Refuting Creationism

What Modern Humans Were Doing In West Papua

40,000 Years Before 'Creation Week'

What Modern Humans Were Doing In West Papua

40,000 Years Before 'Creation Week'

Rock paintings provide evidence of social change in West Papua.

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

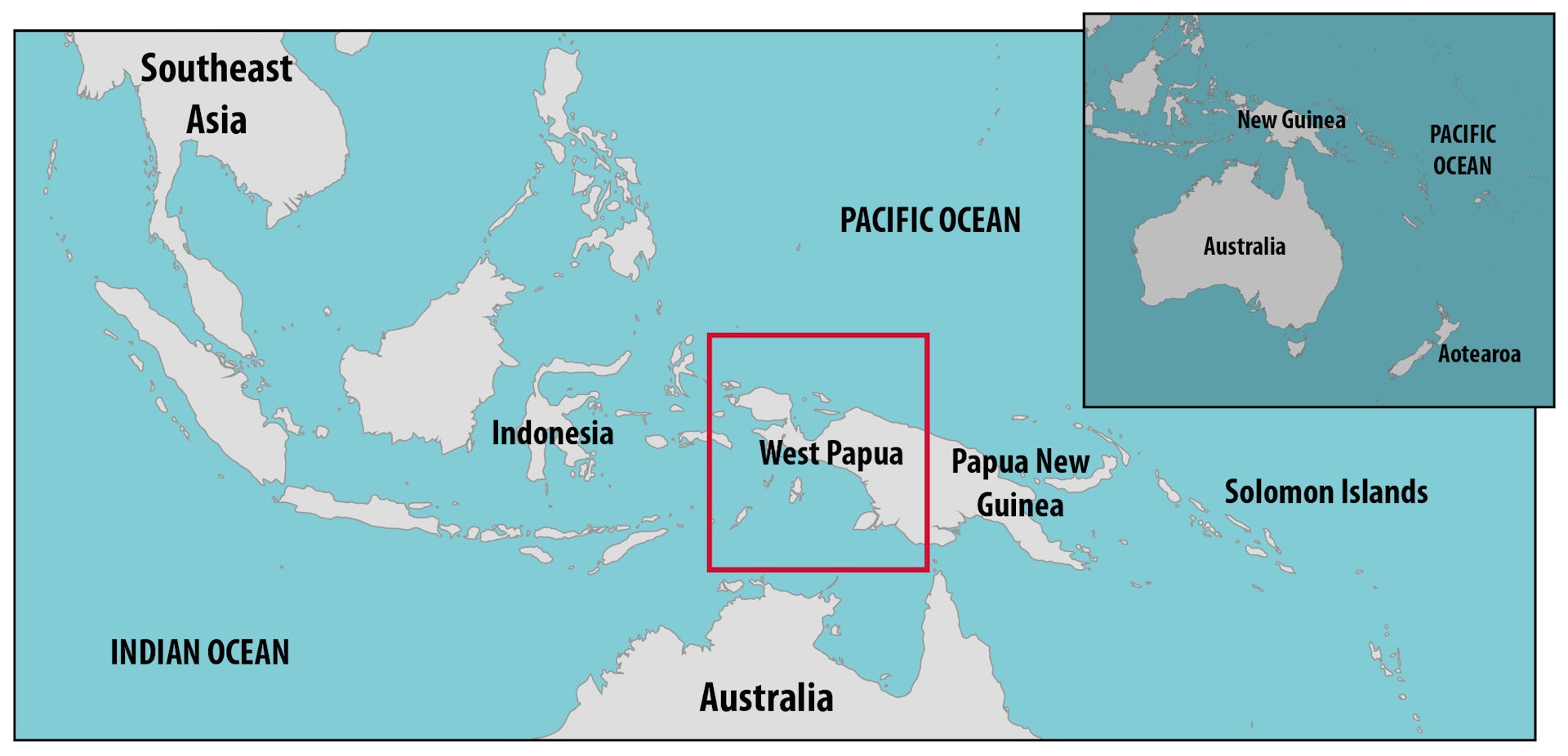

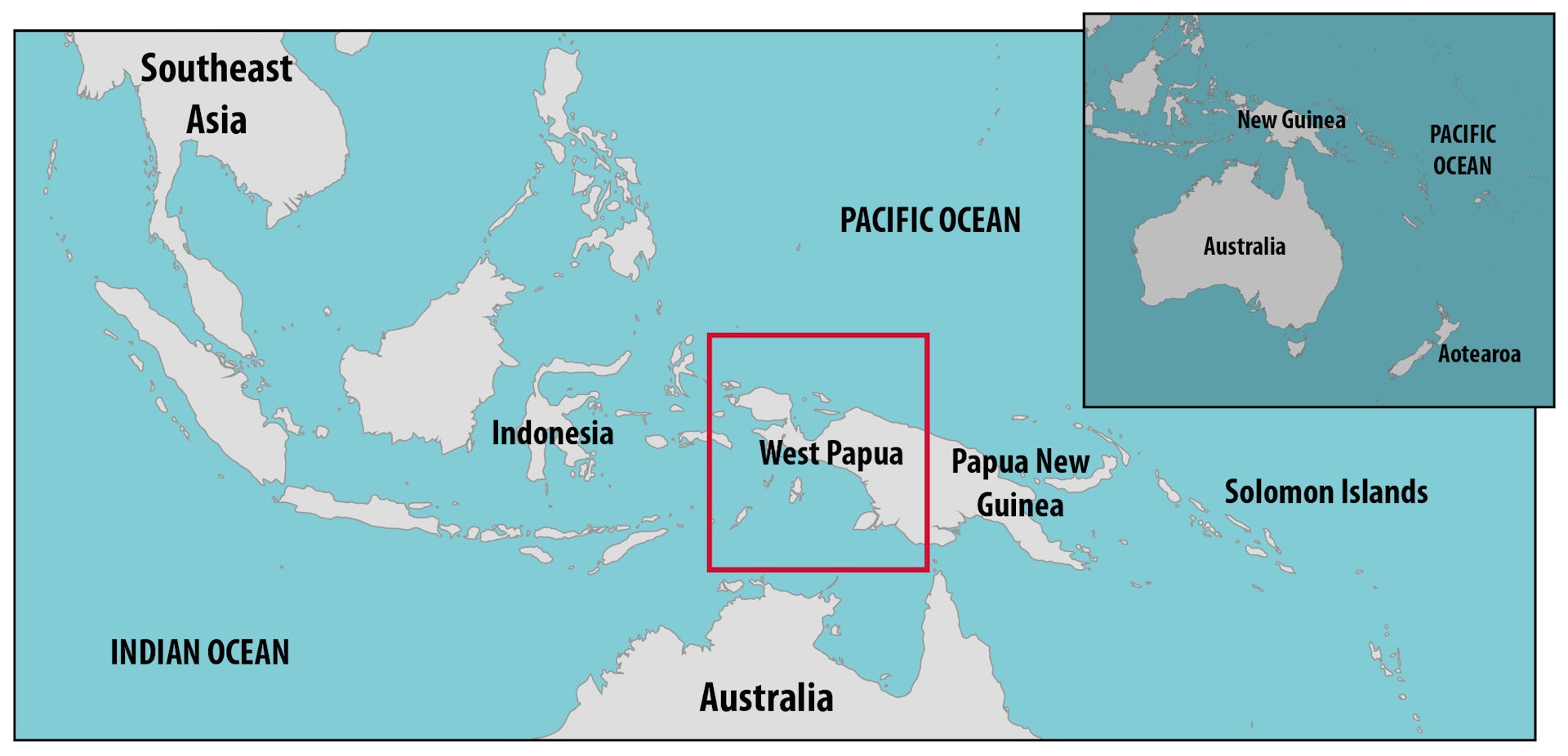

Archaeological evidence shows that people migrating from Eurasia into the Australasian region came through West Papua.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

According to the recently published book, West New Guinea: Social, Biological, and Material Histories, by Professor Dylan Gaffney and Marlin Tolla, modern humans had arrived in what is now West Papua at least 50,000 years ago.

This is approximately 40,000 years before young Earth creationists claim their proposed deity created a small, flat Earth beneath a dome in the Middle East, along with a man formed from dust and a woman from his rib as the founding couple of the human species.

As with approximately 99.9975% of Earth's history, the vast majority of human history occurred long before the supposed ‘Creation Week’. The established record of human origins and development differs so radically from the narratives found in the Bible and Qur’an that it is remarkable anyone still considers those texts to be authoritative accounts of history or science—or even credible allegories or metaphors for anything resembling reality.

Genetic evidence further shows that, during their migrations, the ancestors of modern Papuans interbred with now-extinct archaic humans known as Denisovans. As a result, while modern Eurasians typically carry around 2% Neanderthal DNA, many populations in Island Southeast Asia and Oceania—including Austronesian peoples—carry up to 3% Denisovan DNA.

The authors, Professor Dylan Gaffney and Marlin Tolla have published an account of the research that went into their book, open access in the online magazine, The Conversation Their article is reproduced here under a Creative Commons License, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Fitting the ‘missing puzzle pieces’ – research sheds light on the deep history of social change in West Papua

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

Owing to its violent political history, West Papua’s vibrant human past has long been ignored.

Unlike its neighbour, the independent country of Papua New Guinea, West Papua’s cultural history is poorly understood. But now, for the first time, we have recorded this history in detail, shedding light on 50 millennia of untold stories of social change.

By examining the territory’s archaeology, anthropology and linguistics, our new book fits together the missing puzzle pieces in Australasia’s human history. The book is the first to celebrate West Papua’s deep past, involving authors from West Papua itself, as well as Indonesia, Australasia and beyond.

