Since the first plants appeared, they have diversified into a vast range of forms, and sizes from pond scum to massive trees.

How did plants first evolve into all different shapes and sizes? We mapped a billion years of plant history to find out

Plants come in all manner of shapes and sizes, varying in complexity from simple single-celled algae, through mosses, liverworts and ferns to flowering plants and massive trees.

But how did they get this way?

A team of scientists led by Philip C J Donoghue, Professor of Palaeobiology, University of Bristol, James Clark, Research Associate, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol and Sandy Hetherington, Plant Evolutionary Biologist, The University of Edinburgh, set out to answer this question by looking at certain traits in each major plant group. The traits ranged from fundamentals like the presence of roots, leaves or flowers to the fine details such as the surface topography of pollen grains. All in all, the team collected data on 548 traits from more than 400 living and fossil plants, amounting to more than 130,000 individual observations.

They then used this data to plot the positions of plants, living and extinct in a 'design space', i.e., the theoretical range of possible forms for each major group.

What they found was that there tended to be a burst of diversification soon after the evolution of a major new trait, with the new lineage then tending to settle down to improve on what they had, rather than to innovate - until the next major innovation.

This what we would expect from the way a major new trait, such as the evolution of pollen as the male reproductive cell which could be transferred to the female by wind, insects, etc., so freeing the plants from the need to live in water or damp conditions so the motile male cells could 'swim' to the female, as it still does with the gametophytes - mosses, liverworts and ferns.

This innovation meant plants were not free to diversify into the dryer land between rivers, lakes and coastal margins and so colonise much more of the planet.

The same phenomenon is seen in animals where, for example, terrestrial living freed the early amphibians from dependence on water, except to breed, and the evolution of eggs, freed them even from that dependence; the evolution of flight freed the birds and bats to diversify into the new niches now open to them.

The team's work was published, open access in Nature Plants and is the subject of an article in The Conversation by the three lead authors. Their article is reprinted here under a Creative |Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

How did plants first evolve into all different shapes and sizes? We mapped a billion years of plant history to find out

From minuscule moss to colourful flowers and tall trees.

Philip Donoghue / James Clark

Philip C J Donoghue, University of Bristol; James Clark, University of Bristol, and Sandy Hetherington, The University of Edinburgh

Plants range from simple seaweeds and single-celled pond scum, through to mosses, ferns and huge trees. Palaeontologists like us have long debated exactly how this diverse range of shapes and sizes emerged, and whether plants emerged from algae into multicellular and three-dimensional forms in a gradual flowering or one big bang.

To answer this question, scientists turned to the fossil record. From those best-preserved examples, like trilobites, ammonites and sea urchins, they have invariably concluded that a group’s range of biological designs is achieved during the earliest periods in its evolutionary history. In turn, this has led to hypotheses that evolutionary lineages have a higher capacity for innovation early on and, after this first phase of exuberance, they stick with what they know. This even applies to us: all the different placental mammals evolved from a common ancestor surprisingly quickly. Is the same true of the plant kingdom?

In our new study, we sought to answer this question by looking for certain traits in each major plant group. These traits ranged from the fundamental characteristics of plants – the presence of roots, leaves or flowers – to fine details that describe the variation and ornamentation of each pollen grain. In total, we collected data on 548 traits from more than 400 living and fossil plants, amounting to more than 130,000 individual observations.

