can vary in different physiological and pathological conditions. It's important to note that the understanding of GDF15's functions is continually evolving as new research findings emerge.

- Appetite Regulation: GDF15 is known to act as a satiety signal, meaning it can reduce appetite and food intake. It is produced in response to conditions such as inflammation, tissue damage, or cellular stress, and it signals to the brain to decrease food consumption.

- Metabolic Regulation: GDF15 has been implicated in the regulation of metabolism. It can influence energy expenditure and may contribute to the control of body weight. Its levels are often elevated in conditions associated with weight loss, such as cancer or certain chronic diseases.

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: GDF15 has anti-inflammatory properties and can modulate the immune response. It may play a role in limiting excessive inflammation during certain physiological or pathological conditions.

- Cardioprotective Effects: GDF15 has been associated with cardioprotective effects. Elevated levels of GDF15 are often observed in response to cardiovascular stress, and it may have a role in protecting the heart and blood vessels.

- Cancer-Related Functions: GDF15 is expressed in various tissues, and its levels are often increased in certain types of cancer. It may have both tumor-suppressive and tumor-promoting effects, depending on the specific context and type of cancer.

- Incompetence?

- Malevolence?

- Evolution?

Wednesday, 13 December 2023

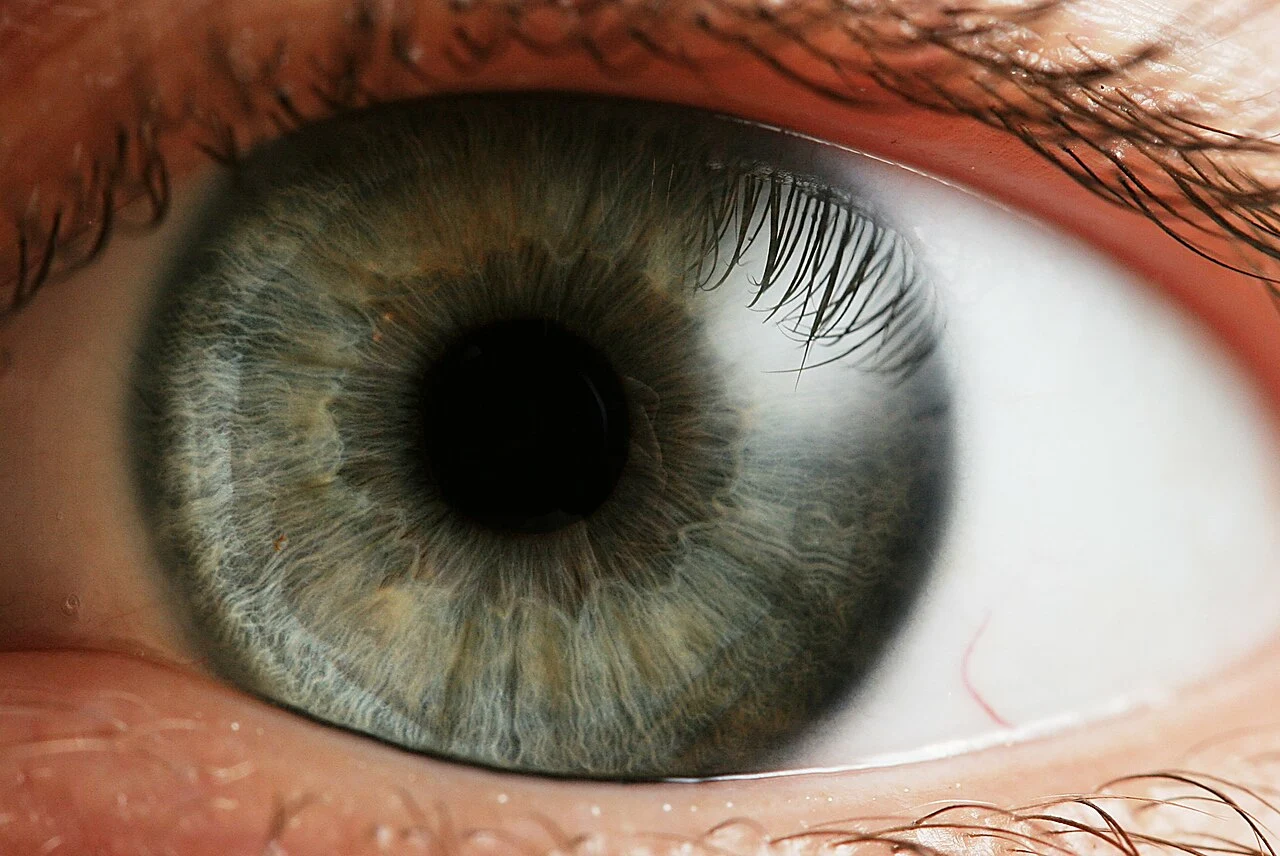

Creationism in Crisis - The Evolution of the Mammalian Eye From A Common Origin Over 400 Million Years Before 'Creation Week'.

Cell types in the eye have ancient evolutionary origins | Berkeley

Despite the claims of creationists frauds who cite Charles Darwin, whom they falsely claim admitted the structure of the eye couldn't be explained, the evolution of the mammalian eye from a simple patch of light-sensitive cells is well known to biological science.

Darwin, of course, was setting out the problem before explaining the solution in a typical literary technique of his time. The paragraph that creationists often try to get away with citing is:

To suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree.

What they always fail to cite is the very next paragraph:

Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly, and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly be considered real.

