|

| Tudor 'Plantations' in Ireland |

Part 2 of a History of Ireland

Tudors.

Soon there was a new line of English monarchs with new ideas of a modern, centrally controlled nation state. They were determined that the anarchy of Ireland was to end. In 1515 Ireland was described as:More than sixty counties called regions inhabited by the King’s Irish enemies... where reigneth more than sixty chief captains wherein some call themselves Kings, some Princes, some Dukes, some Archdukes that liveth only by the sword and obeyeth unto no temporal person... and every of the said captains maketh war and peace for himself... And there be thirty great captains of the English folk that follow the same Irish order... and every of them maketh war and peace for himself without any licence of the King...

In 1534, Henry VIII decided to put an end to this intolerable state of affairs. The House of Fitzgerald, earls of Kildare, and nominally representing the English Crown, was in open rebellion. Henry decreed that all lands in Ireland were to be surrendered to the Crown and then re-granted. His daughter, Elizabeth I, was to enforce this new control with a ruthless severity.

The effect of this was that the Gaelic chiefs no longer held land according to Gaelic Law but by the King’s Law and the King’s good will. The Irish were described by one contemporary writer thus:

The Irish live like beasts... are more uncivil, more uncleanly, more barbarous in their customs and demeanours than in any part of the world that is known.

A missionary zeal to civilise pervaded English society and Ireland was seen as a wild land to be tamed, much as the Spanish saw the New World. They were no less ruthless. Elizabeth herself wrote:

"We perceive that when occasion doth present you do rather allure and bring in that rude and barbarous nation to civility by discreet handling rather than by force and shedding of blood; yet when necessity requireth you are ready to oppose yourself and your forces to those whom reason cannot bridle."

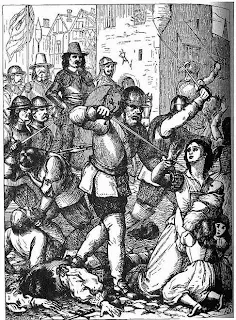

Necessity required force to be used often it seems, and it was applied with frequent and unprecedented savagery by a largely English soldiery. Sir Henry Sidney, one of Elizabeth’s deputies, wrote:

I write not to your honour the name of each particular varlet that hath died since I arrived, as well by the ordinary course of law, and martial law as flat fighting with them... but I do assure you, the number of them is great, and some of the best, and the rest do tremble for the most part... Down they go in every corner and down they shall go...

It was said of Sir Humphrey Gilbert, another of Elizabeth’s deputies:

His manner was that every head of all those which were killed in the day should be cut from their bodies and brought to the place where he encamped at night, and should be there laid on the ground by each side of the way leading to his own tent, so that none should come unto his tent for any case but commonly he must pass through a lane of heads, which he used ad terrorem – the dead feeling nothing the more pains thereby. And yet it did bring a great terror to the people when they saw the heads of their dead fathers, brothers, children, kinsfolk and friends lie on the ground before their faces...

So the foundations for the traditional hatred of the Irish for the governing English were lain.

The common resentment for the new English rulers spurred on the process of assimilation between the Irish and the Old English (the Anglo-Irish), but it was religious differences that were finally to complete the process.

The Protestant Reformation utterly failed to make any real inroad in terms of converts amongst the Irish for two reasons:

- Most of Ireland was simply too remote and inaccessible for England to impose a new religion as well as a new order. The Catholic Church was unassailable behind a landscape of bog and scrub in a land of few roads. The fact of the hates enemy having a different religion strengthened the Catholic Church rather than weakened it.

- For political reasons, Elizabeth had no wish to antagonise Spain still further by outright repression of the Catholic Church in Ireland, and forcibly converting its followers to Protestantism. Though nominally part of the Protestant Reformation, the Irish were almost completely untouched by it.

|

| Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone |

He formed an alliance with another Ulster Gaelic chief, Hugh O’Donnell, and almost succeeded a few miles north of Armagh in 1598 at Yellow Ford where he defeated an English army. However, Tyrone was not fighting for Ireland; he was fighting for himself in the great tradition of Irish chiefs. A Spanish fleet was sent to Ireland to help him and it anchored in the south off Kinsale. Mountjoy, the Protestant deputy, marched south and laid siege to the Spanish in Kinsale, and Tyrone and O’Donnell marched south to lay siege to the English in turn. It resulted in the final battle for Gaelic Ireland. Tyrone made the mistake of attacking the English in the open. His soldiers, whose special skills were more appropriate to fighting in bogs, were routed and scattered north in disorder. Tyrone submitted to the Crown and obtained a pardon, much to the fury of the English administrators of Ireland.

