Jujube, Ziziphus jujuba.

Source: Alex___photo/Shutterstock

Although Creationists seem to be baffled by the concept of uncertainty and the idea that knowledge can only ever be provisional, in fact, this is what gives science it's great power. By contrast, religions, which depend on certainty in the face of a lack of evidence and where a 'crisis of faith', i.e., doubt due to an unwelcome intrusion of reality, is considered a bad thing, are still mired in the Bronze Age when the basic ideas were first codified by people who knew little but sought certainty in a confusing and frightening, seemingly magical world, so made some best guesses with what little knowledge they had.

So, it's never surprising and always reassuring when another science paper is published showing that the scientific consensus was wrong about something. Unlike with black and white Creationists thinking, right and wrong are not absolute terms in science. Scientific ideas can be mostly right but not absolutely right since there are no absolutes where there is uncertainty and without uncertainty there is no scientific progress. Rather, science is a self-correcting, ever improving search for the truth as revealed by evidence.

As we say, science is reasonable uncertainty, whereas religion is unreasonable certainty.

The paper which suggests we need to change our minds is about the timing of the earliest appearance of flowering plants on Earth. Note that we were not wrong in the sense that flowering plants didn't evolve from earlier vascular plants such as ferns; the 'mistake' was in thinking it happened some 150 million years earlier than we now know. A mistake in the fine detail of the timing, not in the facts themselves.

Sadly, the paper in Trends in Plant Science is behind an expensive paywall, despite the journal's claim to support open access. However, the lead author, Professor Byron Lamont, Distinguished Professor Emeritus in Plant Ecology, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia, has written an open access article in The Conversation describing his research with co-author, Tianhua He, of the College of Science, Health, Engineering and Education, Murdoch University, Murdoch, WA, Australia. It is reprinted here under a Creative commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency.