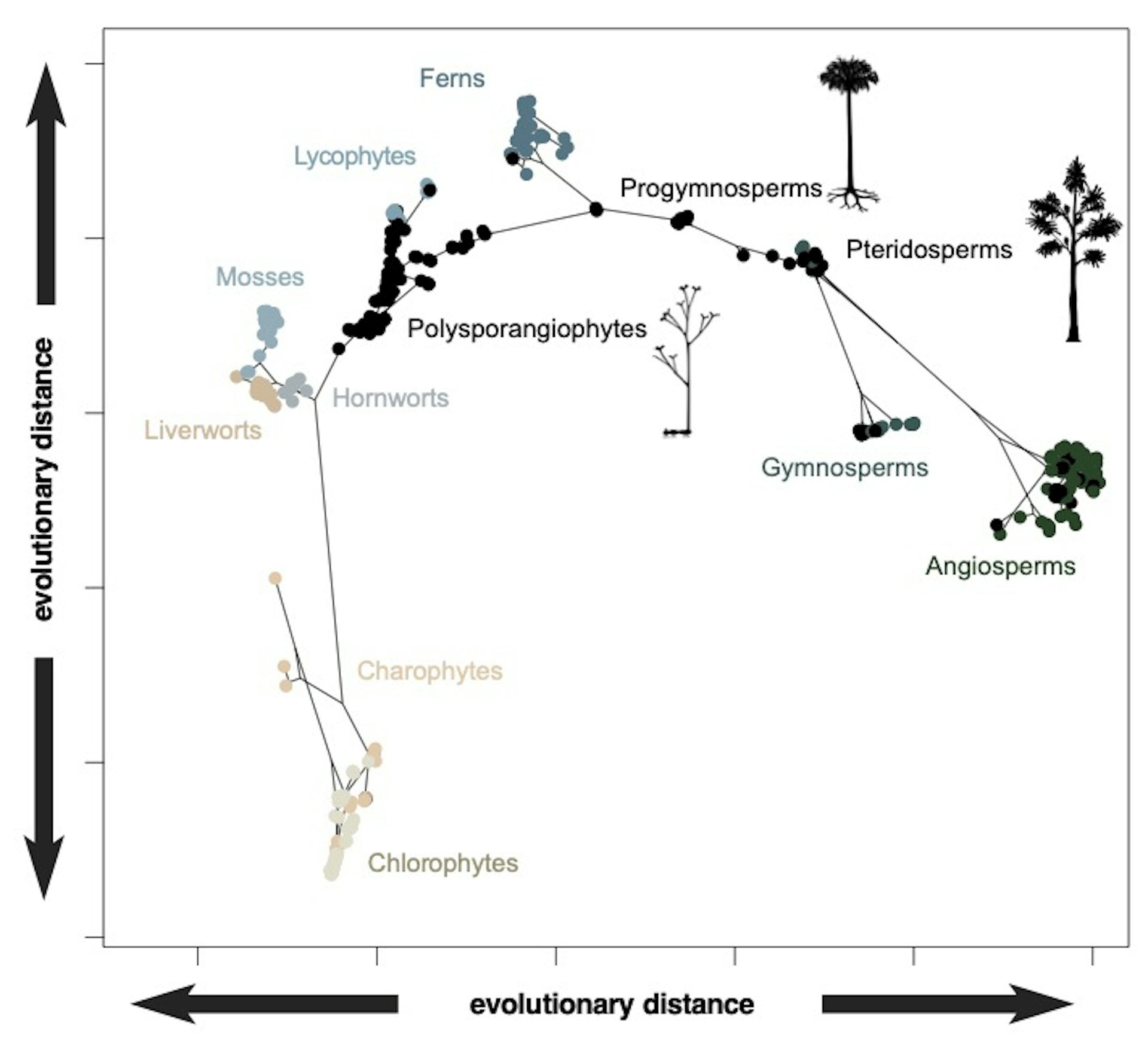

We then analysed all this data, grouping plants based on their overall similarities and differences, all plotted within what can be thought of as a “design space”. Since we know the evolutionary relationships between the species, we can also predict the traits of their extinct shared ancestors and include these hypothetical ancestors within the design space, too.

For example, we will never find fossils of the ancestral flowering plant, but we know from its closest living descendants that it was bisexual, radially symmetric, with more than five spirally arranged carpels (the ovule-bearing female reproductive part of a flower). Together, data points from living species, fossils and predicted ancestors reveal how plant life has navigated design space through evolutionary history and over geological time.

The two axes summarise the variation in anatomical design among plants. Coloured dots represent living groups while the black dots represent extinct groups known only from fossils. The lines connecting these groupings represent the evolutionary relationships among living and fossil groups, plus their ancestors, inferred from evolutionary modelling. (The chlorophytes and charophytes are marine and freshwater plants while the remaining groups are land plants. Angiosperms are flowering plants).

Philip Donoghue et al / Nature Plants

This may not be entirely surprising since the three lineages of bryophytes have been doing their own thing for more than three times as long as flowering plants. And despite their diminutive nature, even the humble mosses are extraordinarily complex and diverse when viewed through a microscope.

The evolutionary relationships conveyed by the branching genealogy in the above plot show that there is, generally, a structure to the occupation of design space – as new groups have emerged, they have expanded into new regions. However, there is some evidence for convergence, too, with some groups like the living gymnosperms (conifers and allies) and flowering plants plotting closer together than they do to their common ancestor.

Nevertheless, some of the distinctiveness of the different groupings in design space is clearly the result of extinction. This is clear if we consider the distribution of the fossil species (black dots in the above figure) that often occur between the clusters of living species (coloured dots in the figure).

So how did plant body plan diversity evolve?