And now we know that different eyes exist or have existed in nature, such as the compound eyes of the arthropods, the unique silica-based eye of the trilobites, the cephalopod eye of the octopus/squid class, the simple eye-spots of molluscs and the vertebrate eye, so evolved on several occasions in different taxons.

This refutation of creationism deals with the evolution of the mammalian eye and in particular the different specialist cells of the retina. These have the origins in the eyes of the first jawed vertebrates over 400 million years ago. It is the work of Karthik Shekhar and colleagues from the University of California, Berkeley and a group led by Joshua Sanes at Harvard University. Their work is published open access in Nature as part of a 10-paper series reporting the latest results of the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network's efforts to create a cell-type atlas of the adult mouse brain.

By examining the eyes from 17 separate species, including humans, the team showed that certain cell types are highly conserved and must have been present in the stem mammal from about 200 million years ago, which had a retina as complex as that of modern mammals, and some had their origins over 400 million years ago in the common ancestors of all mammals, birds, reptiles amphibians and jawed fish.

From the UC Berkley news release:

The findings were a surprise, since vertebrate vision varies so widely from species to species. Fish need to see underwater, mice and cats require good night vision, monkeys and humans evolved very sharp daytime eyesight for hunting and foraging. Some animals see vivid colors, while others are content with seeing the world in black and white.

Yet, numerous cell types are shared across a range of vertebrate species, suggesting that the gene expression programs that define these types likely trace back to the common ancestor of jawed vertebrates, the researchers concluded.

The team found, for example, that one cell type — the "midget" retinal ganglion cell — that is responsible for our ability to see fine detail, is not unique to primates, as it was thought to be. By analyzing large-scale gene expression data using statistical inference approaches, the researchers discovered evolutionary counterparts of midget cells in all other mammals, though these counterparts occurred in much smaller proportions.

"What we are seeing is that something thought to be unique to primates is clearly not unique. It’s a remodeled version of a cell type that is probably very ancient," said Shekhar, a UC Berkeley assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering. "The early vertebrate retina was probably extremely sophisticated, but the parts list has been used, expanded, repurposed or refurbished in all the species that have descended since then."

[…]

The discoveries are, in a sense, not a total surprise, since the eyes of vertebrates have a similar plan: Light is detected by photoreceptors, which relay the signal to bipolar, horizontal and amacrine cells, which in turn connect with retinal ganglion cells, which then relay the results to the brain's visual cortex. Shekhar uses new technologies, in particular single-cell genomics, to assay the molecular composition of thousands to tens of thousands of neurons at once within the visual system, from the retina to the visual cortex.

Because the number of identified retinal cell types varies widely in vertebrates — about 70 in humans, but 130 in mice, based on previous studies by Shekhar and his colleagues — the origins of these diverse cell types were a mystery.

One possibility that emerged from the new research, Shekhar said, is that as the primate brain became more complex, primates began to rely less on signal processing within the eye — which is key to reflexive actions, such as reacting to an approaching predator — and more on analysis within the visual cortex. Hence the apparent decrease in molecularly distinct cell types in the human eye.

"Our study is saying that the human retina may have evolved to trade cell types that perform sophisticated visual computations for cell types that basically just transmit a relatively unprocessed image of the visual world with the brain so that we can do a lot more sophisticated things with that," Shekhar said. "We are giving up speed for finesse."

AbstractNot only is the tired old creationists lie that Darwin admitted the evolution of the eye couldn't be explained refuted, but the evolution of the eye has its origins way back in that 'pre-Creation Week' history when all the major events in Earth's long history occurred.

The basic plan of the retina is conserved across vertebrates, yet species differ profoundly in their visual needs1. Retinal cell types may have evolved to accommodate these varied needs, but this has not been systematically studied. Here we generated and integrated single-cell transcriptomic atlases of the retina from 17 species: humans, two non-human primates, four rodents, three ungulates, opossum, ferret, tree shrew, a bird, a reptile, a teleost fish and a lamprey. We found high molecular conservation of the six retinal cell classes (photoreceptors, horizontal cells, bipolar cells, amacrine cells, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and Müller glia), with transcriptomic variation across species related to evolutionary distance. Major subclasses were also conserved, whereas variation among cell types within classes or subclasses was more pronounced. However, an integrative analysis revealed that numerous cell types are shared across species, based on conserved gene expression programmes that are likely to trace back to an early ancestral vertebrate. The degree of variation among cell types increased from the outer retina (photoreceptors) to the inner retina (RGCs), suggesting that evolution acts preferentially to shape the retinal output. Finally, we identified rodent orthologues of midget RGCs, which comprise more than 80% of RGCs in the human retina, subserve high-acuity vision, and were previously believed to be restricted to primates2. By contrast, the mouse orthologues have large receptive fields and comprise around 2% of mouse RGCs. Projections of both primate and mouse orthologous types are overrepresented in the thalamus, which supplies the primary visual cortex. We suggest that midget RGCs are not primate innovations, but are descendants of evolutionarily ancient types that decreased in size and increased in number as primates evolved, thereby facilitating high visual acuity and increased cortical processing of visual information.

Hahn, J., Monavarfeshani, A., Qiao, M. et al.

Evolution of neuronal cell classes and types in the vertebrate retina.

Nature 624, 415–424 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06638-9

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

No wonder so many former creationists realised that a cult that needs to lie to its members to keep them in the cult is not a cult worth belonging to.

Creationism in Crisis - How Wrong The Bible's Authors Were! Why Would Anyone Believe Anything Else They Wrote?

