A fossil of the winged-seed, Alasemenia, sourced from the Jianchuan mine in Xinhang Town, China.

Figure 1

Fertile branches and seeds of Alasemenia tria gen. et sp. nov.

(a) Thrice dichotomous branch with a terminal ovule. Arrow indicating boundary between ovule and ultimate axis (PKUB21721a). (b, f, g, i) Once dichotomous branch with a terminal ovule (PKUB21781, PKUB23132, PKUB19338a, PKUB17899). (c) Twice dichotomous branch with a terminal ovule (PKUB19713a). (d, e) Ovule with three integumentary wings (PKUB19321, PKUB19316). (h) Ovule showing two integumentary wings (PKUB19282). (j, k) Ovule terminating short ultimate axis (PKUB23114, PKUB23129). Scale bars, 1 cm (a–c, h), 5 mm (d–g, i–k).

The problem creationists have is that so much of Earth's history happened before their cult's dogma says it was created by magic just 10,000 years ago.

In fact, 99.9975% of Earth's history occurred during that long pre-'Creation Week' period, that just about any scientific paper dealing with fossils casually refutes creationism.

In fact the entire fossil record refutes creationism because nowhere in it are fossils found without ancestors and the geological column simply doesn't contain the evidence of a whole range of modern species suddenly appearing. It shows exactly the opposite - species evolving and diverging from common ancestors with modern forms having intermediate forms between them and common ancestors with other species in the same clade.

There is a clear progression in the fossil record of plants, for example, from simple single-celled algae, through primitive terrestrial mosses and liverworts followed by ferns, and eventually the angiosperms with their flowers and seeds.

Within the angiosperms there is again a fossil record or two main functions:

- Ferilisation of seeds, which included co-evolution between flowers and pollinators - bees, moths, birds, etc. - or wind pollination.

- Dispersal of seeds - wind, birds, mammals, etc.

And each of those fossil records is matched by the co-evolution of the pollinators and the seed dispersers.

Tell me about wind seed dispersal in plants, when it evolved, etc.

Wind seed dispersal, also known as anemochory, is a widespread adaptation in plants to ensure the spread of their seeds over large distances, increasing their chances of finding suitable environments for growth. This dispersal mechanism relies on wind to transport seeds that are often lightweight and have specialized structures to aid their movement through the air.

Key Features of Wind-Dispersed Seeds:

- Lightweight: Wind-dispersed seeds are typically small and light, allowing them to be carried long distances.

- Structures for Flight: Many of these seeds have adaptations like wings, hairs, or other structures that catch the wind. Examples include:

- Pappus: In species like dandelions (Taraxacum), the seed has a parachute-like structure called a pappus.

- Wings: In trees like maples (Acer), seeds have wing-like structures called samaras.

- Tumbleweeds: Some plants, like Salsola spp., disperse seeds by breaking off entirely and rolling in the wind.

Evolution of Wind Seed Dispersal:

Wind dispersal is a relatively ancient mechanism in plants, evolving as plants colonized terrestrial habitats. The earliest land plants likely relied on wind to disperse spores before the evolution of seeds. Once seeds evolved, various adaptations for wind dispersal followed. This trait has evolved independently across many plant lineages, making it an example of convergent evolution.

Some key evolutionary timelines include:

- Early Seed Plants: The gymnosperms, which appeared around 350 million years ago, often use wind for seed dispersal, as seen in conifers with winged seeds.

- Angiosperms: Flowering plants, which diversified during the Cretaceous (about 125 million years ago), also show multiple independent evolutions of wind dispersal traits. Many families of angiosperms, such as Asteraceae (the daisy family) and Poaceae (the grasses), have specialized wind-dispersal mechanisms.

Factors Driving the Evolution of Wind Dispersal:

- Open Habitats: Wind dispersal is particularly advantageous in open, windy environments such as grasslands, deserts, and mountainous regions.

- Resource Efficiency: Wind dispersal doesn't require the plant to invest energy in producing fleshy fruit to attract animals for seed dispersal, making it resource-efficient.

