Reading the genome and understanding evolution: Symbioses and gene transfer in leaf beetles

Creationists who have been fooled by the disinformation pumped out by the Discovery Institute, especially by William Dembski, believe that the only way an organism can gain new genetic information is by being given it, pre-prepared, by a magic intelligent designer, who has the magical power to assemble new DNA in just the right order and insert it into a species' genome, by a mysterious process that neither Dembski, nor one of his co-misinformers, are willing to explain.

This, of course, ignores the scientific evidence that new genetic information can be acquired by a species in several different ways, not the least of which is by horizontal gene transfer from another species, as researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, the Max Planck Institute of Biology in Tübingen, Germany, and a consortium of international scientists have just shown in respect of the leaf beetles, one of the most successful group of beetles with more than 50,000 different species worldwide.

What information do you have on leaf beetles and their symbiotic relationship with bacteria? Leaf beetles (family Chrysomelidae) have fascinating symbiotic relationships with bacteria that play crucial roles in their biology, particularly in nutrition and defence. Here’s a detailed overview:The researcher’s findings are published open access in Current Biology and in a Max Plank Institute for Chemical Ecology news item:

Nutritional Symbiosis

- Plant Cell Wall Digestion:

Many leaf beetles feed on plants that are rich in cellulose and other complex carbohydrates. Symbiotic bacteria in their gut or specialized organs help break down these compounds, allowing the beetles to access nutrients that would otherwise be indigestible.- Amino Acid Supplementation:

Leaf beetles often feed on nutrient-poor plant tissues, such as leaves, which can lack essential amino acids. Symbiotic bacteria can synthesize these amino acids, supplementing the beetle's diet.- Specialized Organs:

Some leaf beetles have developed specialized structures, such as bacteriomes, to house symbiotic bacteria. These organs provide a stable environment for the bacteria, which in turn benefit the beetle by producing essential nutrients.

Defensive Symbiosis

- Chemical Defence:

Symbiotic bacteria in some leaf beetles produce defensive compounds that protect the beetles from predators and pathogens. For example, certain bacteria synthesize toxic or repellent chemicals that deter predators.- Egg Protection:

In some cases, symbiotic bacteria are transferred to the beetle's eggs, where they produce antimicrobial compounds to protect the eggs from fungal or bacterial infections.

Evolutionary Insights

- Vertical Transmission:

Many leaf beetles pass their symbiotic bacteria directly to their offspring, ensuring the continuity of the relationship. This vertical transmission has led to long-term co-evolution between beetles and their bacterial partners.- Genomic Integration:

In some cases, the symbiotic relationship has become so intimate that the bacterial genome is significantly reduced, retaining only the genes necessary for its role in the beetle's biology.- Diversity of Symbionts:

Different groups of leaf beetles harbours distinct bacterial symbionts, reflecting their diverse diets and ecological niches.

Research Highlights

- Cassida rubiginosa: A study on this species showed that its gut microbiota plays a key role in breaking down plant secondary metabolites, such as glucosinolates, which are toxic to many herbivores.

- Crioceris asparagi: This asparagus beetle harbours’ bacteria that produce toxic compounds to deter predators.

Significance

The symbiotic relationships between leaf beetles and bacteria highlight the importance of microbial partners in enabling insects to exploit challenging ecological niches. These partnerships have profound implications for understanding insect evolution, adaptation, and potential applications in pest management.

How leaf beetles found the key to digesting plants better with the help of bacteria

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, the Max Planck Institute of Biology in Tübingen, Germany, and a consortium of international scientists explored the evolutionary success of leaf beetles, the most diverse herbivores on Earth. They showed that symbioses with bacteria have evolved repeatedly and independently in different beetle lineages, and contribute significantly to the efficient digestion of plant food. These symbiotic relationships provide clues as to how genetic material was exchanged between bacteria and beetles. Key findings highlight the role of horizontal gene transfer, the incorporation of foreign bacterial genetic material into the beetle genome, which is thought to be the result of earlier symbioses. Overall, the study emphasizes the importance of microbial partnerships and genetic exchange in shaping the dietary adaptations of leaf beetles, which facilitated the evolutionary success of leaf beetles.

