Geosiris australiensis

Source: Grey & Lee (2017)

Readers may remember how I recently described one of the most important symbiotic relationships on Earth - that between trees and fungi - as a classic example of how cooperation can evolve by the interaction of 'selfish' genes with other genes in their environment.

Creationists looking at that same relationship will insist that it is evidence of intelligent [sic] design, without ever providing evidence that such a designer entity has ever existed, any plausible mechanism by which it could have arisen without a designer, or a single, authenticated example of it ever having made chemistry and/or physics do something they couldn’t do without it.

Nevertheless, despite these shortcomings of their superstition, which means it isn't even a theory in the scientific sense, it satisfies their desire for easy answers, conforms with what their mummy and daddy believed, and avoids all that tiresome learning. Their conclusion is, therefore, that it must be true because it passes their "What do I want to be true?" test.

This article then will spoil that smugly self-satisfying conclusion on at least three counts:

- It shows any designer of this example to be a malevolent cheat who favours free-loading parasites.

- It involves evolution by loss of genes - something Creationist dogma claims is impossible in the erroneous belief that loss of information and loss of complexity are always deleterious, even though they are commonplace in successful parasites.

- It involves plate tectonics and an old Earth to explain how this example from Australia is related to species from Madagascar and the Comoro Islands.

Those Creationists who are afraid of even considering whether they could be wrong in case they upset an invisible, mind-reading, magic sky man, should probably stop reading now.

The following article by Elizabeth Joyce of James Cook University, Australia, reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency, concerns a recently-discovered Australian parasitic plant that freeloads on the symbiotic relationship between fungi and plants by stealing the nutrients from the photosynthetic plant but giving nothing back. The original article can be read here:

Geosiris is an early contender for Sexiest Plant of 2019

Geosiris australiensis

Credit: The Conversation/THawkes

Elizabeth Joyce, James Cook University

Sign up to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian.

It’s a pale rebel with a mysterious past, who doesn’t play by the family rules. You might not guess from looking at it, but Geosiris australiensis is my pick for the Sexiest Plant of 2019.

I might be biased though: my colleagues and I have just uncovered the amazing life, and evolutionary history of this mysterious herb. It was only found in Australia in 2017, so there’s plenty left to discover.

But here are five things we do know about this strange, alluring guy.

You’re no sun of mine!

