Slideshow code developed in collaboration with ChatGPT3 at https://chat.openai.com/

'An exciting possibility': scientists discover markedly different kangaroos on either side of Australia's dingo fence

If you change an organism's environment, the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection (TOE) predicts that the organism will evolve to fit into that changed environment. One such change could be the removal of an apex predator, as happened when humans erected the 'dingo fence', stretching more than 5,600 Km (about 3,500 miles) across Australia in the 1950, but was in a state of disrepair until 1975, which is thus the effective start of environmental isolation southeast of the fence.

The purpose of the fence was to protect domestic sheep from dingoes, Canis dingo, the wild Australian canid and only Australian placental mammal other than bats. Dingoes have been Australia's apex predator for some 10,000 years, maybe longer, so have been an important part of the ecosystem and the main, if not only, predator on red kangaroos, Osphranter rufus since then.

So, when wildlife to the southeast of the 'dingo fence' had their apex predator removed, the TOE predicts that there should be observable evolutionary change, and this is what a team of scientist led by Dr Rex Mitchel of the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia may have found when they studied the Red Kangaroos either side of the fence. Although, as they point out, evolutionary change in about 45 years, or about 17 red kangaroo generations, would be unusual and, with a limited dataset more work is needed to check that other factors are not the cause of the observed changes, for example, reduced stress in the protected area.

Four of the team: Vera Weisbecker, Associate Professor, Flinders University; Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Professor of Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University; Frédérik Saltré, Research Fellow in Ecology for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University, and Dr D Rex Mitchell, have written about their research in The Conversation.

Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

‘An exciting possibility’: scientists discover markedly different kangaroos on either side of Australia’s dingo fence

Image source: Shutterstock

Vera Weisbecker, Flinders University; Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Flinders University; Frédérik Saltré, Flinders University, and Rex Mitchell, Flinders University

Australia’s dingo fence is an internationally renowned mega-structure. Stretching more than 5,600 kilometres, it was completed in the 1950s to keep sheep safe from dingoes. But it also inadvertently protects some native species.

This makes the fence an unintentional experiment in the relationship between predators and prey. Our new research examined how the fence affects a favourite prey of the dingo: red kangaroos.

We found young kangaroos on the side exposed to dingoes grew more quickly than their protected counterparts. This has potentially big repercussions for the health of these juveniles.

The merits of the dingo fence are hotly debated, and there have been calls to pull it down or move it. That’s why we must seek a better understanding of how the fence affects the animals that live along it.

Australia’s dingo fence runs for more than 5,600 kilometres.

Image source: Shutterstock

The dingo fence, formally known as the “wild dog barrier fence”, runs through Queensland, New South Wales and South Australia. It protects sheep and cattle to the southeast.

Extensive fencing can fragment habitats and disrupt ecosystems. Maintaining the fence costs about A$10 million per year. For these and other reasons, some have suggested the fence be pulled down.

But how would removing the fence affect kangaroos that have lived without dingoes for up to 70 years? Our research sought to answer this question.

We assessed 166 red kangaroos from two isolated populations on either side of the fence in far northwest NSW. We did this using data collected as part of a licensed shooting program. We compared population size, age structure, sex ratio, growth rate and skull shape.

We expected kangaroos north of the fence – those hunted by dingoes – to differ from their dingo-free cousins to the south. That’s because their lives are more stressful, especially for young kangaroos and females that are killed by dingoes more often than adult males.

Female and young red kangaroos are targeted by dingoes.

Image source: Shutterstock

As anticipated, we found more young and female kangaroos in the dingo-protected population south of the fence. But the story is more complex than that.

Young kangaroos south of the fence, up to about the age of four years, grew more slowly than those in the north. They were substantially smaller and lighter than their dingo-exposed counterparts.

This raises an exciting possibility: that the growth of kangaroos south of the fence has slowed in the absence of the dingo threat.

But maybe there was just more plant food available in the north, where there are fewer kangaroos compared to the south. Was this the reason the northern kangaroos grew more quickly?

