Old Dead Gods

No-One Mourns for the Old Dead Gods of Arabia

No-One Mourns for the Old Dead Gods of Arabia

Mustatil ('rectangles") in the heart of Al-Nafūd Desert, Northern Saudi Arabia, are the remains of religious buildings from 7,000 years ago

Enigmatic ruins across Arabia hosted ancient ritual sacrifices

Long before a clan of camel herders and traders along the western edge of Arabia were forced by tribal loyalty to follow a new, charismatic 'Prophet of Allah", and long before a tribe of Canaanite hill farmers in the hill of southern Syria adopted the god Yahweh from the local pantheon as their own, and created a mythical history to give them a unique identity and justify their land-theft, genocide and territorial expansion, scattered bands of early pastoralists had banded together to build hundreds of massive monuments for religious rituals in the Al-Nafūd Desert in the north of Arabia, close to the Western end of the 'fertile crescent'.

1 of 11

Detail of north-west (preserved) interlocking cells of associated feature IDIHA-F-0011149.

2 of 11

The four I-type platforms located west of IDIHA-F-0011081, photo orientated west.

3 of 11

The main (central) chamber of mustatil IDIHA-F-0011081 with three up-right stones (A-C). Flat stones in centre of image acted as support for primary up-right stone in the rear. The blocked doorway is visible in the left of the photo.

4 of 11

Transverse grooved hammer stone found upside down and in situ in Phase 1.

5 of 11

Bos sp. horn (#0032) recovered from Phase 4A, note the positioning in relation to up-right stone A.

6 of 11

Horns found on a collapsed “bench” in Phase 4B. Left to right, large cattle horns/sheaths (#0043) and (#0033), goat horn sheath (#0047), goat (#0041), and cattle horn (#0040).

8 of 11

Riverstone surface associated with courtyard, further pebbles were set within the doorway.

9 of 11

Two mustatil at site IDIHA-0030862 in Khaybar County orientated (base) towards a body of standing water, photo orientated west.

10 of 11

Three mustatil at site IDIHA-0030914, orientated (base) towards a small seasonal wadi in Khaybar County, photo orientated south-west.

11 of 11

Mustatil IDIHA-F-0011081 orientated (head) towards a playa located to the east, photo orientated east.

They are also associated with elaborate rock-carvings of strange geometric shapes and patters, which were probably originally painted.

As with the Pyramids and the Bronze Age structures of Stonehenge and Silbury Hill, in Wiltshire, UK, they suggest an organised state with an economy strong enough to provide a surplus wealth and food production sufficient to finance these constructions and feed the workers.

And yet, because they left no records, like the religion that inspired the building of Knossos in Minoan Create, we have no idea what that religion was or why it was able to inspire the creation of these structures for the rituals that were performed there, and why the people living there considered it necessary and worth all the effort!

Clearly, the god(s) (and it was probably a pantheon of gods, like the neighbouring Mesopotamians had later) had massive imaginary powers, giving the priesthood enormous powers of command and control, and elaborate rituals were considered necessary to appease or thank them. Yet we have no idea what those imaginary powers were, and whatever they were believed to have done, or not done in response to the rituals continued to be done or not done when the rituals ceased, their last believer died, and the monuments crumbled.

Rosa's Laws of Religion:This is a phenomenon that has been repeated time and again throughout human history as religions have come and gone together with their imaginary gods. No one now mourns at the graveside of these old dead gods.

The First Law of Theodynamics:

Gods can be created out of nothing and will disappear without trace.

No-one believes in Mars, Ra, Wodan, Thor or Saturn, and no-one says the rituals that were once essential to keep the seasons coming and going, the crops growing or the Nile flooding, and yet the seasons continue to come and go, the crops grow and the Nile still floods at the right time.

The prayers and rituals that once influenced these old gods are no longer needed, and the natural occurrences that were once 'obviously' caused or created by them are now just as 'obviously' caused or created by different gods in response to different prayers and rituals. And they will still occur when the current batch of gods have been consigned to the graveyard of the gods along with all the others.

