One of creationism's many problems is that being a counter-factual superstition it is easy to refute with facts. For example, trying to cling to the childish belief that the Universe and Earh are both between 6 and 10,000 years old, must be difficult in view of all the evidence of things happening on Earth before then - like people using fire in Tasmania 41,000 years ago.

But, as though to illustrate how creationism is not science but superstition, creationists have a knee-jerk response to that sort of news by simply shrugging their shoulders and declaring that the scientists have either lied, misunderstood the data or failed to recognise that their dating method must be wrong because it doesn't agree with creationists.

The evidence, of course, comes not only from dating the charcoal found in mud, which shows us that people used fire to clear the land, but the sudden change in the pollen found in the same mud at the same time as the charcoal appears, showing how the vegetation was destroyed by fire to be replaced with other flora. This was discovered by a team of researchers from the UK and Australia, who published their findings, open access, recently in the journal, Science, and explained it in a University of Cambridge, press release.

What information do you have about human migration to Australia and the island of Tasmania? Human migration to Australia and Tasmania is a fascinating chapter in human prehistory. Here's a summary:

Migration to Australia

- Timeframe:

- Modern humans are thought to have first migrated to Australia around 65,000 to 50,000 years ago, based on archaeological and genetic evidence.

- Route:

- Early humans likely travelled from Southeast Asia via a series of land bridges and short sea crossings, using the now-submerged Sahul Shelf, which connected Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania during periods of lower sea levels.

- These migrations occurred during times of lower sea levels, making the journey across the so-called "Wallace Line" (a biogeographic barrier) possible, albeit challenging.

- Cultural and Technological Adaptations:

- These early Australians were skilled in watercraft construction and navigation, evidenced by the need for seafaring capabilities to cross ocean gaps.

- Tools, rock art, and other cultural artifacts found across Australia demonstrate advanced adaptation to diverse environments, from arid deserts to coastal regions.

- Impact on Megafauna:

- The arrival of humans coincided with the extinction of many of Australia’s large megafauna, though this may have been influenced by climate changes and human hunting.

Migration to Tasmania

Both migrations showcase early humans' adaptability, innovation, and resilience in exploring and inhabiting new and challenging environments. Would you like more detailed information on specific aspects, like the archaeological sites or genetic studies?

- Timeframe:

- Humans reached Tasmania around 35,000 years ago, when Tasmania was connected to mainland Australia via the Bassian Plain during periods of low sea level.

- Isolation:

- Around 8,000 years ago, rising sea levels due to the end of the last Ice Age submerged the land bridge between Tasmania and mainland Australia, isolating the Tasmanian population.

- This isolation had profound effects on the culture and technology of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people, as they developed independently from the mainland.

- Cultural Distinctiveness:

- The Tasmanian Aboriginal people retained some technologies, such as stone tools, but abandoned others, such as fishing with hooks and nets, possibly due to environmental or resource availability factors.

- Historical Context:

- When European colonizers arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries, they encountered Tasmanian Aboriginal cultures that had evolved uniquely over thousands of years. Tragically, colonization led to violent conflict, cultural disruption, and dramatic population decline.

Some information about genetic studies would be interesting.

Genetic studies have provided profound insights into the migration of humans to Australia and Tasmania, helping to trace the origins, timelines, and adaptations of these ancient populations. Here’s what the genetic evidence tells us:

Genetic Evidence on Migration to Australia

- Ancestral Origins:

- Genetic analyses show that the ancestors of Aboriginal Australians diverged from other modern human populations around 70,000–50,000 years ago during the "Out of Africa" migration.

- They share ancestry with groups that migrated into Southeast Asia but formed a distinct lineage after separating from other populations.

- Single vs. Multiple Migrations:

- Evidence suggests a single major migration event brought humans to the Sahul region (the supercontinent comprising Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania).

- Subsequent genetic diversification occurred as populations spread across Australia and adapted to its varied environments.

