Creationism in Crisis

Humans Carry Traces of Ancestral Species

Humans Carry Traces of Ancestral Species

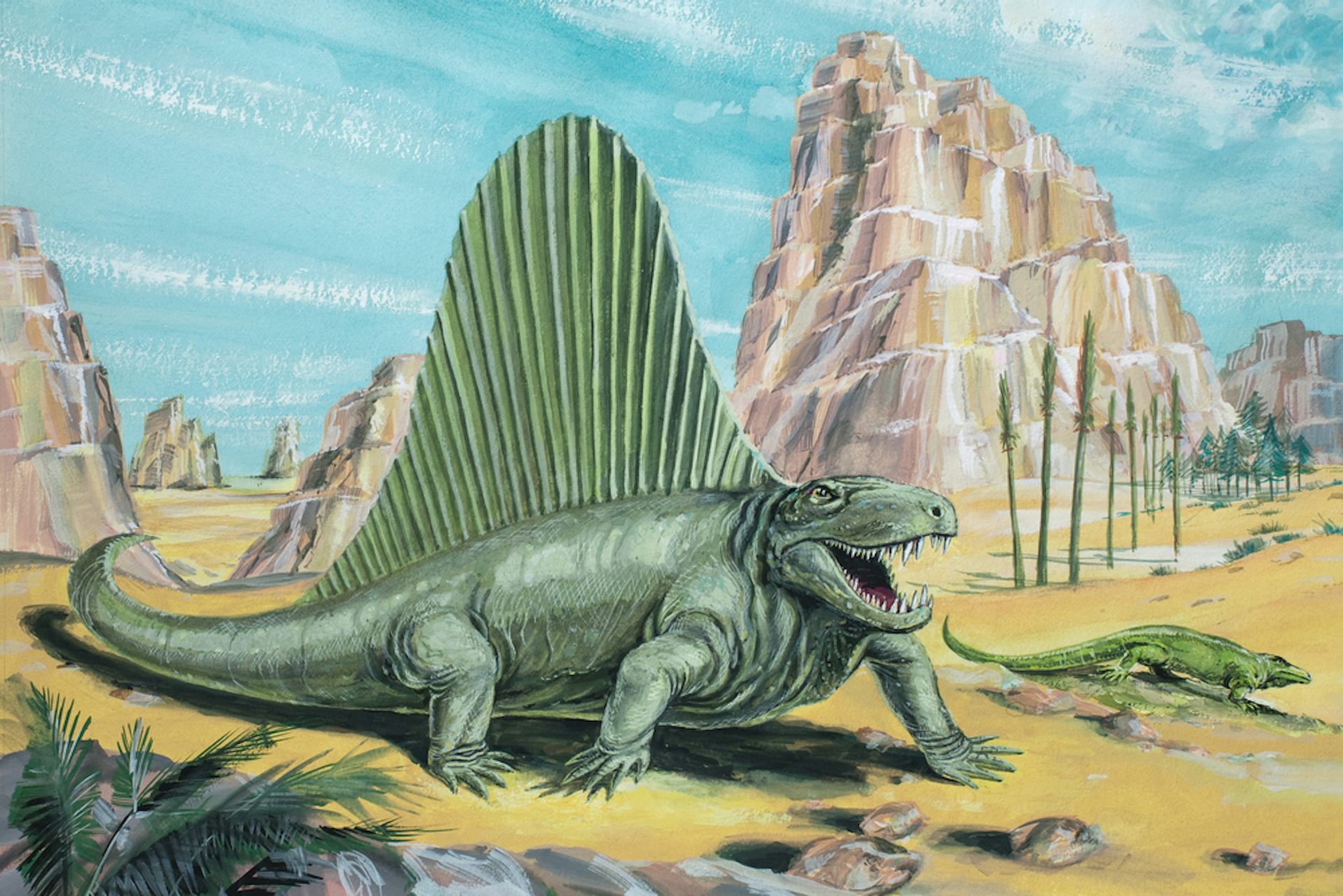

A reconstruction of the permian synapsid

Dimetrodon grandis

Dimetrodon grandis

We can still see these 5 traces of ancestor species in all human bodies today

Your genes haven't always been human. In fact most of them have spent far more time not being human than they have being human.