With more than 50,000 described species, the leaf beetle family is distributed worldwide and represents about a quarter of the species diversity of all herbivores. Leaf beetles can be found to feed on almost all plant groups. They live in the rhizosphere, the canopy and even underwater. Many leaf beetles, such as the Colorado potato beetle, are notorious pests. Their species richness and global distribution highlight their evolutionary success, which is particularly astonishing given that leaves are a difficult food source to digest and provide unbalanced nutrients.

Researchers from the Department of Insect Symbiosis at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena and the Mutualisms Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for Biology in Tübingen, Germany, have now asked how leaf beetles have overcome these dietary challenges throughout evolution. Do different leaf beetle species use the same strategy, or have they found other ways to achieve their nutritional goal?

Understanding the role of foreign genetic material

Almost all leaf beetles have incorporated foreign genetic material into their genome, which is responsible for the production of enzymes necessary to digest plant cell wall components. For example, pectinases are enzymes that break down pectins – indigestible dietary fibers for humans, but metabolized by many bacteria. Approximately half of the species of leaf beetles live in close association with symbiotic bacteria. These symbionts provide the beetles with important digestive enzymes to help them break down food components. They often also provide the beetles with vitamins and essential amino acids.

The researchers know from their own previous studies that the beetles use both pectinases from their own genome and those encoded by symbionts.

With the support of national and international colleagues, the team carried out genome and transcriptome analyses of 74 leaf beetle species from around the world. Through this comparative analysis across all leaf beetle subfamilies, the researchers could understand how the current distribution of the beetle's enzymes and symbiont-encoded enzymes has evolved.These digestive enzymes are essential for the beetles' survival. However, we only have a fragmentary understanding of which beetle species need symbiotic bacteria for digestion, which do not, and where the beetles' pectinases come from. We wanted to reconstruct the evolutionary scenarios that led to today's distribution patterns through comparative studies of all leaf beetle groups.

Roy Kirsch, first author

Department of Insect Symbiosis

Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology

Jena, Germany.

We were also able to demonstrate that horizontal gene transfer, a phenomenon that describes the incorporation of foreign genes from bacteria into the genome, is quite common in leaf beetles. Both symbiosis and horizontal gene transfer have strongly influenced the evolution of insects.

Roy Kirsch

The figure shows how beetles acquire pectinases, enzymes that are necessary to break down pectins, important components of the plant cell wall, through both horizontal gene transfer and symbiosis with bacteria. The acquisition of these enzymes enables leaf beetles to exploit a new dietary niche.

The figure shows how beetles acquire pectinases, enzymes that are necessary to break down pectins, important components of the plant cell wall, through both horizontal gene transfer and symbiosis with bacteria. The acquisition of these enzymes enables leaf beetles to exploit a new dietary niche.

From: Kirsch et al., Current Biology 2025.

Created in BioRender. Kirsch, R. (2024)

https://BioRender.com/l84e681

Dynamic evolution of pectinases

The analyses also revealed that the vast majority of the beetle species use either their own pectinases, acquired through horizontal gene transfer, or the pectinases of their bacterial symbionts. However, beetle and symbiont pectinases never occurred together in any beetle species.

The results of the study show that the evolution of pectinases is dynamic and characterized by the alternation of horizontal gene transfer and symbiont uptake.

The binary distribution of beetles encoding pectinases within their genomes versus those acquiring them symbiotically remains one of the most striking findings from the study. Such a pattern raises additional questions concerning how horizontal gene transfer and symbiosis have shaped the way beetles consume and process foliage, and the trade-offs associated with outsourcing a key metabolic trait.

Hassan Salem, co-corresponding author

Mutualisms Research Group

Max Planck Institute for Biology

Tübingen, Germany.A pathway to evolutionary successYou can imagine this process as follows: When a symbiosis is established, a beetle pectinase from a previous horizontal gene transfer is replaced by a symbiont pectinase. The advantage of incorporating a symbiont is that its pectinase may have new activities or be more efficient, and the symbiont may also provide additional benefits, such as producing other digestive enzymes or essential nutrients. The beetle's own pectinase gene is no longer needed and is lost during evolution. As the symbiotic interaction progresses, the symbiont's pectinase gene may be transferred into the beetle's genome and the symbiont may be lost, but this process needs to be studied in more detail.

Martin Kaltenpoth, co-corresponding author

Department of Insect Symbiosis

Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology

Jena, Germany.