- Connection to Denisovans:

- Aboriginal Australians and Papuans possess genetic material from Denisovans, an archaic human species. This indicates interbreeding occurred after modern humans entered Southeast Asia but before reaching Australia.

- Population Structure:

- Genetic studies reveal that Aboriginal Australians have remarkable regional diversity, suggesting that groups became locally adapted and remained largely isolated within Australia for tens of thousands of years.

- This is supported by evidence of deep genetic continuity between ancient and modern Aboriginal populations in specific regions.

Genetic Studies and Tasmania

- Isolation and Divergence:

- After the Bassian Plain was submerged around 8,000 years ago, the Tasmanian Aboriginal population became genetically isolated.

- This isolation led to unique genetic characteristics distinct from mainland Aboriginal Australians, though they share a common ancestry.

- Impact of Bottlenecks:

- The prolonged isolation of Tasmanians, combined with the small population size, likely caused a genetic bottleneck, reducing genetic diversity compared to mainland groups.

- Modern Implications:

- Sadly, the genocidal policies and diseases introduced during European colonization nearly annihilated the Tasmanian Aboriginal population, severely disrupting their genetic lineage.

- However, descendants of Tasmanian Aboriginal people survive today, preserving links to their ancient heritage.

Insights from Ancient DNA

- Lake Mungo 3 (Mungo Man):

- One of the oldest known human remains in Australia (~42,000 years old) was found in Lake Mungo.

- Ancient DNA extraction attempts from Mungo Man were inconclusive, but related research supports the deep genetic connection between ancient and modern Aboriginal Australians.

- Tools of Study:

- Techniques like mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and whole-genome sequencing have been instrumental in reconstructing migration routes and timing.

- Advances in ancient DNA technology continue to refine our understanding of these populations.

- Global Significance:

- Aboriginal Australians and their descendants represent one of the oldest continuous cultures on Earth, with genetic evidence underscoring their extraordinary longevity and adaptation.

Study uncovers earliest evidence of humans using fire to shape the landscape of Tasmania

Some of the first human beings to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, about 2,000 years earlier than previously thought.

A team of researchers from the UK and Australia analysed charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud to determine how Aboriginal Tasmanians shaped their surroundings. This is the earliest record of humans using fire to shape the Tasmanian environment.

Early human migrations from Africa to the southern part of the globe were well underway during the early part of the last ice age – humans reached northern Australia by around 65,000 years ago. When the first Palawa/Pakana (Tasmanian Indigenous) communities eventually reached Tasmania (known to the Palawa people as Lutruwita), it was the furthest south humans had ever settled.

These early Aboriginal communities used fire to penetrate and modify dense, wet forest for their own use – as indicated by a sudden increase in charcoal accumulated in ancient mud 41,600 years ago.

The researchers say their results, reported in the journal Science Advances, could not only help us understand how humans have been shaping the Earth’s environment for tens of thousands of years, but also help understand the long-term Aboriginal-landscape connection, which is vital for landscape management in Australia today.

Tasmania currently lies about 240 kilometres off the southeast Australian coast, separated from the Australian mainland by the Bass Strait. However, during the last ice age, Australia and Tasmania were connected by a huge land bridge, allowing people to reach Tasmania on foot. The land bridge remained until about 8,000 years ago, after the end of the last ice age, when rising sea levels eventually cut Tasmania off from the Australian mainland.

Australia is home to the world’s oldest Indigenous culture, which has endured for over 50,000 years. Earlier studies have shown that Aboriginal communities on the Australian mainland used fire to shape their habitats, but we haven’t had similarly detailed environmental records for Tasmania.

Dr Matthew Adeleye, lead author

Department of Geography

University of Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK.

The researchers studied ancient mud taken from islands in the Bass Strait, which is part of Tasmania today, but would have been part of the land bridge connecting Australia and Tasmania during the last ice age. Due to low sea levels at the time, Palawa/Pakana communities were able to migrate from the Australian mainland.