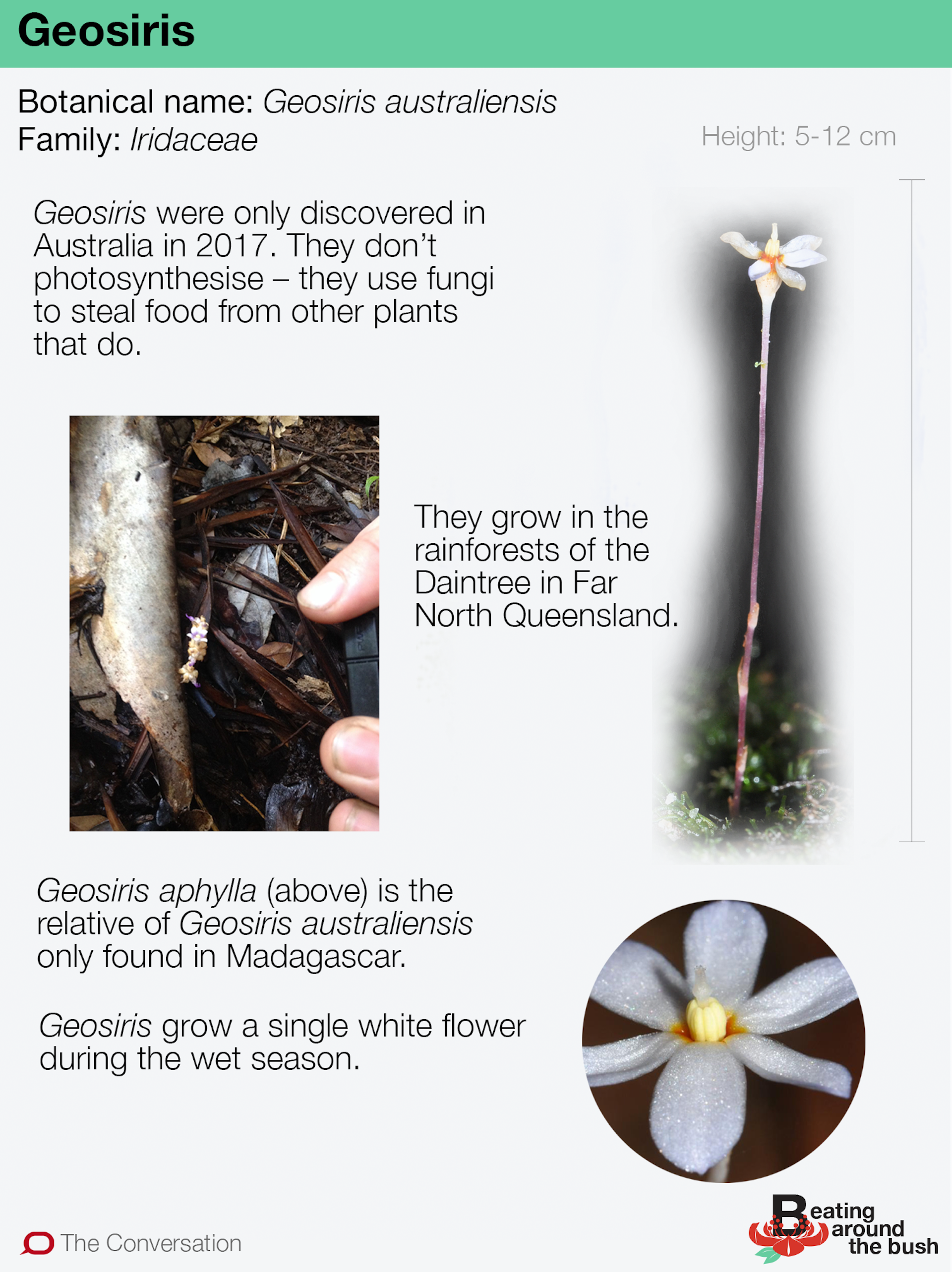

Geosiris (literally, “earth iris”) grow as small (5-12 cm high), pale, perennial herbs on the floor of the tropical rainforest. A single stem arises from an underground rhizome which produces a white or pale purple flower after every wet season.