- Competition and Colonization: It allows plants to colonize new areas and reduce competition by spreading seeds far from the parent plant.

In conclusion, wind seed dispersal has evolved multiple times in both ancient and modern plant lineages, driven by the need to disperse seeds efficiently in open or windy environments. Its prevalence in diverse plant families highlights its evolutionary success.

And now a group of researchers have found the second-earliest known record of wind dispersal of seeds from roughly 360–385 million years ago, during the Late Devonian. The fossils were found in the Jianchuan mine in Xinhang Town, Anhui Province, China.

The team were led by Professor Deming Wang of the Key Laboratory of Orogenic Belts and Crustal Evolution, Department of Geology, Peking University, Beijing, China. Their findings are the subject of a paper in the on-line, open access journal,

eLife, and are explained in an eLife press release:

New seed fossil sheds light on wind dispersal in plants

Scientists have discovered one of the earliest examples of a winged seed, granting insight into the origin and early evolution of wind dispersal strategies in plants.

The study, published today as the final Version of Record after previously appearing as a Reviewed Preprint in eLife, details the second-earliest known winged seed – Alasemenia – from the Late Devonian epoch, roughly 360–385 million years ago. The authors use what the editors call solid mathematical analysis to demonstrate that Alasemenia’s three-winged seeds are more adapted to wind dispersal than one, two and four-winged seeds.

Wind dispersal in plant seeds is a natural mechanism that allows plants to spread their seeds through the air to new areas. This helps reduce competition for resources, increasing the plant’s chances of survival. Examples of wind dispersal strategies include tumbleweeds, parachutes such as dandelions and milkweeds, and winged seeds like those of the maple tree, often called ‘helicopter’ seeds.

The earliest-known plant seeds date back to the Late Devonian epoch.

This period marks a significant evolutionary milestone in plant history, as they transitioned from spore-based reproduction, as with ferns and mosses, to seed-based reproduction. However, little is known about wind dispersal in seeds during this time, as most fossils lack wings and are typically surrounded by a protective cupule.

Professor Deming Wang, lead author

Key Laboratory of Orogenic Belts and Crustal Evolution

Department of Geology

Peking University, Beijing, China.

Cupules are cup-shaped structures that partly enclose seeds, much like in acorns or chestnuts (although the Devonian cupules do not share the same origin with these modern ones), and could be associated with other dispersal methods, such as water transport.

To better understand early wind dispersal mechanism, Wang and colleagues studied several seed fossils from the Late Devonian, sourced from the Jianchuan mine in Xinhang Town, Anhui Province, China. From this, they identified a new fossil seed, Alasemenia.

They first described the characteristics of Alasemenia by carefully analysing the fossil samples, including making slices to view the seed’s internal structures. They found that Alasemenia seeds are about 25–33 mm long and clearly lack a cupule, unlike most other seeds of the period. In fact, this is one of the oldest-known records of a seed without a cupule, 40 million years earlier than previously believed. Each seed is covered by a layer of integument, or seed coat, which radiates outwards to form three wing-like lobes. These wings taper toward the tips and curve outward, creating broad, flattened structures that would have helped the seeds catch the wind.

The team then compared Alasemenia to the other known winged seeds from the Late Devonian: Warstenia and Guazia. Both of these seeds have four wings – Guazia’s being broad and flat, and Warstenia’s being short and straight. They performed a quantitative mathematical analysis to determine which seed had the most effective wind dispersal. This revealed that having an odd number of wings, as in Alasemenia, grants a more stable, high spin rate as the seeds descend from their branches, allowing them to catch the wind more effectively and therefore disperse further from the parent plant.

Our discovery of Alasemenia adds to our knowledge of the origins of wind dispersal strategies in early land plants. Combined with our previous knowledge of Guazia and Warsteinia, we conclude that winged seeds as a result of integument outgrowth emerged as the first form of wind dispersal strategy during the Late Devonian, before other methods such as parachutes or plumes.

