In another of those casual refutations of the creation myth in the Bible, archaeologists have discovered a new species of pterosaur that flew in the skies of what if now the Isle of Skye, Scotland, about 165 million years before creationism's fabled god decided to magic up out of nothing, a small flat planet with a dome over it in the Middle East.

They are thought to have lived for some 5 million years between the late Early Jurassic up to the Late Jurassic.

The fossilised skeleton fills another of those gaps in the fossil record so beloved of creationist, where the scarcity of fossils meant that the evolution of pterosaurs was poorly understood. This fossil shows that all the main clades of pterosaurs had evolved before the end of the Early Jurassic and earlier than previously thought.

The team from the University of Bristol Natural History Museum, the University of Leicester, and the University of Liverpool have named the new species, Ceoptera evansae: Ceoptera from the Scots Gaelic word Cheò, meaning mist (a reference to the Gaelic name for the Isle of Skye, Eilean a’ Cheò, or Isle of Mist - Scots Gaelic is still widely spoken on Skye), and the Latin -ptera, meaning wing. Evansae honours Professor Susan E. Evans, for her years of anatomical and palaeontological research, in particular on the Isle of Skye.

What information is there on the Kilmaluag Formation of Skye, Scotland, particularly its age? The Kilmaluag Formation is a geological formation located on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. It is known for its rich fossil record, particularly of dinosaur footprints. The age of the Kilmaluag Formation is estimated to be from the Middle Jurassic period, specifically from the Bathonian to Callovian stages, which corresponds to approximately 166 to 163 million years ago. This age estimate is based on the presence of fossilized flora and fauna found within the formation, as well as radiometric dating techniques applied to volcanic ash layers associated with the formation. The Kilmaluag Formation is a significant site for understanding the paleoenvironment and biodiversity during the Middle Jurassic period in Scotland.

The new specimen, NHMUK PV R37110, was found on the north side of Glen Scaladal at Cladach a’Ghlinne (The shore of the Glen), a small beach that forms part of the coastline of Loch Scavaig, on the Strathaird Peninsula, Isle of Skye, Scotland, U.K, partially exposed in a large boulder close to the cliff face. The vertebrate-bearing horizons at this locality pertain to the Kilmaluag Formation (formerly the ‘Ostracod Limestone’) of the Great Estuarine Group, which crops out in several areas on Skye, Muck, and Eigg, but reaches its maximum thickness (up to 25 m) on the Strathaird Peninsula (Andrews, 1985; Barron et al., 2012; Harris & Hudson, 1980; Panciroli et al., 2020). Most of the vertebrate material known from the formation comes from the vicinity of Cladach a’Ghlinne.Many of the fossilised bone fragments were embedded within the rock so the team used CT scanning to visualise them.

The area is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), which is administered by Scottish Natural Heritage (formerly Scottish Nature), and the land is owned by the John Muir Trust: fieldwork and collection permits were obtained from both organizations and are on file at the Natural History Museum, London. Collection from the cliff faces is not permitted at this locality, but permission was granted to collect from fallen blocks on the wavecut platform.

The specimen was found partially exposed as a scatter of thin-walled bones on a large boulder situated a few meters from the cliff face at the northern-most edge of the beach (close to the small headland that separates Cladach a’Ghlinne from Camasunary Bay). The specimen was collected in several pieces using hand tools and a small angle-grinder and was reconstructed in the Conservation Centre of the NHMUK.

Creationists might like to ignore the reference to radiometric dating of volcanic ash because it will involve the U-Pb/zircon dating technique that terrifies them with its unarguable accuracy.

More detail is given in the team's abstract and introduction to their open access paper in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology:The time period that Ceoptera is from is one of the most important periods of pterosaur evolution, and is also one in which we have some of the fewest specimens, indicating its significance. To find that there were more bones embedded within the rock, some of which were integral in identifying what kind of pterosaur Ceoptera is, made this an even better find than initially thought. It brings us one step closer to understanding where and when the more advanced pterosaurs evolved.

Dr Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, Lead author

Palaeobiologist

School of Earth Sciences University of Bristol, Brisol, UKCeoptera helps to narrow down the timing of several major events in the evolution of flying reptiles. Its appearance in the Middle Jurassic of the UK was a complete surprise, as most of its close relatives are from China. It shows that the advanced group of flying reptiles to which it belongs appeared earlier than we thought and quickly gained an almost worldwide distribution.