D. Milisavljevic (Purdue University),

T. Temim (Princeton University),

I. De Looze (University of Gent)

NASA’s Webb Stuns With New High-Definition Look at Exploded Star - NASA

The description of the Universe in the Bible is so naïve and radically different to the real universe, it beggars belief that there are grown adults who think the Bible is the inerrant word of a creator god.

There is nothing about the authors' description of it which can be described as allegorical or metaphorical, without the most contorted of mental gymnastics. It is not metaphorical or allegorical; it is quite simply wrong; spectacularly and conspicuously, with no shadow of a doubt, wrong!

What we now know are hundreds of billions of galaxies, each with maybe half a trillion stars, many with planetary systems, the authors of the Bible thought were little lights stuck to the underside of a dome over a flat Earth, that can be shaken loose and will fall down to Earth where they can be trampled on by a goat! (Daniel 8:10).

They described this flat Earth with a dome over it as standing on pillars and the fixed and immobile center of the Universe, round which a small sun orbits. They described the sky above the dome as being made of water. Their universe ran on magic.

Tuesday, 12 December 2023

Creationism in Crisis - Here Be Monsters! - 72 Million Years Before Creation Week

Today's scientific refutation of the childish creationists superstition that even some otherwise normal adults still believe in, comes from a paper published in Journal of Systematic Palaeontology by Associate Professor Takuya Konishi of Cincinnati University and an international team of co-authors.

It describes a giant mosasaur the size of a great white shark that hunted in the Pacific seas, 72 million years before creationist dogma says Earth was created. And this is no ordinary mosasaur but displays a number of features that show how a similar environment and lifestyle can lead to parallel evolution, just as the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection predicts.

These mosasaurs have a dorsal fin, just like the only very distantly-related bony fish, sharks (cartilaginous fish), and whales and dolphins. This gives them greater control and mobility in water.

This species of mosasaur was named after the place where it was found (Wakayama Prefecture, Japan) and a mythical creature from Japanese folklore, Soryu (blue dragon).

According to the press release from Cincinnati University:

Sunday, 10 December 2023

Creationism in Crisis - What A Juvenile Tyrannosaurid Was Eating 75 Million Years Before 'Creation Week'

Royal Tyrrell Museum

What’s for dinner? UCalgary paleontologist finds out through remarkable specimen | News | University of Calgary

75 million years before creationists think Earth was created, a juvenile Gorgosaurus, a species of tyrannosaur, was catching young avian dinosaurs like Cities but then selectively eating the fleshiest parts, the legs.

At this stage in its life, the Gorgosaurus was slender, had a narrow skull and blade-like teeth and was able to catch small, swift running dinosaurs, but had it lived to grow into an adult, it's body and particularly its head and teeth, would have become massive and capable of catching the large vegetarian dinosaurs and crushing their bones.

We know this because this particular juvenile Gorgosaurusdied and its body became fossilised, complete with the leg bones of two young Citipes still in its stomach, one more digested than the other, showing they were eaten at different times.

This was discovered by a group of palaeontologists led by Dr. Darla Zelenitsky, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Earth, Energy and Environment at the University of Calgary, and Dr. François Therrien from the Royal Tyrrell Museum. Their finding is published, open access, in the journal Science Advances. It is described in a University of Calgary news item:

Saturday, 9 December 2023

Unintelligent Design - The Late Devonian Mass-Extinction Or How Earth Is Badly Designed For Life

Way back 370 million years before the mythical 'Creation Week' the seas were full of life and angiosperm plants were rapidly replacing the tree ferns and other Tracheophytes and life was looking good, despite the fact that the single large landmass, Pangea, was on the point of breaking up.

Then something happened to cause another of those periodic mass extinctions that have punctuated Earth's long 'pre-Creation' history. What exactly it was has been the subject of ongoing debate by geologists, biologists and climatologists ever since evidence of it was found in the fossil record, particularly in Devonian rocks like those in Greenland.

But whatever the cause, it's not good news for creationists who have been duped by their cult leaders into believing Earth is fine-tuned for life by a designer god, and, by the circular reasoning that characterises creationism, therefore this fine-tuning 'proves' their designer god exists. A cynic might wonder, if faith is any good, why creationists are so desperate to find scientific 'proof' of their god that they perform all manner of ludicrous mental gymnastics and commit just about every logical fallacy in the book, to tell themselves and their target dupes that they have discovered it - and will be producing it any day now, real soon!

But that's by the by.

Sadly for creationists the evidence is that Earth is anything but finely tuned and perfect for life. The simple truth is that an Earth that was perfectly designed for life would never have extinctions, let alone mass extinctions like the ones that ended the Devonian and Cretaceous eras, and the one that's in progress right now. In fact, there would not even be biodiversity on such a planet because there would be no reason to adapt to adverse conditions because since these would not exist on a perfectly designed Earth, so life would not have progressed beyond the simplest of self-replicating molecules.

So, just for any creationists still under the delusion that Earth is finely tuned for life, here is a brief description of the Devonian and the mass extinction at the end of it:

Creationism in Crisis - How De Novo Genes Arise (And Another Creationist Dogma Bites The Dust)

New genes can arise from nothing | HiLIFE – Helsinki Institute of Life Science | University of Helsinki

Present a creationist with a puzzle like, where does new genetic information in the form of new functional genes come from and a typical response will be, "Er... I can't imagine how that's possible... so God did it!". This of course is based on the foundational fallacies of creationism, and most religious apologetics - the argument from ignorant incredulity, and the false dichotomy fallacy.

