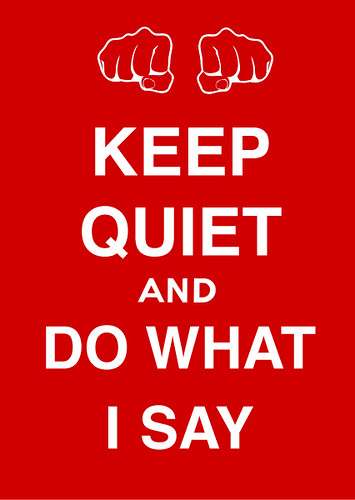

Here is C.S.Lewis on 'Faith', again from his 1952 book "Mere Christianity". It illustrates well the conceited vacuosity of his religious views and how his frankly annoying patronising style almost seems designed to gloss over it and to rely on the deferential social mores of his target audience. It oozes with 'niceness' and smugly reassuring self-satisfaction but actually says very little other than "believe what I say". I'm sorry it's so long but he probably had space to fill.

Here is C.S.Lewis on 'Faith', again from his 1952 book "Mere Christianity". It illustrates well the conceited vacuosity of his religious views and how his frankly annoying patronising style almost seems designed to gloss over it and to rely on the deferential social mores of his target audience. It oozes with 'niceness' and smugly reassuring self-satisfaction but actually says very little other than "believe what I say". I'm sorry it's so long but he probably had space to fill.I must talk in this chapter about what the Christians call Faith. Roughly speaking, the word Faith seems to be used by Christians in two senses or on two levels, and I will take them in turn. In the first sense it means simply Belief-accepting or regarding as true the doctrines of Christianity. That is fairly simple. But what does puzzle people-at least it used to puzzle me-is the fact that Christians regard faith in this sense as a virtue, I used to ask how on earth it can be a virtue-what is there moral or immoral about believing or not believing a set of statements? Obviously, I used to say, a sane man accepts or rejects any statement, not because he wants or does not want to, but because the evidence seems to him good or bad. If he were mistaken about the goodness or badness of the evidence that would not mean he was a bad man, but only that he was not very clever. And if he thought the evidence bad but tried to force himself to believe in spite of it, that would be merely stupid.Probably the key phrase in all this is, "But supposing a man's reason once decides that the weight of the evidence is for it".

Well, I think I still take that view. But what I did not see then- and a good many people do not see still-was this. I was assuming that if the human mind once accepts a thing as true it will automatically go on regarding it as true, until some real reason for reconsidering it turns up. In fact, I was assuming that the human mind is completely ruled by reason. But that is not so. For example, my reason is perfectly convinced by good evidence that anaesthetics do not smother me and that properly trained surgeons do not start operating until I am unconscious. But that does not alter the fact that when they have me down on the table and clap their horrible mask over my face, a mere childish panic begins inside me. I start thinking I am going to choke, and I am afraid they will start cutting me up before I am properly under. In other words, I lose my faith in anaesthetics. It is not reason that is taking away my faith: on the contrary, my faith is based on reason. It is my imagination and emotions. The battle is between faith and reason on one side and emotion and imagination on the other.

When you think of it you will see lots of instances of this. A man knows, on perfectly good evidence, that a pretty girl of his acquaintance is a liar and cannot keep a secret and ought not to be trusted; but when he finds himself with her his mind loses its faith in that bit of knowledge and he starts thinking, "Perhaps she'll be different this time," and once more makes a fool of himself and tells her something he ought not to have told her. His senses and emotions have destroyed his faith in what he really knows to be true. Or take a boy learning to swim. His reason knows perfectly well that an unsupported human body will not necessarily sink in water: he has seen dozens of people float and swim. But the whole question is whether he will be able to go on believing this when the instructor takes away his hand and leaves him unsupported in the water-or whether he will suddenly cease to believe it and get in a fright and go down.

