Scientists never set out to prove that the Biblical account of science and history as related in Genesis is hopelessly wrong and based on the childish guesses of scientifically illiterate people—that is simply an incidental outcome of the facts they revealed. Nevertheless, it remains a fact. The Bible presents a timeline and an account of the origin of species that are wholly inconsistent with the known facts.

To be fair to the original authors, they probably never intended to mislead scientifically illiterate people thousands of years later. As they devised origin myths to fill the gaps in their knowledge of the world, they could hardly have imagined that someone would one day write their tales down, combine them with other implausible myths, genealogies, and morality stories designed to spread fear and enhance priestly power, and then declare the compilation to be the inerrant word of an omniscient creator god. That declaration, of course, reinforced the text’s usefulness as a source of excuses for actions such as land theft, genocide, and enslavement—atrocities conveniently blamed on a god to absolve perpetrators of personal responsibility.

Mergansers (Mergus spp*) – Fish-Eating Specialists in Duck Evolution. Mergansers are a distinctive group within the duck family (Anatidae), best known for their long, slender, serrated bills adapted for catching fish. Unlike most ducks, which feed on plants or invertebrates, mergansers are specialist piscivores, and their anatomy reflects this ecological niche.They did their best with no scientific instruments and none of the fundamental principles of science that modern researchers take for granted. Scientific knowledge is cumulative, and the Bronze Age was simply too early in human history for much of it to have accumulated. The sad thing is that there are still parts of the world where scientific understanding is scarcely more advanced than it was then. For many, the Bible remains not a fascinating record of what people once thought and how they behaved before they knew better, but an inerrant sourcebook of genuine science and history.

Fossil and genetic evidence shows that mergansers diverged early within the diving duck lineage, representing a unique evolutionary experiment in exploiting fish as a primary food source. Ancient DNA, including samples from extinct island species such as the Chatham Island merganser (Mergus milleneri), provides valuable insights into how these birds dispersed across the globe. Their presence in places as remote as New Zealand demonstrates the remarkable flight capabilities of ancestral populations and their ability to colonise distant habitats.

Today, living mergansers are mainly found across the Northern Hemisphere, with species such as the common merganser (Mergus merganser), red-breasted merganser (M. serrator), and Brazilian merganser (M. octosetaceus). Their evolutionary history highlights both the adaptability of ducks as a whole and the vulnerability of specialised island forms, many of which have succumbed to extinction.

So it is against those solid rocks of fearful ignorance and superstition that wave after wave of scientific discovery breaks — yet the rocks remain stubbornly resistant and impervious to, or blissfully unaware of, the science engulfing them.

In my last blog post, I reported on a paper in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society of London and an article in The Conversation by four of its authors about an extinct shelduck from the Chatham Archipelago and what it could tell us about the evolutionary history of this group of ducks. Unsurprisingly, their findings utterly contradicted the Bible’s timeline and its naïve account of the spontaneous creation of species from nothing and without ancestors.

I now turn to an earlier paper by essentially the same research team, published in the same journal, this time accompanied by an article in The Conversation by two of its authors, Nic Rawlence, Senior Lecturer in Ancient DNA, University of Otago, and Alexander Verry, Researcher, Department of Zoology, University of Otago.

This study concerns the evolution of another group of ducks, the mergansers, Mergus spp. Once again, the researchers used DNA evidence—including that of an extinct member of the Chatham Island fauna, the Chatham Island merganser, M. milleneri — to build a picture of evolutionary history that utterly refutes the Bible’s timeline and creation myth.

The article in The Conversation is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Ancient DNA from an extinct native duck reveals how far birds flew to make New Zealand home

Auckland Island merganser. Artistic reconstruction by J. G. Keulemans

from Bullers Birds of New Zealand (1888)

from Bullers Birds of New Zealand (1888)

Bullers Birds of New Zealand, Author provided

Nic Rawlence, University of Otago and Alexander Verry, University of Otago

Ask a bird lover if they have heard of the extinct giant moa or its ancient predator, Haast’s eagle, and the answer will likely be yes. The same can’t be said of New Zealand’s extinct, but equally unique, mergansers – a group of fish-eating ducks with a serrated bill.

The only southern hemisphere representatives of this group are the critically endangered Brazilian merganser and those from the New Zealand region, which are now extinct.

