Archaeological excavation work in June at the Roc de les Orenetes site (Queralbs, Ripollès).

IPHES-CERCA

Around the time creationists claim Earth was undergoing a global flood — a mass genocide by drowning, supposedly enacted by a deity - a belief based solely on the origin myths of a Bronze Age Middle Eastern pastoralist tribe — people in the Pyrenees were engaged in violent conflict, using bows and arrows. Unlike biblical mythology, this insight is grounded in tangible evidence: a human rib bone with a flint arrowhead still embedded in it. Remarkably, the injury had healed before the individual died, suggesting they survived the attack for some time. The rib was found in a mass grave at Roc de les Orenetes (Queralbs, Girona), alongside the remains of several others, many of whom showed signs of trauma from blunt or sharp weapons, particularly to the head and upper body.

The timing of this violence — dated to between 4,100 and 4,500 years ago — is problematic for biblical literalists. If the Genesis flood had truly occurred as described, these remains should either have been destroyed or buried beneath a thick layer of flood-deposited silt, mixed with the remains of animals and plants not native to the region. Alternatively, one must believe that just a few years after a supposed global reset that reduced humanity to eight survivors, their descendants had multiplied sufficiently to form warring groups in the mountains of what is now northern Spain.

And yet, these individuals show no sign of having heard of Noah, his family, or the god who allegedly saved them. There’s no indication of the monotheistic religion supposedly preserved aboard the ark. If the flood story were true, the moral lesson it was intended to deliver seems to have been forgotten almost immediately, everywhere except among a small group in the Canaanite hills.

This discovery joins a growing list of archaeological findings that contradict the flood narrative. Far from showing a global cataclysm, the archaeological record reveals continuous human habitation before, during, and after the time the flood is supposed to have occurred—with no signs of interruption, no replacement by a Near Eastern culture, and no characteristic flood-deposited sediment layer.

It’s almost as if the global flood never happened. Not only is there no geological or archaeological evidence supporting it, but what evidence we do have consistently contradicts it. This find from the Pyrenees is yet another example.

What information do you have about Bronze Age People in Northern Spain? Bronze Age people in northern Spain—especially in regions like the Pyrenees, Cantabria, Asturias, and Galicia—left behind a rich archaeological record that reveals a complex picture of cultural development, trade, warfare, and continuity from earlier Neolithic traditions. Here's an overview of what is known:The discovery was published in August 2024 in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, and announced in a news release by the Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social.

Chronology and Cultural Context

- Timeframe: The Bronze Age in the Iberian Peninsula generally spans from ~2200 BCE to ~850 BCE, but regional variations exist.

- Northern Spain: The region did not follow the same trajectory as southeastern Iberia, where more complex urbanised cultures like El Argar emerged. Instead, northern communities maintained more localised, often conservative lifeways that transitioned slowly from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age.

Settlement and Lifestyle

- Small, dispersed settlements: Typically located on hills or in defensible areas like caves or rock shelters. The Pyrenees, for example, offered natural fortifications.

- Subsistence: Mixed agriculture and livestock farming (sheep, goats, cattle, pigs). Hunting and gathering supplemented diets.

- Architecture: Simple round or oval dwellings with stone foundations and wattle-and-daub walls. Fortified hilltop sites (castros) began appearing later in the period.

Violence and Warfare

- Evidence of conflict: Increasing evidence, such as the mass grave at Roc de les Orenetes, suggests intergroup violence during the Late Neolithic to Bronze Age transition (~2500–1500 BCE).

- Weapons: Flint arrowheads, bronze daggers and axes, and sling stones have been found, indicating a capacity for both personal and group-level violence.

Tools and Technology

- Metallurgy: Bronze tools and weapons became more widespread by the Middle Bronze Age (~1500 BCE), although northern Iberia lagged behind the more advanced metallurgy seen in El Argar (southeast Iberia).

- Ceramics: Hand-made pottery with geometric decorations. Some influence from Bell Beaker culture is evident in earlier phases.

Cultural Influences and Trade

- Bell Beaker culture (~2600–1800 BCE): Present across Iberia, including northern regions. Known for distinctive pottery, copper tools, and burial practices. Their arrival may have introduced metallurgy and social stratification.

- Trade networks: Though more limited than in southeastern Spain, there is evidence of long-distance trade—metal objects and exotic materials like amber made their way into northern Iberia.

Burial Practices

- Varied forms: Including megalithic tombs (dolmens), cave burials, and later tumulus (barrow) graves. Collective burials were common.

