Impression of South-eastern South Australia during the Pleistocene

(~500 thousand years ago)

(~500 thousand years ago)

Peter Schouten

Archaeologists have re-assesses the fossils of giant kangaroos that lived in the Pleistocene along with other megafauna such as giant goannas (an Australian lizard) or Megalania, Varanus priscus, that grew to 4 meters (about 13 feet) long and went extinct about 40,000 years ago along with much of the megafauna. One of these kangaroos, the short-faced kangaroo Procoptodon goliah grew to three metres (9.5 feet) and probably weighed over 250 kilograms (about 550 lbs).

Why these large animals went extinct and what part if any the arrival of Homo sapiens played any part in it is a matter of debate, but what is not a matter for debate is whether or not they existed and when. Their discovery is explained by Isaac A. R. Kerr, a Research Assistant in the Palaeontology Laboratory, Flinders University, Australia in an open access article in The Conversation. His article is reprinted here, reformatted for stylistic consistency, under a Creative Commons license:

We found three new species of extinct giant kangaroo – and we don’t know why they died out when their cousins survived

Artist’s impression of the prehistoric landscape and creatures that Protemnodon would have walked among.

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Flinders UniversityPeter Schouten

For millions of years, giant animals or megafauna roamed the lands that are now Australia and New Guinea. Many were like much larger versions of modern animals.

There was a four-metre goanna called Megalania (Varanus priscus), for example, which likely ambushed its prey. This beast disappeared by around 40,000 years ago along with almost all the other megafauna aside from remnants such as the red kangaroo and the saltwater crocodile.

Some of the now-vanished kangaroo species were quite massive. The short-faced kangaroo Procoptodon goliah grew as tall as three metres and may have weighed more than 250 kilograms.

There was another genus of extinct kangaroos, Protemnodon, which were more like the grey and red roos we know today, but little has been known about their lives. In a new study, my colleagues and I describe three new species of these vanished marsupials – and shed some light on where they lived and how they got around.

A 150-year puzzle

The first species of Protemnodon were described in 1874 by the British naturalist Richard Owen. As was standard at the time, Owen focused chiefly on fossil teeth. Seeing minor differences between teeth from different fragmentary specimens, he described six species of Protemnodon.

However, Owen’s species have not stood the test of time. Our study agrees with only one of his species — Protemnodon anak. The first specimen of P. anak to be described, called the holotype, still resides in the Natural History Museum in London.

Fossils of individual Protemnodon bones are not uncommon, but more complete skeletons are rare. This has hampered palaeontologists’ efforts to study the creatures.

The question of how many species there were, and how to tell them apart, has not been fully answered. This has made it hard to say how the species differed in their size, geographic range, movement and adaptations to their natural environments.

I set out to solve this problem in my PhD project. With fellow PhD student Jacob van Zoelen, I visited the collections of 14 museums in four countries to gather data.

We have now seen just about every piece of Protemnodon that exists above ground, photographing, scanning, measuring, comparing and describing more than 800 specimens collected from all over Australia and New Guinea.

Finding the key

Among all this study, the key to the Protemnodon problem turned out to be buried in the dry bed of Lake Callabonna in northeastern South Australia. Three expeditions to Lake Callabonna from 2013 to 2019 found a megafaunal boneyard: complete skeletons of giant kangaroos, giant wombats, and Genyornis newtoni, a 250kg flightless bird, were scattered among the remains of hundreds of Diprotodon optatum, a rhino-sized marsupial herbivore. This lake likely preserves animals that died while searching for water during prolonged drought.

I accompanied the 2018 trip, which returned with all manner of amazing articulated fossils. These fossils allowed me, then a PhD student in my first year, to begin the process of picking apart the identities of the kangaroos.

Two of Richard Owen’s species, Protemnodon brehus and Protemnodon roechus, were only known from their teeth, which were extremely similar. We unearthed and compared several kangaroos with teeth that could have belonged to either of Owen’s species, but the skeletons didn’t match.

By the international rules of species naming, this meant we had to describe two new species. These are Protemnodon viator from central Australia and Protemnodon mamkurra from southern Australia.