This intellectual dishonesty appeals to people who are satisfied with not knowing and aren't bothered about the truth, so long as they have an excuse for pretending they know the answer

By contrast, present a scientist with the same question, and the response will probably be, "I don't know, so how can we find out?", because admitting ignorance is the foundation of good science. This approach appeals to people who have the humility to admit they don't know and who are interested enough in truth to want to find out.

An example of this was published recently by three researchers from the Institute of Biotechnology, Helsinki Institute of Life Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, who decided to address the question of where de novo genes arise in the genome, seemingly from nowhere.

This question arose from the observation that a comparison between human and other primate genomes shows that a number of microRNA (miRNA) sequences arose within the human genome, and the genome of other apes apparently as single mutation events.

In addition to the 20,000 genes in the human genome, there are thousands of miRNA sequences of about 22 base-pairs which have a regulatory function. Their role is to stop messenger RNA (mRNA) from continuing to make proteins when enough have been made. They do this by blocking the mRNA molecules and to do this they need to be folded in half like a hairpin. This folding means that they need to be 'palindromes', i.e., reading the same forward as backward, so, when folded in half, each base lines up with a copy of itself.

So, the question was, how do these palindrome miRNAs arise?

Friday, 8 December 2023

Creationism in Crisis - Chemical Fossils Show How Life Evolved Over A Billion Years Before 'Creation Week'

via Getty Images

A simplified animal phylogeny, with the hypothesized presence of smt visualized with blue lines. This tree provides a conservative estimate of the number of smt losses, as it excludes many understudied animal phyla that may also lack the protein.

Early organisms, particularly from before animals with hard body parts like teeth, bones and hard exoskeletons had evolved, leave few traces in the fossil record, but that's not to say they leave no trace whatsoever. What they leave is a chemical signature in the rocks that can last for hundreds of millions, even billions of years.

Sterol lipids, for example are highly stable chemicals that come from cell membranes and can be found in rocks dated to 1.6 billion years old. Since they can only be produced by living organisms, they are compelling evidence for the existence of life when those rocks were laid down.

In the present day, most animals use cholesterol — sterols with 27 carbon atoms (C27) — in their cell membranes. In contrast, fungi typically use C28 sterols, while plants and green algae produce C29 sterols. The C28 and C29 sterols are also known as phytosterols.

C27 sterols have been found in rocks 850 million years old, while C28 and C29 traces appear about 200 million years later. This is thought to reflect the increasing diversity of life at this time and the evolution of the first fungi and green algae.

Early organisms needed to synthesise their own sterols and did so using a gene called smt, but, as more sources of sterols became available by eating fungi and algae, so this gene became redundant and was eventually lost from many evolutionary lines. When this gene disappeared from these lines shows when they began consuming these new sources of sterols.

By constructing a family tree for this gene using data from first annelids then across animal life in general, the UCDavid team were able to map when this gene was lost onto changes in the sterol record in rocks - and they mapped closely to the chemical record in the rocks.

According to a news release from the University of California Davis (UCDavis), where David Gold, associate professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary works in this new field of molecular paleontology, using the tools of both geology and biology to study the evolution of life:

Thursday, 7 December 2023

Unintelligent Design News - How A Badly Designed Protein Causes Autoimmune Diseases

Fungus-fighting protein key to overcoming autoimmune disease and cancer | Australian National University

The more you learn of creationism's putative intelligent [sic] designer, the more like William Heath Robinson it becomes.

The main difference is that, no matter how ramshakled they were, William Heath Robinsons inventions actually worked, even if they didn't produce the required result. The same can't be said for creationism's god's designs. They resemble piecemeal designs where each part is designed in isolation in response to a problem, often a problem somewhere else in the design, where near enough is good enough and there is no joined up thinking.

Rather like a William Heath Robinson machine, conbbled together from disparate parts, but where when a knotted piece of string breaks, instead of replacing it with a new piece of string or tying the broken ends together, like Heath Robinson would, a different, weaker sort of string is designed and tied across the broken ends, but then that keeps breaking too.

An example of this inept design was discovered recently and found to be the cause of autoimmune diseases such as iritable bowel syndrome (IBS), type 1 diabetes, eczema and other chronic disorders. The problem is with a protein called DECTIN-1 (also known as CLEC7A) which is producd by the immune system in response to fungal infections. Researchers at The Australian National University (ANU) have discovered that a mutated form of DECTIN-1 limits the production of T regulatory cells or so-called ‘guardian’ cells in the immune system.

Mutations arise, of course, because of another poor design - the process for replicating DNA, which is so prone to errors that another mechanism for repairing it is needed. However this is also prone to errors, the result of which means that many of our cells carry mutations, some of which cause cancers.

The research is publshed in Science Advances and ex[lained in an Australian Nationa University News release:

Creationism in Crisis - A 15 Million-Year-Old Former Lake in Southern Germany Is Drowning Creationism With Facts

15 million years before 'Creation Week', when creationists think Earth was magically created out of nothing, a meteorite struck in what is now southern Germany, just north of the Danube, creating a circular crater that filled with water to form a lake, in an area surrounded by the hills known as the Nördlinger Ries.

Now the sedimentary rocks formed on the lakebed are revealing their locked-up record of the geological and biological changes in the intervening 15 million years of Earth's 'pre-Creation' history.

They are also providing useful information about what any signs of life in Martian craters might look like.