The results show how repeated horizontal gene transfer and the establishment of symbioses with bacteria enabled leaf beetles to rapidly adapt to a plant-based diet, contributing to their remarkable evolutionary success.

HighlightsIt doesn't need a genius to work out how this overly-complicated system could have been made much simpler if intelligently designed to give the beetles the genes they need to digest the food they were 'designed' to eat. But evolution isn't an intelligent process - which is how we can tell that this system evolved and was not intelligently designed.Summary

- Genomics and transcriptomics resolve the phylogeny of leaf beetle subfamilies

- Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (PCWDEs) show a dynamic evolutionary history

- Multiple symbiont acquisitions and horizontal gene transfers contributed new PCWDEs

- Symbiosis and HGT expanded beetles’ digestive repertoires, fueling their success

Beetles that feed on the nutritionally depauperate and recalcitrant tissues provided by the leaves, stems, and roots of living plants comprise one-quarter of herbivorous insect species. Among the key adaptations for herbivory are plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (PCWDEs) that break down the fastidious polymers in the cell wall and grant access to the nutritious cell content. While largely absent from the non-herbivorous ancestors of beetles, such PCWDEs were occasionally acquired via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or by the uptake of digestive symbionts. However, the macroevolutionary dynamics of PCWDEs and their impact on evolutionary transitions in herbivorous insects remained poorly understood. Through genomic and transcriptomic analyses of 74 leaf beetle species and 50 symbionts, we show that multiple independent events of microbe-to-beetle HGT and specialized symbioses drove convergent evolutionary innovations in approximately 21,000 and 13,500 leaf beetle species, respectively. Enzymatic assays indicate that these events significantly expanded the beetles’ digestive repertoires and thereby contributed to their adaptation and diversification. Our results exemplify how recurring HGT and symbiont acquisition catalyzed digestive and nutritional adaptations to herbivory and thereby contributed to the evolutionary success of a megadiverse insect taxon.

Introduction

The diversification of land plants and insects is rooted in the terrestrialization of both lineages from aquatic ancestors, the subsequent evolution of herbivory in insects, and reciprocal antagonism between plants and insects.1 The working mechanistic hypothesis is that plant-herbivore coevolution led to their diversification in an arms race between ever-changing plant defenses and herbivores’ counter-adaptations mediating detoxification, resistance, or tolerance.2,3,4 In addition to specialized defense metabolites, all plants share the presence of a cell wall that is composed of recalcitrant polysaccharides. Polymers such as pectin and cellulose are implicated in plant growth, structural stability, and protection against biotic and abiotic stresses.5 While the importance of being able to digest the plant cell wall (PCW) has been recognized for herbivorous mammals and insects,6 the evolutionary dynamics of the underlying enzymatic capabilities are not fully resolved.

Herbivorous beetles contribute 25% to the total diversity of herbivorous animals.7 Among beetles, the Phytophaga—which encompass leaf beetles, weevils, and longhorned beetles—represent the most successful animal radiation, with about 140,000 described species.8 The presence of specific digestive capabilities, particularly PCW-degrading enzymes (PCWDEs), combined with low extinction rates over long evolutionary timescales, likely contributed to their species richness.9 PCWDEs are an assemblage of carbohydrate-active enzyme families, especially glycoside hydrolases (GHs), that target polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin10 and thereby aid the degradation of the PCW, granting access to the nutritious cell content.11 Apart from GH family 9 (GH9) cellulases that are ancestral to multicellular animals,12 all other known PCWDEs in beetles were either acquired by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from bacteria or fungi,9,13,14,15 or are provided by microbial symbionts.16,17,18 However, the contribution of HGT and microbial symbiosis to the PCWDE arsenals of herbivorous beetles and their impact on the beetles’ evolutionary success remain incompletely understood.

Here, we provide the first comprehensive analysis of the evolution of host- and symbiont-encoded PCWDEs across all recognized subfamilies19 of the megadiverse leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae; >40,000 described species20). In doing so, we assess the importance of HGT and symbiosis as sources for novel PCWDE genes across a beetle lineage comprising important agricultural pests as well as biocontrol agents. Based on a broad set of transcriptomes (74 species) and phylogenetically representative genomes (19 species) (Tables S1 and S2), we reconstruct a robust phylogeny that resolves most of the outstanding uncertainties about the subfamily relationships within leaf beetles. Functional annotation and comparative analyses of beetle and symbiont genomes, along with the localization of symbionts across life stages by fluorescence in situ hybridization, yield a diverse complement of beetle- and symbiont-encoded PCWDEs. Their evolutionary histories reveal a complex pattern of gene and symbiont gains and losses. These events accompanied important dietary transitions along the 180 million years of coevolution with their host plants and likely contributed to the enormous success of one of the most diverse taxa of herbivores on the planet.

