|

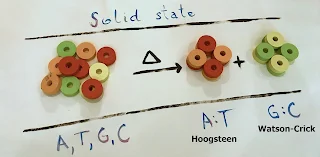

| From the mixture of all four nucleobases, A:T pairs emerged at about 100 degrees Celsius and G:C pairs formed at 200 degrees Celsius. Credit: Ruđer Bošković Institute, Ivan Halasz |

It's been one of those awful weeks for Creationists again.

Not only did we have those lovely wasps embedded in 25-million-year-old amber, and then their beloved Covidiot In Chief, Donald Trump being laid low with the virus he had pronounced to be a hoax and a mild illness that would all be over by April, but now we have another shovel-full thrown into their favourite god-shaped hole, abiogenesis. Abiogenesis is the current fall-back of every creationist who runs out of arguments against evolution, and to which they cling like a fool to a deck-chair in the face of an on-rushing tsunami.

This time we have news that a team led by Ivan Halasz from the Ruđer Bošković Institute and Ernest Meštrović from the pharmaceutical company Xellia have shown just how easy it must have been to create DNA by perfectly natural processes in conditions which would have been found on the early Earth. Their findings were published a few days ago in the journal Chemical Communications, regrettably behind a paywall. However, the news release from the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), A Research Centre of the Helmholtz Association, explains the problem and the team's findings:

“One of the most intriguing questions in the search for the origin of life is how the chemical selection occurred and how the first biomolecules formed,” says Tomislav Stolar from the Ruđer Bošković Institute in Zagreb, the first author on the paper. While living cells control the production of biomolecules with their sophisticated machinery, the first molecular and supramolecular building blocks of life were likely created by pure chemistry and without enzyme catalysis. For their study, the scientists investigated the formation of nucleobase pairs that act as molecular recognition units in the Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA).

Our genetic code is stored in the DNA as a specific sequence spelled by the nucleobases adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). The code is arranged in two long, complementary strands wound in a double-helix structure. In the strands, each nucleobase pairs with a complementary partner in the other strand: adenine with thymine and cytosine with guanine.

“Only specific pairing combinations occur in the DNA, but when nucleobases are isolated they do not like to bind to each other at all. So why did nature choose these base pairs?” says Stolar. Investigations of pairing of nucleobases surged after the discovery of the DNA double helix structure by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953. However, it was quite surprising that there has been little success in achieving specific nucleobase pairing in conditions that could be considered as prebiotically plausible.

“We have explored a different path,” reports co-author Martin Etter from DESY. “We have tried to find out whether the base pairs can be generated by mechanical energy or simply by heating.” To this end, the team studied methylated nucleobases. Having a methyl group (-CH3) attached to the respective nucleobases in principle allows them to form hydrogen bonds at the Watson-Crick side of the molecule. Methylated nucleobases occur naturally in many living organisms where they fulfil a variety of biological functions.

In the lab, the scientists tried to produce nucleobase pairs by grinding. Powders of two nucleobases were loaded into a milling jar along with steel balls, which served as the grinding media, while the jars were shaken in a controlled manner. The experiment produced A:T pairs which had also been observed by other scientists before. Grinding however, could not achieve formation of G:C pairs.

In a second step, the researchers heated the ground cytosine and guanine powders. “At about 200 degrees Celsius, we could indeed observe the formation of cytosine-guanine pairs,” reports Stolar. In order to test whether the bases only form the known pairs under thermal conditions, the team repeated the experiments with mixtures of three and four nucleobases at the P02.1 measuring station of DESY's X-ray source PETRA III. Here, the detailed crystal structure of the mixtures could be monitored during heating and formation of new phases could be observed.

“At about 100 degrees Celsius, we were able to observe the formation of the adenine-thymine pairs, and at about 200 degrees Celsius the formation of Watson-Crick pairs of guanine and cytosine,” says Etter, head of the measuring station. “Any other base pair did not form even when heated further until melting.” This proves that the thermal reaction of nucleobase pairing has the same selectivity as in the DNA.

“Our results show a possible alternative route as to how the molecular recognition patterns that we observe in the DNA could have been formed,” adds Stolar. “The conditions of the experiment are plausible for the young Earth that was a hot, seething cauldron with volcanoes, earthquakes, meteorite impacts and all sorts of other events. Our results open up many new paths in the search for the chemical origins of life.” The team plans to investigate this route further with follow-up experiments at P02.1.

So, the formation of the pairings seen in DNA in nature were easily established in conditions which probably prevailed in the early years of Earths existence. This finding opens up the possibility that this was the route taken by which early life got going - and, no doubt to the consternation of Creationists, it is reproducible in a laboratory setting, involves nothing more than the operation of the laws of chemistry and physics and can be watched first-hand with suitable equipment.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.