First, a little AI information about Nördlinger Ries:

Wednesday, 6 December 2023

Malevolent Designer News - How A Bacterium Is 'Intelligently Designed' To Turn Plants Into Zombies

From Infamy to Ingenuity – Bacterial Hijack Mechanisms as Advanced Genetic Tools | John Innes Centre

Scientists working at the John Innes Centre, Norwich, Norfolk, UK., have worked out the sneaky way a bacterium converts an internal cell mechanism in plants to suit its own purpose at the expense of the host, in another example of how a parasite can zombify its host.

Creationists looking at this mechanism from the arrogant perspective that sees their own ignorant incredulity as scientific data, would conclude that it must be intelligently designed, but would then need to perform intellectual summersaults to explain why, even though their own putative creator god is the only supernatural entity capable of designing complex living organisms, something called 'Sin' also creates complex living organisms, so their omnipotent god is not responsible for parasites.

The parasitic Phytoplasma bacterium is transmitted by insects and causes diseases like Aster Yellows, significantly diminishing yields in leaf crops including oilseed rape, lettuce, carrots, grapevines, onions, and a variety of ornamental and vegetable crops worldwide. It is also responsible for the familiar 'witches' brooms' in trees in which the plant produces a proliferation of thin branches and leave.

How it does this is explained in an open access research paper in PNAS. It does it by hijacking the protein recycling function of a cell organelles, the 26S proteasome, so first a little AI background about the 26S proteasomes:

Creationism in Crisis - Humans and Other Apes Are Born With Similar Brains

Brains of newborns aren't underdeveloped compared to other primates | UCL News - UCL – University College London

Scientists are revising what was believed about the state of development of a human baby's brain at birth compared to that of a newborn Chimpanzee - but not in a way that brings any comfort to creationists.

This research compares the brain development of a human baby with that of other apes because the scientists have no doubt that humans are apes, so comparisons are scientifically valid.

It had been thought that a newborn human's brain was underdeveloped, or altricial, compared to the other apes, but this paper shows that to be a false impression caused by the fact the a human baby's brain grows more quickly and becomes more complex than that of our close relatives, however, the starting point is very similar to that of a chimpanzee.

The paper by researchers Aida Gómez-Roblesa and Christos Nicolaou of the Department of Anthropology, University College London (UCL) together with colleagues Jeroen B. Smaers of the Department of Anthropology, Stony Brook University, New York, USA and Chet C. Sherwood of the Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, is published open access in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The research and its significance are explained in a UCL News release:

Unintelligent Design - Or Is It Malevolence? How Bacteria Are Designed to Exploit Our Mucus

Bacteria's mucus maneuvers: Study reveals how snot facilitates infection | Penn State University

The mucous membrane lining our respiratory system has evolved (or, according to creationists, been intelligently [sic] designed) to keep our respiratory system clean as we breathe in air containing particles of dirt, dust, pollen and bacteria. It does this by secreting mucus that traps the particles, then ciliated cells on the surface sweep them towards our pharynx to be swallowed and disposed of in our digestive system where the proteins in the mucous are recycled.

Other body cavities are lined by a mucous membrane that serves to protect and keep the cavity moist and lubricated.

But, in one of those research papers that creationists have to avoid reading, a team of researchers from Penn State University, have shown how bacteria have evolved (or been intelligently [sic] designed, according to creationists) to exploit the mucous, the better to infect us and make us sick, and the thicker the mucus, the better it is for these would-be pathogens.

Infections by bacteria, known medically as opportunist infections, especially in the nasal sinuses and lungs, are a frequent complication of viral infections such as a common cold or influenza. These opportunist infections can be more dangerous than the virus infections that facilitate them.

The team showed that bacteria find it easier to swim, swarm and form colonies in thick mucus than in thin, watery mucus and that this swarming probably helps protect them from the antibacterial enzymes in the mucus.

Their research is explained in a Penn State news release:

Creationism in Crisis - A Monster Virus Is A BIG Problem For Creationists

Pithoviruses Are Invaded by Repeats That Contribute to Their Evolution and Divergence from Cedratviruses | Molecular Biology and Evolution | Oxford Academic

Regular readers with very long memories may remember how I wrote about something big and potentially nasty emerging from Siberian permafrost back in 2014.

The 30,000-year-old monster in question was a form of giant virus then unknown to science, now named Pithoviruses sibericus. It came back to life when thawed. Since then, several other related pithoviruses have been discovered in soil and aquatic sources. Fortunately, all those discovered so far are parasitic only on one species of amoeba, Acanthamoeba castellanii and don't pose a threat to humans or multicellular life.

The question was, why are they so large, or more particularly, why do they have such a massive genome, including some genes normally found in complex cells. the Pithovirus species so far discovered have a genome of between 460 to 686 kb. Their genome, moreover, is similar to that of bacteria and archaea, in that it is DNA-based and forms a single circular 'chromosome'.

But it's not the fact that the first one was found in permafrost dating back 20,000 before 'Creation Week', difficult though that little inconvenience is for creationists; it is the account of how they acquired this massive genome that is the thing of nightmares for any creationists who understand the biology.

They acquired it by processes that give the lie to their basic dogma that new genetic information can't arise in a genome without 'God magic'.

A team of researchers have shown that they acquired new genetic information and such a massive genome by:

- Horizontal gene transfer (5% -7 %)

- Gene duplication (14% - 28%)

- Massive inversions of repeated sequences of DNA.