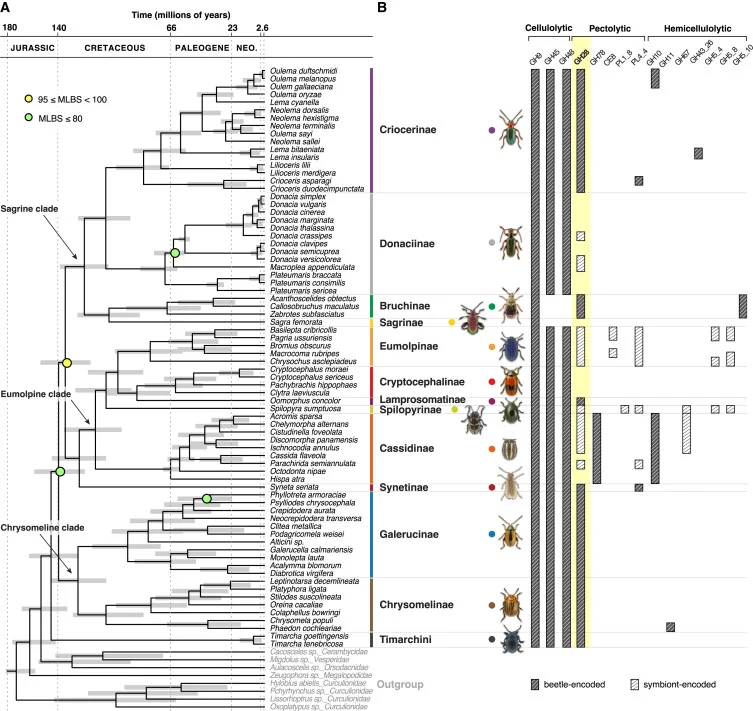

Figure 1 Dated phylogeny of the leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae) and plant cell wall-degrading enzymes encoded by hosts and symbionts

Figure 1 Dated phylogeny of the leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae) and plant cell wall-degrading enzymes encoded by hosts and symbionts

(A) A codon-based nucleotide sequence alignment of 535 Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) single-copy orthologous genes (containing 390,783 sites) found to be common to all transcriptome datasets was used to perform a maximum likelihood analysis with 1,000 ultrafast-bootstrap replicates. The best model of nucleotide evolution was the generalized time reversible (GTR) model, with empirical base frequencies count (+F) and FreeRate model (+R8). Support values (MLBS, maximum likelihood bootstraps) for nodes that were not maximally supported are indicated by either yellow (MLBS values greater than or equal to 95%) or light green circles (MLBS values lower than 80%). Bars on nodes correspond to the 95% credibility intervals of node-age estimates. Datasets used as an outgroup correspond to species of other families of Chrysomeloidea (Cerambycidae, Orsodacnidae, and Megalopodidae) as well as species of weevils (Curculionidae). The latter datasets were used to root the tree. Leaf beetle photos are courtesy of Lech Borowiec and Veit Grabe (used with permission). From top to bottom: Oulema melanopus, Lilioceris lilii, Crioceris asparagi, Donacia marginata, Macroplea appendiculata, Plateumaris sericea, Acanthoscelides obtectus, Sagra femorata, Chrysochus asclepiadeus, Clytra laeviuscula, Oomorphus concolor, Spilopyra sumptuosa, Chelymorpha alternans, Hispa atra, Syneta seriata, Phyllotreta armoraciae, Diabrotica virgifera, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, Phaedon cochleariae, and Timarcha tenebricosa.

(B) Genes encoding PCWDEs were manually curated, categorized as either glycoside hydrolases (GHs) or polysaccharide lyases (PLs), and further classified according to their putative substrate. Dark gray bars indicate beetle-encoded PCWDEs, while light gray bars denote bacterial symbiont-encoded PCWDEs.

