From dinosaurs to birds: the origins of feather formation - Medias - UNIGE

Feathers provide a fascinating example of how evolution can repurpose structures over time. Initially evolving in response to one set of selective pressures, feathers later opened the door for entirely new functions unrelated to their original purpose.

Early feathers appeared among dinosaurs primarily as an adaptation for thermoregulation. Simple, filamentous feathers offered significantly better insulation than traditional reptilian scales, helping dinosaurs maintain stable body temperatures. Among bipedal theropod dinosaurs, these insulating feathers eventually evolved into more complex structures, freeing forelimbs to develop into wings. Feathers subsequently became specialized for powered flight, having first likely served intermediate functions such as display or gliding.

The presence of insulating feathers likely provided a survival advantage during the dramatic climate changes following the asteroid impact that marked the end of the Cretaceous period, approximately 66 million years ago, contributing to the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs.

This is why we see a clear progression through the fossil record, unlike what would be expected of an intelligent design process, where birds, complete with flight feathers, would be expected to make a sudden appearance without ancestry.

Today, feathers in modern birds retain their important role in thermoregulation while also facilitating flight and serving as display structures. Vibrant and diverse plumage has evolved under sexual selection pressures, playing a crucial role in mating rituals, mate choice, and reinforcing genetic isolation among closely related species, thereby preventing hybridization.

What information do you have on the fossil evidence for the evolution of feathers from those found on dinosaurs to those of flying birds? Fossil evidence documenting the evolution of feathers from dinosaurs to modern birds has greatly improved in recent decades, particularly with discoveries from China. Key points include:But the key changes that lead to the evolution of feathers from reptilian scales had remained elusive until now. Now, two researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, have uncovered a key role of a molecular signalling pathway (the Shh pathway) in their formation. They have published their findings in the journal, PLOS Biology, and explained them in a University of Geneve press release:In short, the fossil record clearly demonstrates a gradual progression from simple insulating filaments to complex, asymmetrical flight feathers, directly connecting non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds.

- Filamentous Proto-feathers:

- Early feather-like structures have been identified in fossils of non-avian dinosaurs such as Sinosauropteryx, which lived around 125 million years ago during the early Cretaceous period. These simple, filamentous structures, or "proto-feathers," were likely used primarily for insulation or display.

- Complex Feather Structures:

- More complex feathers resembling those of modern birds appear in later theropods. Fossils like Caudipteryx and Sinornithosaurus from the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous (around 160-120 million years ago) show branching structures with barbs and barbules, although they likely were incapable of sustained powered flight. These feathers probably served as insulation and were possibly used for display or gliding.

- Flight and Transitional Forms:

- Archaeopteryx, often cited as a key transitional fossil (approximately 150 million years old), possessed flight-capable feathers remarkably similar to those of modern birds, with asymmetrical vanes adapted for powered flight. However, Archaeopteryx still retained several dinosaurian traits, such as teeth, a long bony tail, and clawed fingers, clearly illustrating a transitional stage.

- Microraptor and Gliding Flight:

- Fossils of the theropod dinosaur Microraptor (approximately 120 million years ago) feature well-preserved feathers on all four limbs and the tail, forming a wing-like arrangement. This configuration strongly suggests it engaged in gliding flight, indicating experimentation in feathered flight prior to the development of the modern avian flight mechanism.

- Preservation of Pigmentation:

- Remarkably, some feathered dinosaur fossils, like Anchiornis, have preserved microscopic structures (melanosomes) indicating pigment patterns. These have provided insights into feather coloration and display functions, further highlighting evolutionary pressures beyond thermoregulation.

From dinosaurs to birds: the origins of feather formation

UNIGE scientists reveal the key role of specific genes in feather development, providing insights into their evolution from dinosaurs.