This is because you inherited them from your parents and their parents before them, going right back to before your ancestors were human; before they were mammals, before they were vertebrates, and even before they were multicellular organisms.

To quote from my book, What Makes You So Special? From the Big Bang To You:

You are the product of billions of passes through the sieve of selection and at every pass your gene-line passed the fitness test. Your genes are good at surviving; and you are unique in the history of the cosmos. The likelihood of you being alive at all is almost vanishingly small and yet here you are. Never before has anyone with your combination of genes, your collection of atoms and your history existed.In the following article, reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence, Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Australia, identifies five key features we have inherited from remote ancestors. These are:

And you never will again.

Almost all your genes have spent much longer being something else than they have being human. Your ancestors were there when Europe and Africa split off from the Americas. They were there as small mammal-like reptiles when dinosaurs ruled the earth. They saw pterodactyls flying overhead. They survived the mass-extinction which ended the dinosaurs’ reign and they saw the birds and the bats grow wings and take to the air.

Your ancestors swam in the Cambrian seas and crawled out onto the land as early air-gulping fish destined to become four–legged animals with lungs. Your ancestors lived through the Carboniferous era when dense forests of tree ferns grew in steaming jungles where dragonflies with meter-wide wings flew. They saw the trees fall and form the piles of vegetation destined to be coal as the climate changed and the Carboniferous forests collapsed. They saw the first flowering plants as plants and insects formed their mutual-benefit society.

Your ancestors lived through the first great toxic waste disaster when the cyanobacteria produced oxygen and triggered a mass extinction; and they learned to turn it to their advantage by evolving aerobic respiration.

Your ancestors were bacteria; maybe they were archaea; they may have been the strange Ediacarans which were the earliest known multi-cellular organisms. In almost every one of your cells, in your genes, you carry a record of your evolution, of the entire human evolution story, and of a great deal of the evolution story of every other living thing.

Your journey through space and time has been an adventure of disasters, adaptation, survival and recovery, many, many times you will have been on the brink of extinction - the fate of 99% of all known ancient species - yet your ancestors survived and because they were good at surviving you are here and now.

The original article has been reformatted for stylistic consistency.

- Bipedal walking, including changes to our pelvis - inherited from archaic hominins.

- Openings in our skull, inherited from our synapsid ancestors, which includes relatives of the Dimetrodon.

- Five fingers and toes, inherited from our fish ancestors that first emerged onto land.

- Teeth, inherited from early jawed fish from the Silurian, about 14 million years ago.

- The spinal chord and vetebrae, inherited from early chordates which evolved a 'notocord', some 500 million years ago.

We can still see these 5 traces of ancestor species in all human bodies today

Credit: Elia Pellegrini/Unsplash

Many of us are returning to work or school after spending time with relatives over the summer period. Sometimes we can be left wondering how on earth we are related to some of these people with whom we seemingly have nothing in common (especially with a particularly annoying relative).

However, in evolutionary terms, we all share ancestors if we go far enough back in time. This means many features in our bodies stretch back thousands or even millions of years in our great family tree of life.