Unlike some of New Zealand’s other extinct birds, the biological heritage of our enigmatic mergansers is shrouded in mystery. But our new research on the extinct Auckland Island merganser is changing the way we think about the origins of New Zealand’s birds. Did the ancestors of the merganser come from South America or the northern hemisphere – and when did they arrive?

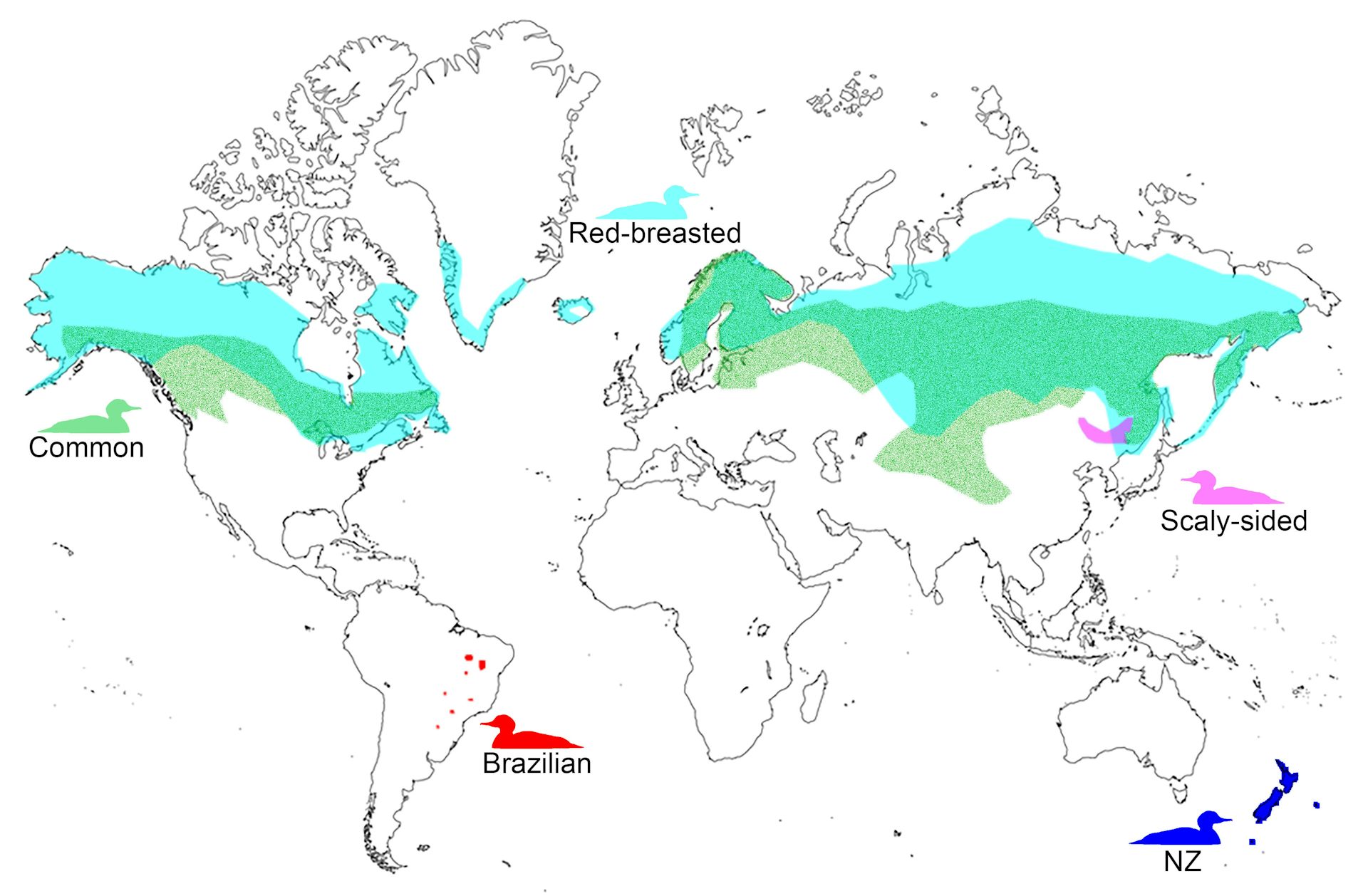

