Most people will be familiar with Australia's unique set of mega- (and not so mega) fauna such as kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, dingoes, wombats, marsupial mice, and of course the egg-laying monotremes, the platypus and the echidna or spiny ant-eater, but how many people are aware of the equally unique and often bizarre array of invertebrates, apart from the dangerous spiders, that is?

In this article in The Conversation, 'Photos from the Field' series, from January 2021 Nick Porch, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Earth Science, Deakin University, Australia, shares some photographs of a small sample of the several hundred thousand uniquely Australian organisms, most of which will be almost completely unknown, even to Australians.

Creationists might like to ignore the bits about 150 million years, Gondwana and allusions to plate tectonics, in the explanation for why Australian bugs tend to be more closely related to South American bugs than those from New Zealand. Evidence of evolution on an old Earth will probably upset them.

The article is reprinted here under a Creative commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistence. The original can be read here:

Photos from the field: zooming in on Australia’s hidden world of exquisite mites, snails and beetles

Dragon springtails (pictured) are widely distributed in forests of eastern Australia — yet they’re still largely unknown to science.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

Which animals are quintessentially Australian? Koalas and kangaroos, emus, tiger snakes and green tree frogs, echidnas and eastern rosellas, perhaps. And let’s not forget common wombats.

Inevitably, most lists will be biased to the more conspicuous mammals and birds, hold fewer reptiles and frogs, and likely lack invertebrates — animals without a backbone or bony skeleton — altogether.

I’m an invertophile, fascinated by our rich terrestrial invertebrate fauna, so my list will be different. I’m enchanted by stunning dragon springtails, by cryptic little Tasmanitachoides beetles, and by the poorly known allothyrid mites, among thousands of others.

Australia’s terrestrial invertebrate multitude contains several hundred thousand uniquely Australian organisms. Most remain poorly known.

To preserve our biodiversity, we first must ask: “which species live where?”. For our invertebrates, we are a long way from knowing even this.

The Black Summer toll

Last year, a team of scientists estimated that the Australian 2019-2020 bushfires killed, injured or displaced three billion animals. That was a lot. But it was also a woefully inadequate estimate, because it only accounted for mammals, reptiles, birds and frogs.

Hidden from view, many trillions more invertebrates burned or were displaced by the fires. And yes, invertebrates are animals too.

A mite from the family Bdellidae (on the right) has captured a springtail, and is using its piercing mouthparts to suck it dry. Mites and springtails are among the most abundant animals on the planet.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

Most invertebrates are poorly known because there are so many species and so few people working on them. In fact, it’s likely only a quarter to one-third of Australia’s terrestrial invertebrate fauna is formally described (have a recognised scientific name).

Meredithina dandenongensis, a species from the wet forests of Victoria. It can be found during the day under rotting logs. The land snail family Charopidae contains hundreds of species across wetter parts of southern and eastern Australia.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

Macrophotography can magnify these wonders for a view into a world most of us are completely unfamiliar with. Even then, it often will be hard to know what we see. Everyone will recognise a kangaroo, but who can identify an allothyrid mite?

The photo below shows an undescribed species of mite from the family Allothyridae, from Mount Donna Buang in Victoria. The mite family Allothyridae has three described Australian species, and dozens more awaiting description.

An undescribed Allothyridae species. Just one of the many species in this group waiting to be studied.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

Mites are a very ancient and diverse group. They can be found abundantly in most terrestrial habitats but are rarely seen because most are several millimetres long or smaller.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

Animal ecologists, most of whom work on vertebrates, often joke that I “study the ‘food’, haha…”. They think they’re funny, but this reflects a deep seated bias — one extending from scientists to the wider public. This limits the development of a comprehensive understanding of biodiversity that has flow-on effects for conservation more broadly.

It’s true: invertebrates are food for larger animals. But their vital role in maintaining Australia’s ecosystems doesn’t end there.

Right way up. pic.twitter.com/7Tn2tdwgcB

— Nick Porch (@InvertoPhiles) November 30, 2020

The moss bug family Peloridiidae, for example, dates back more than 150 million years. For context, the kangaroo family (Macropodidae) is likely 15-25 million years old.

Their history is reflected in the breakup of the ancient supercontinent, Gondwana. In fact, Australian species of moss bugs are more closely related to South American species than to those from nearby New Zealand.

Chasoke belongs to the beetle family Staphylinidae, which is currently considered the largest family of organisms on Earth, with more than 60,000 scientifically described species. Mt. Donna Buang, Victoria.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

Similar stories can be told from across the invertebrate spectrum. The photo below shows a few examples of these relics from Gondwana.

Peloridiid bugs — such as Hemiodoecus leai China, 1924 (top left) — are restricted to the wettest forests where they feed on moss. Top right: A new species of Acropsopilio (Acropsopilionidae) harvestman from the Dandenong Ranges. Bottom left: a new velvet worm from the Otway Ranges. Bottom right: Tasmanitachoides hobarti from Lake St Clair in central Tasmania.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

Overprinting this deep history are the changes that occurred in Australia, especially the drying of the continent since the middle Miocene, about 12-16 million years ago.