Pu Huang, senior author

Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, China.

The three-winged seeds seen in Alasemenia during the Late Devonian would have subsequently been followed by two-winged seeds during the Carboniferous period, and then single-winged seeds during the Permian.

Professor Deming Wang.

Abstract

The ovules or seeds (fertilized ovules) with wings are widespread and especially important for wind dispersal. However, the earliest ovules in the Famennian of the Late Devonian are rarely known about the dispersal syndrome and usually surrounded by a cupule. From Xinhang, Anhui, China, we now report a new taxon of Famennian ovules, Alasemenia tria gen. et sp. nov. Each ovule of this taxon possesses three integumentary wings evidently extending outwards, folding inwards along abaxial side and enclosing most part of nucellus. The ovule is borne terminally on smooth dichotomous branches and lacks a cupule. Alasemenia suggests that the integuments of the earliest ovules without a cupule evolved functions in probable photosynthetic nutrition and wind dispersal. It indicates that the seed wing originated earlier than other wind dispersal mechanisms such as seed plume and pappus, and that three- or four-winged seeds were followed by seeds with less wings. Mathematical analysis shows that three-winged seeds are more adapted to wind dispersal than seeds with one, two or four wings under the same condition.

eLife assessment

This useful study describes the second earliest known winged ovule without a capule in the Famennian of Late Devonian. Using solid mathematical analysis, the authors demonstrate that three-winged seeds are more adapted to wind dispersal than one-, two- and four-winged seeds. The manuscript will help the scientific community to understand the origin and early evolutionary history of wind dispersal strategy of early land plants.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.92962.3.sa0

eLife digest

Many plants need seeds to reproduce. Seeds come in all shapes and sizes and often have extra features that help them disperse in the environment. For example, some seeds develop wings from seed coat as an outer layer, similar to fruits of sycamore trees that have two wings to help them glide in the wind.

The first seeds are thought to have evolved around 372-359 million years ago in a period known as the Famennian (belonging to the Late Devonian). Fossil records indicate that almost all these seeds were surrounded by an additional protective structure known as the cupule and did not have wings. To date, only two groups of Famennian seeds have been reported to bear wings or wing-like structures, and one of these groups did not have cupules. These Famennian seeds all had four wings.

Wang et al. examined fossils of seed plants collected in Anhui province, China, which date to the Famennian period. The team identified a new group of seed plants named the Alasemenia genus. The seeds of these plants each had three wings but no cupules. The seeds formed on branches that did not have any leaves, which indicates the seeds may have performed photosynthesis (the process by which plants generate energy from sunlight). Mathematical modelling suggested that these three-winged seeds were better adapted to being dispersed by the wind than other seeds with one, two or four wings.

These findings suggest that during the Famennian the outer layer of some seeds that lacked cupules evolved wings to help the seeds disperse in the wind. It also indicates that seeds with four or three wings evolved first, followed by other groups of seed plants with fewer seed wings. Future studies may find more winged seeds and further our understanding of their evolutionary roles in the early history of seed plants.

Introduction

Since plants colonized the land, wind dispersal (anemochory) became common with the seed wing representing a key dispersal strategy through geological history (Taylor et al., 2009; Ma, 2009.1; McLoughlin and Pott, 2019). Winged seeds evolved numerous times in many lineages of extinct and extant seed plants (spermatophytes) (Schenk, 2013; Stevenson et al., 2015). Lacking wings as integumentary outgrowths, the earliest ovules in the Famennian (372–359 million years ago [Ma], Late Devonian) rarely played a role in wind dispersal (Rowe, 1997). Furthermore, nearly all Famennian ovules are cupulate, i.e., borne in a protecting and pollinating cupule (Prestianni et al., 2013.1; Meyer-Berthaud et al., 2018).