Feathers, essential for thermoregulation, flight, and communication in birds, originate from simple appendages known as proto-feathers, which were present in certain dinosaurs. By studying embryonic development of the chicken, two researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) have uncovered a key role of a molecular signalling pathway (the Shh pathway) in their formation. This research, published in the journal PLOS Biology, provides new insights into the morphogenetic mechanisms that led to feather diversification throughout evolution.

Feathers are among the most complex cutaneous appendages in the animal kingdom. While their evolutionary origin has been widely debated, paleontological discoveries and developmental biology studies suggest that feathers evolved from simple structures known as proto-feathers. These primitive structures, composed of a single tubular filament, emerged around 200 million years ago in certain dinosaurs. Paleontologists continue to discuss the possibility of their even earlier presence in the common ancestor of dinosaurs and pterosaurs (the first flying vertebrates with membranous wings) around 240 million years ago.

The emergence of proto-feathers likely marked the first key step in feather evolution.

Proto-feathers are simple, cylindrical filaments. They differ from modern feathers by the absence of barbs and barbules, and by the lack of a follicle—an invagination at their base. The emergence of proto-feathers likely marked the first key step in feather evolution, initially providing thermal insulation and ornamentation before being progressively modified under natural selection to give rise to the more complex structures that enabled flight.

The laboratory of Michel Milinkovitch, professor at the Department of Genetics and Evolution in the Faculty of Science at UNIGE, studies the role of molecular signaling pathways (communication systems that transmit messages within and between cells), such as the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) pathway, in the embryonic development of scales, hair, and feathers in modern vertebrates. In a previous study, the Swiss scientists stimulated the Shh pathway by injecting an activating molecule into the blood vessels of chicken embryos and observed the complete and permanent transformation of scales into feathers on the bird’s feet.

Recreating the first dinosaur proto-feathers

Since the Shh pathway plays a crucial role in feather development, we wanted to observe what happens when it is inhibited.

Dr. Rory L. Cooper, first-author.

Laboratory of Artificial and Natural Evolution (LANE)

Department of Genetics and Evolution

University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland.

By injecting a molecule that blocks the Shh signaling pathway on the 9th day of embryonic development – just before feather buds appear on the wings – the two researchers observed the formation of unbranched and non-invaginated buds, resembling the putative early stages of proto-feathers.

However, from the 14th day of embryonic development, feather morphogenesis partially recovered. Furthermore, although the chicks hatched with patches of naked skin, dormant subcutaneous follicles were autonomously reactivated, eventually producing chickens with normal plumage.

Our experiments show that while a transient disturbance in the development of foot scales can permanently turn them into feathers, it is much harder to permanently disrupt feather development itself. Clearly, over the course of evolution, the network of interacting genes has become extremely robust, ensuring the proper development of feathers even under substantial genetic or environmental perturbations. The big challenge now is to understand how genetic interactions evolve to allow for the emergence of morphological novelties such as proto-feathers.

Professor Michel C. Milinkovitch, corresponding author.

Laboratory of Artificial and Natural Evolution (LANE)

Department of Genetics and Evolution

University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland.

AbstractIn summary, the authors of this paper demonstrated that inhibiting the Shh pathway caused the developing feathers of embryonic chicks to revert to a form resembling those of feathered dinosaurs. Such a result would be unexpected if feathers had been specifically and intelligently designed for birds, as creationists claim. Under an intelligent design scenario, blocking the Shh pathway should logically prevent feather formation entirely rather than reverting feathers to an ancestral state. Instead, this evidence strongly reinforces the evolutionary origin of modern bird feathers—represented here by the domestic chicken—as modified versions inherited from theropod dinosaur ancestors. Clearly, the evolutionary transition involved critical modifications to the Shh gene that controls this pathway in the developing embryo.