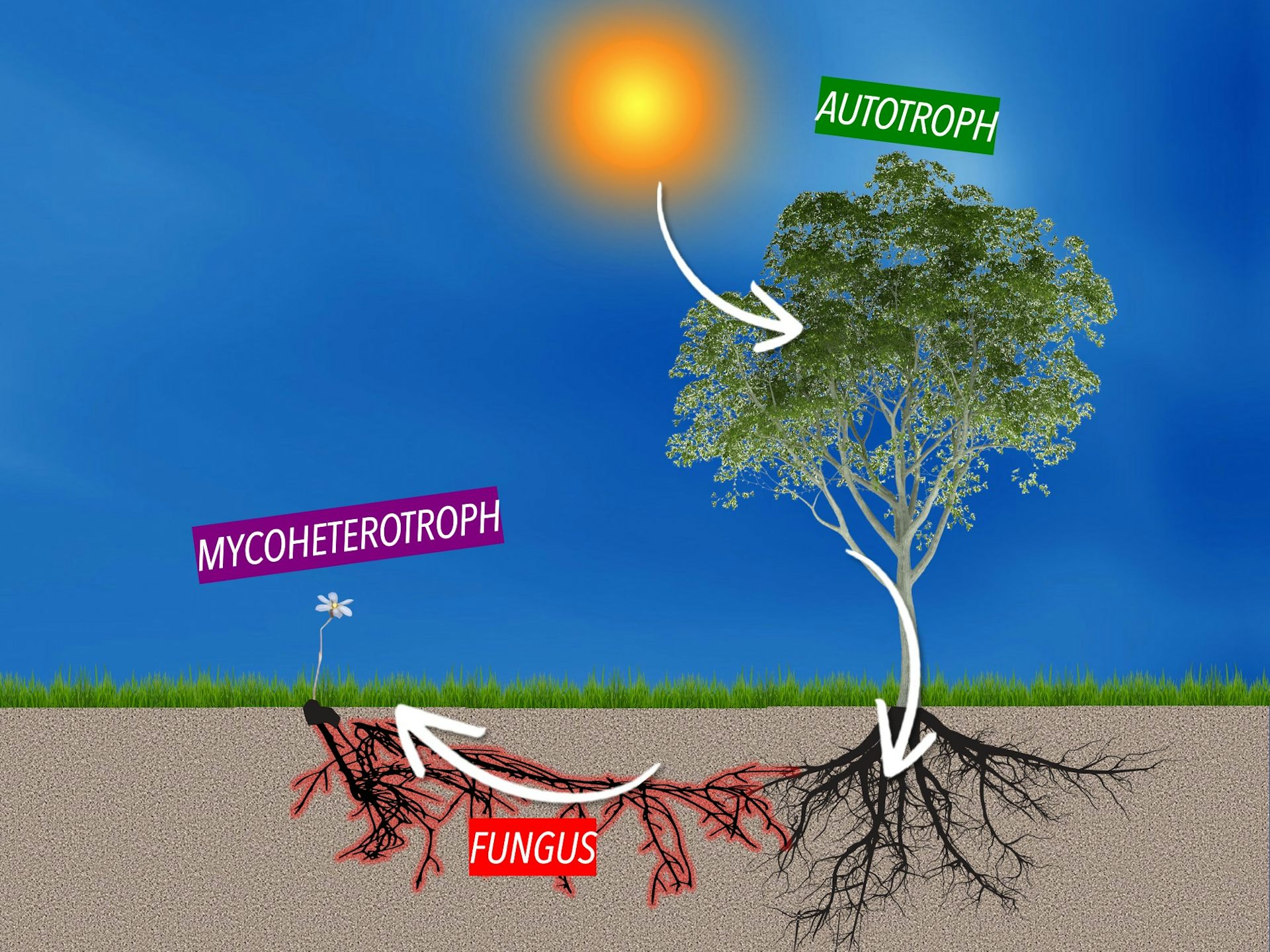

Geosiris doesn’t photosynthesise. Most plants are autotrophic (auto = self, trophic = feeding) – that is, they make their own food using energy from the sun through photosynthesis. Plants photosynthesise by using green chlorophyll, stored in part of the cell known as a chloroplast.

However Geosiris is mycoheterotrophic (myco = fungus, hetero = other, trophic = feeding). Instead of photosynthesising, it steals the food from autotrophic plants and uses fungi as the middle man. That is why Geosiris isn’t green: it doesn’t photosynthesise so there is no green chlorophyll.

So how does Geosiris get away with this? It’s unclear, but our best guess is that Geosiris has found a way to cheat an already well-established system.

More than 90% of all plants have a cooperative relationship with fungi in the soil, in which the fungus offers up soil nutrients (such as phosphorus) to the plant in exchange for carbon. However, when plants evolve mycoheterotrophy, they work out a way of hijacking this system: mycoheterotrophs take nutrients from the fungus as well as the carbon it harvested from the photosynthesising plant.

This relationship is thought to be very specialised, with specific mycoheterotroph, autotroph and fungus species involved in each interaction. We think this is what Geosiris does, but much more research is needed into how it gets away with such a scandal, what’s in it for the fungus, and what species of fungus is involved.

The sun feeds most plants, and Geosiris steals from them using fungal associations.

Credit: Author provided

They’re the family rebel…

Mycoheterotrophy is surprisingly common in plants. Occurring in more than 500 species of flowering plants, this stealthy feeding strategy has evolved at least 47 separate times in 36 plant families, one species of liverwort, and (possibly) one conifer.

However, Geosiris earns its rebel status by being the only mycoheterotrophic genus in its family, Iridaceae, which contains many popular garden genera such as Iris, Gladiolus, Freesia and Dietes.

Geosiris split off from its autotrophic ancestors about 53 million years ago. During this time away from the family, Geosiris did away with photosynthesis and became mycoheterotrophic.

…with a sexy, slimmed-down genome

This loss of photosynthesis was accompanied by a major change in the genes of Geosiris. Genes responsible for photosynthesis are found in the chloroplast genome. The chloroplast genome mostly contains genes responsible for photosynthesis, however also contains a few genes important for processes like energy production.

Over the past 53 million years, the number of functional genes in the Geosiris chloroplast genome has roughly halved compared with its autotrophic relative Iris missouriensis. This reduction in number of genes is not random though. The genes lost were those responsible for photosynthesis, while the genes retained have vital functions like energy production that Geosiris still needs.

Think of it like a Fitbit. You buy one with the intention of seeing your New Year fitness resolutions through, but come March your exercise regime falls by the wayside. In the meantime your Fitbit stops working but you don’t mind: you’re not using it anymore so there is no need to get it fixed. Eventually that Fitbit ends up in the bottom of your drawer, lost forever along with sundry cables, batteries and the SoFresh Greatest Hits of 2010.

In the case of Geosiris, over time photosynthetic genes become mutated but the cell doesn’t bother to fix the mutated genes because they aren’t needed. These gene mutations are passed on to offspring, and over generations the genes are eventually lost forever.