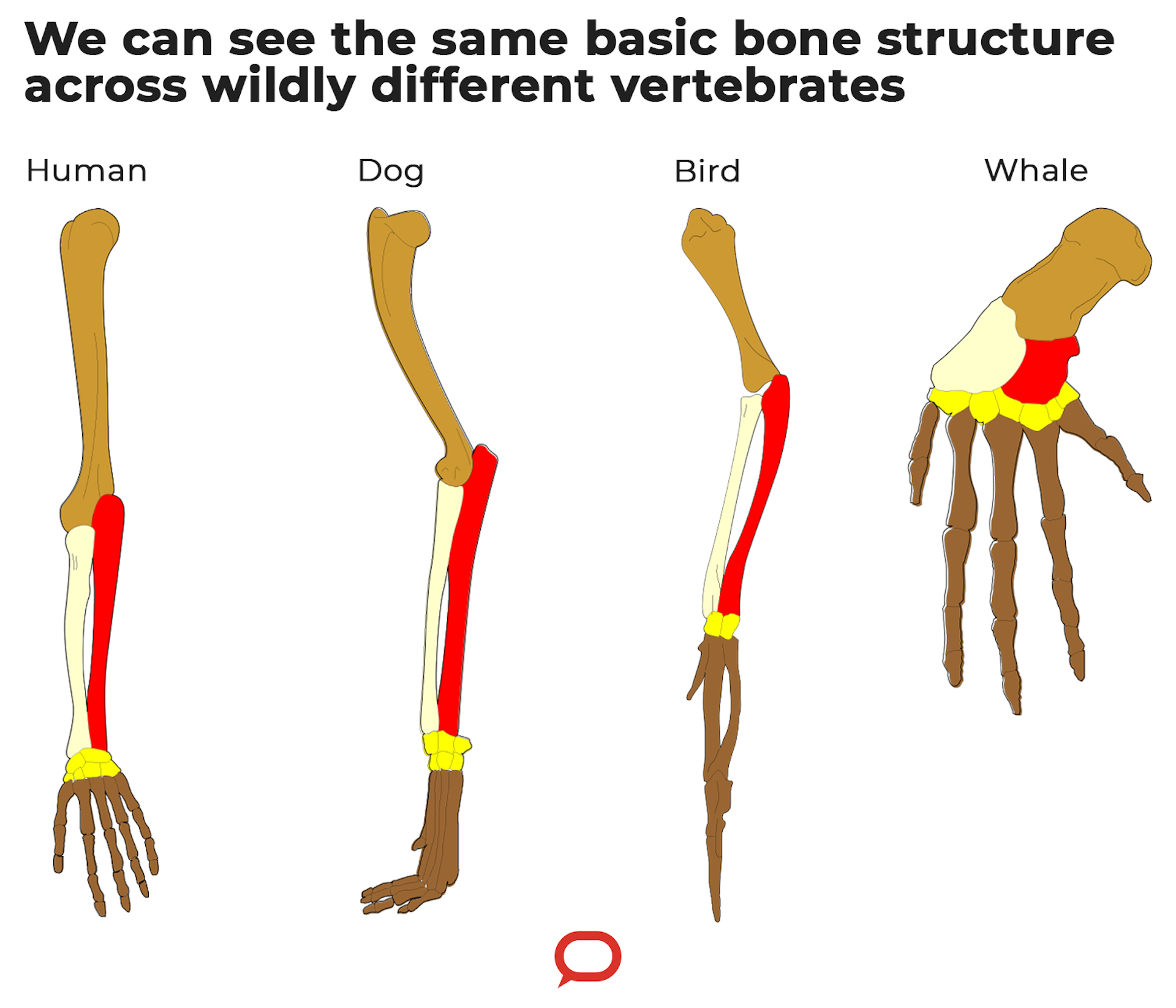

In biology, the term “homology” relates to the similarity of a structure based on descent from a shared common ancestor. Think of the similarities of a human hand, a bat wing and a whale flipper. These all have specialist functions, but the underlying body plan of the bones remains the same.

Credit: Волков Владислав Петрович/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Here are five examples of ancient traits you might be surprised to learn are still seen in humans today.

One step ahead

What makes us human? This question has plagued scientists and scholars for centuries. Today it seems relatively straightforward to tell who is a human and who is not, but looking through the fossil record, things very quickly become less clear.

Does humanity begin with the origins of our own species, Homo sapiens, from 300,000 years ago? Or should we stretch things back more than three million years to ancestors such as “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis) from eastern Africa? Or even further back to our split from the other great apes?

Whatever line you draw in the sand to pinpoint the birth of humanity, one thing is certain. The act of habitually walking around on two legs, known as “bipedalism”, was one of our ancestors’ greatest steps.

It’s hard to overestimate the importance of bipedalism in human evolution.

Credit: Microgen/Shutterstock

Importantly, we know from fossil skulls that rapid increases in our brain size occurred shortly after we started walking upright. This required changes to the pelvis to allow for our larger-brained babies to fit through a widened birth canal.