And this gives the lie to the ludicrous creationist dogma that no new information can arise by mutation because all mutations are deleterious. There is nothing deleterious in having a spare copy of a gene, nor in mutations in that spare copy, least of all if it gives a new function that increases fitness.

The researchers, from the Institut de Microbiologie de la Méditerranée, FR3479), IM2B, IOM, Aix–Marseille University, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Marseille, France were led by Matthieu Legendre. Their findings are published, open access, in Molecular Biology and Evolution:

Tuesday, 5 December 2023

Creationism in Crisis - Evolution of Rock Doves & Domestic Pigeons

A great deal is understood about how the many different varieties of domestic pigeon were produced ever since Charles Darwin used them to illustrate the role of selection in evolution. In this case, selection is human selection rather than natural selection, although the difference is a matter of semantics if you regard human selective breeders as part of the domestic pigeon's environment.

Incidentally, creationists should note that Darwin never claimed evolution always resulted in new species. As he showed with his selective breeding examples, it produced new varieties too. Some of these have become so far removed from their wild ancestors that they rank as subspecies, like the domestic pigeon, Columba livia domestica

Although the radiation of domestic varieties is now well understood, the wild ancestors, the rock doves, have received far less attention until now. Now a paper by a team led by Germán Hernández-Alonso of the Center for Evolutionary Hologenomics, The Globe Institute, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, redresses that discrepancy by analysing the entire genomes of 65 historical rock doves that represent all currently recognized subspecies and span the species’ original geographic distribution. 3 of these specimens were from Charles Darwin's collection.

This works shows that rock doves have diversified into a number of subspecies across their range, stemming from a subspecies now restricted to a small coastal strip of Northwest Africa, C. livia gymnocyclus. One of these subspecies received a substantial ingression of genes from a related species, C. rupestris after it split from the West African population but before it became domesticated. The result is that C. livia gymnocyclus should now probably rank as a species in its own right, C. gymnocyclus.

First a little about the evolution of domestic pigeons:

Monday, 4 December 2023

Wonderful World - Ten Reasons to Like Spiders

Bottom left: European garden spider, Araneus diadematus

Bottom right: Banded Garden spider, Argiope trifasciata

Don't like spiders? Here are 10 reasons to change your mind

Back in the past, in what now seems like a lifetime ago, I managed the Emergency Operations Centre for my local Ambulance Service which was housed in a single-storey building in the grounds of the Church Hospital, Oxford. One of my nicknames was 'Spiderman' because of my fondness for spiders.

The roof space of this building was home to a population of 'house spider' or Tegenaria domestica, a good-sized one of which can be 4 inches or more across its outstretched legs. They frequently paid us a visit by coming through the light fittings or round the edges of the aircon unit.

The house spider is well-named, being one of those commensal species that, like barn swallows, can't exist without human habitation and so must have evolved after we became settled and built permanent dwellings.

Despite its large fangs, it is entirely harmless to humans, even if it does manage to pierce the skin - something I tried to impress on my staff, whose first response to one running across the floor was to stamp on it.

Despite this reassurance, one of my assistants was so arachnophobic she refused to enter the room until the spider was gone - although what she thought it would do to her was a mystery, so one of my tasks was to gently catch the spider in my hands and put it outside, whereupon I would deliver my famous (or maybe infamous) spider talk, in which I explained why spiders are such fascinating creatures - their very long evolutionary history from a common ancestor with scorpions; their multiple eyes (some for binocular vision and some for detecting movement) and above all their amazingly engineered webs.

Orb web spiders like the common garden spider, Araneus diadematus, make two sorts of silk - one to act as scaffolding and the radial threads of the web and sticky one to form the circular strands. Each thread of silk consists of multiple fine filaments that stretch very quickly to catch a flying insect without it bouncing off, then recoil slowly to avoid throwing the insect free. All this is controlled by the fine molecular structure and electrostatic bonds between the filaments. The result is a thread that, weight for weight, is stronger than steel.

One small spider that is common on walls and buildings in Oxford is the zebra spider, Salticus scenicus, a tiny black and white-striped spider, only a few millimeters long, that has amazing eyes. It is a hunting spider that preys on small insects, even some three times its size, by jumping on them. Its modus operandum is to crawl over the surface of walls and roofs and, when it sees its prey, it approaches slowly and when close enough, judges the distance perfectly and pounces. It will also jump across gaps, again with a perfectly judged jump, many times its own body length, rather like a human jumping the Grand Canyon from a standing start, but before it does so, it dabs the tip of its abdomen down to fix a 'safety line' of silk, just in case. To perform these feats, the zebra spider needs a high degree of visual acuity and binocular vison. The amazing thing about this spider is the way it overcomes the problem for visual acuity of such a small retina; it rapidly moves the retina up and down, effectively increasing its size.

The jump is accomplished, not by muscles in the legs, but by a sudden increase in haemocoelic blood pressure which straightens the front and back legs, so the spider always jumps with its legs extended.

I always hoped my spider talk would impress my staff enough to take an interest in spiders rather than seeing them as creepy-crawly things to be half-feared and killed simply for sharing the building with us. Alas, only one or two ever followed my example and picked them up to put them out of a window.