The new evidence shows West Papua is central to understanding how humans moved from Eurasia into the Australasian region, how they adapted to challenging new environments, independently developed agriculture, exchanged genes and languages, and traded exquisitely crafted objects.

Archaeological evidence shows that people migrating from Eurasia into the Australasian region came through West Papua.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

During the Pleistocene epoch (2.5 million to 12,000 years ago), West Papua was connected to Australia in a massive continent called Sahul.

Archaeological evidence from the limestone chamber of Mololo Cave shows some of the first people to settle Sahul arrived on the shores of present-day West Papua. There they quickly adapted to a host of new ecologies.

The precise date of arrival of the first seafaring groups on Sahul is debated. However, a tree resin artefact from Mololo has been radiocarbon dated to show this happened more than 50,000 years ago.

Genetic analyses support this early arrival time to Sahul. Our work suggests these earliest seafarers crossed along the northern route, one of two passages through the Indonesian islands.

Human dispersal to West Papua during the Pleistocene epoch (about 50,000 years ago) and during the Lapita period (more than 3,000 years ago).

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

In the same way modern European populations retain about 2% of Neanderthal ancestry, many West Papuans retain about 3% of Denisovan heritage.

As the Earth warmed at the end of the Pleistocene, rising seas split Sahul apart. The large savannah plains that joined West Papua and Papua New Guinea to Australia were submerged around 8,000 years ago. Much of West Papua’s southern and western coastlines became islands.

Social transformations during the past 10,000 years

As environments changed, so did people’s cuisine and culture.

We know from sites in Papua New Guinea that people developed their own agricultural systems between 10,000 and 6,000 years ago, at a similar time to innovations in Asia and the Americas. However, agricultural systems were not universally adopted across the island.

New chemical evidence from human tooth enamel in West Papua shows people retained a wide variety of diets, from fish and shellfish to forest plants and marsupials.

One of the key unanswered questions in West Papua’s history is when cultivation emerged and how it spread into other regions, including Southeast Asia. Taro, bananas, yams and sago were all initially cultivated in New Guinea and have become important staple crops around the world.

Moses Dialom, an archaeological fieldwork collaborator from the Raja Ampat Islands, examines excavated artefacts at Mololo Cave.

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

Lapita pottery makers spoke Austronesian languages, which became the ancestors of today’s Polynesian languages, including Māori.

New pottery discoveries from Mololo Cave suggest the ancestors of Lapita pottery makers existed somewhere around West Papua. Finding the location of these ancestral Lapita settlements is a major priority for archaeological research in the territory.

Rock paintings provide evidence of social change in West Papua.

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

At all times in the past, people had a rich and complex material culture. But only a small fraction of these objects survive for archaeologists to study, especially in humid tropical conditions.

People settled diverse environments around West Papua, including montane cloud forests (upper left), lowland rainforests (upper right), mangrove swamps (lower left) and coastal beaches (lower right).

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

From the early 1800s, when West Papua was part of the Dutch East Indies, colonial administrators, scientists and explorers exported tonnes of West Papuan artefacts to European museums. Sometimes the objects were traded or gifted, other times stolen outright.

In the early 1900s, many objects were also burned by missionaries who saw Indigenous material culture as evidence of paganism. The West Papuan objects that now inhabit museums in Europe, America, Australia and New Zealand are connections between modern people and their ancestral traditions.

Sometimes these objects represent people’s direct ancestors. Major work is currently underway to connect West Papuans with these collections and to repatriate some of these objects to museums in West Papua. Unfortunately, funding remains a central issue for these museums.

Many West Papuans continue to produce and use wooden carvings, string bags and shell ornaments. Anthropologists have described how people are actively reconfiguring their material culture, especially given the presence of new synthetic materials and a cash economy.

A montage of images showing West Papuan archaeologists in the field. (A) Klementin Fairyo, left, is setting up a new excavation. (B) Martinus Tekege excavating pottery. (C) Sonya Kawer with wartime archaeology. (D) Abdul Razak Macap, right, sieving for archaeological artefacts at Mololo Cave.

Klementin Fairyo, Martinus Tekege, Sonya Kawer, Abdul Razak Macap, CC BY-SA

Despite our new findings, West Papua remains an enigma for researchers. It has a land area twice the size of Aotearoa New Zealand, but there are fewer than ten known archaeological sites that have been radiocarbon dated.

By contrast, Aotearoa has thousands of dated sites. This means West Papua is the least well researched part of the Pacific and there is much more work to be done. Crucially, Papuan scholars need to be at the heart of this research.

Dylan Gaffney, Associate Professor of Palaeolithic Archaeology, University of Oxford and Marlin Tolla, Researcher in Archaeology, Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The fact that this ideology demands such elaborate mental contortions to shield its adherents from established scientific reality reveals something deeper: the movement is not merely about faith, but also about control. These intellectual evasions serve to protect the authority and political agenda of its leadership, rather than to pursue truth.

Advertisement

Prices correct at time of publication. for current prices.

Last Modified: Thu Apr 03 2025 19:30:59 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time)

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.