Overall, the broad pattern is one of progressive exploration of new designs as a result of innovations that are usually associated with reproduction, like the embryo, spore, seed and flower. These represent the evolutionary solutions to the environmental challenges faced by plants in their progressive occupation of increasingly dry and challenging niches on the land surface. For example, the innovation of seeds allowed the plants that bear them to reproduce even in the absence of water.

Over geological time, these expansions occur as episodic pulses, associated with the emergence of these reproductive innovations. The drivers of plant anatomical evolution appear to be a combination of genomic potential and environmental opportunity.

Plant disparity suggests that the big bang is a bust

None of this fits with the expectation that evolutionary lineages start out innovative before becoming exhausted. Instead, it seems fundamental forms of plants have emerged hierarchically through evolutionary history, elaborating on the anatomical chassis inherited from their ancestors. They have not lost their capacity for innovation over the billion or more years of their evolutionary longevity.

So does that make plants different from animals, studies of which are the basis for the expectation of early evolutionary innovation and exhaustion? Not at all. Comparable studies that we have done on animals and fungi show that, when you study these multicellular kingdoms in their entirety, they all exhibit a pattern of episodically increasing anatomically variety. Individual lineages may soon exhaust themselves but, overall, the kingdoms keep on innovating.

This suggests a general pattern for evolutionary innovation in multicellular kingdoms and also that animals, fungi and plants still have plenty of evolutionary juice in their tanks. Let’s hope we’re still around to see what innovation arises next.

Philip C J Donoghue, Professor of Palaeobiology, University of Bristol; James Clark, Research Associate, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, and Sandy Hetherington, Plant Evolutionary Biologist, The University of Edinburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Technical details are given in the teams open access paper in Nature Plants:

AbstractCreationists will need to ignore the fact that the scientists who did this work interpret the results entirely in terms of the intelligently-designed theory of evolution, with no hint that it might not be adequate for the job.

The plant kingdom exhibits diverse bodyplans, from single-celled algae to complex multicellular land plants, but it is unclear how this phenotypic disparity was achieved. Here we show that the living divisions comprise discrete clusters within morphospace, separated largely by reproductive innovations, the extinction of evolutionary intermediates and lineage-specific evolution. Phenotypic complexity correlates not with disparity but with ploidy history, reflecting the role of genome duplication in plant macroevolution. Overall, the plant kingdom exhibits a pattern of episodically increasing disparity throughout its evolutionary history that mirrors the evolutionary floras and reflects ecological expansion facilitated by reproductive innovations. This pattern also parallels that seen in the animal and fungal kingdoms, suggesting a general pattern for the evolution of multicellular bodyplans.

Main

Biological diversity is not continuously variable but rather is composed of clusters of self-similar organisms that share a common bodyplan. Systematists have long exploited these discontinuities in the structure of biological diversity as a basis for imposing taxonomic order. However, the discontinuous nature of organismal design is intrinsically interesting, alternatively interpreted to reflect constraints in the nature of the evolutionary process, adaptive peaks or contingencies in evolutionary history. Much empirical work has shown that phenotypic diversity (disparity) is distributed unequally among lineages and across time, with many clades achieving maximal disparity early in their evolutionary history limited subsequently to expanding the range of variation within these early limits1,2. However, these observations have been based largely on studies of animal clades and it is unclear whether they are more generally applicable. Analyses of plant phenotypic disparity have focused on single groups of characters such as branching architecture3,4, reproductive organs5,6,7,8,9, leaf architecture or shape10,11 and vasculature12, and have been restricted to subclades or individual lineages13,14,15. Here we attempt an integrated characterization of the evolution of phenotypic disparity in the plant kingdom with the aim of testing the generality of macroevolutionary patterns observed in the animal kingdom.

They will also need to ignore the fact that all the evolutionary innovations that led to the major taxonomic groupings of plants all happened in the long period of Earth's history that preceded 'Creation Week', when, according the Bronze Age authors who put the legends into writing, the only plants mentioned were all flowering plants with not a single mention of algae, mosses or ferns. And, even more laughably, they were all created before the source of the photons they need for photosynthesis, the sun, was created. Clearly, whoever made up that tale knew nothing of photosynthesis, or the role sunlight plays in the lives of plants.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

How did you come to be here, now? This books takes you from the Big Bang to the evolution of modern humans and the history of human cultures, showing that science is an adventure of discovery and a source of limitless wonder, giving us richer and more rewarding appreciation of the phenomenal privilege of merely being alive and able to begin to understand it all.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.