What started me thinking in that line, was a recent article concerning the Arabian monuments in The Conversation by Melissa Kennedy, and Hugh Thomas, Lecturers in Archaeology at the University of Sydney. Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here

Enigmatic ruins across Arabia hosted ancient ritual sacrifices

Source: AAKSA / The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

A group of three mustatil and later Bronze Age funerary pendants on a rocky outcrop, southeast of AlUla County.

Source: AAKSA / The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

Melissa Kennedy, University of Sydney and Hugh Thomas, University of Sydney

Over the past five years, archaeologists have identified more than 1,600 monumental stone structures dotted across a swathe of Saudi Arabia larger than Italy. The purpose of these ancient stone buildings, dating back more than 7,000 years, has been a puzzle for researchers.

Our excavations and surveys reveal these were ritual structures, constructed by ancient herders and hunters who gathered to sacrifice animals to an unknown deity – perhaps in response to ancient climate change. The study is published in PLOS ONE today.

Desert discoveries

In the 1970s, the first archaeological surveys of northwest Saudi Arabia identified an ancient and mysterious rectangular structure. The sandstone walls of the structure were 95m long, and although it was determined to be unique, no further study of this unusual site was undertaken.

Over the following decades, airline passengers would see similar large “rectangles” dotted across the country. However, it was not until 2018 that one was excavated.

