A picture taken on September 6, 2021, shows the reconstruction of the face of the oldest Neanderthal found in the Netherlands, nicknamed Krijn, on display at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden.

Bart Maat/ANP/AFP Via Getty Images

Creationists need to resort to unproven claims of common design, to explain the same or closely similar structures and processes being found in related species. In contrast to the scientific explanation of observable evidence of natural processes with no plan, no intent and no magical mysteries, Creationists need to invoke an unproven, unexplained and unfalsifiable magic supernatural entity, claiming this to be the better of the two for no other reason than that their mummy and daddy believed it and it makes them feel special.

Just such an example of the evidence of common origins has recently been published in Nature Ecology & Evolution which shows that both modern Homo sapiens and Neanderthals had the same rapid evolution of the organisation of the brain that is believed to be responsible for high levels of cognitive ability.

The fact that this is present in two closely related species is highly suggestive that it was present at least in their last common ancestor. It also suggests that Neanderthals had a level of cognitive ability on a par with modern humans.

The research and its significance is the subject of an article in The Conversation by three of the researchers, Professor Stephen Wroe, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia; Dr. Gabriele Sansalone, Institute of Marine Sciences, National Research Council, Messina, Italy, and Professor Pasquale Raia, Department of Earth Sciences, Environment and Resources, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Monte Sant’Angelo, Naples, Italy. That article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original article can be read here.

Human and Neanderthal brains have a surprising ‘youthful’ quality in common, new research finds

Neanderthal skull.

Credit: Petr Student/Shutterstock

Stephen Wroe, University of New England; Gabriele Sansalone, Institute of Marine Sciences, and Pasquale Raia, University of Naples Federico II

Many believe our particularly large brain is what makes us human – but is there more to it? The brain’s shape, as well as the shapes of its component parts (lobes) may also be important.

Results of a study we published today in Nature Ecology & Evolution show that the way the different parts of the human brain evolved separates us from our primate relatives. In a sense, our brains never grow up. We share this “Peter Pan syndrome” with only one other primate – the Neanderthals.

Our findings provide insight into what makes us human, but also further narrow any distinction between ourselves and our extinct, heavy-browed cousins.

Tracking the evolution of the brain

Mammalian brains have four distinct regions or lobes, each with particular functions. The frontal lobe is associated with reasoning and abstract thought, the temporal lobe with preserving memory, the occipital lobe with vision, and the parietal lobe helps to integrate sensory inputs.

The four main parts of the brain form the cerebral cortex.

Credit: The Conversation, CC BY-ND

In particular, we wanted to know how human brains might differ from other primates in this respect.

One way to address this question is to look at how the different lobes have changed over time among different species, measuring how much shape change in each lobe correlates with shape change in others.

Alternatively, we can measure the degree to which the brain’s lobes are integrated with each other as an animal grows through different stages of its life cycle.

Does a shape change in one part of the growing brain correlate with change in other parts? This can be informative because evolutionary steps can often be retraced through an animal’s development. A common example is the brief appearance of gill slits in early human embryos, reflecting the fact we can trace our evolution back to fish.

We used both methods. Our first analysis included 3D brain models of hundreds of living and fossil primates (monkeys and apes, as well as humans and our close fossil relatives). This allowed us to map brain evolution over time.

Our other digital brain data set consisted of living ape species and humans at different growth stages, allowing us to chart integration of the brain’s parts in different species as they mature. Our brain models were based on CT scans of skulls. By digitally filling the brain cavities, you can get a good approximation of the brain’s shape.

A surprising result

The results of our analyses surprised us. Tracking change over deep time across dozens of primate species, we found humans had particularly high levels of brain integration, especially between the parietal and frontal lobes.

But we also found we’re not unique. Integration between these lobes was similarly high in Neanderthals too.