Warsteinia was a Famennian ovule with four integumentary wings, but its attachment and cupule remain unknown (Rowe, 1997). Guazia was a Famennian ovule with four wings and it is terminally borne and acupulate (devoid of cupule) (Wang et al., 2022). This paper documents a new Famennian seed plant with ovule, Alasemenia tria gen. et sp. nov. It occurs in Jianchuan mine of China, where Xinhang fossil forest was discovered to comprise in situ lycopsid trees of Guangdedendron (Wang et al., 2019.1). The terminally borne ovules are three-winged and clearly acupulate, thus implying additional or novel functions of integument. Based on current fossil evidence and mathematical analysis, we discuss the evolution of winged seeds and compare the wind dispersal of seeds with different number of wings.

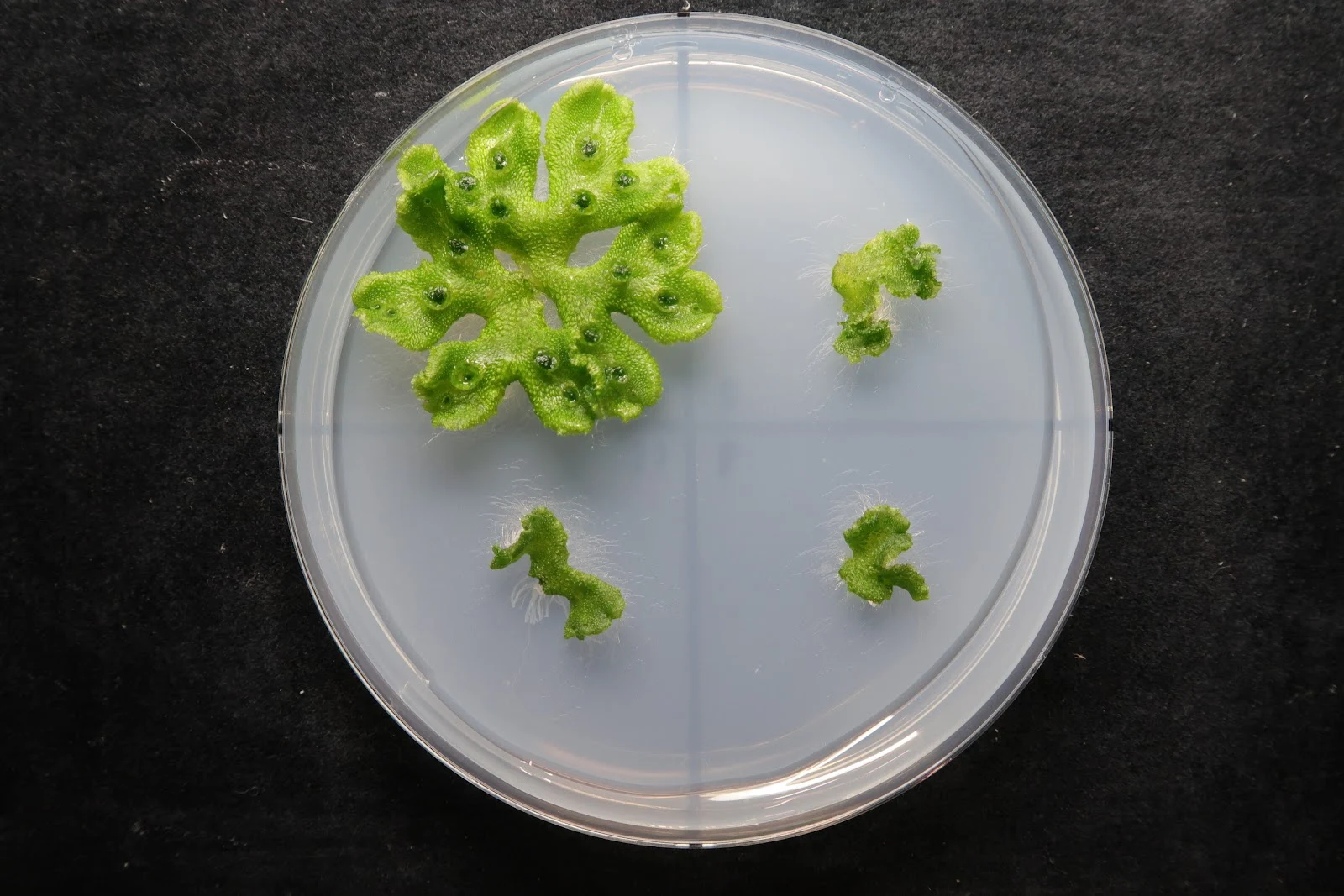

Figure 2

Fertile branches and seeds of Alasemenia tria gen. et sp. nov.

