Fig. 3: Behavior-specific and situation-specific global everyday norms.

A A color-coded matrix illustrating the global appropriateness ratings (averaged over 71 societies) of fifteen behaviors in each of ten situations. B Scatter plot illustrating appropriateness ratings of fifteen specific behaviors aggregated across various situations (centered on the mean across behaviors) and their strong negative association with the sum of behavior-specific concerns about vulgarity and inconsiderateness. The index ‘b’ indicates that measures refer to behaviors. C Scatter plot illustrating appropriateness ratings of 15 behaviors in ten specific situations (n = 150 situated behaviors, centered on the mean across situations for each behavior) and their strong negative association with the sum of situation-specific concerns about inconsiderateness and lacking sense. The index ‘xb’ indicates that measures refer to situated behaviors. Gray shading indicates 95% confidence intervals.

An important new study, led by researchers from Mälardalen University (MDU, Sweden) and the Institute for Futures Studies (IFFS), in collaboration with over 100 researchers worldwide, sheds light on how social norms vary across cultures yet share fundamental commonalities.

As someone who has travelled extensively in Western and Eastern Europe, North Africa, Kuwait, Oman, India, and the USA, I can personally attest to cultural differences that extend far beyond language. Everyday activities such as driving, for instance, reveal how deeply embedded these norms are. It can take several days to adapt to local expectations, and even then, you may still be greeted with an indignant horn or an icy stare for something entirely unremarkable in your own country.

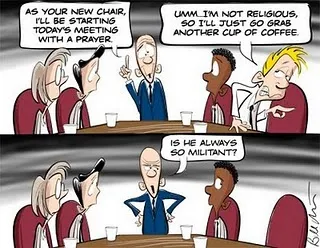

Creationists often claim that morality is a divine gift — that without their god, we would have no concept of right and wrong. As an atheist, I grow weary of being told that I “hate God” because I supposedly “want to sin”, or that I lack a moral compass. Such accusations typically reveal more about the accuser than the accused. Many fundamentalists who level these charges online seem less concerned with moral reasoning than with projecting their own supposed moral superiority. The stench of hypocrisy is rarely far away when piety becomes a performance.

Ever since Richard Dawkins introduced the concept of the “meme” — a unit of cultural inheritance analogous to a gene — in The Selfish Gene, we have had a clear framework for understanding how cultural traits evolve. Memes form complex structures known as “memplexes”, and some of these can behave parasitically, using their hosts to ensure their own propagation.

Just as evolving organisms form clades with shared major features but differing details, human cultures share foundational moral principles — prohibitions against needless killing, reciprocal respect (“treat others as you would want to be treated”), and the protection of children, among others. What varies are the details, both across time and geography.