The morphological intricacies of avian feathers make them an ideal model for investigating embryonic patterning and morphogenesis. In particular, the sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway is an important mediator of feather outgrowth and branching. However, functional in vivo evidence regarding its role during feather development remains limited. Here, we demonstrate that an intravenous injection of sonidegib, a potent Shh pathway inhibitor, at embryonic day 9 (E9) temporarily produces striped domains (instead of spots) of Shh expression in the skin, arrests morphogenesis, and results in unbranched and non-invaginated feather buds—akin to proto-feathers—in embryos until E14. Although feather morphogenesis partially recovers, hatched treated chickens exhibit naked skin regions with perturbed follicles. Remarkably, these follicles are subsequently reactivated by seven weeks post-hatching. Our RNA-sequencing data and rescue experiment using Shh-agonism confirm that sonidegib specifically down-regulates Shh pathway activity. Overall, we provide functional evidence for the role of the Shh pathway in mediating feather morphogenesis and confirm its role in the evolutionary emergence and diversification of feathers.

Introduction

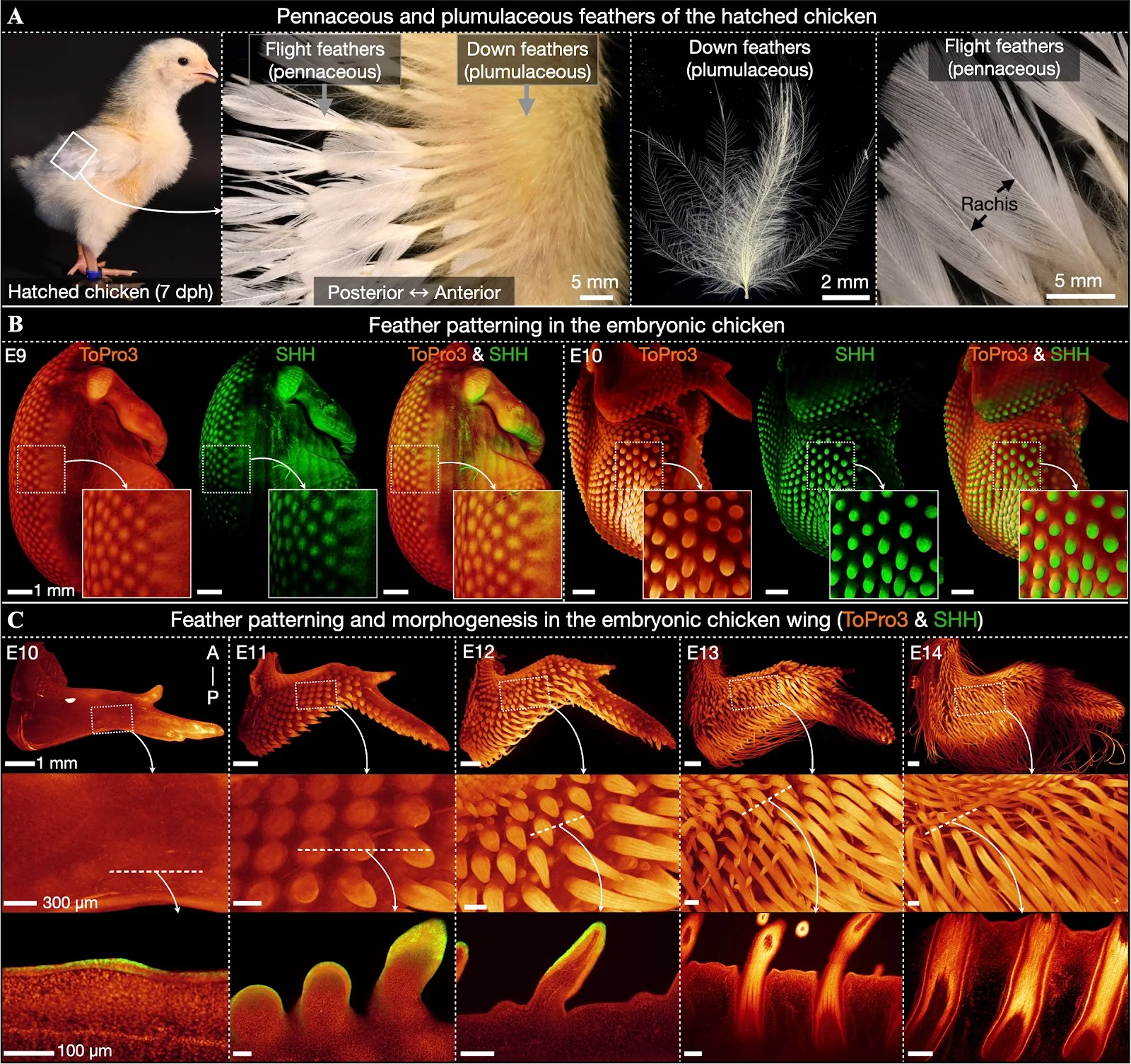

Avian feathers are intricate integumentary appendages, the forms of which vary substantially among species, across body areas, and between juvenile and adult stages. Understanding both the developmental and evolutionary mechanisms underpinning this morphological diversity has long fascinated biologists [1,2]. Although their evolutionary origin has been widely debated, feathers likely first appeared as simple cylindrical monofilaments in the common archosaurian ancestor of dinosaurs and pterosaurs during the Early Triassic [3–5]. Gradually, the morphology of these so-called ‘proto-feathers’ then increased in complexity to first produce simple plumulaceous down-type feathers (which lack a central shaft known as a rachis) and, later, to produce the more highly ordered pennaceous feathers [1,2], including bilaterally symmetric contour feathers and bilaterally asymmetric flight feathers (Fig 1A) [6]. This diversification was necessarily driven by modifications to the spatial expression of conserved developmental genes mediating feather morphogenesis, including the longitudinal domains of sonic hedgehog (Shh) expression observed during feather barb formation [7,8]. However, the precise effects of perturbing such molecular signaling throughout feather morphogenesis remain to be comprehensively investigated in vivo. More generally, feathers provide an ideal model for investigating molecular developmental patterning and morphogenesis [6,9].