As it turns out, no. We assessed the vegetation on each side of the fence using a decade of satellite measurements. We found there was probably less, not more, food overall for kangaroos in the north compared to the south.

More detailed investigation is needed into whether the types of plants differed on each side of the fence. But our results suggest the different growth rates were driven by predators, not food availability.

There was probably less vegetation north of the dingo fence than in the south

Image source: Shutterstock

The differences between populations are even more striking considering the dingo fence in the area we studied was in disrepair until 1975. Before then, dingoes and kangaroos probably moved freely. So the changes we observed could have come about in as little as 17 kangaroo generations.

This would be unusually fast for an evolutionary adaptation. Instead, we suspect it’s the result of a more immediate response to the absence of dingoes, such as lower concentrations of stress-related hormones. These affect the health of mammals, and might have affected kangaroo growth rates in this case.

After about the age of four, the protected kangaroos had caught up and were the same size as their unprotected counterparts. But the unprotected kangaroos would have invested a lot more bodily resources into growing so quickly.

This would have left less energy for the animals to develop important functions such as their immune or reproductive systems. Or they might have had less fat reserves.

Conversely, protected kangaroos might have been healthier, or more fertile, because of their slower growth rates.

The research raises questions about how mammals respond to changes such as the absence of dingoes.

Image source: Shutterstock

Our study involved only a single sample at one point in time. But it’s the first to comprehensively assess differences in a dingo prey species on either side of a fence.

Our results provide an insight into how prey populations might fare if the dingo fence is removed. But the implications are potentially even broader.

We must now investigate whether other native mammal species share similar differences across the fence. If so, this could help us predict how animals elsewhere in Australia are coping with rapid environmental change.

Vera Weisbecker, Associate Professor, Flinders University; Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Professor of Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University; Frédérik Saltré, Research Fellow in Ecology for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University, and Rex Mitchell, Postdoctoral Fellow, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Abstract

Decommissioning the dingo barrier fence has been suggested to reduce destructive dingo control and encourage a free transfer of biota between environments in Australia. Yet the potential impacts that over a century of predator exclusion might have had on the population dynamics and developmental biology of prey populations has not been assessed. We here combine demographic data and both linear and geometric morphometrics to assess differences in populations among 166 red kangaroos (Osphranter rufus)—a primary prey species of the dingo—from two isolated populations on either side of the fence. We also quantified the differences in aboveground vegetation biomass for the last 10 years on either side of the fence. We found that the age structure and growth patterns, but not cranial shape, differed between the two kangaroo populations. In the population living with a higher density of dingoes, there were relatively fewer females and juveniles. These individuals were larger for a given age, despite what seems to be lower vegetation biomass. However, how much of this biomass represented kangaroo forage is uncertain and requires further on-site assessments. We also identified unexpected differences in the ontogenetic trajectories in relative pes length between the sexes for the whole sample, possibly associated with male competition or differential weight-bearing mechanics. We discuss potential mechanisms behind our findings and suggest that the impacts of contrasting predation pressures across the fence, for red kangaroos and other species, merit further investigation.

Mitchell, D Rex; Cairns, Stuart C; Körtner, Gerhard; Bradshaw, Corey J A; Saltré, Frédérik; Weisbecker, Vera (2023)

Differential developmental rates and demographics in Red Kangaroo (Osphranter rufus) populations separated by the dingo barrier fence

Journal of Mammology, gyad053. DOI: 10.1093/jmammal/gyad053

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by Oxford University Press. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