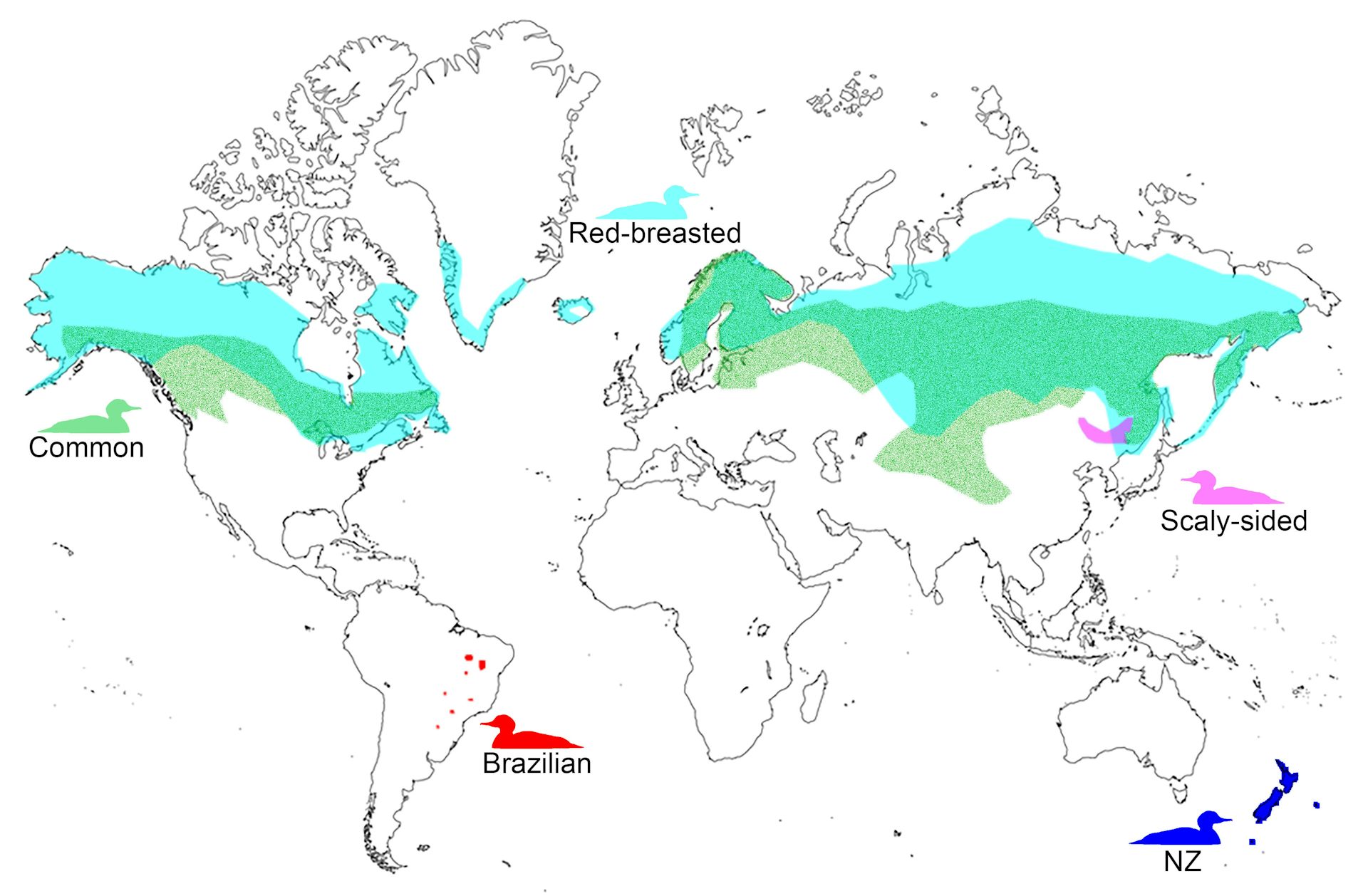

Mergansers are relatively common in the northern hemisphere but were limited to Brazil and the New Zealand region in the southern hemisphere.

Author provided

Lost to humans and pests

Mergansers were spread across the three main islands of New Zealand at the time of Polynesian arrival in the 13th century, as well as the Auckland Islands to the south and the Chatham Islands to the east.