.Although feathers arguably constitute the most complex and highly ordered group of integumentary appendages, their early embryonic development shares broad similarities in molecular signaling and morphogenesis with hairs and scales [10–13]. The morphological development of feathers begins with the emergence of an anatomical placode [12,14]—a local epidermal thickening and an underlying aggregation of dermal cells—associated with conserved patterns of gene expression [9]. Indeed, conserved placode signaling constitutes the foundation of integumentary appendages across diverse vertebrate clades, from the scales of sharks to the hairs of mammals [10–13]—with the exception of crocodile head scales [15,16]. The spatial distribution of placodes is widely considered to be mediated through paradigmatic chemical Turing reaction-diffusion dynamics, in which interactions between diffusing activatory and inhibitory morphogens give rise to stable periodic patterns [17–23]. Research regarding feather propagation in the chicken, and scale propagation in snakes, has revealed that chemical reaction-diffusion patterning is coupled with mechanical processes. Indeed, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling triggers the aggregation of dermal cells which mechanically compress the overlying epidermis, thereby initiating subsequent local molecular signaling [23–26]. The outgrowth of feather placodes then gives rise to elongated and cylindrical feather buds, whilst invagination at their base gives rise to the follicle [6]. Finally, the feather bud divides into individual longitudinal filaments known as barbs, a process termed “branching morphogenesis”. Fig 1. Feather development in embryonic chicken. (A) Hatched chickens at seven day post-hatching (7 dph) exhibit both pennaceous (with a central rachis) and plumulaceous (without a rachis) feather types. (B) At E9, LSFM reveals feather placodes covering most of the dorsum and expressing SHH protein (visualized by immunofluorescence). By E10, these placodes undergo considerable outgrowth and SHH becomes localized to the posterior tip of developing units. (C) Feather placodes first emerge on the posterior edge of the wings at E10, before propagating to cover the entire wing by E11. Optical sections reveal epidermal SHH immunofluorescence from E10 to E12. At E12, the longitudinal barbs associated with branching morphogenesis are visible, and by E13, invagination of the follicle is well-advanced. These units continue to develop until E14, at which point feather buds are elongated, keratinized, and exhibit a longitudinal pattern of cell density corresponding to the future feather barbs.