Professor Paul Barrett, senior author

Merit Researcher Amphibians, and Birds Section, The Natural History Museum, London, UK

ABSTRACTPoints for creationists to ignore or try to misrepresent include the fact that this pterosaur was flying over what it now the Isle of Skye, about 165 million years before Earth existed, according to creationism's Bible-based mythology, as verified by U-Pb dating of volcanic zircons, and the fact that this find closes yet another gap in the fossil record and shows that the pterosaurs had diversified into the main clades earlier than previously thought.

The Middle Jurassic was a critical time in pterosaur evolution, witnessing the appearance of major morphological innovations that underpinned successive radiations by rhamphorhynchids, basally branching monofenestratans, and pterodactyloids. Frustratingly, this interval is particularly sparsely sampled, with a record consisting almost exclusively of isolated fragmentary remains. Here, we describe new material from the Bathonian-aged Kilmaluag Formation of Skye, Scotland, which helps close this gap. Ceoptera evansae (gen. et sp. nov.) is based on a three-dimensionally preserved partial skeleton, which represents one of the only associated Middle Jurassic pterosaurs. Ceoptera is among the first pterosaurs to be fully digitally prepared, and µCT scanning reveals multiple elements of the skeleton that remain fully embedded within the matrix and otherwise inaccessible. It is diagnosed by unique features of the pectoral and pelvic girdle. The inclusion of this new Middle Jurassic pterosaur in a novel phylogenetic analysis of pterosaur interrelationships provides additional support for the existence of the controversial clade Darwinoptera, adding to our knowledge of pterosaur diversity and evolution.

INTRODUCTION

Pterosaurs first appear during the Late Triassic and persist through to the K-Pg extinction (Barrett et al., 2008; Unwin, 2005; Witton, 2013). The clade includes taxa that fall into three principal morphotypes: ‘rhamphorhynchoids,’ a paraphyletic group of Late Triassic–Late Jurassic basally branching forms; pterodactyloids, a large clade of highly derived Late Jurassic to end-Cretaceous taxa; and ‘darwinopterans,’ Middle–Late Jurassic early-branching monofenestratans that appear to be intermediate between the other morphotypes (Lü et al., 2010). Darwinopterans have been interpreted as a paraphyletic group directly transitional to Pterodactyloidea (Lü et al., 2010), but the unity or otherwise of this clade, and the relationships of the taxa included within it, are controversial, undermining attempts to understand pterosaur evolutionary history (e.g., Wang et al., 2009, 2010.1, 2017).

The majority of pterosaur remains have been recovered from a handful of Mesozoic Konservat Lagerstätten, which are irregularly distributed in time and space (Barrett et al., 2008; Butler et al., 2009.1, 2013.1; Dean et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2014; Unwin, 2001; Upchurch et al., 2015; Wellnhofer, 1991; Zhou & Wang, 2010.2). While Lagerstätten have played a critical role in understanding pterosaur anatomy, functional morphology, and reproduction (Unwin, 2005; Wellnhofer, 1991; Witton, 2013), the potentially detailed insights they give into pterosaur evolutionary history can be biased, misleading, and difficult to interpret. For example, apparent peaks in pterosaur taxonomic diversity during the Late Jurassic (Sullivan et al., 2014; Wellnhofer, 1991; Witton, 2013) and mid-Early Cretaceous (Wellnhofer, 1991; Witton, 2013; Zhou & Wang, 2010.2) likely reflect the occurrence of multiple Lagerstätten in these intervals, rather than a true diversity signal (Butler et al., 2009.1, 2013.1; Dean et al., 2016).

This ‘Lagerstätten effect’ is exacerbated by the paucity of pterosaur finds in the temporal gaps between these windows of exceptional preservation, with the late Early–Middle Jurassic pterosaur fossil record, an interval of almost 20 Ma, being particularly poorly sampled (Barrett et al., 2008; Butler et al., 2009.1, 2013; Dean et al., 2016; Wellnhofer, 1991). The Taynton Limestone Formation (including the ‘Stonesfield Slates’) of Oxfordshire, U.K., has yielded the most abundant remains, but the bones from this unit are disarticulated, isolated, and often fragmentary, frustrating attempts to determine the species-richness of this assemblage (O’Sullivan & Martill, 2018). Other isolated remains have been reported from elsewhere in the Middle Jurassic of England (Oxford Clay; Barrett et al., 2008) and Scotland, which recently yielded Dearc, a three-dimensionally preserved, articulated rhamphorhynchine, and the proximal end of a tibia associated with caudal elements (Jagielska et al., 2022, 2023), as well as important records from Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, and China (Barrett et al., 2008). Moreover, several important deposits thought to have been of Middle Jurassic age have since been re-dated: the Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Argentina), which yielded Allkaruen (Codorniú et al., 2016.1), is now considered to be late Lower Jurassic (Cúneo et al., 2013.2) while the Tiaojishan Formation (NE China), which includes rhamphorhynchines, scaphognathines, anurognathids, darwinopterans, and basally branching pterodactyloids, has been dated as lowermost Upper Jurassic (Liu et al., 2012.1; Xu et al., 2016.2).

