Icons of Feminism

Mary Wollstonecraft and Rejection of Religious Doctrine.

Mary Wollstonecraft and Rejection of Religious Doctrine.

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie, c. 1797

Source: Wikipedia

Mary Wollstonecraft: an introduction to the mother of first-wave feminism

Reading this account of the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, one of the first 'radical' feminists, by Bridget Cotter, Lecturer in Social Sciences, University of Westminster, UK, one of the things that stands out most vividly is the religious inspiration for the repression and subjugation of women in Victorian England, and how much of that religion is now seen as wrong and antisocial by the vast majority of decent people.

Far from providing society with a fixed moral framework, religion has served to hold back moral development as society evolves, only to have to reluctantly acceded to the new standards when the tension becomes irresistible.

One of the great crimes of religion, or rather the clerics who control it, is the theft of control of social ethics by a clique who knew they would lose control if they allowed the people too much freedom to think for themselves.

If we give all men the vote, where will it all end? Women demanding the same?!"

"If we give way on feminism, where will it all end? Women priests?!"

"If we give way on contraception, where will it all end? Sexually liberated women?!"

“If we give way on same-sex marriage, or allow gays to become priests, Where will it all end?

… Etc, etc, etc.

Because she challenged these imposed social norms and questioned the authority of those who sought to impose them on us, Mary Wollstonecraft was considered a dangerous revolutionary. Ironically she was opposed most vigorously by the same church that proudly, but wrongly, proclaims its founder as a dangerous revolutionary who challenged authority and the prevailing social norms and cultural ethics.

And today, much of what Mary Wollstonecraft campaigned for is taken for granted as right and proper in most civilised countries.

Bridget Cotter's article in The Conversation is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license. The original can be read here.

Mary Wollstonecraft: an introduction to the mother of first-wave feminism

A portrait of Wollstonecraft painted by John Opie in 1790-91.

Source: Wikipedia.

Bridget Cotter, University of Westminster

Mary Wollstonecraft has had something of a revival in recent years.

Though considered the mother of first-wave feminism, the 18th-century philosopher long endured her share of trolls refusing to take her seriously. She was dubbed a “hyena in a petticoat” by contemporary politician and writer Horace Walpole, accused of being “unsexed”, unladylike, and of having no shame. She even fell out of favour with some 20th-century feminists.

But in the last decade and a half, popular interest in her life and work has grown exponentially with the emergence of Wollstonecraft blogs,societies,campaigns and even Instagram and Facebook accounts in her name. Her public commemoration has ranged from the traditional blue plaque to a controversial sculpture in her old north London neighbourhood.

As the author of an impassioned plea for human rights, and one of the earliest and most-read statements of feminism, Wollstonecraft today has a well-deserved status as a feminist icon. But we should also take pause when looking at how she is presented, especially when she is shown as the main representative of British feminism.

Education as politics

Born in 1759 in London to a middle-class family, Wollstonecraft spent her youth watching her mother suffer at the hands of an abusive father. An avid reader, frustrated by the limited education and career options open to girls, Wollstonecraft set out to educate herself.

With her sister and friend, she opened a day school for girls in Newington Green. The focus of most of her writings was moral conduct, education and child rearing because she believed that this was the main route to changing the culture and creating a new path for women and girls. For Wollstonecraft, education was political.

Like her fellow north London radicals, Wollstonecraft was a passionate supporter of the French Revolution. She hoped for a similar shift toward democratic republicanism in British politics.

When the political philosopher and MP, Edmund Burke, wrote his famous treatise condemning the revolution and defending the British monarchy, she was so incensed that she wrote and published a response. This was the start of the so-called “pamphlet wars” which resulted in hundreds of responses to Burke (the most famous of which was Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man).

Both Paine and Wollstonecraft defended a doctrine of “natural rights”. This is the idea that man is naturally endowed with rational thought and an ability to think independently, and therefore judge for himself.

But neither Paine nor most of the French revolutionaries that Wollstonecraft so admired actively extended this thinking to women. The new French Republic, in fact, relegated all women (and men without property) to the status of “passive” (non-voting) citizens who were not considered independent enough to make their own decisions.