Big kangaroos with big differences

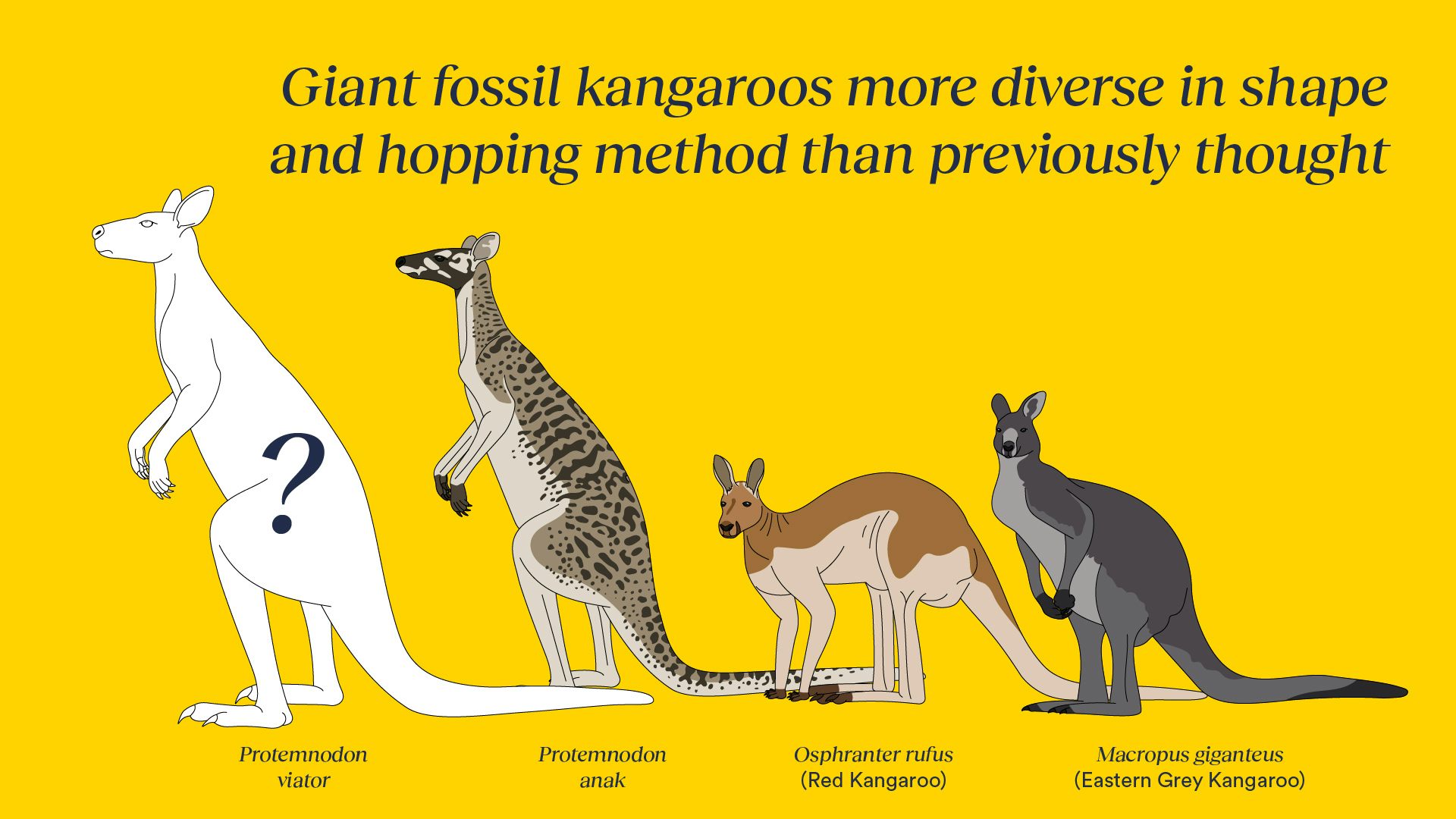

Our study reviews all species of Protemnodon, finding surprising differences. We concluded that there are seven species in the genus, adapted to live in very different environments and even hopping in different ways. This level of variation is unusual within a single genus of kangaroo.

The newly described species Protemnodon viator was bigger than its relative P. anak, and much bigger than the red and Eastern grey kangaroos we know today.

Traci Klarenbeek

Protemnodon viator was well-adapted to its arid central Australian habitat, living in similar areas to the red kangaroos of today. Protemnodon viator was much bigger, however, weighing up to 170 kg, about twice as much as the largest male red kangaroos.

Our study suggests two or three species of Protemnodon may have been mostly quadrupedal, moving something like a quokka or potoroo – bounding on four legs at times, and hopping on two legs at others.

