Crucifiction News

What Took Christians So Long to Depict The Crucifixion?

The Louvre, Paris

What Took Christians So Long to Depict The Crucifixion?

The Crucifixion by Andrea Mantegna, painted between 457 and 1459

The central panel of an altarpiece for church of San Zeno, Verona, Italy

The central panel of an altarpiece for church of San Zeno, Verona, Italy

The Louvre, Paris

The crucifixion gap: why it took hundreds of years for art to depict Jesus dying on the cross

As it is Easter, when Christians traditionally celebrate the repugnant notion of vicarious redemption through the blood sacrifice of a supposedly innocent person, I thought it would be good to examine the whole notion of the crucifixion of the legendary founder of the Christian religion, Jesus.

What I'm not going to do is point out the glaring and irreconcilable inconsistences in the accounts of the crucifixion and the alleged resurrection, which betray the fact that any pretense to be eye-witness accounts are just that - pretense.

If you want more information on that you're more than welcome to try the Easter Challenge to see if you can resolve the accounts into a coherent narrative incorporating all the alleged events.

The origins of Easter have nothing to do with the alleged crucifixion of course, being based, at least in part on the Roman festival of Hilaria:

For example, the timing of Easter is determined by the first full moon after the vernal equinox, which was also an important time in the Roman calendar. The Roman festival of Hilaria, which was held in honor of the goddess Cybele, was celebrated around the same time as the vernal equinox and involved parades, feasting, and gift-giving.The name 'Easter' comes from the Old English 'Ēastre', the name of an Anglo-Saxon festival celebrating the spring equinox which was used by the Christian Church as the arbitrary date of the alleged crucifixion of Jesus, which has as much basis in fact as the supposed date of his birth, i.e., none at all.

Reference:

ChatGPT. (2023, April 9). What are the Roman origins of Easter?

- "The Origins of Easter" by Mark Cartwright, Ancient History Encyclopedia: https://www.ancient.eu/article/1294/the-origins-of-easter/

- "Easter" by Christine M. Tomassini, Encyclopædia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Easter-holiday

- "The Pagan Roots of Easter" by Jennifer Billock, History: https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/history-of-easter-origins-of-easter-traditions

Retrieved from https://chat.openai.com/chat

Perhaps the first thing to point out about the story is its unlikelihood.

To understand why so much of the tale is inconsistent and unlikely, it is necessary to understand the way Rome governed the Empire at the time.

The Empire was divided into provinces, of which Judea was one, run by a governor, such as Pontius Pilate (the only historically attested person in the tale). The Roman authorities allowed the local population to be autonomous in such matters as religion and religious traditions and did not normally interfere in how they managed their affairs locally, so long as order was maintained and due allegiance to the emperor was shown, by accepting the authority of the governor.

This would have meant that the Jewish Temple authorities administered the Jewish laws and enforced adherence to the traditions, including punishment for sins such as blasphemy. In polytheistic Rome, there was no such sin as blasphemy under Roman law because Rome was tolerant of other religions and had no state religion as such.

To recap, Jesus was supposedly arrested and charged with blasphemy because he claimed to be the son of God. The story of his arrest involves Roman soldiers, who would have been acting on the instructions of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, not the Jewish religious leaders who had no authority to command Roman soldiers.

However, since there was no such crime of blasphemy under Roman laws, there would have been no reason for Pilate to be involved and Roman soldiers would not have been used to arrest anyone for blasphemy.

So, the first problem is the inclusion of the Roman governor and Roman soldiers in the story.

The second is the supposed trial before Pilate, which would simply never have taken place, although the religious authorities might have asked Pilate for permission to execute a blasphemer according to their local custom and tradition. In fact, the tale has an account of Pilate 'washing his hands' of the affair and declaring that he could find no sin in Jesus and handing him over to the secular authority for trial under Jewish law.

Pilate therefore went forth again, and saith unto them, Behold, I bring him forth to you, that ye may know that I find no fault in him.

John 19:4

That then raises the next problem: the penalty for the sin of blasphemy according to Jewish law was stoning to death, not crucifiction, which was used for common criminals under Roman law, but Jesus had not been convicted under Roman law!

And here, our storyteller betrays his muddle on that point, since they have Pilate saying:

Take ye him, and crucify him: for I find no fault in him.