Analysis of the ancient mud showed a sudden increase in charcoal around 41,600 years ago, followed by a major change in vegetation about 40,000 years ago, as indicated by different types of pollen in the mud.

This suggests these early inhabitants were clearing forests by burning them, in order to create open spaces for subsistence and perhaps cultural activities,” said Adeleye. “Fire is an important tool, and it would have been used to promote the type of vegetation or landscape that was important to them.

Dr Matthew Adeleye.

The researchers say that humans likely learned to use fire to clear and manage forests during their migration across the glacial landscape of Sahul – a palaeocontinent that encompassed modern-day Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea and eastern Indonesia – as part of the extensive migration out of Africa.

As natural habitats adapted to these controlled burnings, we see the expansion of fire-adapted species such as Eucalyptus, primarily on the wetter, eastern side of the Bass Strait islands.

Dr Matthew Adeleye.

Burning practices are still practiced today by Aboriginal communities in Australia, including for landscape management and cultural activities. However, using this type of burning, known as cultural burning, for managing severe wildfires in Australia remains contentious. The researchers say understanding this ancient land management practice could help define and restore pre-colonial landscapes.These early Tasmanian communities were the island’s first land managers,” said Adeleye. “If we’re going to protect Tasmanian and Australian landscapes for future generations, it’s important that we listen to and learn from Indigenous communities who are calling for a greater role in helping to manage Australian landscapes into the future.

Dr Matthew Adeleye.

The research was supported in part by the Australian Research Council.

Reference:

AbstractFor creationists trying to maintain the delusion that their magic invisible friend created everything just a few thousand years ago, with them in mind, trying to ignore this sort of evidence that Earth is very much older and has had humans living on it for hundreds of thousands of year must be like trying to sweep a tsunami back with a hand broom. One has to admire their stupidity in all its hideous glory.

The establishment of Tasmanian Palawa/Pakana communities ~40 thousand years ago (ka) was achieved by the earliest and farthest human migrations from Africa and necessitated migration into high-latitude Southern Hemisphere environments. The scarcity of high-resolution paleoecological records during this period, however, limits our understanding of the environmental effects of this pivotal event, particularly the importance of using fire as a tool for habitat modification. We use two paleoecological records from the Bass Strait islands to identify the initiation of anthropogenic landscape transformation associated with ancestral Palawa/Pakana land use. People were living on the Tasmanian/Lutruwitan peninsula by ~41.6 ka using fire to penetrate and manipulate forests, an approach possibly used in the first migrations across the last glacial landscape of Sahul.

INTRODUCTION

The establishment of ancestral Tasmanian Palawa/Pakana communities is the earliest evidence of human migrations into temperate latitude regions in the Southern Hemisphere. The oldest archaeological evidence of human occupation in Tasmania (Aboriginal given name: Lutruwita) is from excavated sediment layers in Warreen Cave (1) and Parmerpar Meethaner rock shelter (2), with the calibrated radiocarbon dates of 39,924 ± 1130 years and 38,680 ± 1400 years, respectively. Lutruwita was isolated from the mainland of Australia by high sea levels for much of the interval between 135 and 43 thousand years ago (ka), with the first sustained land bridge of the last glacial cycle occurring between 43 and 37 ka (3). Palawa/Pakana communities were able to traverse the partially exposed eastern Bassian Land Bridge to enter Lutruwita at this time (1–4). The land bridge became isolated from the Australian mainland as a result of rising sea levels during the early to mid-Holocene (3). While early evidence for the occupation of Lutruwita by Palawa/Pakana people is well documented through the archaeological record (1, 2, 5), the nature of fire use and effects on vegetation and fauna (including megafauna) remains speculative (2, 5) and at times contentious (6, 7). This is partly due to the scarcity of high-resolution paleoecological data that span the period between 50 and 40 ka in the region. Paleoecological records from the Australian mainland suggest that the arrival of Aboriginal peoples on the continent at least ~50 ka (8–13) was accompanied by changes in the biotic environment, including burning of vegetation and the replacement of closed woody vegetation by open vegetation communities, as well as the decline and extinction in megafaunal population (6, 14–18). Landscape management practices using fire are evident in Lutruwita at least after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (19) and apparent in paleoenvironmental records from northern and eastern Australia during the past 11,000 years (20, 21). Given existing evidence documenting millennia of burning practices in mainland Australia (20–22), we would expect landscape burning to accompany the arrival of people in Lutruwita.