At the end of the Tudor period, Ireland had, for the first time in its history, a centralised government and the appearance of a nation state, albeit within the English State. However, its people now had a common enemy and a unique identity. An identity reinforced by a different religion, which had become an integral part of this political identity. The Gael were Catholic Irish; they were determinedly not Protestant English.

Plantations.

Such are the thin threads of history that the Gaelic rebellion of Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell led, in a roundabout way, to the present troubles in Northern Ireland and to Protestants there insisting on a separate identity, a distinct way of life, and the right to march triumphantly through predominantly Catholic areas wearing orange sashes and bowler hats.Hugh O’Niell was allowed to remain in Ulster under the watchful eye of English officials infuriated by his pardon. They plotted against him, falsely accusing him of treason and fining him for practicing his Catholic religion, and insisted he run his province according to English Law, not Gaelic Law as he wished. Finally, in fear of his life, he and O’Donnell's heir, Rory, the Earl of Tyrconnell, took flight in a French ship from Rathmullen, on 4 September 1607. This lent credence to the stories of treason and Tyrone’s and Tyrconnell’s land were forfeited to the Crown.

The ‘Flight of the Earls’ has huge symbolic significance for the Gaelic Irish as it represents the banishment of the last of the line of ancient Gaelic tribal leaders from Irish soil. That it was quickly followed by colonisation by non-Irish people gives it special poignancy.

The Crown so acquired the four counties of Donegal, Tyrone, Derry and Armagh, and they, together with the counties of Cavan and Fermanagh became subjected to the most systematic attempts yet to plant Protestants from England and Scotland. This was the ‘Plantation of Ulster’ which had been worked out on a government drawing board between 1608 and 1610.

|

| Protestant Plantations in Ireland |

The ‘Irish Society’ was formed and, in 1610, it was given responsibility for colonising the forfeited lands of the flown earls in the same way that the Virginia Society was colonising North America. It was the Irish Society, which exists to this day and has an office close to Derry Cathedral, which changed the name of Derry to Londonderry. The land was divided between the London liveried companies – drapers, salters, fishmongers, haberdashers, etc. The plan was to apportion eighty-five percent of the land, via these companies, to English and Scottish settlers who would not be allowed to take Irish tenants. Five percent was to go to former soldiers who were allowed to take Irish tenants, in effect becoming a new middle-class of landlords, and the other ten percent was to go to native Irish. These former owners of the whole land now had to pay double the rent that the settlers paid and they got the least fertile land.

|

| Land Distribution |

The result of this was a Gaelic population that remains numerically strong, yet was embittered and resentful, and a Protestant minority which felt insecure and beleaguered but believing in its cultural superiority and its right to be masters in its new home. The settlers forfeited their farms for security against the dangers that lurked in the woods and bogs outside their windows, fearful of the 3000 former bowmen of the flown earls who were reputed to inhabit the woods and bogs and other wild places of remote Ulster.

|

| Ulster Population by Religion |

The success of the eastern settlement meant that the majority of settlers were Scot and Presbyterian rather than Anglican, and, when they first arrived, they were penalised by the Anglican Church as dissenters. It is a matter of record that, on one Sunday alone, 500 Presbyterian crossed to Stranraer in Scotland to receive the sacrament in a way forbidden to them in Ulster.

So developed the traditional independence of spirit in Ulster’s Protestant culture. Not Irish, not English and not Scot. They became Ulster men and women. They became the standard-bearers of the ‘true faith’ beset by enemies. They were alone and isolated in a hostile land, and they had no one to turn to but themselves. Their worst fears were realised on 23 September 1641 when the Gaelic Irish Catholics rebelled.