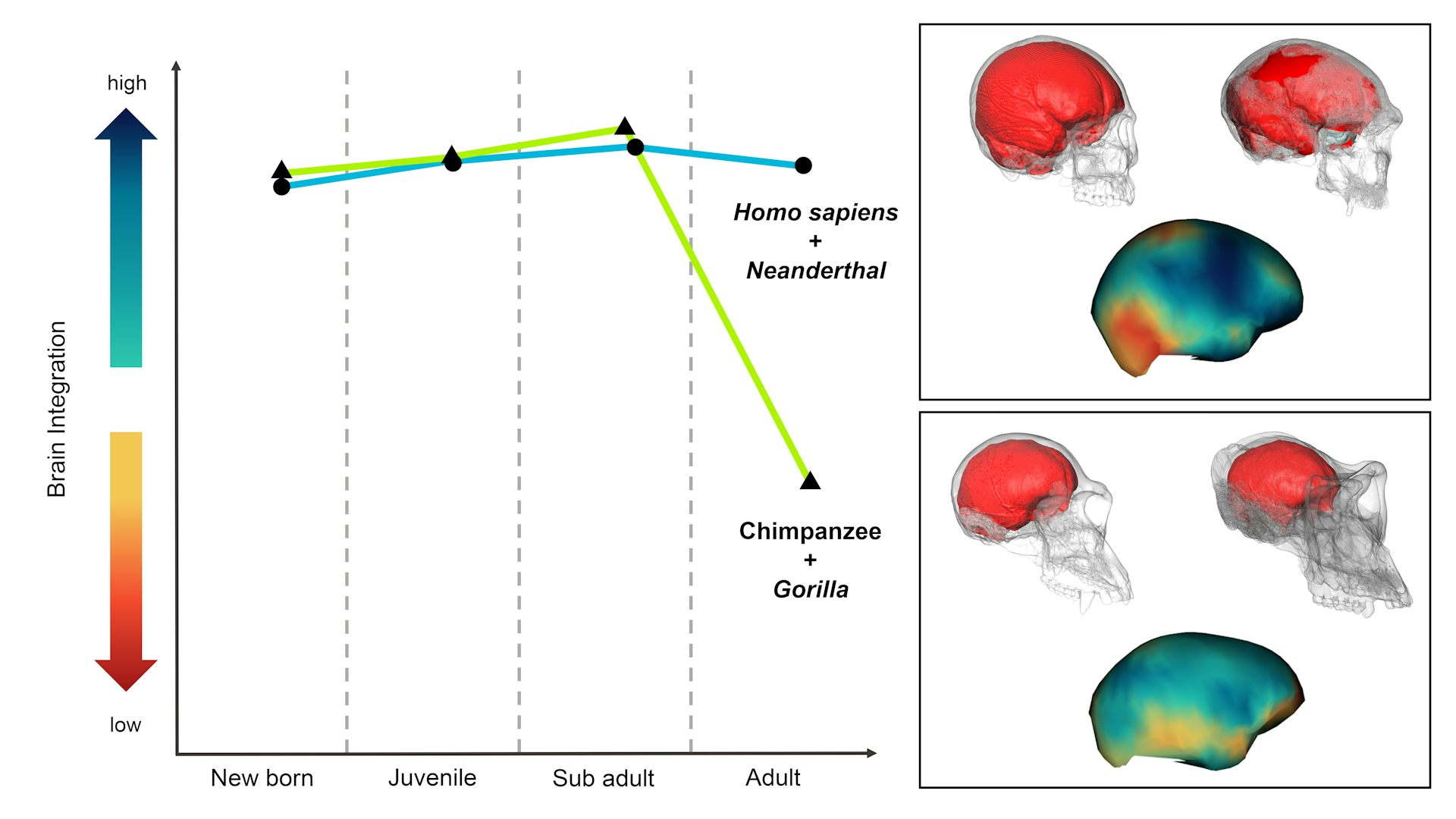

Looking at changes in shape through growth revealed that in apes, such as the chimpanzee, integration between the brain’s lobes is comparable to that of humans until they reach adolescence.

At this point, integration rapidly falls away in the apes, but continues well into adulthood in humans.

Left: a chart shows the degree of integration between the brain’s lobes, with cooler colours indicating higher integration. Right: translucent skulls of a human, Neanderthal, chimp and gorilla, showing the digitally reconstructed brains within.