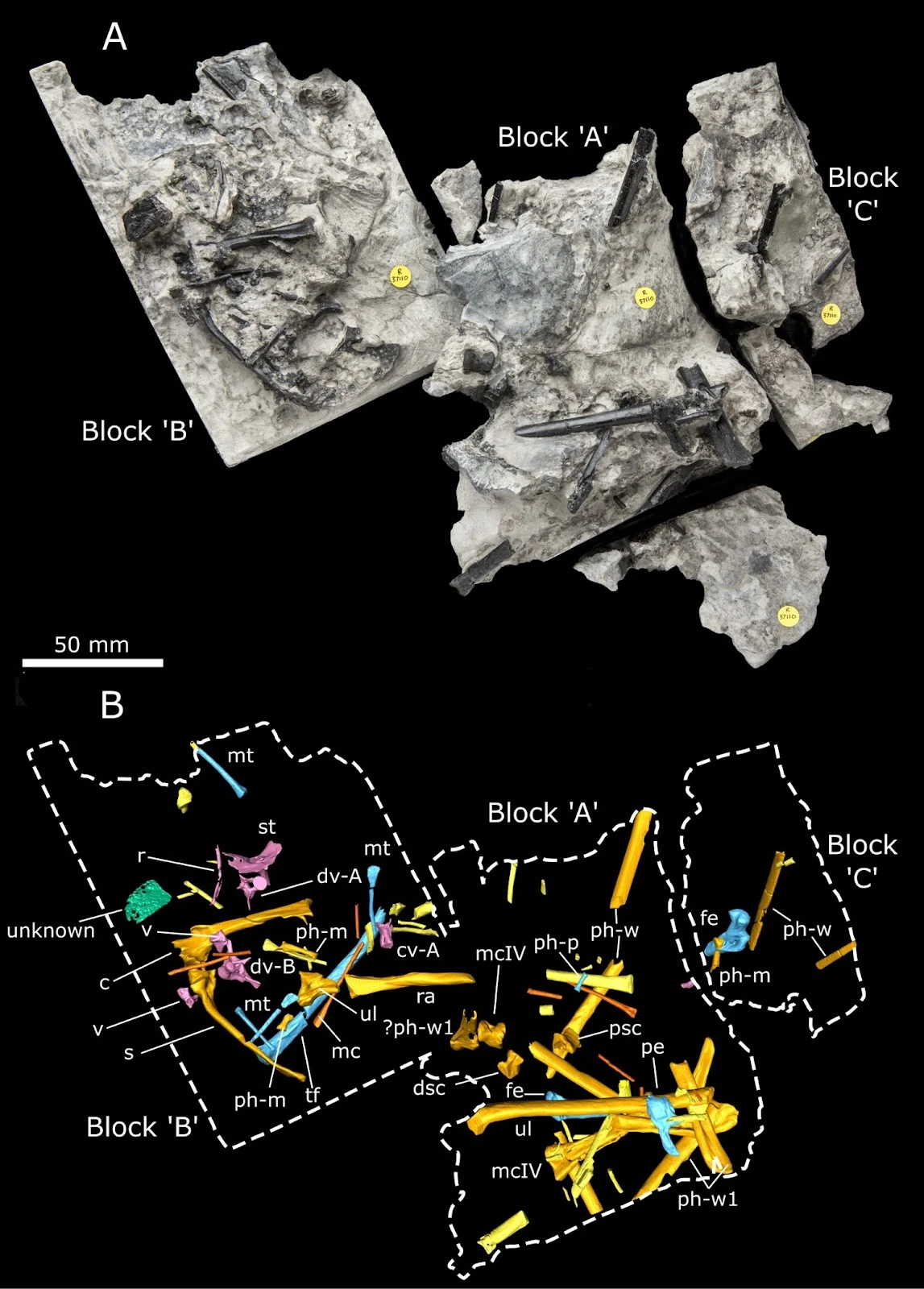

The rarity of Middle Jurassic pterosaurs and their incompleteness (only Dearc, a few associated remains of a second indeterminate pterosaur, also from Scotland [Jagielska et al., 2022, 2023], and a possible ?anurognathid from Mongolia [Bakhurina & Unwin, 1995] are known from multiple elements) severely hinders attempts to understand early pterosaur evolution. This problem is reflected in the lack of congruence between recently published pterosaur phylogenies, with little agreement on the compositions and/or likely times of origin of key clades such as Monofenestrata, Darwinoptera, and Pterodactyloidea (Baron, 2020.1; Dalla Vecchia, 2022.1; Jagielska et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2017.1). The recovery of associated skeletons, complete or otherwise, of Middle Jurassic pterosaurs is critical for resolving these issues and generating a clearer picture of pterosaur evolutionary history. Here, we describe a new, three-dimensionally preserved, partial pterosaur skeleton from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian: ∼168.3–166.1 Ma) of the Isle of Skye, Scotland. This is only the fourth associated skeleton of a Middle Jurassic pterosaur to be discovered to date. FIGURE 1. NHMUK PV R37110, the holotype of Ceoptera evansae, approximately as it was found (top) and by CT reconstruction with elements (bottom). Letters indicate the blocks as discussed in the text.

FIGURE 1. NHMUK PV R37110, the holotype of Ceoptera evansae, approximately as it was found (top) and by CT reconstruction with elements (bottom). Letters indicate the blocks as discussed in the text.

FIGURE 2. Reconstruction of the acetabulum and postacetabular process of the left pelvis of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in A, lateral, and B, medial views.

FIGURE 2. Reconstruction of the acetabulum and postacetabular process of the left pelvis of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in A, lateral, and B, medial views.

Abbreviations: a, acetabulum; dx, dorsal expansion; ic, ischium; pap, postacetabular process; re, recess.

FIGURE 3. The partially preserved right ulna of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in A, ventral, and B, dorsal views.

FIGURE 3. The partially preserved right ulna of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in A, ventral, and B, dorsal views.

Abbreviations: t, tubercle.

FIGURE 4. Complete left metacarpal IV of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in: A, anterior; B, posterior; and C, distal views.

FIGURE 4. Complete left metacarpal IV of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in: A, anterior; B, posterior; and C, distal views.

Abbreviations: dc, dorsal condyle; vc, ventral condyle; ve, ventral expansion.