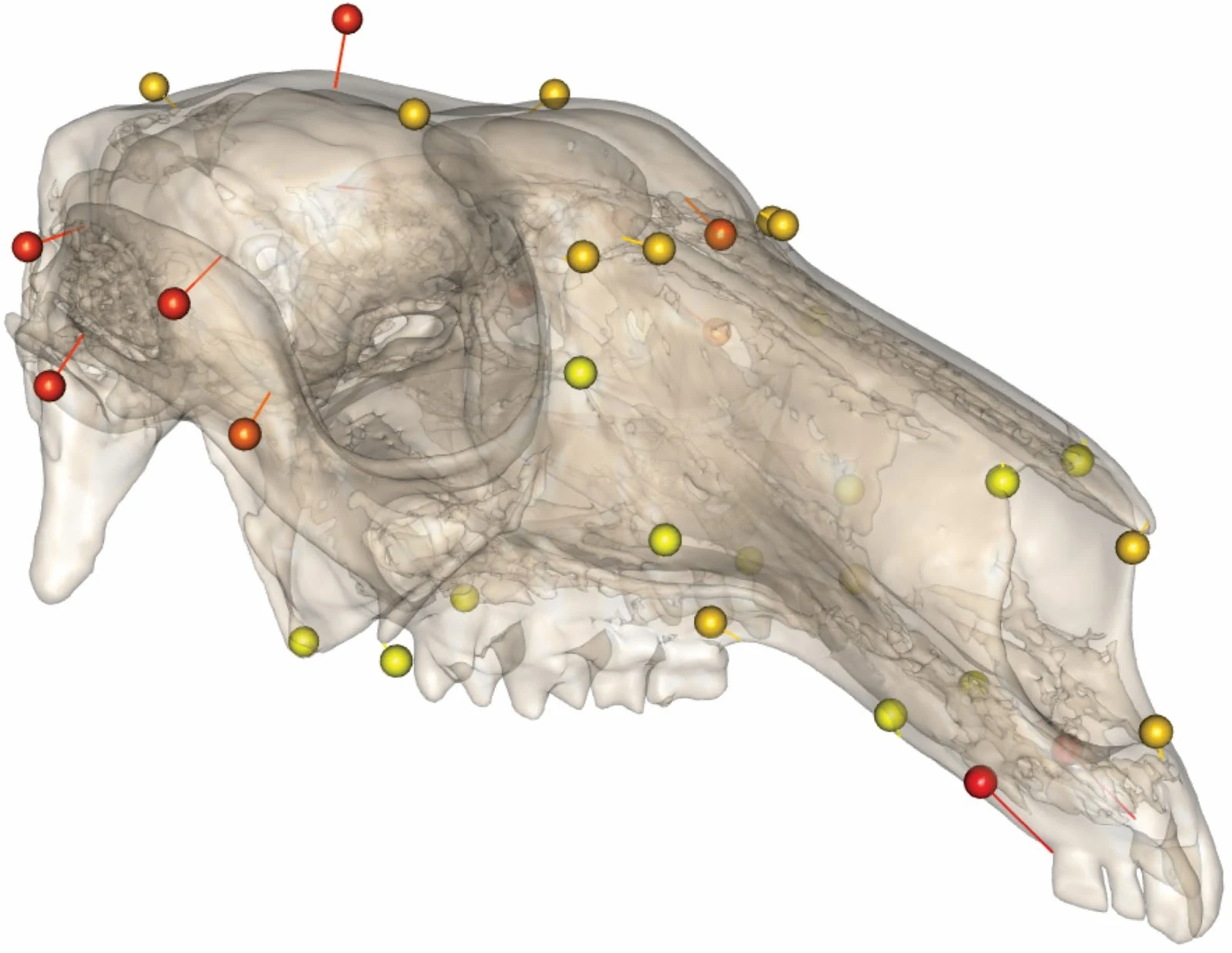

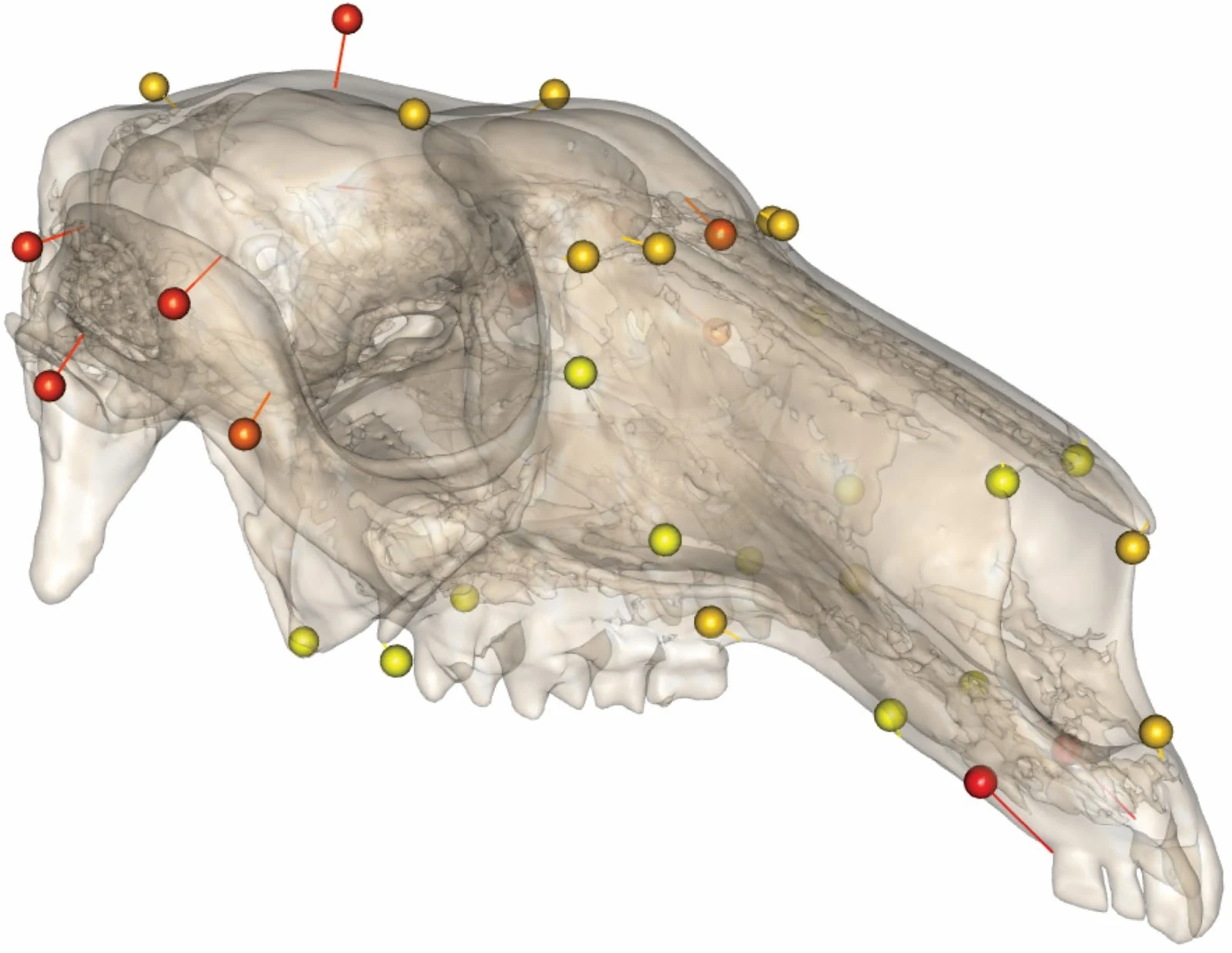

Fig 1.

Fig 4.

The dingo barrier fence extends from southeast Queensland to the Great Australian Bight in South Australia. The study location (black rectangle): Quinyambie and Mulyungarie stations are adjacent properties located on the western side of the South Australia–New South Wales border (black dotted line) and separated by the fence.

Fig 4.

Changes in cranial shape throughout ontogeny in Osphranter rufus. Orbs represent cranial shape predicted for younger individuals. Mesh represents shape predicted for older individuals. Relative braincase size and incisor size become smaller during growth.

What is now needed is detailed DNA analysis of the two populations because any differences would be definitive evolutionary change.

That should be a small crumb of comfort for creationists who must continue to hope that no such differences are found in red Kangaroos or other wildlife either side if the dingo fence, but I wonder how many of them would be prepared to bet their house on the probability of none being found.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.