Over-hunting, habitat destruction, and predation from the Pacific rat and Polynesian dog resulted in the extinction of mergansers on the New Zealand mainland and the Chatham Islands. By the time Europeans arrived in the 17th century, mergansers were restricted to an isolated population on the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands.

European discovery of the Auckland Islands in 1806 led to a formal description of the Auckland Island merganser in 1841. However, European discovery brought new predators like pigs and cats.

Mergansers were also sought after as specimens for the museum trade. The last known Auckland Island merganser was shot and collected in 1902, a mere 61 years after its discovery.

Auckland Island Merganser, Mergus australis, collected June 1902, Auckland Islands, New Zealand.

From the northern hemisphere to NZ

The extinction of mergansers from the New Zealand region has meant their evolutionary history has remained a mystery. Did their ancestors, and those of the Brazilian merganser, arrive via independent colonisation events from the northern hemisphere? Or was there a single push into the southern hemisphere, followed by subsequent divergence events?

To find out more, we sequenced ancient DNA from an Auckland Islands merganser and a Brazilian merganser. This allowed us to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the wider group.

We found mergansers originated in the northern hemisphere, diverging from their closest relatives some 18 million years ago, before rapidly evolving into several different species between 14 and seven million years ago.

The mergansers from the New Zealand region are most closely related to the northern hemisphere common merganser. Their ancestors arrived here at least seven million years ago in a separate colonisation event to the one that gave rise to the Brazilian merganser.

Further genetic research is currently underway. The goal is to reconstruct the evolutionary history of mergansers within the New Zealand region.

The global origins of New Zealand’s birds

Many New Zealanders believe the country’s native birds originate from Australia. Increasingly though, genetic and palaeontological research shows a number of our feathered friends hail from further afield.

Kiwi are most closely related to the extinct elephant birds of Madagascar, for example. And the extinct adzebill is related to flufftails, also from Madagascar. The extinct moa is most closely related to the tinamou from South America.

The long journey of blue-eyed shags started in South America, with the birds island hopping via Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic islands to New Zealand. Mergansers arriving from the northern hemisphere add another piece to the puzzle.

It is possible that fossils of extinct mergansers (and other birds with distant geographic origins) will be discovered as palaeontologists increasingly focus on previously neglected and newly discovered southern hemisphere fossil deposits.

Only then, combined with the power of ancient DNA, will we be able to fully understand how New Zealand’s dynamic geological, climatic and human history has influenced the colonisation and diversification of birds on this isolated South Pacific archipelago.

Nic Rawlence, Senior Lecturer in Ancient DNA, University of Otago and Alexander Verry, Researcher, Department of Zoology, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AbstractWhat emerges from studies such as these is not a deliberate attempt to undermine the mythology of Genesis, but the unavoidable consequence of revealing the facts. By tracing evolutionary histories through DNA evidence, palaeontology, and biogeography, scientists uncover stories written in the very fabric of life itself. These stories do not need embellishment or divine invention; they are written in molecules, fossils, and the patterns of distribution across the Earth.

Mergansers are riverine and coastal piscivorous ducks that are widespread throughout North America and Eurasia but uncommon in the Southern Hemisphere. One species occurs in South America and at least two extinct species are known from New Zealand. It has been proposed that these Southern Hemisphere merganser lineages were founded by at least two independent dispersal events from the Northern Hemisphere. However, some morphological and behavioural evidence suggests that Southern Hemisphere mergansers may form a monophyletic clade that descended from only a single dispersal event from the Northern Hemisphere. For example, Southern Hemisphere mergansers share several characteristics that differ from Northern Hemisphere mergansers (e.g. non-migratory vs. migratory, sexual monochromatism vs. sexual dichromatism, long vs. short pair bonds). We sequenced complete mitogenomes from the Brazilian merganser and an extinct merganser from New Zealand—the Auckland Island merganser. Our results show that the Brazilian and Auckland Island mergansers are not sister-taxa, and probably descend from two separate colonization events from the Northern Hemisphere at least 7 Mya. Nuclear (palaeo)genomic data may help to further resolve the relationship between living and extinct mergansers, including merganser fossils from New Zealand that have not been subjected to palaeogenetic analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Mergansers (Mergus spp.) are a group of riverine and seasonally coastal fish-eating ducks that have a widespread Northern Hemisphere distribution but are uncommon in the Southern Hemisphere (Kear 2005, Williams et al. 2012, 2014) (Fig. 1). They are characterized by a serrated bill, and include the endangered scaly-sided merganser (M. squamatus Gould 1864) from north-east Asia; the common merganser (M. merganser Linnaeus 1758), and the red-breasted merganser (M. serrator Linnaeus 1758), which have widespread Northern Hemisphere distributions; the critically endangered Brazilian merganser (M. octosetaceus Vieillot 1817); and two currently recognized extinct species from the New Zealand region—M. australis Hombron and Jacquinot 1841 and M. milleneri Williams and Tennyson 2014 from the Auckland and Chatham Islands, respectively. While the hooded merganser Lophodytes cucullatus (Linnaeus 1758), previously M. cucullatus, from North America has a serrated bill, it is not considered a ‘true’ merganser (e.g. Buckner et al. 2018, Lavretsky et al. 2021). The taxonomic relationship of the smew Mergellus albellus (Linnaeus 1758) from Eurasia is currently unresolved; it is sometimes suggested to be more closely related to Mergus and Lophodytes or to goldeneyes (Bucephala spp.) (Livezey 1995, Buckner et al. 2018, Lavretsky et al. 2021).