(a–c) Once dichotomous branch with a terminal ovule (PKUB16876a, b, PKUB17767). a, b, Part and counterpart. (d, e) Part and counterpart, arrow showing the third integumentary wing (PKUB19322a, b). (f) Ovule on ultimate axis (PKUB21752). (g, h, k–m) Ovules lacking ultimate axis (PKUB16788, PKUB21631, PKUB16522, PKUB21647, PKUB21656). (i, j) Part and counterpart, showing limit (arrows) between nucellus and integument (PKUB19339a, b). (n) Four detached ovules (arrows 1–4) (PKUB19331). (o) Enlarged ovule in n (arrow 2), showing three integumentary wings (arrows). Scale bars, 1 cm (n), 5 mm (a–h, k–m, o), 2 mm (i, j).

Figure 3

Seeds of Alasemenia tria gen. et sp. nov.

(a, b) Part and counterpart, enlarged ovule in Figure 1a (PKUB21721a, b). (c) Enlarged ovule in Figure 1c. (d) Counterpart of ovule in c (PKUB19713b). (e) Dégagement of ovule in d, exposing the base of the third integumentary wing (arrow). (f) Enlarged ovule in Figure 1d. (g, h) Enlarged ovule in Figure 2i and j, respectively. Scale bars, 5 mm (a–e), 2 mm (f–h).

Figure 4 with 5 supplements

Transverse sections of seeds of Alasemenia tria gen. et sp. nov.

(a, b) Part and counterpart. (c–e) Sections of seed in a and b (at three lines, in ascending orders). Arrow in d indicating probable nucellar tip (Slide PKUBC17913-12b, 10a, 9b). (f, g) Part and counterpart. (h–k) Sections of seed in f and g (at four lines, in ascending orders) (Slide PKUBC19798-8b, 6b, 4a, 4b). (l, m) Part and counterpart. (n–r) Sections of seed in l and m (at five lines, in ascending orders), showing three wings departing centrifugally (Slide PKUBC17835-5a, 7b, 8b, 9a, 10a). (s, v, A), One seed sectioned. (t, u) Sections of seed in s (at two lines, in ascending orders) (Slide PKUBC18716-8b, 7a). (w–z) Sections of seed in v (at four lines, in ascending orders) (Slide PKUBC20774-7a, 6b, 3a, 3b). (B–E) Sections of seed in A (at four lines, in ascending orders), showing three wings departing centrifugally (Slide PKUB17904-5b, 4a, 4b, 3b). Scale bars, 2 mm (a, b, f, g, l, m, s, v, A), 1 mm (c–e, h–k, n–r, t, u, w–z, B–E).

Figure 5

Reconstruction of two acupulate ovules with integumentary wings.

(

a)

Alasemenia tria with three wings distally extending outwards. (

b),

A. tria with one of three wings partly removed to show nucellar tip. (

c)

Guazia dongzhiensis with four wings distally extending inwards (Wang et al.,

2022). Scale bars, 5 mm.

And yet, despite this this daily refutation of creationism, the cult manages to stagger on, albeit shedding members as they reach the age of reason and realize they've neem fooled, and parasitic frauds like Ham and Kovind still cream off millions of dollars from their gullible and scientifically illiterate following in a desperate attempt to prove their inherited superstation gives them a better insight into the workings of the world around them than those clever-dicky, elitists scientists with their big words have.

Who needs facts and evidence, and all that bothersome learning when you have a mummy and daddy, and a preacher in a pulpit to tell you what to believe?