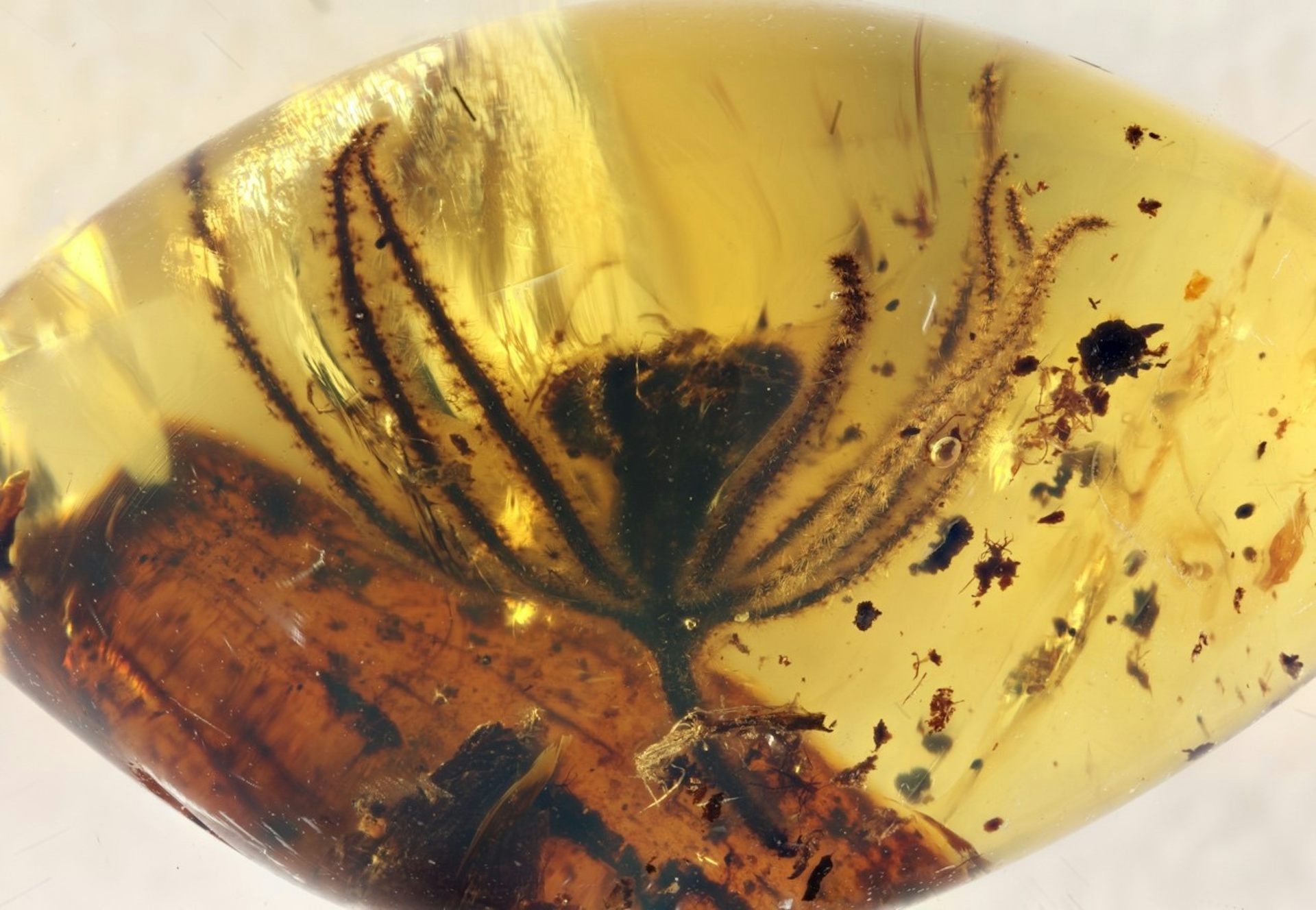

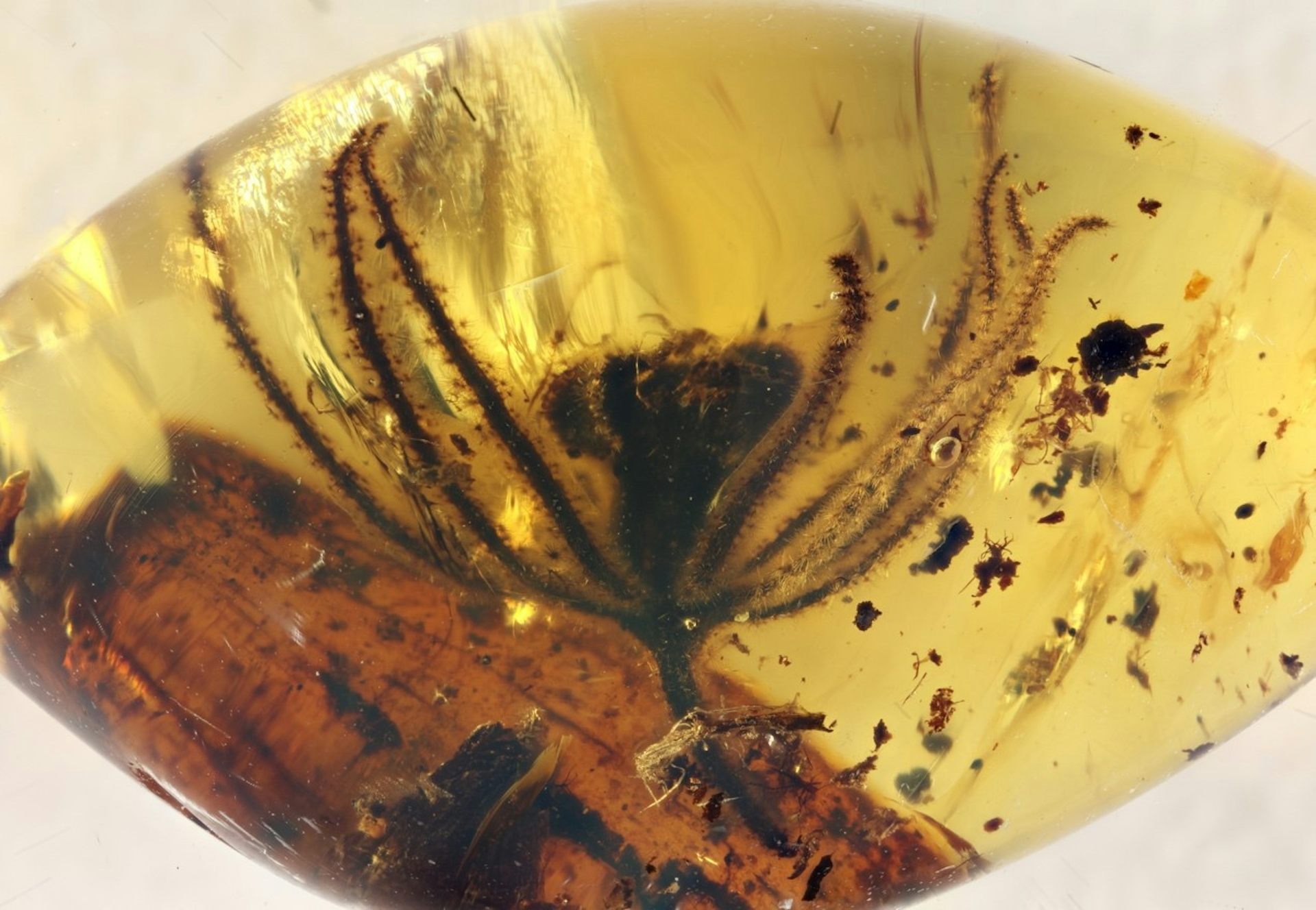

Professor Lamont takes as his starting point, a 2022 paper, published by Shi et al, in Nature Plants (sadly also behind an expensive paywall) which reports finding "two exquisitely preserved fossil flower species, one identical to the inflorescences of the extant crown-eudicot genus Phylica and the other recovered as a sister group to Phylica, both preserved as inclusions together with burned plant remains in Cretaceous amber from northern Myanmar (~99 million years ago)". Obviously, this takes some explaining because it is earlier than formerly believed and the Phylica genus is also found in South America.

Professor Lamont's original article can be read here.

A new discovery shows major flowering plants are 150 million years older than previously thought

Credit: Prof Shuo Wang/Shi et al., 2022, Author provided

Byron Lamont, Curtin University

A major group of flowering plants that are still around today, emerged 150 million years earlier than previously thought, according to a new study published today in Trends in Plant Science. This means flowering plants were around some 50 million years before the dinosaurs.

The plants in question are known as the buckthorn family or Rhamnaceae, a group of trees, shrubs and vines found worldwide. The finding comes from subjecting data on 100-million-year old flowers to powerful molecular clock techniques – as a result, we now know Rhamnaceae arose more than 250 million years ago.

A widespread family

Today, the buckthorn family of shrubs is widespread throughout Africa, Australia, North and South America, Asia and Europe. The important fruit jujube or Chinese date belongs to the Rhamnaceae; other species are used in ornamental horticulture, as sources of medicine, timber and dyes, and to add nitrogen to the soil.

Flowering shoots of the shrub Phylica, now confined to South Africa, have recently been found in amber from Myanmar that is more than 100 million years old.

Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba) belongs to the buckthorn family.

Source: Alex___photo/Shutterstock

We did this by comparing the DNA of living plants of Phylica against the rate of DNA change over the past 120 million years, to set the molecular clock for the rest of the family.