Fig 1. Feather development in embryonic chicken. (A) Hatched chickens at seven day post-hatching (7 dph) exhibit both pennaceous (with a central rachis) and plumulaceous (without a rachis) feather types. (B) At E9, LSFM reveals feather placodes covering most of the dorsum and expressing SHH protein (visualized by immunofluorescence). By E10, these placodes undergo considerable outgrowth and SHH becomes localized to the posterior tip of developing units. (C) Feather placodes first emerge on the posterior edge of the wings at E10, before propagating to cover the entire wing by E11. Optical sections reveal epidermal SHH immunofluorescence from E10 to E12. At E12, the longitudinal barbs associated with branching morphogenesis are visible, and by E13, invagination of the follicle is well-advanced. These units continue to develop until E14, at which point feather buds are elongated, keratinized, and exhibit a longitudinal pattern of cell density corresponding to the future feather barbs.

Previous research has also investigated the post-embryonic development of feathers. For example, the establishment of a Wnt3a signaling gradient appears to be required for the development of bilaterally symmetric contour feathers (but not radially symmetric plumulaceous feathers) during post-embryonic development [27]. Furthermore, coordinated adjustment of cell shape and adhesion, via the contraction of basal keratinocyte filopodia in the follicle, may contribute to the regulation of branching morphogenesis of pennaceous feathers [28]. Here, we investigate the embryonic development of the plumulaceous down-type feathers in the chicken.

The sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway is a key regulator of diverse developmental processes [29,30]. Canonical Shh signaling begins with the SHH ligand binding to its receptor Patched (PTCH), thereby reversing the repression of the transmembrane protein Smoothened (SMO). The latter subsequently activates signaling via the transcription factor GLI, an intracellular zinc finger protein that triggers downstream transcription [31–33]. The Shh pathway plays multiple roles during feather development [34]. First, we have shown that transient in vivo agonism of Shh pathway signaling in chicken at embryonic day 11 (E11), through a single intravenous injection of smoothened agonist (SAG), triggers a complete and permanent transition from reticulate foot scales to feathers [35]. Remarkably, the resulting juvenile down-type ectopic feathers subsequently transition into adult regenerative bilaterally symmetric contour feathers, without the need for sustained SAG treatment, indicating that the over-expression of the Shh pathway at E11 induces a permanent shift in developmental fate of the corresponding placodes. Hence, the Shh pathway is clearly involved in the specification of avian skin appendages. Second, Shh mediates feather bud outgrowth by regulating interactions between the epidermis and mesenchyme [36] and may mediate the proliferation of dermal progenitor cells during morphogenesis [37]. Third, the relative level of Shh signaling within the posterior edge of the wing is involved in determining the location of specialized pennaceous flight feathers [38]. Fourth, feather branching morphogenesis in the embryonic chicken requires the spatial patterning of Shh through a reaction-diffusion mechanism that also involves the bone morphogenetic protein, Bmp2 [7,8]. In this proposed activator-inhibitor model, diffusing Shh activates its own transcription, as well as the transcription of Bmp2, which then inhibits Shh [8]. The stationary striped pattern of expression that arises from this mechanism provides a molecular template defining the position of individual feather barbs, i.e., Shh and Bmp2 are observed in characteristic longitudinal expression domains defining the edges of individual barb ridges [7,8]. Although replication-competent avian retrovirus infection has previously been used to manipulate the expression domains of Shh and Bmp2 that dictate feather barb formation [8], functional in vivo evidence regarding the roles of Shh during subsequent feather morphogenesis remains limited.