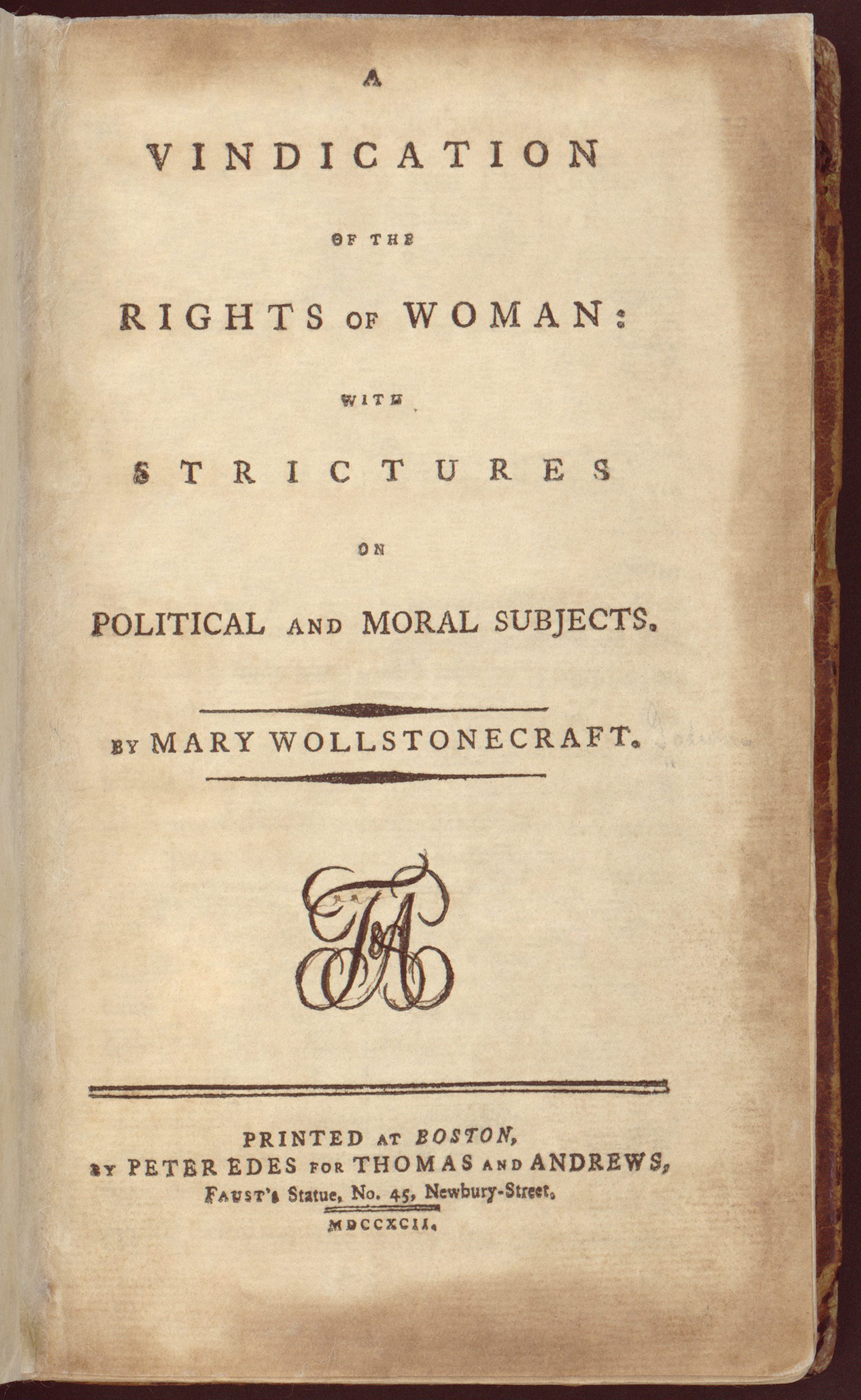

Wollstonecraft’s most famous text, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, is largely a treatise on the edifying effects of the right kind of education on virtue.

Wollstonecraft did not mean sexual purity when she spoke of virtue, however. Virtue was indicative of moral character and primarily expressed in the ability to make sound, informed and rational judgements.

Moral character also included, for Wollstonecraft, humility and self-discipline and a willingness to look outward from selfish or trivial wants to the needs of others. These were the republican (and indeed Protestant) virtues that good citizens in the new post-revolutionary democracies would need.

Wollstonecraft argued that women are equally capable of acquiring these virtues and of benefiting from a full education if only given the chance to develop their capacities in the same way as men.

Gender norms as social constructs

The idea that reason is not the sole provenance of men also meant that Wollstonecraft was already making an argument, often attributed to Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex and to the so-called second-wave feminism of the 1950s and 1960s, that gender norms are socially constructed.

Rational qualities, argues Wollstonecraft, are not naturally gendered. They are learned and shaped by environment, especially by upbringing, education and culture. If education is narrow and confined, it will produce narrow and confined thinking. This is what she meant when she wrote of women: “Make them free and they will quickly become wise and virtuous.”