- Grave goods: Some burials included bronze tools, weapons, and ornaments, indicating social differentiation.

Genetics and Population

- Recent ancient DNA studies show a genetic turnover in the Iberian Peninsula during the Bronze Age, linked to migrations from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe via Central Europe. However, this impact was less pronounced in the northwest and north compared to central and southeastern Iberia.

- The Yamnaya-related steppe ancestry is detectable but diluted in northern Iberia, suggesting a degree of cultural and genetic continuity from earlier Neolithic populations.

Key Sites

- Roc de les Orenetes (Queralbs, Girona): Late Neolithic / Early Bronze Age cave site with evidence of interpersonal violence, including the recently discovered mass grave with healed and fatal trauma.

- Dolmens of the Basque Country and Cantabria: Used throughout the Neolithic and into the Bronze Age.

- La Campa Torres (Asturias): Proto-urban fortified site occupied from the Late Bronze Age into the Iron Age.

Summary

Bronze Age societies in northern Spain were:

- Generally less hierarchical and urbanised than those in southern Iberia.

- Agriculturally based, with emerging metalworking.

- Culturally conservative, retaining Neolithic elements.

- Affected by, but not completely transformed by, continental influences like Bell Beaker and Steppe migrations.

- Capable of significant social violence, as shown by recent archaeological finds.

Arrowhead embedded in a human rib reveals prehistoric violence in the Pyrenees over 4,000 years ago

An exceptional case of interpersonal violence has been identified in a prehistoric burial site at 1,800 metres above sea level in the Catalan Pyrenees. A flint arrowhead was found embedded in a human rib, showing clear signs of survival after the impact

A flint arrowhead embedded in a human rib, found at the Roc de les Orenetes site (Queralbs, Girona, northeastern Spain), offers rare direct evidence of interpersonal violence in the Pyrenees more than 4,000 years ago. The arrow was shot from behind and remained lodged in the bone, which shows signs of healing — indicating the person survived for some time after the injury.

The discovery was made during recent excavations at this high-altitude collective burial site, led since 2019 by Dr. Carlos Tornero of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social (IPHES-CERCA). The osteological study is led by Dr. Miguel Ángel Moreno (University of Edinburgh).

The projectile will now undergo detailed analysis using X-ray microtomography at the National Research Centre on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, followed by chemical and genomic studies in Barcelona and the United States.

The Roc de les Orenetes cave is one of the few high-mountain funerary sites in Europe with such a large and well-preserved human assemblage, offering unique insight into the lives, deaths, and social dynamics (including episodes of violence) of Bronze Age mountain communities.

Publication:

AbstractDiscoveries such as the mass grave at Roc de les Orenetes in the Pyrenees expose the profound disconnect between the claims of biblical literalism and the physical evidence left by prehistoric peoples. According to a literal reading of the Book of Genesis, a global flood wiped out all of humanity — except for eight survivors — around 4,300 years ago. Yet here we find unequivocal evidence of well-established communities living, fighting, and dying in northern Spain during precisely the time this supposed global cataclysm was meant to have occurred.

Objectives

To test a hypothesis on interpersonal violence events during the transition between Chalcolithic and Bronze Age in the Eastern Pyrenees, to contextualize it in Western Europe during that period, and to assess if these marks can be differentiated from secondary funerary treatment.

Materials and Methods

Metric and non-metric methods were used to estimate the age-at-death and sex of the skeletal remains. Perimortem injuries were observed and analyzed with stereomicroscopy and confocal microscopy.

Results

Among the minimum of 51 individuals documented, at least six people showed evidence of perimortem trauma. All age groups and both sexes are represented in the skeletal sample, but those with violent injuries are predominantly males. Twenty-six bones had 49 injuries, 48 of which involved sharp force trauma on postcranial elements, and one example of blunt force trauma on a cranium. The wounds were mostly located on the upper extremities and ribs, anterior and posterior. Several antemortem lesions were also documented in the assemblage.

Discussion

The perimortem lesions, together with direct dating, suggest that more than one episode of interpersonal violence took place between the Late Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age in northeastern Spain. The features of the sharp force trauma indicate that different weapons were used, including sharp metal objects and lithic projectiles. The Roc de les Orenetes assemblage represents a scenario of recurrent lethal confrontation in a high mountain geographic context, representing the evidence of inferred interpersonal violence located at the highest altitude settings in the Pyrenees, at 1836 meters above sea level.