Our goal in this study was to use two well-dated deep sedimentary records: Emerald Swamp and laymina paywuta (Palawa meaning: lagoon from a long time ago) situated at the western and eastern extremes of the Bass Strait (Three Hummock Island and Clarke Island/lungtalanana; Figs. 1 and 2) to reconstruct past environmental change and landscape changes associated with human arrival. Three Hummock Island is situated in the presently wet (annual average rainfall, ~939 mm) western side of Bass Strait, and lungtalanana is on the drier (annual average rainfall, ~616 mm) eastern side. These long-term records provide a unique opportunity to understand the interplay of past climates across the Pleistocene land bridge (23), including floristic and fire-regime changes associated with the earliest evidence for people within Lutruwita in two contrasting bioclimatic zones of this landscape (dry and wet temperate) with millennia of reversing precipitation gradients (24). In the context of previous research from mainland Australia, we expect that Aboriginal arrival in Lutruwita was also accompanied by a shift in fire regimes as a result of an additional source of fire ignitions—namely, people (hypothesis 1). We also expect the greatest plant species turnover (measured by beta diversity) following the first evidence for human arrival to have occurred in the then wetter landscapes where more fire-sensitive plants would have been common compared to the then drier landscapes where plant assemblages were likely more adapted to fires (hypothesis 2). Increased burning by people would differentially disadvantage the fire-sensitive species in wet environments compared to the fire-tolerant species from drier and more naturally fire-prone environments. Fig. 1. Climate and vegetation of study area.

Fig. 1. Climate and vegetation of study area.

Key climatic drivers (A) and annual rainfall distribution across Lutruwita/Tasmania (B), as well as vegetation and fire return interval of study area (60) (C and D)—Three Hummock Island and lungtalanana/Clarke Island in Bass Strait, Lutruwita. Maps [(B) to (D)] were created using LISTmap (60). Key sites later mentioned in the text are shown as well, including the site of climatic records (marine core 2611 and Fr1/94-GC3) offshore southern Australia (33) and southeast Lutruwita (28), existing dated pollen records spanning the past 30,000 to 75,000 years in Lutruwita from Lake Selina (38), offshore western Lutruwita—core SO 36-7SL (34) and Crystal Lagoon on truwana/Cape Barren Island (40), and the two archaeological sites containing the earliest evidence (~40 ka) of human occupation (Warreen Cave and Parmerpar Meethaner rock shelter) in Lutruwita (1). Fig. 2. Site age-depth models.