John 19:6

Why would the Roman governor tell the Jewish leaders to kill Jesus with the method of execution prescribed for crimes under Roman law, having acquitted him of any crime under Roman law?

Clearly, the 1st or 2nd Century author of this tale didn't know the law or history of the time in which they set their tale and combined several different legends into their account, making up some things up to cover over the crack, so we end up with a tale of a supposed blasphemer under Jewish law being executed under Roman law for something that wasn't a crime under Roman law, and not being stoned, which was the penalty under Jewish law for the crime of which he had been convicted under that law.

And the tale is given a curious twist with the inclusion of Barabbas - the rebel released by Pilate on the acclamation of the crowd. Bar means 'Son of ' and Abbas means 'the Father' in Aramaic, so Pilate at the behest of the crowd was releasing the 'Son of the Father', the rebel leader!

And they cried out all at once, saying, Away with this man, and release unto us Barabbas: (Who for a certain sedition made in the city, and for murder, was cast into prison.)And the muddled and inconsistent account of the role of Judas also betrays the later origins of the entire tale. Interestingly, the blame for who killed Jesus has tended to shift back and forth between the Jews and the Romans according to the needs of the time. In the Early Middle Ages when Islam was moving up the Balkans and threatening Venice's trading empire in the Adriatic and Eastern Mediterranean, the Venetian authorities needed Jewish bankers to fund their fight against Islam, so the blame was shifted onto the Romans, but when Medieval kings were in hock to Jewish bankers and needed an excuse for another purge of Jews from their kingdom, a cancellation of all debts to them and confiscation of their property, they were the ones to blame, the Bible being handily ambiguous on the subject.

Luke 23: 18-19

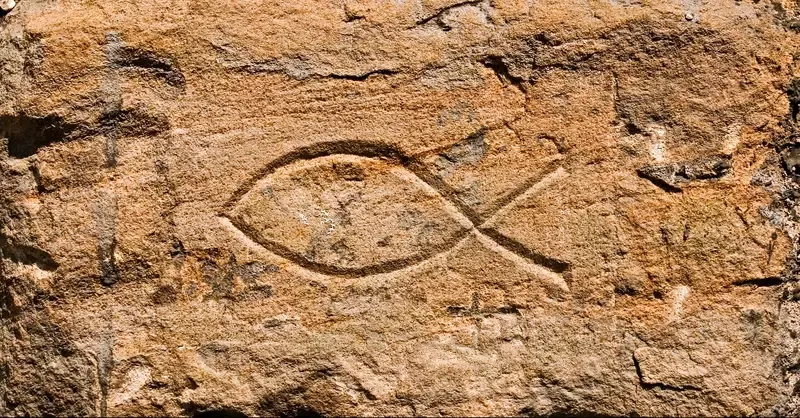

The Christian fish symbol carved into the wall of a cave used as a chapel by the 7th century Saint Fillan in Fife, Scotland.

As this picture shows, it was still in use as late as the 7th Century in Scotland.

That the cross and crucifix were only later adopted by Christianity is explained in an article in The Conversation by Robyn J. Whitaker,, Associate Professor, New Testament, Pilgrim Theological College, University of Divinity, Box Hill, Victoria, Australia. Her article is reprinted here under a Creatives Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency.

The crucifixion gap: why it took hundreds of years for art to depict Jesus dying on the cross

Pavias Andreas, The Crucifixion, second half of the 15th century.

National Gallery - Alexandros Soutsos Museum

Robyn J. Whitaker

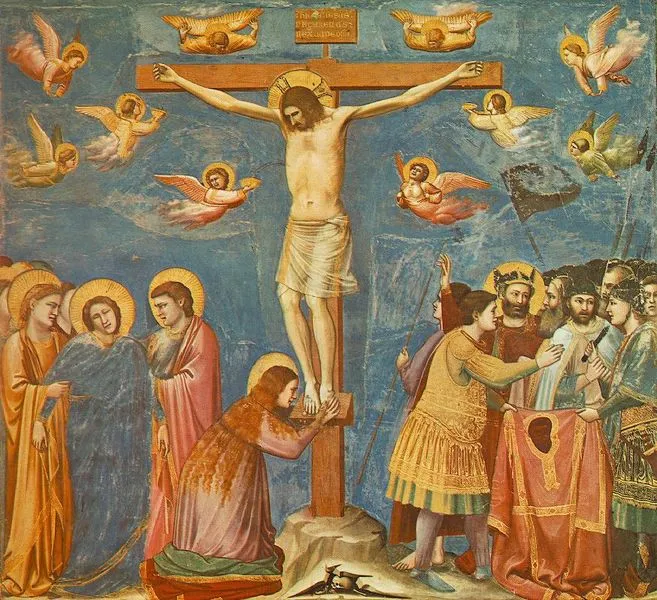

The cross, or crucifix, is arguably the central image of Christianity.