1 INTRODUCTION

Violence has been part of human behavior since the Paleolithic (Churchill et al., 2009; Knüsel et al., 2023; Sala et al., 2015; Zollikofer et al., 2002), but from the Neolithic period onwards an important change is observed in Europe involving a general increase in violent behavior (Guilaine & Zammit, 2005; Schulting & Fibiger, 2012; Smith, 2017). This is associated with the large number of social, economic, demographic, technological, and cultural changes that occurred at the beginning of this period (Larsen, 2006; Whittle, 1996), and is also partly a function of increasingly better preservation of human remains as a result of more ritualized funerary practices, especially collective burials.

Since the Neolithic and continuing into the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age, there are numerous cases of inter-group confrontations in the archeological record (Alt et al., 2020; Brinker et al., 2016; Golitko & Keeley, 2007; Janković et al., 2021; Jiménez-Brobeil et al., 2009.1; Konopka et al., 2016.1; Meyer et al., 2015.1). The remains of the victims were buried in both open-air mass graves and placed in monumental structures or caves as part of successive collective burials. The latter is the case at Roc de les Orenetes (Queralbs, Girona), a cave where the skeletal remains of multiple individuals have been found, with some of their bones displaying perimortem blunt and, especially, sharp force trauma. The first step to be taken involves identification of this type of injury as being caused by violent confrontations.

Human funerary practices are part of the symbolic sphere and beliefs of societies, which is why they are highly diverse and complex. It is possible to find funerary practices that include the manipulation of human remains either before or after burial (Belcastro et al., 2021.1; Crozier, 2016.2; Duday, 2009.2; Erdal, 2015.2; Fowler, 2010; Geber et al., 2017.1; Mariotti et al., 2020.1; Robb et al., 2015.3; Santana et al., 2012.1, 2015.4; Simmons et al., 2007.1; Wallduck & Bello, 2016.3). The processing of the bodies for consumption in episodes of cannibalism is another scenario in which blows and cut marks on the bones are documented (Andrews & Fernández-Jalvo, 2003; Bello et al., 2015.5, 2016.4; Boulestin & Coupey, 2015.6; Cáceres et al., 2007.2; Marginedas et al., 2022; Nicolosi et al., 2023.1; Rougier et al., 2016.5; Sala & Conard, 2016.6; Saladié et al., 2012.2; Saladié & Rodríguez-Hidalgo, 2017.2; Santana et al., 2019; Turner & Turner, 1999; White, 1992). Identifying the etiology of perimortem injuries as a result of a specific practice can radically change the interpretation of a given burial. For this reason, one of the main objectives of the present work is to carry out an in-depth description and analysis of the perimortem injuries documented at the Roc de les Orenetes site. We discuss here why their morphological features and location on the skeleton are consistent with an episode of interpersonal violence but not with food processing or funerary practices.

Evidence of violence in skeletal remains, such as antemortem and perimortem wounds, often related to the manner of death of individuals. This informs us about the hazards of living in prehistoric communities. We should not think that Europe between the Neolithic and Bronze Age was immersed in a constant atmosphere of violence, but rather, sporadic confrontations were generally on a small or medium scale. Aims of such violence rarely sought to annihilate an opposing group, and the majority involved non-lethal skirmishes over social, resource-based, or territorial disputes (Fibiger et al., 2023.2; Golitko & Keeley, 2007; Larsen, 2006; Schulting & Fibiger, 2012; Schulting & Wysocki, 2005.1; Smith, 2017; Soriano et al., 2015.7; Wild et al., 2004).

Signs of violence on the skeleton not only inform us about past confrontations, but also illuminate about the circumstances surrounding the death of individuals, such as the type of weapons used, the direction of the attacks, and the demographic profile of the victims. This can provide information on whether it was an intergroup fight or a one-way massacre. It makes it possible to discern whether we are dealing with the victims of an assault or execution, or with those killed in interpersonal or intergroup confrontations. The transition between the Late Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age in Western Europe involved a broad spectrum of social, economic and technological transformations, and the inevitable disputes that these large-scale reformulations brought with them (Blanco-González et al., 2018; Brinker et al., 2016; Guilaine & Zammit, 2005; Harding, 2007.3; Janković et al., 2021; Smith, 2017; Soriano, 2013). Here, a taphonomic analysis of the marks of violence documented at the Roc de les Orenetes site provides a detailed reconstruction and interpretation of the circumstances surrounding the deaths of these individuals. This study, together with the first direct dating carried out on the buried individuals, provides a chronological and geographical contextualization of this collective burial, located in the high mountains of the Eastern Pyrenees.