Schematic of the breeding distributions of Mergus spp. The New Zealand (NZ) lineage encompasses the Auckland Island merganser (465 km south of NZ) and Chatham Island merganser (785 km east of NZ), as well as Mergus spp. from mainland NZ. Breeding distributions are based off the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Birds of the World website.

Figure 1. Schematic of the breeding distributions of Mergus spp. The New Zealand (NZ) lineage encompasses the Auckland Island merganser (465 km south of NZ) and Chatham Island merganser (785 km east of NZ), as well as Mergus spp. from mainland NZ. Breeding distributions are based off the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Birds of the World website.

Figure 1. Schematic of the breeding distributions of Mergus spp. The New Zealand (NZ) lineage encompasses the Auckland Island merganser (465 km south of NZ) and Chatham Island merganser (785 km east of NZ), as well as Mergus spp. from mainland NZ. Breeding distributions are based off the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Birds of the World website.

The now extinct Auckland Island merganser M. australis (or miuweka) (Fig. 2) was formally described in 1841, based on a specimen collected on the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands, 465 km south of mainland New Zealand. Rare Late Holocene-aged merganser bones have been found in coastal sand dune deposits (including Māori middens) on New Zealand’s three main islands (Stewart, North, and South), and the Auckland and Chatham Islands (Tennyson and Martinson 2007, Williams et al. 2014, Tennyson 2020). Bones from the latter were recently described as a distinct species M. milleneri, which was smaller than the nominate M. australis, with a shorter skull, relatively shorter premaxilla, smaller sternum and keel, relatively shorter wing bones, and a narrower pelvis (Williams et al. 2014). The taxonomic status of merganser bones from mainland New Zealand is unresolved (i.e. cannot be assigned to either M. australis or M. milleneri), and are currently recognized as Mergus spp. (Birds New Zealand Checklist Committee 2022).

Figure 2. In the Southern Hemisphere, mergansers are only known from the New Zealand region and South America, represented here by the Auckland Island merganser. A, artistic reconstruction by J.G. Keulemans from Buller (1888); B, historical museum skin (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa OR.001357); C, the Brazilian merganser (photo by Savio Freire Bruno CC BY-SA 3.0).

Figure 2. In the Southern Hemisphere, mergansers are only known from the New Zealand region and South America, represented here by the Auckland Island merganser. A, artistic reconstruction by J.G. Keulemans from Buller (1888); B, historical museum skin (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa OR.001357); C, the Brazilian merganser (photo by Savio Freire Bruno CC BY-SA 3.0).

Mergansers in the New Zealand region are mainly thought to have occupied a riverine and seasonally coastal habitat (e.g. sheltered bays during winter; Kear 2005, Williams et al. 2012, 2014). It is likely that they mainly nested in tree cavities, but also caves in some instances, as the remains of adults, chicks, and eggs have been found within a cave on the Chatham Islands (Williams et al. 2014). By the 17th century, mergansers had been extirpated from the Chatham Islands and mainland New Zealand, and survived only on the Auckland Islands. A combination of subsistence hunting, and predation from the Pacific rat (Rattus exulans) and Polynesian dog (Canis familiaris), probably led to the extinction of mergansers across most of their prehistoric range (Tennyson and Martinson 2007, Greig and Rawlence 2021.1). On the Auckland Islands, predation from introduced pigs (Sus scrofa) and cats (Felis catus), and collecting for the museum trade, resulted in their extinction—indeed the last known Auckland Island merganser specimen was shot and collected in January 1902 (Williams 2012.1).