What’s the difference between the two? A cross is just that - an empty cross. It stands as a statement that Jesus is no longer on the cross and thus symbolises his resurrection.

A crucifix, on the other hand, includes the body of Jesus, to more vividly remind viewers of his death.

Many contemporary Christians, from bishops to ordinary folk, wear some kind of cross or crucifix around their neck and it would be rare to find a church that did not have at least one prominently displayed in the building.

While a symbol of faith, it is not just the pious who wear crosses. Madonna famously wore crucifix earrings and necklaces constantly throughout the 1980s and ‘90s. She is quoted as doing so because she provocatively “thought Jesus was sexy”.

The recent ubiquity of the cross as a fashion item means it is sold at everything from cheap tween fashion stores to that jeweller renowned for its little turquoise boxes, where a diamond cross necklace can run in excess of $10,000.

The 2018 Met Gala’s theme, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and Catholic Imagination, further bestowed religious imagery with fashion icon status by making it central to one of the fashion industry’s key events.

Yet the cross was not always the dominant symbol of Christianity that it is now, and would certainly not have been worn as a fashion accessory by early Christians.

In fact, it took centuries for Christians to begin to depict the cross in their art.

An undignified death

While some want to credit Emperor Constantine for the use of the cross as becoming more widespread after the 4th century, it is not that simple. Part of the answer lies in the nature of crucifixion itself.

While crucifixion included some variety in antiquity, it was typically a form of execution reserved for non-elite, non-citizens in the 1st-century Roman Empire.

Slaves, the poor, criminals and political protesters were crucified in their thousands for “crimes” we might today consider minor offences. The types of cross structures might differ, but as a form of execution, crucifixion was brutal and violent, designed to publicly shame the victim by displaying him or her naked on a scaffold, thereby asserting Rome’s power over the bodies of the masses.

That Jesus suffered such an undignified death was an embarrassment to some early Christians. The apostle Paul describes Jesus’ crucifixion as a “stumbling block” or “scandal” to other Jews. Others would imbue it with sacrificial meaning to make sense of how the one claimed as God’s Son would suffer in this way. But the shame associated with this kind of death remained.