2 THE SITE OF ROC DE LES ORENETES

Roc de les Orenetes is a karstic cave located in the Eastern Pyrenees in the municipality of Queralbs (Girona, Spain), at an altitude of 1836 m above sea level (Figure 1). The cave consists of a main gallery 17 m long, 1–4 m wide, and an average height of 1.5 m. The entrance is a small and narrow mouth oriented southwest, which provides access directly to this chamber. A secondary and smaller access point to the cave is possible through an inferior gallery, located two meters below, although it is today inaccessible.

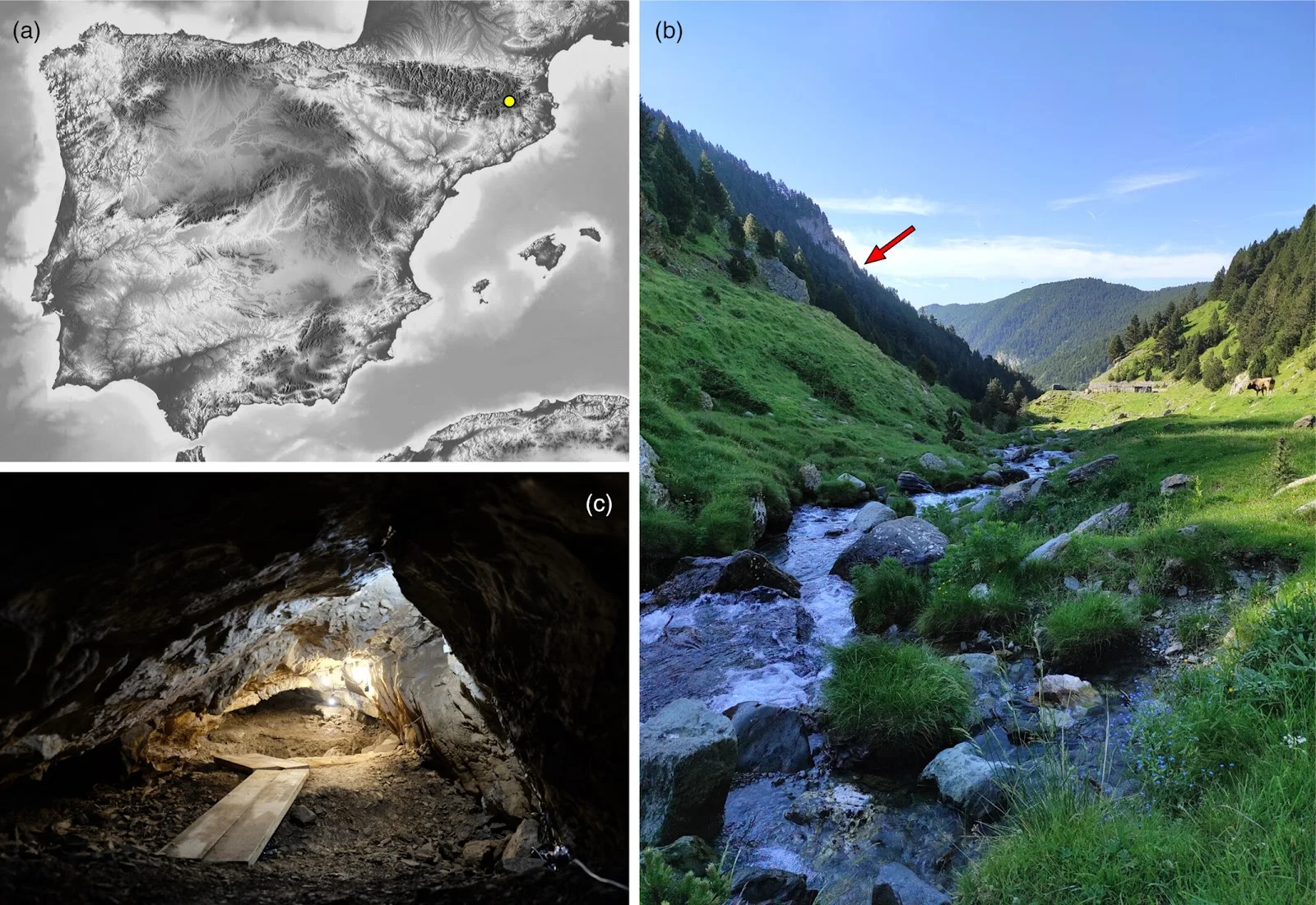

The site was discovered by a local resident in 1969, and in 1972–1973 two archeological rescue projects were carried out. As a result of this fieldwork, more than a thousand human bones were recovered, along with faunal remains, ceramic fragments, and bronze ornamental objects (Carbonell et al., 1985; Soriano, 2013; Toledo, 1990; Toledo & Pons, 1982). It was confirmed that the cave was used as a collective burial chamber, and it was chrono-culturally consistent with the Bronze Age by the metallic elements found. No further investigations were carried out in the cave until its reopening in 2019 as part of a new research project (CLT009/18/00048) (Ramírez-Pedraza et al., 2020.2), which continues today (CLT009/22/000042) (Ramírez-Pedraza et al., 2022.1). New fieldwork began in 2019 with a 2×1 m test pit, which has been expanded with each excavation in successive years. The cave has not yet been completely excavated. (a) Location of the Roc de les Orenetes site on the Iberian Peninsula; (b) view of the cave location (rocky area on the red arrow) from the Tosa River, near the Font de l'Home Mort; and (c) interior of the cave seen from the entrance).

(a) Location of the Roc de les Orenetes site on the Iberian Peninsula; (b) view of the cave location (rocky area on the red arrow) from the Tosa River, near the Font de l'Home Mort; and (c) interior of the cave seen from the entrance).

At the moment, a single archeological layer has been documented, forming the upper 20 cm of the vertical stratigraphic profile. Below it, a sterile layer follows, clearly differentiated from the archeological one in both texture and sedimentary composition, and the natural base of the cave has not yet been found. No stratigraphic differentiation is observed within the archeological layer, which presents a high density of mainly highly commingled human bones (Supporting Information, Figure S1). The total recovery of skeletal remains was ensured by water-sieving all sediment that came from this layer. The archeological remains found suggest that the cave was mainly used for funerary purposes and no other activities have been documented at the site to date.