Our broadened pelvis (sometimes called iliac flaring) is a homologous feature shared with several lineages of early fossil humans, as well as all those living today.

Those big brains of ours then fuelled an explosion of art, culture and language, important concepts when considering what makes us human.

A hole in your head

In addition to your eyeballs sitting in their orbits, you may be surprised to learn that you have other large holes (known as fenestrae) in your skull.

A single window is found on each side of the human skull, uniting us with our shared common ancestors from over 300 million years ago.

Animals with this single window in their skulls are known as synapsids. The word means “fused arch”, referring to the bony arch found underneath the opening in the skull behind each eye.

Today all mammals, including humans, are synapsids (but reptiles and birds are not).

Other famous synapsids from prehistoric times include the often misidentified Dimetrodon. The sail-backed ancient reptile is commonly mistaken for a dinosaur. However, with its sprawling limbs and single temporal fenestra it instead belongs to a lineage sometimes referred to as “mammal-like reptiles”, although we prefer the more accurate term of synapsid.

Artist’s impression of a Dimetrodon, a long-extinct animal that was not a dinosaur.

Credit: David Roland/Shutterstock

I am typing this article on my computer using ten of my digits (fingers and thumbs; digits also refer to toes but mine don’t reach the keyboard).

This pattern of five digits in the human hand or foot, known as a “pentadactyl limb”, is found in most amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.

But fish don’t have fingers and toes, so when was it that digits first evolved?

A recent study by myself and colleagues actually described the first digits found preserved within a fish fin. We used powerful imaging methods to peer inside a 380-million-year-old fossil called Elpistostege from Quebec, Canada, to reveal the oldest fish fingers!

Somewhat surprisingly, the first fish to evolve digits still retained fin rays around them so these bones would not have been visible on the animal externally.

The earliest tetrapods (four-limbed animals with a backbone that eventually moved out of water and onto land) “experimented” with the number of digits, sometimes being found with six, seven or eight of them.

These earliest tetrapods were likely still living in the water. It wasn’t until tetrapods became truly terrestrial that the five-digit limb arrived. This arrangement most likely arose as a practical solution to weight bearing on land.

Long in the tooth

Does your mind wander when you brush your teeth? Well, have you ever considered how evolutionarily old your pearly whites are?

A fossil of a Helicoprion bessonowi tooth whorl from the Ural Mountains, Russia.

Credit: Citron/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

That new fish, a very early jawed vertebrate, was named Qianodus duplicis and is only known from isolated specialised teeth known as “whorls”. A tooth whorl is a bizarre row of teeth that curls in on itself in a spiral pattern (most famously present in the buzz-saw shark, Helicoprion).

Nevertheless, the teeth in the Chinese jawed fish have a number of features found in other modern jawed vertebrates, which highlight their relevance in understanding the evolution of our very own gnashers. Chomp on that!

Grow a spine

To “grow a spine” means to become emboldened and confident. The first animals to do just that must have surely been courageous to venture out into the perilous ancient seas 500 million years ago.

First, these worm-like animals evolved a “notochord” – a rod built of cartilage running along the back of the body. This enabled the attachment of segmented muscle blocks and a long tail extending beyond the anus. All animals with a notochord are called chordates, and includes everything from sea squirts to sea gulls, comprising more than 65,000 living species.

To get an idea of the first chordates, today we can look to animals such as the lancelet (known as Amphioxus or Branchiostoma). Lancelets look a bit like tiny, primitive fishes without fins. They swim by undulating their body from side to side.

Next come those with well organised heads (craniates), and those in which the notochord is replaced by a backbone in adults (vertebrates).

A backbone is built of individual segmented bones (vertebrae) which fit together in a specific interlocking pattern. We have a few tantalising fossils representing the earliest known examples of vertebrates, such as Metaspriggina known from Canada, or Haikouichthys from China in rocks more than 500 million years old.

So, whether it be your large brain and broad pelvis from walking around upright, skull with a single opening and bony arch, your fingers, toes, teeth or spinal cord, we humans share many ancient features in our bodies.

And so, in the words of the poet and activist Maya Angelou, it may be worth remembering that we are more alike than we are unalike.

Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.