Here, we investigate feather development in the chicken. First, we present light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) imaging data regarding the normal patterning and morphogenesis of embryonic feathers. Next, we use precise intravenous in-ovo injections [35,39] of sonidegib to pharmacologically inhibit Shh pathway signaling during feather development at embryonic day 9 (E9), i.e., at the placodal stage preceding feather-bud outgrowth on the wings. This treatment temporarily modifies Shh expression to produce striped domains, temporarily arrests morphogenesis, and results in unbranched and non-invaginated feather buds—akin to putative proto-feathers—in embryos until E14. Although feather morphogenesis partially recovers, hatched sonidegib-treated chickens exhibit naked regions of the skin surface with dormant and perturbed follicles. Remarkably, these dormant follicles are subsequently reactivated before seven weeks of post-embryonic development. Using bulk RNA sequencing (RNAseq) and a rescue experiment (with SAG), we show that sonidegib specifically reduces Shh pathway signaling. Overall, we provide comprehensive functional evidence for the role of the Shh pathway in mediating feather morphogenesis in the chicken, supporting the hypothesis that modified Shh signaling has contributed to the evolutionary diversification of feathers.

Fig 2. WMISH reveals that sonidegib treatment arrests feather branching morphogenesis.

Fig 2. WMISH reveals that sonidegib treatment arrests feather branching morphogenesis.

(A) The feathers of DMSO-treated control samples undergo normal patterning and morphogenesis [9], including the emergence of longitudinal Shh expression domains associated with branching morphogenesis from E12 to E13 [7,8]. (B) Samples treated with 100 µg sonidegib exhibit similar feather patterning to control samples but with slightly perturbed feather bud outgrowth (units are shorter across comparable embryonic stages). (C, D) Samples treated with either 200 or 300 µg sonidegib exhibit large striped expression domains of Shh at E10, demonstrating that these treatments temporarily modify the underlying reaction-diffusion dynamics. Normal spotted patterning recovers by E11 with Shh expression restricted to individual feather domains. However, subsequent morphogenesis from E11 to E13 remains perturbed as feather buds undergo substantially less outgrowth than in control samples. (D) At E13, samples treated with 300 µg sonidegib also reveal a reduction in longitudinal Shh expression domains associated with feather branching morphogenesis. (A–D, bottom row) As Shh WMISH becomes problematic after E13, only the morphological effect of sonidegib-induced dose-dependent reduction in feather bud outgrowth is shown at E14 (also shown in S1 Fig). Fig 4. Naked skin regions in sonidegib-treated embryos contain perturbed follicles at E21.

Fig 4. Naked skin regions in sonidegib-treated embryos contain perturbed follicles at E21.

(A) Control samples exhibit normal coverage of keratinized and filamentous feathers. LSFM of nuclear stained (TO-PRO-3) control samples reveals deeply embedded feather follicles from which highly keratinized feather shafts emerge, consisting of multiple individual barbs (white arrows). (B) The anterior wings of samples treated with 300 µg sonidegib exhibit naked regions of skin adorned with perturbed sub-epidermal feather follicles (blue arrows) that completely lack the outgrowth of feather buds (white arrows), and exhibit less tissue differentiation than observed in control samples. Therefore, sonidegib treatment does not abolish the patterning of feather follicles, but instead dramatically perturbs feather bud and follicle morphogenesis in these regions, resulting in naked areas of the skin. Fig 6. SAG treatment rescues sonidegib-perturbed feather morphogenesis at E14.

Fig 6. SAG treatment rescues sonidegib-perturbed feather morphogenesis at E14.