In the most recent excavations, some faunal remains, ceramic fragments, small charcoal concretations and five tanged and barbed projectile points have been recovered at the site. The projectiles were found both on surface and in stratigraphic context. Four of them are made of chert and one of bone.

The first set of 14C dates from the site was carried out on six human bones bearing anthropogenic marks of violence (Table 1, Figure 2), involving of one cranium, four humeri, and two radii. These samples came from both the 1972 to 1973 excavations and the 2019–2021 field seasons. The processing of the dates with Bayesian modeling made it possible to establish that the episodes of interpersonal violence occurred over 400 years, from 4500 to 4100 years cal. BP (Figure 2) (2550–2150 cal. BC). These dates are culturally framed between the Late Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age, which in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula (today, Catalonia) spans c. 4700–4250 and c. 4250–3750 years cal. BP (Clop & Majó, 2017.3; Oms et al., 2016.7; Soriano, 2013, 2016.8). However, the bronze ornaments indicate a funerary use of the cave into the Bronze Age (Soriano,2013). This successive use of the caves as a funerary space over a long period is very frequent in collective burials from the Neolithic onwards (Aranda Jiménez et al., 2020.3; Bosch et al., 2016.9; Lorrio & Montero, 2004.1; Moreno-Ibáñez et al., 2022.2).FIGURE 3

(a) Cranium Ro73-5986 from Roc de les Orenetes showing a blunt force trauma (BFT) on the right temporal bone and (b) close view of the fracture.

FIGURE 4

Humeri and clavicle showing chop marks. (a) Left humerus Ro73-4711.1; (b) left clavicle Ro19-1015; (c) left humerus Ro21-3469; and (d) left humerus Ro73-6363.The arrows indicate the direction of the blows.

FIGURE 5

Humeri with chop marks. (a) Right humerus fragment Ro21-3375 (the yellow arrow indicates the heavy SFT that penetrated the medullary cavity); (b) right humerus Ro20-1902 with multiple chop marks; and (c) fragment of right humerus Ro20-2085. The arrows indicate the direction of the blows.

FIGURE 6

Forearm elements with chop marks. (a) Right radius Ro20-1960; (b) subadult left radius Ro20-2126; (c) left proximal phalanx Ro20-1909; and (d) juvenile right radius Ro21-3453 showing three chop marks, with the heaviest transecting the forearm (yellow arrow). The arrows indicate the direction of the blows.

FIGURE 7

Ribs with chop marks. (a) Left rib Ro21-3246; (b) right rib Ro73-6677/6595 with three stabbing chop marks, two of them contiguous, between the neck and the angle of the rib, and one towards the midshaft; (c) left rib fragment Ro20-2034 with multiple chop marks; (d) right rib Ro21-3259; and (e) right rib Ro21-3324. The arrows indicate the direction of the blows.