This Phylica flower was trapped in tree sap along with some charcoal over 100 million years ago. Time has turned it to amber.

Prof Shuo Wang/Shi et al. 2022, Author provided

Older than we could have imagined

It was previously believed that Phylica evolved about 20 million years ago and Rhamnaceae about 100 million years ago, so these new dates are much older than botanists could possibly have imagined. Since Rhamnaceae is not even considered an old member of the flowering plants, this means flowering plants arose more than 300 million years ago – some 50 million years before the rise of the dinosaurs.

Phylica pubescens, also known as featherhead.

Molly NZ/Shutterstock

But how did Phylica get from the Cape of South Africa to Myanmar? Our data on the history of the plant’s evolution show the most likely path is that Phylica migrated to Madagascar, then to the far north of India (most of which is under the Himalayas now), all of which were joined 120 million years ago.

India then separated and drifted north until it collided with Asia. The far northeast section, known as the Burma tectonic plate, became Myanmar about 60 million years ago. Sap, possibly released by fire-injured conifers, flowed over the Phylica flowers and preserved them intact as amber while India was still attached to Madagascar.

Forged in fires

In fact, the vegetation in which Rhamnaceae evolved was probably subjected to regular fires. The first clue was the charcoal researchers have found together with the Phylica fossils in the amber.

The second is that today, almost all living species in the Phylica subfamily have hard seeds that require fire to stimulate them to germinate.

I assessed the fire-related traits of as many living species as possible, then He traced them onto the evolutionary tree he had created, using a technique called ancestral trait assignment. This showed there was a strong possibility the earliest Rhamnaceae ancestor was fire-prone and produced hard seeds.

We have extensively studied the evolutionary fire history of banksias, which go back 65 million years, along with proteas, pines, wire rushes and the kangaroo paw family.

Our new results make the buckthorn family of plants by far the oldest to show fire-related traits of all the plants we have studied over the past 12 years.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.