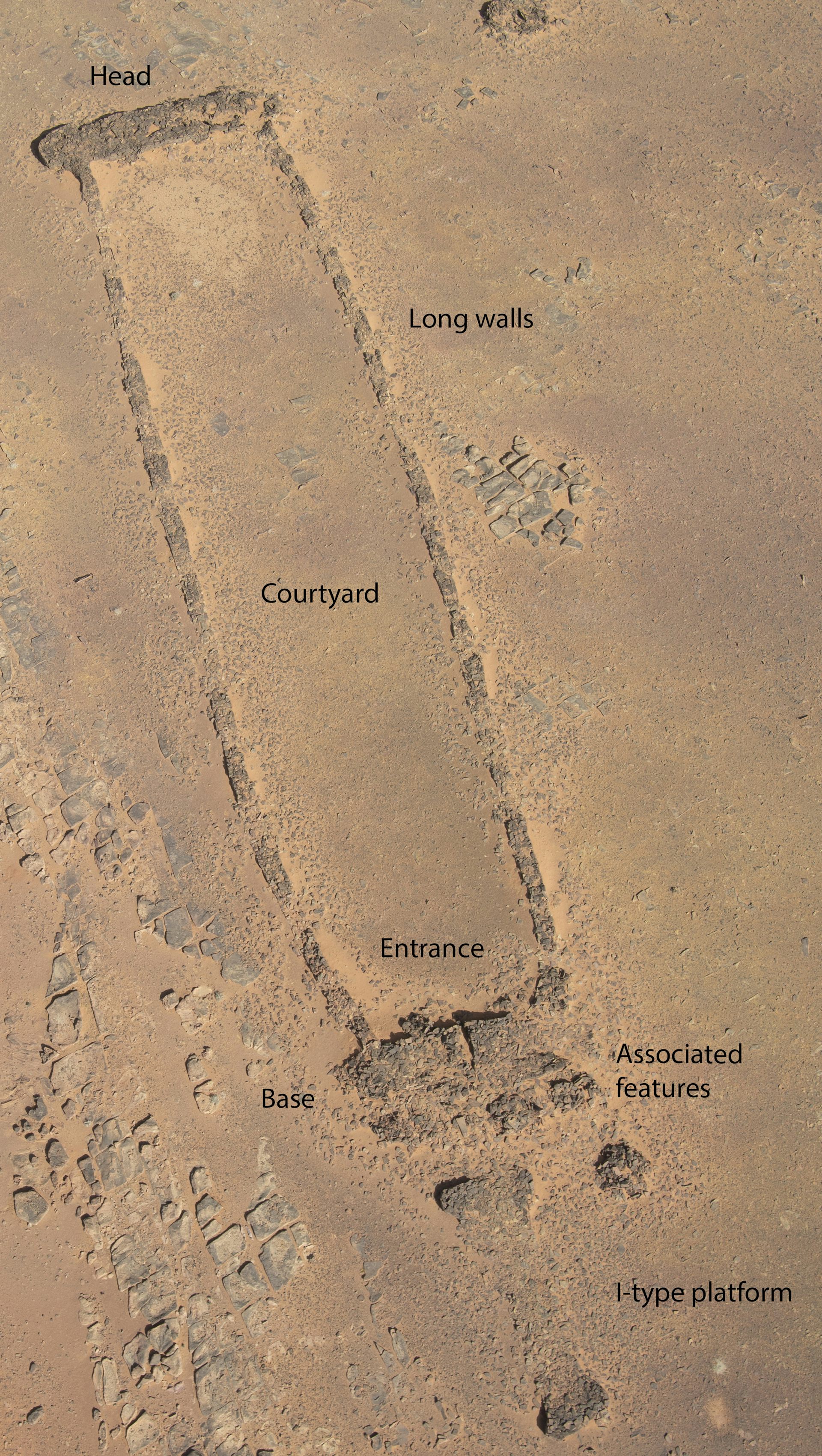

The main architectural features of a mustatil.

Credit: AAKSA /

The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

The smallest mustatils are around 20m long, while the largest are over 600m. Previous work by our team determined that all mustatils follow a similar architectural plan. Two thick ends were connected by between two to five long walls, creating up to four courtyards.

Access to the mustatil was through a narrow entrance in the base. There would then have been a long walk, perhaps in the form of a procession, to the “head”, where the main ritual activity took place.

Previous studies determined that the mustatils are at least 7,000 years old, dating to the end of the Neolithic period.

Cattle remains

In 2019–2020, we undertook excavations at a mustatil site called IDIHA-0008222. The structure, made from unworked sandstone, measures 140m in length and 20m in width.

Excavations in the head of the mustatil revealed a semi-subterranean chamber. Within this chamber were three large, vertical stones. We have interpreted these as “betyls”, or sacred standing stones which represented unknown ancient deities.

The excavated mustatil at IDIHA-0008222.

Credit: AAKSA / The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

Author provided

Surrounding these stones were well-preserved cattle, goat, and gazelle horns. The horns are so well preserved that much of what we find is the horn sheath, made of keratin – the same substance as hair and nails. We found only the upper cranial elements of these animals: the teeth, skulls, and horns. This suggests a clear and specific choice of offerings.

Further analysis suggests the bulk of these remains belonged to male animals and the cattle were aged between 2 and 12 years. Their slaughter would have formed a significant proportion of a community’s wealth, indicating these were high-value offerings.

Human remains

Current evidence suggests that the mustatils were in use between 5300 and 4900 BCE, a time when Arabia was green and humid. However, within a few generations, the ancient inhabitants of Saudi Arabia began to reuse these structures, this time to bury human body parts.

At IDIHA-0008222, a small structure had been built next to the mustatil. Inside were a partial foot, five vertebrae and several long bones.

Their placement suggests soft tissue was still present when they were buried. Forensic anthropologists were able to determine that the remains likely belonged to an individual aged between 30 and 40 years.

Our work at other mustatils has revealed similar deposits of human remains. Were these remains buried in attempt to claim ownership of the structure or some form of later ritual? These questions remain to be answered.

Pointing to water

The mustatils are changing how we view the Neolithic period not just in Arabia but across the Middle East. The sheer size of these structures and the amount of work involved in their construction suggests that multiple communities came together to create them, most probably as a form of group bonding.