All that was by way of introduction to an article in The Conversation in which Leanda Denise Mason, an Associate Lecturer, Curtin University, Australia give her ten reasons to like spiders, or at least change your mind it you don't. Her article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Sunday, 3 December 2023

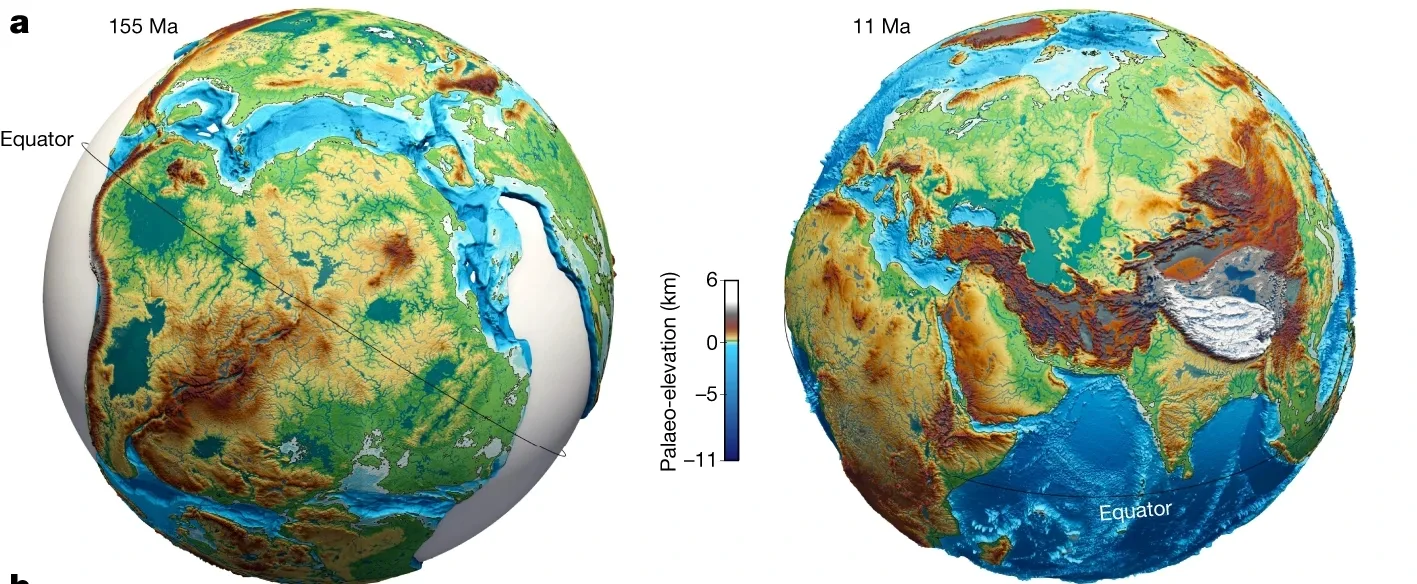

Creationism in Crisis - Scientists Show How a Dynamic And Changing Earth Influenced Evolution Over Millions of 'Pre-Creation' Years

Landscape dynamics determine the evolution of biodiversity on Earth - The University of Sydney

Again, it's the turn of geologists to refute creationism without even trying, like so many biologists do with their daily work.

Creationists insist that Earth is 'fine-tuned' for life; but as anyone who understands biology will know, life is 'fine-tuned' for Earth and the tuning process is called evolution by natural selection.

The observable fact that, over time, species have either evolved or gone extinct gives the lie to the 'fine-tuned for life' assertion because, if that were true, there would be no selection pressure for change and the fossil record would show no change.

In fact, the fossil record wouldn't exist as we know it because there would have been no evolution beyond the first free-living, single-celled prokaryote organisms because their environment would have been perfect for them.

Yet, as we know from daily observation, Earth is a changing and dynamic planet with periodic climate change, earthquakes and volcanoes caused by the slow process of plate tectonics, changing oxygen and carbon dioxide levels caused by the rise and fall of major ecosystems, and changing ocean currents caused by a number of different factors, not the least of which are climate change and plate tectonics. Then there are the cosmological changes caused by the Milankovitch cycles.

One of the consequences of this dynamic change is the way the Earth's surface is continually being recycled over geological time by erosion, transportation in water and sedimentation in ocean deposits as nutrients, then subduction and mountain-building and eventual resurfacing through volcanic activity. This gives changing levels of nutrients in the oceans that affect biodiversity both in the seas and on land.

This is the conclusion of a study by a team of geologists jointly led by Dr Tristan Salles of The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and Dr Laurent Husson of Université Grenoble-Alpes, Grenoble, France. They have shown an association between changes in nutrient levels due to sedimentation and mass extinctions. Their findings are published open access in Nature and are explained in a University of Sydney news release:

Creationism in Crisis - How America's East Coast Formed - 230 Million Years Before 'Creation Week'

Study Illuminates Formation of U.S. East Coast During Breakup of Supercontinent Pangea - SMU

It's not just the biologists who are incidentally refuting creationism with just about every peer-reviewed research paper; now the geologists are doing the same.

The problem for creationists is that their superstition has no basis in facts because it didn't happen and the record of how it did happen is in the evidence that science is revealing, so inevitably that evidence is going to refute the childish fairytale that creationists were taught by their parents who were taught it by their parents...

Take this piece of geological research into the formation of the East Coast of the USA, for example. It was carried out by scientists from the University of New Mexico, Southern Methodist University seismologist, Professor Maria Beatrice Magnani, and scientists from Northern Arizona University and the University of Southern California. It occurred in that long 'pre-Creation' history before creationists think Earth was magicked up out of nothing.

It is based on the knowledge that the East Coast of America formed when the supercontinent, Pangea, broke up some 230 million years before creationists think Earth existed.