FIGURE 5. Right femur of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), lacking a short section of the diaphysis, in A, C, anterior, B, D, posterior, and E, distal views. The proximal portion (A, B) is located in Block C while the distal portion (C–E) is located in Block B.

FIGURE 5. Right femur of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), lacking a short section of the diaphysis, in A, C, anterior, B, D, posterior, and E, distal views. The proximal portion (A, B) is located in Block C while the distal portion (C–E) is located in Block B.

Abbreviations: cf, collum femoralis; gr, groove; gt, greater trochanter; mc, medial condyle.

FIGURE 7. Dorsal vertebrae A (A, B) and B (C, D) of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in A, C, anterior and B, D, posterior views.

FIGURE 7. Dorsal vertebrae A (A, B) and B (C, D) of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), in A, C, anterior and B, D, posterior views.

Abbreviations: c, centrum; cf, capitular facet; ns, neural spine; prz, prezygopophysis; tf, tubercular facet; tp, transverse process.

FIGURE 8. Reconstruction of the right scapulocoracoid of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), made from CT scans in A, lateral and B, medial views. C, reveals a close-up of the expanded sub-triangular brachial flange of the coracoid, one of the diagnostic characters of this taxon.

FIGURE 8. Reconstruction of the right scapulocoracoid of Ceoptera evansae (NHMUK PV R37110), made from CT scans in A, lateral and B, medial views. C, reveals a close-up of the expanded sub-triangular brachial flange of the coracoid, one of the diagnostic characters of this taxon.

Abbreviations: acc, acrocoracoid process; afs, articular facet for sternum; bf, brachial flange; c, coracoid; cf, coracoid flange; gl, glenoid; s, scapula; sde, distal expansion of scapula. The top scale bar is for A and B.

Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, David M. Unwin, Andrew R. Cuff, Emily E. Brown, Lu Allington-Jones & Paul M. Barrett (2024)

A new pterosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Skye, Scotland and the early diversification of flying reptiles,

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2023.2298741

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by Taylor & Francis Group (Informa UK Ltd.) Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY NC-ND 4.0)

They should also ignore the fact that the team of palaeontologist showed no hint of abandoning the Theory of Evolution as the best model for explaining the discovery, despite the claims of creationist cult leaders that scientists are doing so in increasing numbers and the scientific consensus is moving in favour of a Bronze Age guess, complete with unevidenced supernatural entities and magic.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.