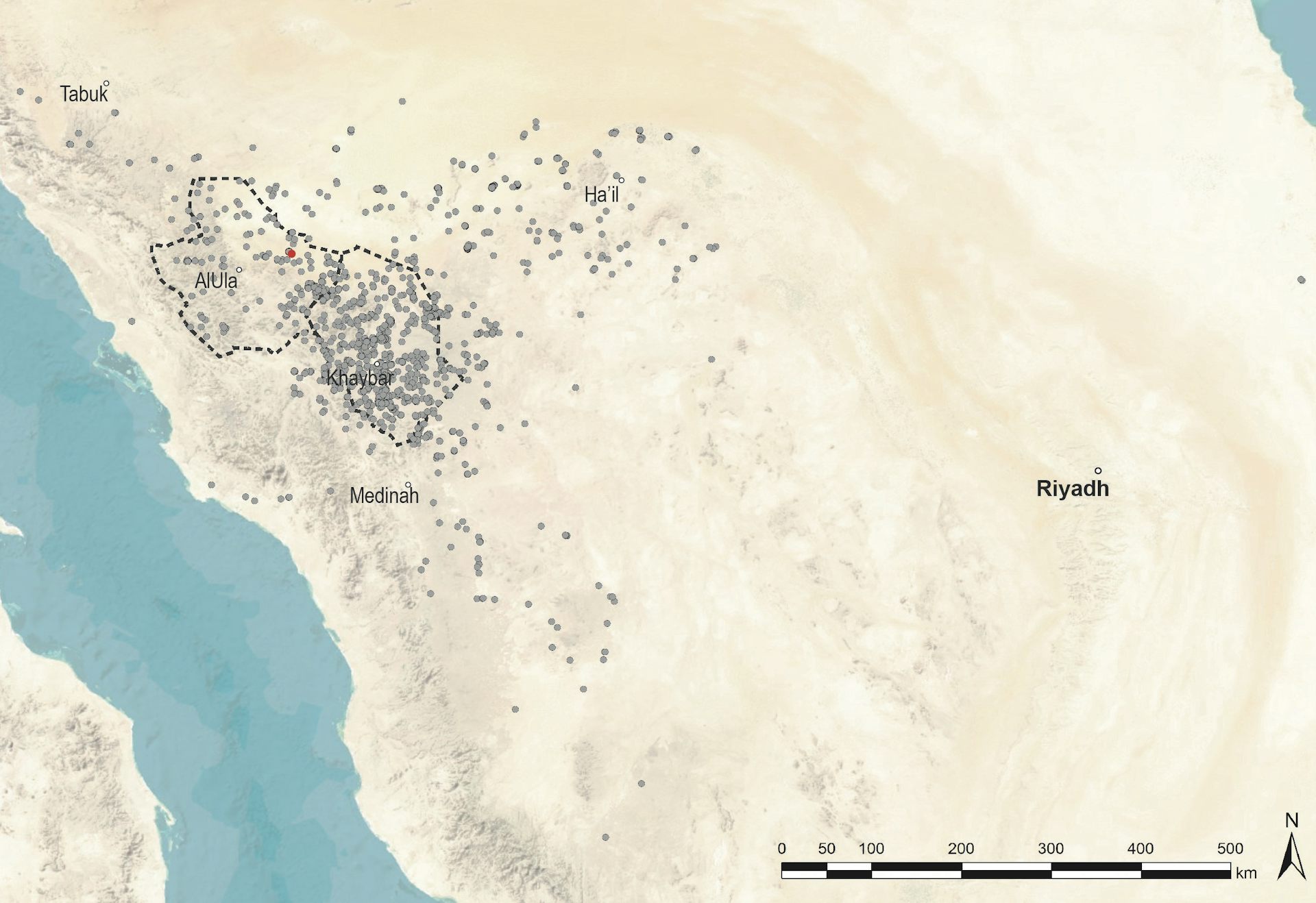

Moreover, their widespread distribution across Saudi Arabia suggests the existence of a shared religious belief, one held over a vast and un-paralleled geographic distance. Currently, fewer than ten mustatils have been excavated, so our understanding of these structures is still in its infancy.

Mustatil locations in Saudi Arabia, with the location of site IDIHA-0008222 marked in red.

Credit: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, the GIS User Community, USGS, NOAA /

AAKSA / The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

AAKSA / The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

While recording these structures after rain, we noted that almost all mustatils pointed towards areas that held water. Perhaps the mustatils were constructed and the animals offered to the god or gods to ensure the continuation of the rains and the fertility of the land.