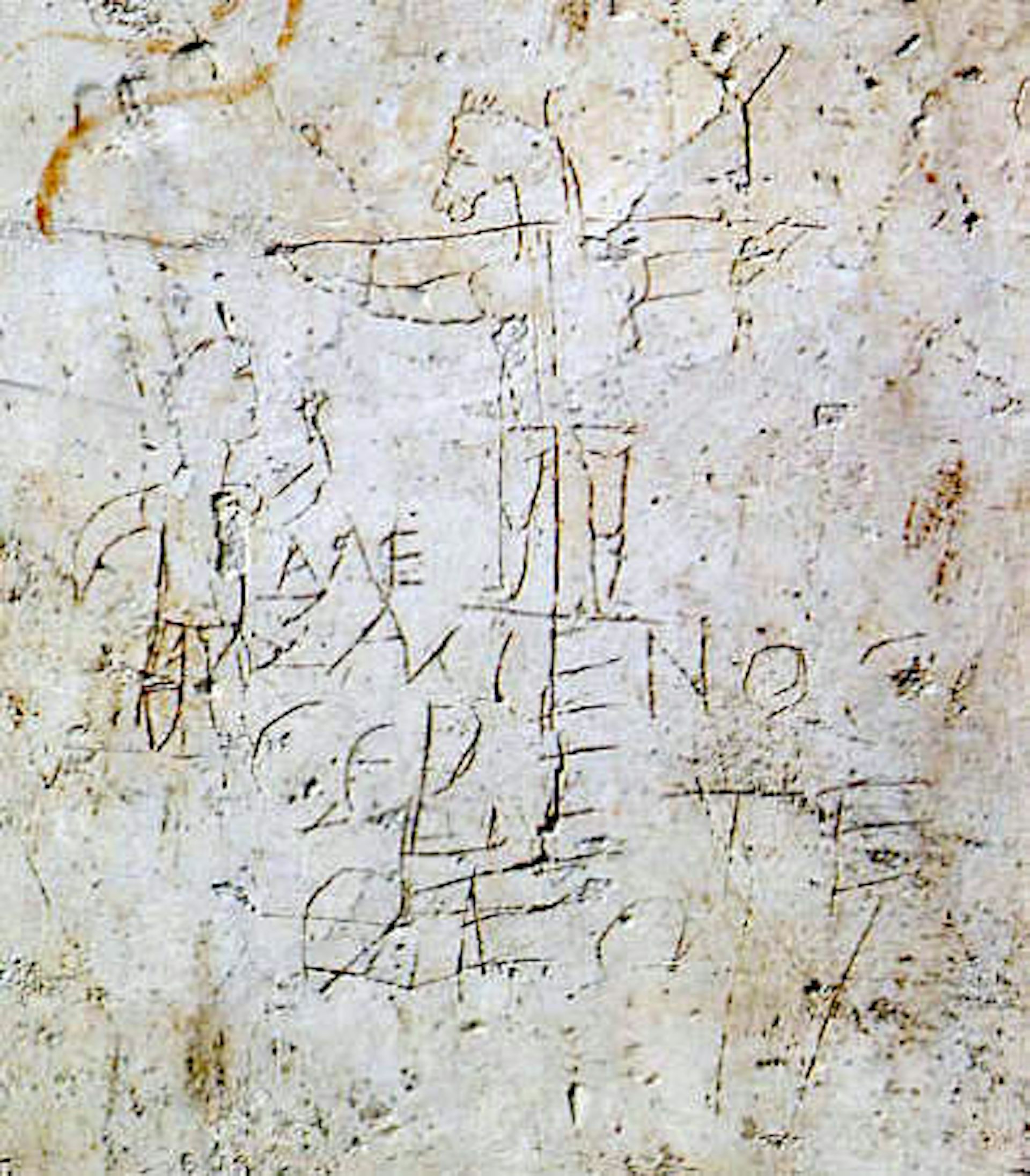

A now infamous piece of graffito, dating to the early 3rd century in Rome, arguably mocks Jesus’ manner of death. Sketched on a wall in Rome, the Alexamenos graffito portrays a donkey-headed male div on a cross under which is written “Alexamenos, worship god”. The suggestion is that the parody was directed at Christians precisely because they worshipped a man who had died by crucifixion.

Christian images

Felicity Harley-McGowan, an expert on crucifixion and early Christian art, argues Christians began to experiment with making their own specifically Christian images around 200 CE, roughly 100-150 years after they began writing about Jesus.

Early works depicting Jesus’ death didn’t always show an overt cross, as in this 440 AD image from the Church of Santa Sabina.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

In the 4th century, Christians began to depict other death scenes from the Bible, such as the raising of Jairus’ daughter, but still not Jesus’ death. Harley-McGowan writes:

it is clear that the earliest representations of deaths in early Christian art were pointed in their focus on actions after the event.Such depictions emphasised healing, new life and resurrection from death. This emphasis is one explanation for why Christians were slow to depict Jesus’ actual death.

One of the earliest extant depictions of Jesus can be found in the Maskell Passion Ivories dating to the early 5th century CE, more than 400 years after his death. These ivories formed a casket panel that includes one death scene amid a range of scenes telling the Jesus story.

Maskell Passion Ivories, one of the earliest extant depictions of Jesus.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

While there is a 3rd-century magical amulet that includes crucifixion imagery (and there may have been other gems and amulets lost to history that associated his resurrection from death in magical terms), depictions of the cross only began to emerge in the 5th century and would remain rare until the 6th.

This magical amulet, carved on jasper, dates to the 3rd century.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

The cross continues to have a complex history, being used as both a symbol of Christian ecclesial power and of white supremacy by groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

There can be beauty, intrigue, magic and terror in these cross traditions.

This Early Byzantine pendant dates to the 6th or 7th century.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

Perhaps, 2,000 years later, it is always both – even when diamond-encrusted.

Robyn J. Whitaker, Associate Professor, New Testament, Pilgrim Theological College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.