Credit: Gabriele Sansalone and Marina Melchionna, Author provided

So what does this all mean? Our result suggest what distinguishes us from other primates is not just that our brains are bigger. The evolution of the different parts of our brain is more deeply integrated, and, unlike any other living primate, we retain this right through into adult life.

A greater capacity for learning is typically associated with juvenile life stages. We suggest this Peter Pan syndrome played a powerful role in the evolution of human intelligence.

There’s another important implication. It’s increasingly clear that Neanderthals, long characterised as brutish dullards, were adaptable, capable and sophisticated people.

Archaeological findings continue to mount support for their development of sophisticated technologies, from the earliest known evidence of string, to the manufacture of tar. Neanderthal cave art shows they indulged in complex symbolic thought.

Us and them

Our results further blur any dividing line between us and them. This said, many remain convinced some innately superior intellectual quality gave us humans a competitive advantage, allowing us to drive our “inferior” cousins to extinction.

There are many reasons why one group of people may dominate, or even eradicate others. Early Western scientists sought to identify cranial features linked to their own “greater intelligence” to explain world domination by Europeans. Of course, we now know skull shape had nothing to do with it.

We humans may ourselves have come perilously close to extinction 70,000 years ago.

If so, it’s not because we weren’t smart. If we had gone extinct, perhaps the descendants of Neanderthals would today be scratching their heads, trying to figure out just how their “superior” brains gave them the edge.

Stephen Wroe, Professor, University of New England; Gabriele Sansalone, PostDoc fellow, Institute of Marine Sciences, and Pasquale Raia, Professor of Paleontology and Paleoecology, University of Naples Federico II

AbstractCreationists, of course, are used to the facts not supporting their beliefs and have developed all manner of coping mechanisms, so little bit of evidence such as this are unlikely to win many over to the intellectual rigours of science as a route to the truth of the world we live in. Theirs is a puny little god who can be seriously damaged by a whiff of doubt and so appreciates the self-sacrifice of intellectual dishonesty, just so long as its followers never consider changing their minds or contemplating the possibility of being wrong, for that would put the income stream of the cult leaders at risk.

There is controversy around the mechanisms that guided the change in brain shape during the evolution of modern humans. It has long been held that different cortical areas evolved independently from each other to develop their unique functional specializations. However, some recent studies suggest that high integration between different cortical areas could facilitate the emergence of equally extreme, highly specialized brain functions. Here, we analyse the evolution of brain shape in primates using three-dimensional geometric morphometrics of endocasts. We aim to determine, firstly, whether modern humans present unique developmental patterns of covariation between brain cortical areas; and secondly, whether hominins experienced unusually high rates of evolution in brain covariation as compared to other primates. On the basis of analyses including modern humans and other extant great apes at different developmental stages, we first demonstrate that, unlike our closest living relatives, Homo sapiens retain high levels of covariation between cortical areas into adulthood. Among the other great apes, high levels of covariation are only found in immature individuals. Secondly, at the macro-evolutionary level, our analysis of 400 endocasts, representing 148 extant primate species and 6 fossil hominins, shows that strong covariation between different areas of the brain in H. sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis evolved under distinctly higher evolutionary rates than in any other primate, suggesting that natural selection favoured a greatly integrated brain in both species. These results hold when extinct species are excluded and allometric effects are accounted for. Our findings demonstrate that high covariation in the brain may have played a critical role in the evolution of unique cognitive capacities and complex behaviours in both modern humans and Neanderthals.

Sansalone, Gabriele; Profico, Antonio; Wroe, Stephen; Allen, Kari; Ledogar, Justin; Ledogar, Sarah; Mitchell, Dave Rex; Mondanaro, Alessandro; Melchionna, Marina; Castiglione, Silvia; Serio, Carmela; Raia, Pasquale (2023)

Homo sapiens and Neanderthals share high cerebral cortex integration into adulthood

Nature Ecology & Evolution; 7(1), 42-50; DOI: 10.1038/s41559-022-01933-6

© 2023 Springer Nature Ltd.

Reprinted under the terms of s60 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.