They’re rare…

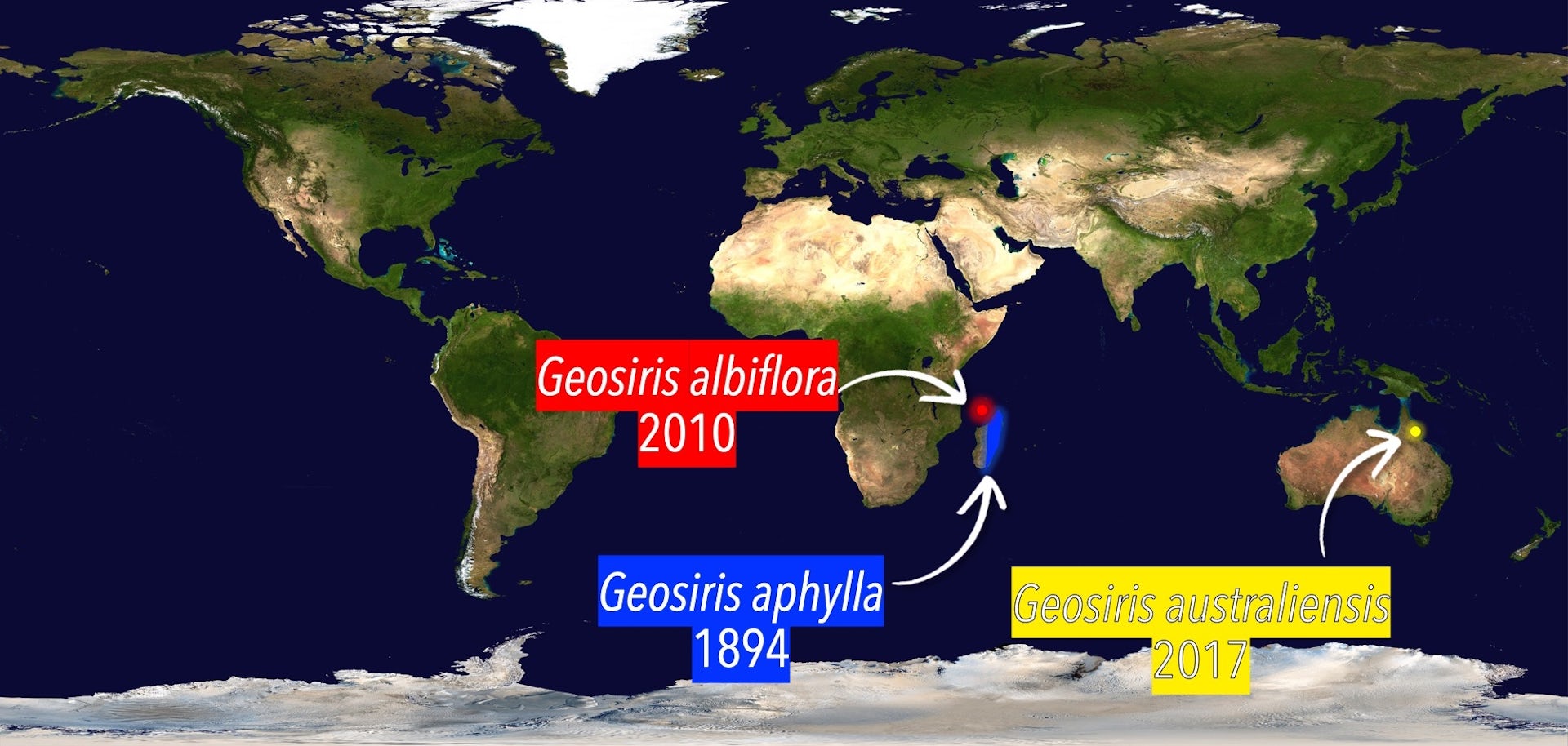

For more than 100 years, there was only one species of Geosiris known to science: Geosiris aphylla from the rainforests of Madagascar. It wasn’t until 2010 that a second species was discovered in the Comoro Islands, just north of Madagascar. But then, in 2017 botanists on an expedition discovered a new species_ – Geosiris australiensis - in the Daintree Rainforest of Queensland, Australia.

So how did such a small, mycoheterotrophic herb find its way across the vast Indian Ocean?

…and glamorous globe-trotters

The Iridaceae family originated in Australia (back when Australia was still connected to Antarctica), but around 53 million years ago the ancestor of Geosiris travelled across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar. Then, around 30 million years ago, a lineage of Geosiris managed to travel back to Australia, splitting off into the newly discovered species Geosiris australiensis.

There are a few explanations as to how the ancestors of Geosiris did so much travelling in a time before Qantas frequent flyer points. One is that they did, literally, jump across the Indian Ocean, with seeds carried by wind between Madagascar and Australia. Geosiris has minuscule “dust seeds”, only about 0.2 millimetres wide. They’re so small they can be carried by wind for long distances. Records show that similar dust seeds from orchids have been carried thousands of kilometres by wind dispersal.

A second, more likely explanation, is that Geosiris travelled overland along the perimeter of the Indian Ocean. Geosiris jumped continents during periods when the global climate was especially hot and humid. During these times tropical rain forests extended from Africa, around the coast of the Indian Ocean, all the way to Southeast Asia.

As a result, there was a lovely tract of suitable habitat for Geosiris to inhabit and travel through. If this is the case, perhaps there are even more species of the inconspicuous and mysterious Geosiris waiting to be discovered in the rainforests of Southeast Asia.

Elizabeth Joyce, PhD candidate, James Cook University

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.