The possibility remains that the mustatils were built in response to a changing climate, as the region became increasingly arid like it is today.

Two mustatil in Khaybar County pointing to standing water after rain.

Credit: AAKSA / The Royal Commission for AlUla,

Author provided

Author provided

We hope future excavations and analyses will reveal further insights into the life and death of the mustatils and the people who built them.

Melissa Kennedy, Lecturer in Archaeology, University of Sydney and Hugh Thomas, Lecturer in Archaeology, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The paper referred to in the article is published, open access in the online journal PLOS ONE:

AbstractIn the words of H.L.Mechen:

Since the 1970s, monumental stone structures now called mustatil have been documented across Saudi Arabia. However, it was not until 2017 that the first intensive and systematic study of this structure type was undertaken, although this study could not determine the precise function of these features. Recent excavations in AlUla have now determined that these structures fulfilled a ritual purpose, with specifically selected elements of both wild and domestic taxa deposited around a betyl. This paper outlines the results of the University of Western Australia’s work at site IDIHA-0008222, a 140 m long mustatil (IDIHA-F-0011081), located 55 km east of AlUla. Work at this site sheds new and important light on the cult, herding and ‘pilgrimage’ in the Late Neolithic of north-west Arabia, with the site revealing one of the earliest chronometrically dated betyls in the Arabian Peninsula and some of the earliest evidence for domestic cattle in northern Arabia.

Kennedy M, Strolin L, McMahon J, Franklin D, Flavel A, Noble J, et al. (2023)

Cult, herding, and ‘pilgrimage’ in the Late Neolithic of north-west Arabia: Excavations at a mustatil east of AlUla.

PLoS ONE 18(3): e0281904. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281904

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by PLoS. Open access

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Where is the graveyard of dead gods? What lingering mourner waters their mounds? There was a day when Jupiter was the king of the gods, and any man who doubted his puissance was ipso facto a barbarian and an ignoramus. But where in all the world is there a man who worships Jupiter today? And what of Huitzilopochtli? In one year—and it is no more than five hundred years ago—fifty thousand youths and maidens were slain in sacrifice to him. Today, if he is remembered at all, it is only by some vagrant savage in the depths of the Mexican forest. Huitzilopochtli, like many other gods, had no human father; his mother was a virtuous widow; he was born of an apparently innocent flirtation that she carried on with the sun. When he frowned, his father, the sun, stood still. When he roared with rage, earthquakes engulfed whole cities. When he thirsted he was watered with ten thousand gallons of human blood. But today Huitzilopochtli is as magnificently forgotten as Alien G. Thurman. Once the peer of Allah, Buddha and Wotan, he is now the peer of General Coxey, Richmond P. Hobson, Nan Patterson, Alton B. Parker, Adelina Patti, General Weyler, and Tom Sharkey…

But they have company in oblivion: the hell of dead gods is as crowded as the Presbyterian hell for babies. Damona is there, and Esus, and Drunemeton, and Silvana, and Dervones, and Adsalluta, and Deva, and Belisama, and Axona, and Vintios, and Taranuous, and Sulis, and Cocidius, and Adsmerius, and Dumiatis, and Caletos, and Moccus, and Ollovidius, and Albiorix, and Leucitius, and Vitucadrus, and Ogmios, and Uxellimus, and Borvo, and Grannos, and Mogons. All mighty gods in their day, worshiped by millions, full of demands and impositions, able to bind and loose—all gods of the first class, not dilettanti. Men labored for generations to build vast temples to them—temples with stones as large as hay-wagons. The business of interpreting their whims occupied thousands of priests, wizards, archdeacons, evangelists, haruspices, bishops, archbishops. To doubt them was to die, usually at the stake. Armies took to the field to defend them against infidels: villages were burned, women and children were butchered, cattle were driven off. Yet in the end they all withered and died, and today there is none so poor to do them reverence. Worse, the very tombs in which they lie are lost, and so even a respectful stranger is debarred from paying them the slightest and politest homage.

H.L. Menchen "Memorial Service".

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.