Embryos were treated with SAG, a SMO agonist, together or following sonidegib delivery at E9. (A) Control embryos injected with DMSO at E9 exhibit normal elongated, filamentous feathers at E14. (B) Embryos treated at E9 with 300 µg sonidegib exhibit at E14 substantially reduced units that lack both branching and follicle invagination (blue arrow). (C) However, the combined injection of 300 µg sonidegib and 50 µg SAG at E9, prevents abnormal morphogenesis of feather buds. (D) Treatment with 100 µg SAG at E10 rescues feather morphogenesis in samples treated with 300 µg sonidegib at E9. (E) Treatment with 150 µg SAG at E11 only partially rescues feather morphogenesis in samples treated with 300 µg sonidegib at E9 (i.e., feather buds remain shorter at E14) probably because of a shorter recovery time (i.e., E11–E14). LSFM sections in the bottom panels reveal normal feather branching (white arrows) and follicle morphogenesis in the control and in all samples treated with both sonidegib and SAG, although samples treated with SAG at E11 exhibit reduced follicle invagination (E, bottom panel).

Fig 3. Sonidegib treatment arrests feather bud outgrowth and invagination.

Fig 3. Sonidegib treatment arrests feather bud outgrowth and invagination.

We use LSFM of nuclear stained (TO-PRO-3) chicken wings at E14 to investigate the morphological effect of sonidegib treatment. (A) Control samples exhibit normal development of elongated feather buds with well-advanced follicles and visible barb ridges (white arrow). (B, C) We observe a dose-dependent effect of sonidegib treatment, with higher doses resulting in shorter feather buds and less advanced follicle development. (D) Samples treated with 300 µg sonidegib exhibit minimal feather bud outgrowth, the fusion of feather buds (white oval dotted outline), absent branching morphogenesis, and no follicle invagination (blue arrow). Fig 5. Bulk RNA sequencing reveals that sonidegib treatment down-regulates Shh pathway signaling.

Fig 5. Bulk RNA sequencing reveals that sonidegib treatment down-regulates Shh pathway signaling.

(A) Samples were injected with either DMSO (controls) or 300 µg sonidegib at E9. Wings were then dissected for RNA sequencing from E10 to E13, with four biological replicates used for each treatment at each stage. (B) From E11 onwards, PCA reveals a clear separation between control and treated samples. (C) Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (filtered by a fold change of ≥1.4 and a false-discovery rate (FDR) adjusted P-value of ≤0.05) are shown in volcano plots for four embryonic stages. At E10, Shh pathway members Ptch1, Ptch2 and Gli1 are down-regulated. From E11 to E13, both Ptch2 and Shh are persistently down-regulated in treated samples relative to controls. See file S1 Data for the data underlying the graphs shown in the figure. Fig 7. Post-embryonic effect of sonidegib treatment.

Fig 7. Post-embryonic effect of sonidegib treatment.

(A) Control samples exhibit complete coverage of (yellow) plumulaceous down-type feathers from 1 dph (top row) until 7 dph (second row). By 28 dph (third row), down-type feathers are observed transitioning into (white) pennaceous contour feathers. This process is complete by 49 dph (bottom row). (B) Samples treated with 100 µg sonidegib exhibit slightly more sparsely patterned feathers, with some patches of skin visible through their plumage. However, by 49 dph, their feather coverage appears indistinguishable from controls. (C, D) Samples treated with either 200 or 300 µg sonidegib exhibit large regions of naked skin on their backs, from 1 dph to 28 dph. Upon closer inspection, these naked regions exhibit regularly patterned skin elevations, which likely correspond to dormant subepidermal follicles (as shown in Fig 4B). By 49 dph, the feather coverage of samples treated with 200 or 300 µg sonidegib recovers and appears comparable to both controls and samples treated with 100 µg sonidegib.

Cooper RL, Milinkovitch MC (2025)

In vivo sonic hedgehog pathway antagonism temporarily results in ancestral proto-feather-like structures in the chicken. PLoS Biol 23(3): e3003061. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3003061

Copyright: © 2025 The authors.

Published by PLoS. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

The Malevolent Designer: Why Nature's God is Not Good

Illustrated by Catherine Webber-Hounslow.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.