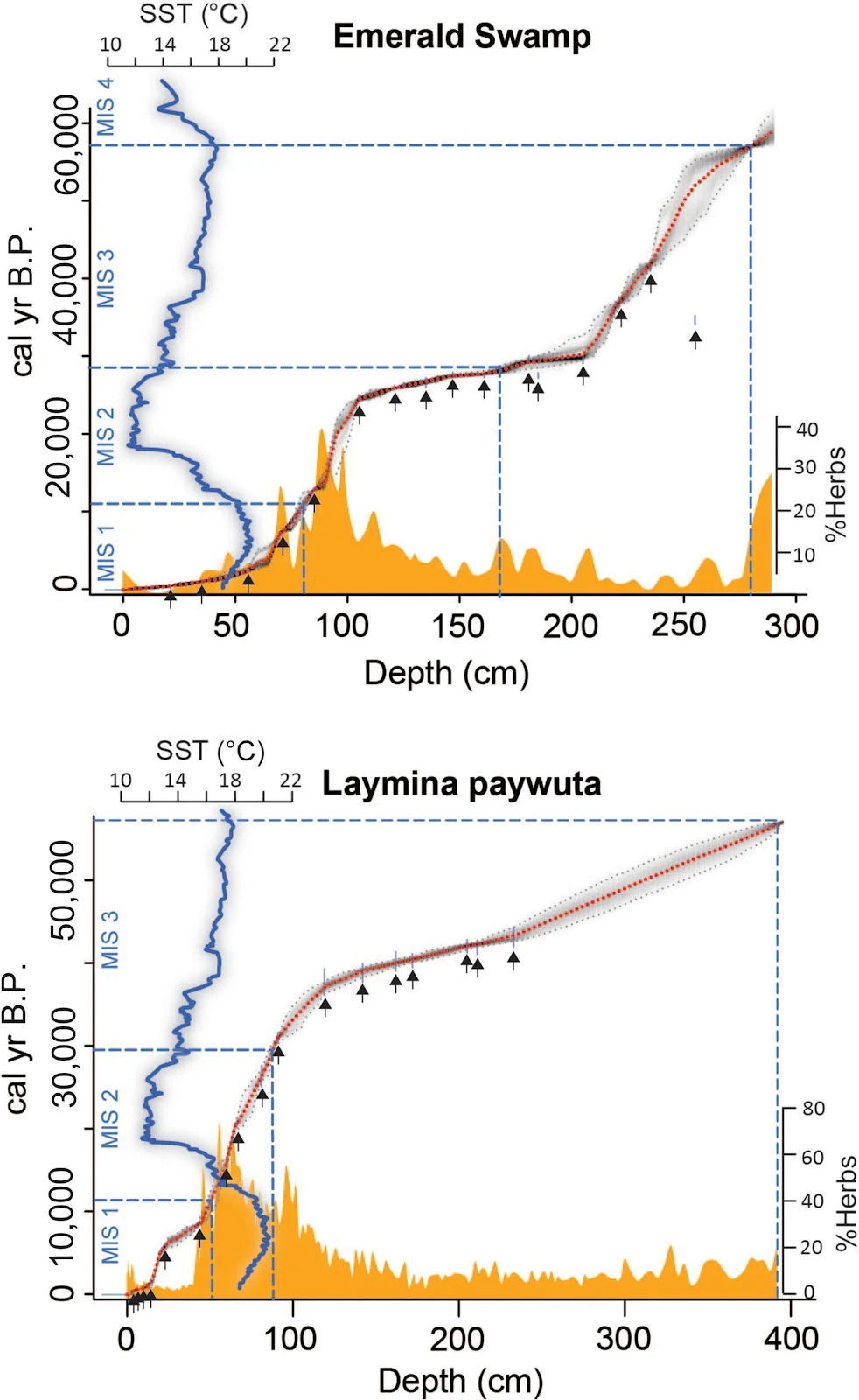

Fig. 2. Site age-depth models.

Emerald Swamp and laymina paywuta age-depth model showing calibrated (purple lines/black arrows) radiocarbon dates, 95% confidence intervals of calibrated range (light gray), and single model based on the weighted mean age for each depth (red curve). cal yr B.P., calendar years before the present. See table S1 and fig. S1 for radiocarbon date results and full Bacon age-depth model output. The relative abundance of herbaceous pollen (yellow) for both sites and sea surface temperatures (SSTs; blue) for southern Australia (33) used in supporting the identification of the marine isotope stages (MISs) is also shown.Matthew A. Adeleye et al.

Landscape burning facilitated Aboriginal migration into Lutruwita/Tasmania 41,600 years ago.

Sci. Adv. 10, eadp6579 (2024). DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adp6579

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by American Association for the Advancement of Science. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.