This continent-wide drying fragmented wet forests that covered much of the continent, resulting in the restriction of many invertebrate groups to pockets of wetter habitat, especially along the Great Dividing Range and in southwestern Australia.

A consequence of this was the evolution in isolation of many “short-range endemic” species.

A short-range endemic species means their geographic distribution is less than 10,000 square kilometres. A short-range endemic mammal you might be familiar with is Leadbeater’s possum, restricted to the wet forests of the Victorian Central Highlands.

This is Idolothrips spectrum, the largest thrips in the world. It’s called the giant thrips, even though it’s less than 10mm long. Dandenong Ranges, Victoria.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

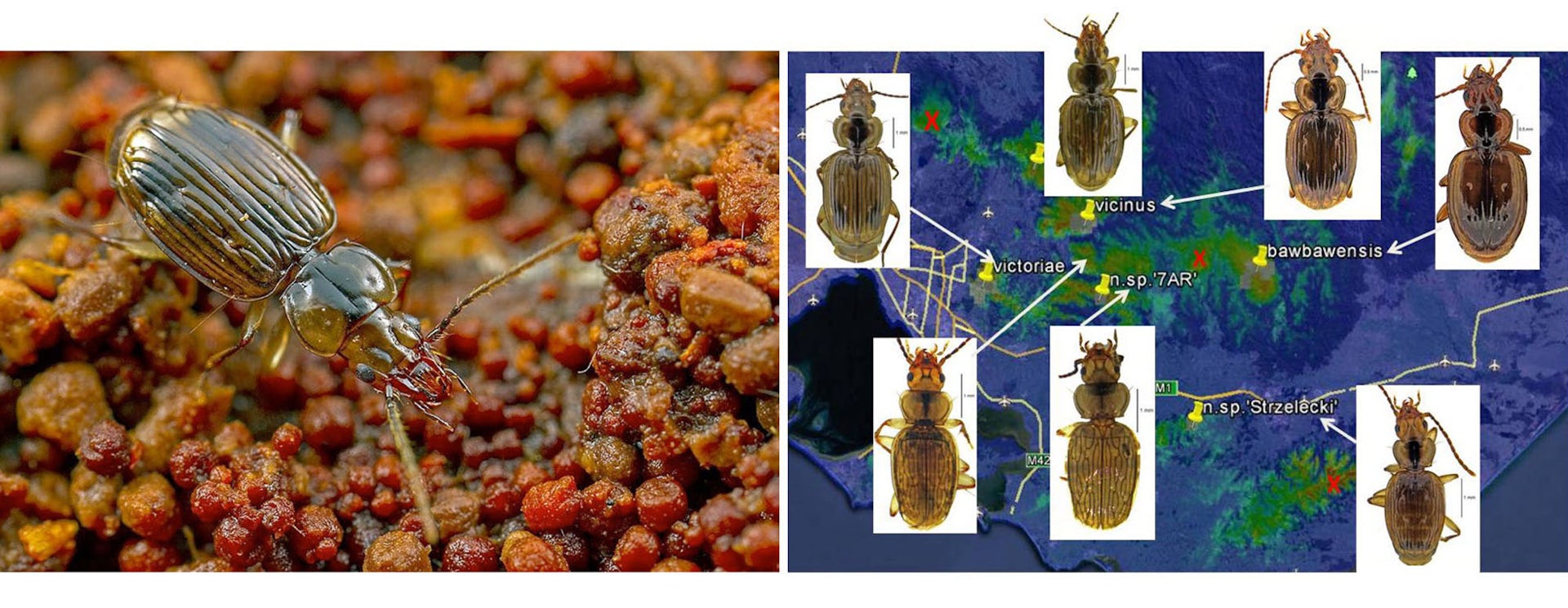

Take Tropidotrechus, pictured below, a genus of beetles mostly restricted to the same region as Leadbeater’s possum. They, however, divide the landscape at a much finer scale because they’re restricted to deep leaf litter in cool, wet, forest gullies.

As Australia dried, populations of Tropidotrechus became isolated in small patches of upland habitat, evolving into at least seven species across the ranges to the east of Melbourne.

Tropidotrechus victoriae, Victoria’s unofficial beetle emblem (left). Related described and undescribed species are found in the nearby Central Highlands and South Gippsland ranges (right)

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

The trouble with knowing so little about Australia’s extraordinary number of tiny, often locally unique invertebrates, is that we then massively underestimate how many of them are under threat, or have been badly hit by events like the 2019-2020 fires.

If we wish to conserve biodiversity widely, rather than only the larger charismatic wildlife, then enhancing our knowledge of our short-range species should be a high priority.

You don’t necessarily need specialist equipment to take pictures of our fascinating invertebrates. This is a phone picture of mating Repsimus scarab beetles (relatives to the Christmas beetles). It was taken at Bemboka in NSW, which burnt during the 2019-2020 fires.

Credit: Nick Porch, Author provided

You can join iNaturalist, a citizen science initiative that lets you upload images and identify your discoveries. Perhaps you’ll discover something new — and a scientist just might name it after you.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.