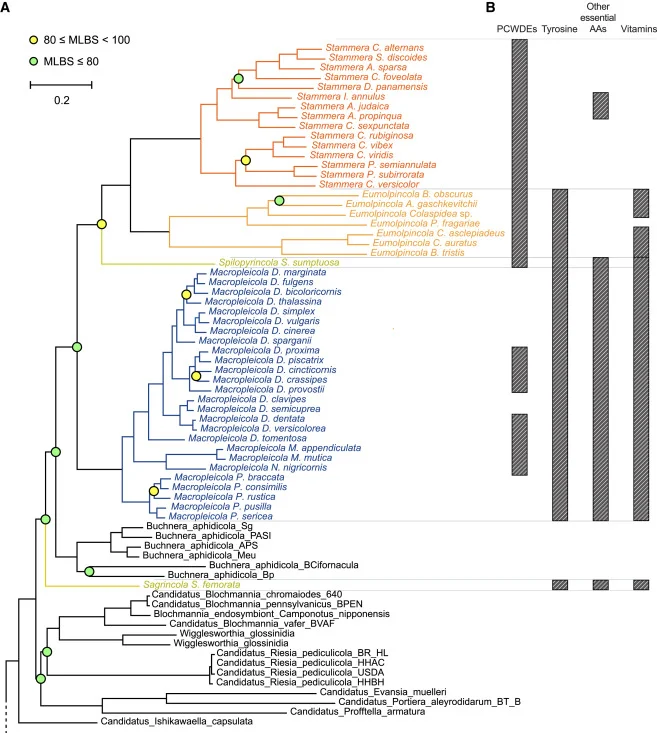

See also Figures S1, S4, and S7 and Tables S1 and S5. Figure 2 Phylogeny and genomic features of bacterial symbionts across the Chrysomelidae

Figure 2 Phylogeny and genomic features of bacterial symbionts across the Chrysomelidae

(A) Phylogenetic placement of Chrysomelidae symbionts in relation to free-living and other symbiotic bacteria. The maximum likelihood phylogeny was constructed using a concatenated protein alignment of 31 single-copy core genes. Support values (MLBS, maximum likelihood bootstraps) for nodes that were not maximally supported are indicated by either yellow (MLBS values greater than or equal to 95%) or light green circles (MLBS values lower than 80%). (B) The distribution of host-beneficial factors encoded by Chrysomelidae symbionts is indicated by gray bars. See also Figure S4. Figure 3 Symbiont localization in representatives of four Chrysomelidae subfamilies

Figure 3 Symbiont localization in representatives of four Chrysomelidae subfamilies

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed on adults (left) and larvae (right) of Cassida rubiginosa (Cassidinae), Chrysochus asclepiadeus (Eumolpinae), Donacia vulgaris (Donaciinae), and Sagra femorata (Sagrinae), using a combination of general eubacterial and symbiont-specific probes (see STAR Methods), resulting in green/yellow staining of bacterial symbionts. Counterstaining of host cell nuclei was achieved with DAPI. Cartoons of adults and larvae reflect the host’s morphology and the localization and structure of symbiotic organs (green), as well as the gut (brown) and adult reproductive tract (blue) for reference. FISH micrographs represent cross-sections through the adult and larval symbiotic organs and adult transmission organs. Note that Donaciinae adults lack a separation of symbiont populations into symbiotic and transmission organs, so both images show the symbionts’ localization in the Malpighian tubules. Scale bars represent 50 μm. See also https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(24)01696-8?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0960982224016968%3Fshowall%3Dtrue#mmc5.

Kirsch, Roy; Okamura, Yu; García-Lozano, Marleny; Weiss, Benjamin; Keller, Jean; Vogel, Heiko; Fukumori, Kayoko; Fukatsu, Takema; Konstantinov, Alexander S.; Montagna, Matteo; Moseyko, Alexey G.; Riley, Edward G.; Slipinski, Adam; Vencl, Fredric V.; Windsor, Donald M.; Salem, Hassan; Kaltenpoth, Martin; Pauchet, Yannick

Symbiosis and horizontal gene transfer promote herbivory in the megadiverse leaf beetles

Current Biology (2024) 10.1016/j.cub.2024.12.028

Copyright: © 2025 The authors.

Published by Elsevier Inc. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.