FIGURE 8

Elements of the lower appendicular skeleton (and one vertebra) showing chop marks. (a) right femur Ro20-1606; (b) left tibia Ro21-3526; and (c) lumbar vertebra (L5) Ro21-3479.

FIGURE 9

Bones with slice marks. (a) Left scapula Ro73-6873; (b) left rib fragment Ro20-1762 showing a slice mark on the inner surface; (c) left humerus Ro73-6325 with a longitudinal slice or scrape; (d) right rib Ro73-6442; (e) subadult left ulna Ro21-3497; and (f) right rib fragment Ro73-6520 with a longitudinal and wide scrape mark. The arrows indicate the direction of the cuts.

FIGURE 10

Antemortem cranial trauma. (a) Cranium Ro73-5878.1, adult female, 30–40 years of age at death; (b) cranium Ro73-5985, adult male, 30–40 years of age at death; (c) cranium Ro73-3692, adult male, 35–45 years of age at death; (d) cranium Ro73-6236, young adult male, 20–30 years of age at death; (e) cranium Ro73-6045, adult male, 40–50 years of age at death.

FIGURE 11

Left ulna fragment Ro73-7291 with evidence of amputation and remodeling of transected end. The radiographic image shows complete healing of the bone tissue.

FIGURE 12

Arrowheads from Roc de les Orenetes. (a–d) Chert barbed and tanged points. (e) Bone barbed and tanged point. Points Ro19-1430 (a) and Ro19-1431 (b) showed severe post-depositional effects that did not allow microscopic analysis. (c) Point Ro21-2840 shows a distal impact fracture. (d) Recycled point with persistence of thermal patina in the central area of both faces. (e) Bone arrowhead; scanning of its surface with the confocal microscope (e1), and detail of the Spin-Off type impact fracture, consisting of an oblique transverse fracture from which longitudinal removals depart in the distal zone (e2).

FIGURE 13

Use-wear analysis of arrowheads Ro21-2840 and Ro20-1718. Point Ro21-2840 showed (a, b) a bifacial Spin-Off fracture related to a projectile impact, (c) rounding of the barb with an intense bright-spot with MLIT superimposed, (d) partially detached bright-spot of hafting with MLIT superimposed, and (e) distal MLIT associated with the impact. The point Ro20-1718 showed (f-g) polishing on the distal ridges on both faces of the point associated with rotational movement, and (g) a distal fracture with cracking that removed part of the previous polishing.

FIGURE 14

Pattern of skeletal distribution of antemortem and perimortem trauma.Moreno-Ibáñez, M. Á., Saladié, P., Ramírez-Pedraza, I., Díez-Canseco, C., Fernández-Marchena, J. L., Soriano, E., Carbonell, E., & Tornero, C. (2024).

Death in the high mountains: Evidence of interpersonal violence during Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age at Roc de les Orenetes (Eastern Pyrenees, Spain).

American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 184(1), e24909. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24909.

Copyright: ©2025 The authors.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Far from being wiped clean by floodwaters or buried beneath thick, chaotic sediment layers filled with the remains of animals and plants from distant regions, these remains are undisturbed in their archaeological context. They show continuity of occupation, local cultural traditions, and social dynamics — none of which fits the narrative of a planet-spanning reset. The individuals in the Roc de les Orenetes mass grave not only lived through violent conflict, but one of them survived a serious arrow wound long enough for it to heal. Their lives, deaths, and burials represent an entirely normal progression of human activity in the region—utterly at odds with the idea of a recent global extinction event.

If the biblical flood had occurred, we should find a global, uniform layer of flood-deposited sediment, with an abrupt break in human cultural continuity, followed by a single point of repopulation radiating from the Middle East. Instead, the archaeological record tells a different story: uninterrupted human habitation across multiple continents, with regional variation and local development continuing without any sign of a population bottleneck or global trauma.

That such evidence exists — and continues to accumulate — is not just inconvenient for young-Earth creationism. It’s fatal to it.

Advertisement

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

How did you come to be here, now? This books takes you from the Big Bang to the evolution of modern humans and the history of human cultures, showing that science is an adventure of discovery and a source of limitless wonder, giving us richer and more rewarding appreciation of the phenomenal privilege of merely being alive and able to begin to understand it all.

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

All titles available in paperback, hardcover, ebook for Kindle and audio format.

Prices correct at time of publication. for current prices.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.