The newly described Protemnodon mamkurra is likely one of these. A large but thick-boned and robust kangaroo, it was probably fairly slow-moving and inefficient. It may have hopped only rarely, perhaps just when startled.

The best fossils of this species come from southeastern South Australia, on the land of the Boandik people. The species name, mamkurra, was chosen by Boandik elders and language experts in the Burrandies Corporation. It means “great kangaroo” in Bunganditj language.

The third of our newly described species is Protemnodon dawsonae, a woodland-dwelling kangaroo from eastern Australia and the probable ancestor of P. viator and P. mamkurra. It is named for kangaroo palaeontologist Lyndall Dawson.

By about 40,000 years ago, despite their many differences, all Protemnodon were extinct on mainland Australia. We don’t yet know why they died out when similar animals such as wallaroos and grey kangaroos survived – but our study may open the door for further Protemnodon research that will find out more about how they lived and why they died.

Isaac A. R. Kerr, Research Assistant at Flinders University Palaeontology Laboratory, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AbstractWith so much of the known history of life on Earth occurring in the 99.99% of it that came before creationism's legendary 'Creation Week' it's hardly surprising that we keep finding fossils from the long pre-'Creation' history, but refuting childish creationist superstitions was never part of the plan for these palaeontologists who were more interested in the correct taxonomy of the species and just incidentally refuted creationism again.

Species of the kangaroo genus Protemnodon were common members of late Cenozoic communities across Australia and New Guinea until their extinction in the late Pleistocene. However, since the genus was first raised 150 years ago, it has proven difficult to diagnose, as have the species allocated to it. This is due primarily to the incompleteness of the type material and a heavy reliance on cheek tooth size and slight variations in premolar form. Along with the rare association between cranial and postcranial material, this has hampered understanding of the palaeobiology of these large-bodied kangaroos. Here we review and re-diagnose Protemnodon, recognising a total of seven species and providing a hypothesis of species interrelationships. The following new synonymies are made: Protemnodon chinchillaensis is synonymised with P. otibandus and P. hopei with P. tumbuna. The following are considered nomina dubia: Protemnodon brehus, P. roechus, P. mimas, P. antaeus, and P. devisi. We reveal that the morphology of the cheek dentition is not as consistently useful for differentiating species of Protemnodon as features of the cranium and postcranial skeleton. As a whole, the species share anatomical features that reflect stability and power in the limb joints, yet they differ in body proportions, and axial and limb morphology. This we interpret as showing locomotory adaptations to different habitats. Of the three Pliocene species, Protemnodon snewini is interpreted as a medium- to high-geared hopper, suggesting proficiency in more open environments, whereas P. dawsonae sp. nov. we infer to have been a medium-geared inhabitant of eastern Australian forests and woodlands. Protemnodon otibandus, with a range extending through the woodlands and forests of eastern Australia into the rainforests of eastern New Guinea, displays adaptations to slower hopping. Its Pleistocene descendant, P. tumbuna, is convergent on the morphology of modern New Guinea forest wallabies, and was likely facultatively quadrupedal. Of the three Australian Pleistocene species, the long-necked P. anak is hypothesised to have been a large, medium-geared, eastern Australian species, and P. mamkurra sp. nov. a robust, low-geared resident of well-wooded southern Australia habitats. By contrast, P. viator sp. nov. was larger but more gracile, suggested to be a medium- to high-geared species convergent in some traits on large extant kangaroos. This and a wide inland distribution point to adeptness in open, arid environments. Protemnodon mamkurra sp. nov. and P. viator sp. nov. occupy the morphospace previously occupied by P. roechus and P. brehus. Overall, the species of Protemnodon exhibit a degree of ecomorphological variation suggestive of a broader array of ecological adaptations than hitherto envisioned.

Kerr, Isaac A.R; Camens, Aaron B.; Van Zoelen, Jacob D.; Worthy, Trevor H. & Prideaux, Gavin J. Systematics and palaeobiology of kangaroos of the late Cenozoic genus Protemnodon (Marsupialia, Macropodidae) Megataxa (2024) 11(1) 1-261; DOI: 10.11646/MEGATAXA.11.1.1

Copyright: © 024 The authors.

Published by Magnolia Press. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

How did you come to be here, now? This books takes you from the Big Bang to the evolution of modern humans and the history of human cultures, showing that science is an adventure of discovery and a source of limitless wonder, giving us richer and more rewarding appreciation of the phenomenal privilege of merely being alive and able to begin to understand it all.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.