Because it wasn't known about by the parochial and scientifically illiterate Bronze Age authors of their holy books, creationists are completely unaware of the way the present land-masses were formed on the breakup of Pangea, despite the abundant tectonic evidence in the form of mid-ocean ridges with their embedded record of multiple magnetic reversals over millions of years, subduction zones, earthquakes, volcanoes and uplift folds to form hills and mountains at tectonic plate margins.

Geology is a science about which my education has been somewhat lacking (I'm a biologist, physiologist and biochemist by training) but as I understand it, the edges of continents that were the site of the original rifts that opened up to form the oceans, particularly the Atlantic Oceans, will also show evidence of magma that would have welled up in the initial stages of the split.

In the case of the North American Atlantic coast, which is passive in this process because it is simply being pulled away from what is now Northwest Africa, and has not been subject to collisions with other plates, or any significant volcanic activity, these traces of magma are still to be found in the edges of the continental shelf beneath the ocean floor. Associated with the passive margin is a magnetic anomaly, The East Coast Magnetic Anomaly (ECMA), that runs parallel to the American East Coast.

My knowledge of the American East Coast is limited to two week vacation in Boston about 12 years ago, during which I tried bathing in Cape Cod Bay from a beach near South Wellfleet, to discover that I was standing barefoot on king crabs, either dead or alive (their remains littered the beach along Cape Cod), so I didn't spend long in the water - not that they were any threat to me but because they are not very pleasant to walk on.

As the Southern Methodist University news release explains:

Saturday, 2 December 2023

Malevolent Design News - How 'Intelligently Designed' Pathogens Use The Tactics Of A Burglar To Make Us Sick

Pathogens use force to breach immune defenses, study finds: IU News

Creationists trying to defend their magic creator god argue that it didn't create pathogenic parasites and instead blame it on 'Sin'. Sadly for them, however, one of their leading cult gurus, Michael J. Behe, has pulled that rug from underneath them by writing a book in which he used the supposedly irreducibly complex flagellum of a common pathogen, Escherichia coli (E. coli) to argue that it must have been intelligently designed, (so God did it!). Behe's book, 'Darwin’s Black Box' is constantly being cited as 'proof' that the reputedly omniscience, omnipotent creator god of the Bible and Qur'an is real and creates things.

So, let's go with their 'proof of God' argument and assume therefore that pathogens are the intentional design of their putative designer god and were designed for the function they perform - making us sick, while producing more copies of themselves to make others sick too.

Now a team of researchers have shown the lengths this alleged designer god has gone to to continue making us sick and suffer. The team, led by Professor Yan Yu, of the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Chemistry, Indian University, Bloomington, IN, USA have shown that the intracellular pathogens like Toxoplasma, tuberculosis, malaria and chlamydia don't use subtlety to gain entry into the cell, probably because this would provoke an immune response as our immune system, allegedly designed by the same intelligent designer to protect us from the pathogens it designed to harm us, tried to fight back. Instead, they use brute force to break into the cell and once inside use the same force to break into a cell vacuole where they are protected by the internal cell membranes.

How the research team which included Professor Yan Yu's colleagues from Indiana University with Thomas K. Gaetjens and Steven M. Abel of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, made this discovery is explained in an Indian University new release:

Creationism in Crisis - How Snakes Evolved To Meet The Demands Of Their Habitat And Food Sources

Snake skulls show how species adapt to prey - News Center - The University of Texas at Arlington

The ability to catch and consume prey species is a key aspect of evolutionary biology in carnivorous species, for obvious reasons, and so is a major source of divergence and radiation of species as each species become more and more specialised at catching different prey species.

An example of this was published recently in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution in which three researcher, led by Gregory G. Pandelis of the Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Research Center, Department of Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, Texas, USA with two colleagues from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, showed a correlation between prey species and skull morphology in dipsadine snakes.

How Science Works - Facing The Challenges of New Information

Creative Commons

Discovery of planet too big for its sun throws off solar system formation models | Penn State University

Theists embrace certainty at the expense of truth because it feels safe in an uncertain world in which truth is subordinate to opinion. Scientists embrace doubt because it leads them closer to the truth in a world full of wonder and begging to be understood, where truth is supreme and leads opinion wherever it may go.

In other words, religion is unreasonable certainty; science is reasonable uncertainty.

So, if there is one thing theists hate, it's being challenged with new information. It's not just scientific information that shows how far removed from reality their founding myths, such as those in the Bible, are, but information that shows, for example, that several of the 'epistles' attributed to Paul were forgeries trading on his name to give them added authority, or that the description of his 'conversion' on the road to Damascus was actually a description of a temporal lobe epileptic seizure and that his reason for being there didn't make any sense in the geo-political and legal context of the times.

So heavily invested are most devout theists that inconvenient facts like these are not considered reasons to change their minds; they are considered reasons to look for excuses to deny and dismiss the evidence. There is a vast and very lucrative industry, especially in the USA, which specialises in selling people 'reasons' to deny the science and believe the myths in the Bible, for instance. Remaining stoically ignorant of science is even considered virtuous in some parts of the world where religions still have a strangle hold.

Contrast that with science, where the most exciting news is that someone has discovered something that means we need to revise our thinking and change our minds. With science, when the facts change, the intellectually honest change their minds; with religion, when the facts change, they try to change the facts because the beliefs are sacred.

An example of how science welcomes and embraces new evidence is the news that cosmologists have probably discovered a massive planet orbiting a sun that is too small for such a large planet orbiting so close to it. This might not sound dramatic but if confirmed, it will demand a reassessment of how we think planetary systems form.

.jpg)