Now just the same thing happens about Christianity. I am not asking anyone to accept Christianity if his best reasoning tells him that the weight of the evidence is against it. That is not the point at which Faith comes in. But supposing a man's reason once decides that the weight of the evidence is for it. I can tell that man what is going to happen to him in the next few weeks. There will come a moment when there is bad news, or he is in trouble, or is living among a lot of other people who do not believe it, and all at once his emotions will rise up and carry out a sort of blitz on his belief. Or else there will come a moment when he wants a woman, or wants to tell a lie, or feels very pleased with himself, or sees a chance of making a little money in some way that is not perfectly fair: some moment, in fact, at which it would be very convenient if Christianity were not true. And once again his wishes and desires will carry out a blitz. I am not talking of moments at which any real new reasons against Christianity turn up. Those have to be faced and that is a different matter. I am talking about moments where a mere mood rises up against it.

Now Faith, in the sense in which I am here using the word, is the art of holding on to things your reason has once accepted, in spite of your changing moods. For moods will change, whatever view your reason takes. I know that by experience. Now that I am a Christian I do have moods in which the whole thing looks very improbable: but when I was an atheist I had moods in which Christianity looked terribly probable. This rebellion of your moods against your real self is going to come anyway. That is why Faith is such a necessary virtue: unless you teach your moods "where they get off," you can never be either a sound Christian or even a sound atheist, but just a creature dithering to and fro, with its beliefs really dependent on the weather and the state of its digestion. Consequently one must train the habit of Faith.

Source; truthaccordingtoscripture.com

Nowhere in this book does he say what evidence convinced him. All his reasons for being a Christian are based on negatives and absent evidence; because he can't explain something using his rather tenuous grasp of science, or doesn't understand something, he declares it inexplicable, fills the gap with a god and deems it to be the god his parents told him about. To Lewis, it seems 'unknown' and 'unknowable' are synonyms. And of course this god is to be worshipped according the the rites and rituals of the church his was baptised into as an infant. Never a shred of definitive evidence is ever offered for this god nor any explanation of why, if he has to invoke a god, it follows that it must be the god of the Christian Bible.

Nowhere in this book does he say what evidence convinced him. All his reasons for being a Christian are based on negatives and absent evidence; because he can't explain something using his rather tenuous grasp of science, or doesn't understand something, he declares it inexplicable, fills the gap with a god and deems it to be the god his parents told him about. To Lewis, it seems 'unknown' and 'unknowable' are synonyms. And of course this god is to be worshipped according the the rites and rituals of the church his was baptised into as an infant. Never a shred of definitive evidence is ever offered for this god nor any explanation of why, if he has to invoke a god, it follows that it must be the god of the Christian Bible. How could the English have possibly got the wrong god? The idea is not even worth considering.

Nope. There must be a god and it must be Lewis' god because there are things Lewis can't understand, and it is virtuous to just have faith in that conclusion. And faith means never having to change your mind even when the evidence changes or you realise the 'evidence' wasn't what you thought it was.

To borrow a metaphor from Richard Dawkins, there is not sufficient evidence to have a firm belief either way on the cause of the mass extinction of dinosaurs. There is evidence that it could have been a large meteorite strike. It is plausible that it could have been a virus. It could possibly have been a catastrophic climate change caused by a super volcano. It is sheer arrogance to merely opt for one of those and then proclaim it a virtue to cling to that belief even when the evidence changes. Not only arrogant but vain, something Lewis regards as a sin. It can only come from the belief that one can merely 'know' the truth; that somehow something must be true because one believes it.

Faith, in the absence of definitive evidence, is not a virtue; it is the sin of vain arrogance writ large.

The mere fact that C.S.Lewis has opted to believe in the Christian god is sufficient reason for him to believe in it. None of this nonsensical subservience to reality and dependence on evidence for our hero. He comes from a class which not even the universe would dare to question. Reality is what he says it is and that's an end to the matter. He would not believe it if it were not just so.

And of course any reasonable plebeian hearing truth and wisdom dispensed by a brilliant Oxford don who even writes children's books, should accept it as good enough for him and marvel at the benevolence of such a nice man dispensing his knowledge so nicely, and with such simple words too.

What a wonderful example of a nice Christian.