The only extant merganser in the Southern Hemisphere—the critically endangered Brazilian merganser (Fig. 2)—is one of the rarest birds in the world, comprising only 250 wild individuals. It is split across three remnant populations in Brazil, but once had a more widespread historical distribution encompassing Argentina and Paraguay (Vilaca et al. 2012.2, Maia et al. 2020.1). The Brazilian merganser has undergone a significant population bottleneck, yet different remnant populations can still be genetically identified (Maia et al. 2020.1). Like mergansers from the New Zealand region, the Brazilian merganser occupies riverine habitats, and often nests in tree cavities or rock crevasses (Vilaca et al. 2012.2, Maia et al. 2020.1).

It has been proposed that the Southern Hemisphere mergansers were founded by independent dispersal events to the New Zealand region and South America from the Northern Hemisphere (e.g. Livezey 1995). Based on behavioural characteristics, Johnsgard (1961) tentatively assigned the Brazilian merganser as sister-species to a clade comprising the other Mergus species, with the Auckland Island merganser as the sister-species of the common merganser and scaly-sided merganser. In contrast, using morphological characters, Livezey (1989, 1995) assigned the Auckland Island merganser, then Brazilian merganser, as successive sister-species to all other Mergus species, though with weak to moderate bootstrap support. Using mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences, Buckner et al. (2018) suggested the Brazilian merganser was the sister-species to the scaly-sided merganser, albeit with weak support. However, some evidence suggests that Southern Hemisphere mergansers may be closely related to one another, potentially even sister-species, as they share several behavioural (e.g. non-migratory and long pair bonds) and morphological (e.g. sexually monochromatic) characteristics, in contrast to their Northern Hemisphere congeners (e.g. migratory, short pair bonds, and sexual dichromatism; Livezey 1995). In addition, recent genetic studies of other extinct Southern Hemisphere avian species have also revealed unexpected evolutionary connections between birds from New Zealand, South America, and Africa (e.g. Mitchell et al. 2014.1a, [2014.2]b, Boast et al. 2019, Rawlence et al. 2022.1, Verry et al. 2022.2a). As such, the phylogenetic relationships of the Southern Hemisphere mergansers, when their ancestors arrived in the region, and from where, remain unresolved.

In this study, the first genetic study of a New Zealand Mergus species, we sequenced mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) from historical museum specimens from the Auckland Island merganser and Brazilian merganser, and analysed them within a phylogenetic framework of Mergini mitogenomes (Liu et al. 2012.3, Lavretsky et al. 2021). These data were used to determine the phylogenetic relationships and divergence dates within mergansers.

The Biblical account, by contrast, rests on the imaginative guesses of ancient people without access to any of the tools or accumulated knowledge of science. It offers a static, unchanging picture of creation, in which each species was conjured into existence in its final form, without history or connection. The discoveries of modern science render this picture untenable, not because scientists set out to disprove it, but because the evidence paints a richer and more coherent story—one in which change, adaptation, migration, and extinction are the central themes.

In that sense, every new piece of research into evolutionary history is another wave breaking against the rock of ignorance and superstition. The rock may stand defiant, weathered but unyielding in places, yet the tide of knowledge never ceases. With each advance in ancient DNA analysis, each fossil unearthed, and each lineage mapped, the Biblical narrative is left further behind as nothing more than an obsolete myth, fascinating for what it tells us about human imagination in the Bronze Age, but utterly irrelevant to understanding the living world today.

Advertisement

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

How did you come to be here, now? This books takes you from the Big Bang to the evolution of modern humans and the history of human cultures, showing that science is an adventure of discovery and a source of limitless wonder, giving us richer and more rewarding appreciation of the phenomenal privilege of merely being alive and able to begin to understand it all.

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

All titles available in paperback, hardcover, ebook for Kindle and audio format.

Prices correct at time of publication. for current prices.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.