The title page from the first American edition of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

Wollstonecraft wanted to free women from being forced to focus solely on trivial accomplishments that would make them a better wife. Wollstonecraft herself lived a life that largely defied convention, but it was evidently not an easy one.

This is, far too often, still the life that women live today: caught in a struggle to break free of preconceived notions about who and what we can be, what we should wear, how we should look, and what we should value in ourselves.

Wollstonecraft asserted the simple idea that women were fully fledged people with the capacity to decide on and forge a path for themselves. Obvious to us, but the revolutionary character of this idea, should not be underestimated.

It is the same notion that nearly a century later got John Stuart Mill lampooned and laughed at in the House of Commons when, as Westminster MP, he proposed to substitute the word “persons” for the word “men” in the voting reform bill of 1867 so as to include women in universal suffrage.

This idea, that women are rational beings with a right to self-determination, must still be fought for daily around the world. This is the case in every instance where, as women, we are forced to assert that we are not objects, or property, that we have not been made for someone else’s use or pleasure, that it is not justified to exclude us from education or politics, or prevent us from speaking our minds, whether through laws, violence, intimidation or ridicule.

Personal liberation

Wollstonecraft has striking relevance for us and she is responsible for inspiring generations of activists. However, she had her blind spots. She was not writing for working class women and she said little about women of colour in spite of her abolitionism. Today’s women around the world deal with issues that Wollstonecraft could never have imagined.

Nor is it helpful when she is simplistically presented as paving the way for the suffragettes. In claiming Wollstonecraft, the suffragette movements rescued her memory from a largely negative obsession with her sexual morality. But they also did her a disservice by reducing her aims to a battle for legal and political equality.

Equal treatment is indeed a necessary condition for women’s progress. But it is not a sufficient condition for women’s freedom. Wollstonecraft herself was more interested in personal liberation. In fact, she never made voting a focus of her writings.

Wollstonecraft wanted something much more than voting, something that too often we still do not have: liberation from prescribed notions of who or what we can be and from the fear of being who we are.

Liberation from oppression means being able to define ourselves and the direction of our lives. And this requires access to the intellectual resources and knowledge needed to develop independence of mind. This is Wollstonecraft’s most important message, and one that should speak to everyone regardless of gender.

Bridget Cotter, Lecturer, Social Sciences, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.Later we see this casual misogyny being used to justify the rape of women war booty, with:

Genesis 3:16

When thou goest forth to war against thine enemies, and the LORD thy God hath delivered them into thine hands, and thou hast taken them captive, And seest among the captives a beautiful woman, and hast a desire unto her, that thou wouldest have her to thy wife;Read that again and relate it to the stories of Russian soldiers raping Ukrainian women today. Why, if God's moral laws are fixed and eternal, do we find repugnant today that which was taken for granted in the Bronze Age? Why is what was expected of soldiers in the Old Testament, considered a morally repugnant war crime today?

Then thou shalt bring her home to thine house, and she shall shave her head, and pare her nails; And she shall put the raiment of her captivity from off her, and shall remain in thine house, and bewail her father and her mother a full month: and after that thou shalt go in unto her, and be her husband, and she shall be thy wife.

Deuteronomy 21: 10-13

But nothing much had changed by the Early Iron Age when we find these little gems as early Christian cult leaders instructed their followers in misogyny, using the Adam & Eve myth as an excuse:

Let the woman learn in silence with all subjection. But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence. For Adam was first formed, then Eve. And Adam was not deceived, but the woman being deceived was in the transgression.And still, in 21 Century America, we have a fundamentalist Christian pastor, who writes anonymously (understandably) under the pseudonym, Larry Solomon, telling his followers:

1 Timothy 2: 11-14

For after this manner in the old time the holy women also, who trusted in God, adorned themselves, being in subjection unto their own husbands: Even as Sara obeyed Abraham, calling him lord: whose daughters ye are, as long as ye do well, and are not afraid with any amazement.

1 Peter 3: 5-6

Biblically speaking the modern concept of “marital rape” is an oxymoron. It is impossible from a Biblical perspective for a man to rape his wife. The Bible defines unlawful forced sex or what we would call rape as when a man forces a woman who is not married to him to have sex with him see Deuteronomy 22:23-29 for more on this. God condones forced sex in marriage in Deuteronomy 21:10-14 and he symbolizes himself as a husband who “humbles” his wife Israel in Deuteronomy 8:2-3. For more on this subject see my article “Why the Bible Allows Forced Sex in Marriage“.Imagine how difficult it must have been for enlightened humanists like Mary Wollstonecraft campaigning against this grotesque dehumanisation of half the human population at a time when these attitudes still held sway in society, supported by the 'divine authority' of a holy book written before people knew any better.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.