|

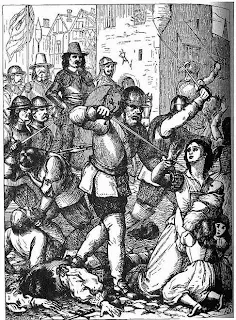

| Massacre at Porterdown Bridge. |

Part 3 of A History of Ireland

The Gaelic Rebellion.

The Gaelic rebellion had its greatest impact in Ulster because that is where most of the Protestants in Ireland were. It was in Ulster that the worst atrocities were enacted. The facts are difficult to disentangle from mythology but the Protestants firmly believe the accounts, and this is what now matters. One such incident is still depicted on the banners of the Orange Lodges today. It took place in November 1641. A party of 100 Protestants, who had been taken from their homes, stripped and robbed, were taken to the bridge at Porterdown and, so it is alleged, were there thrown and driven over the parapet into the river to drown. Those that could swim were shot or clubbed on the head as they came ashore and some Catholics even got into boats and bashed them with oars as they were drowning.Did this event really happen? Are the numbers and manner of their deaths accurate? Whatever the truth, Protestants believe it, as atrocities undoubtedly did occur on both sides during the 1641 rebellion. It confirmed in protestant minds the hostility of the Gaelic people to them and increased their isolationism and insecurity still further. The Royal Commission which followed the rebellion, records:

And for this deponent and many others were stayed behind, diverse tortures were used upon them ... and this deponent for her part was thrice hanged up to confess to money, and afterwards let down, and had the soles of her feet fried and burned at the fire and was often scourged and whipt...

And a great number of other Protestants, principally women and children, whom the rebels would take, they pricked and stabbed with their pitchforks, skeans and swords and would slash, mangle and cut them in their heads and breasts, faces, arms, and hands and other parts of their bodies, but not kill then outright but leave them wallowing in their blood to languish and to starve them to death.

The spectre of these events, real or imagined, still looms large in the Ulster Protestant psyche.

As the English parliament became more puritan and moved towards civil war with the King, so the Irish Catholics of both races became more and more to identify with a common cause. In 1641, at Clownes Castle, County Kildare, the former defensive bulwark of the Pale defending the seat of English government in Dublin, an event took place which had enormous symbolic significance. James Eustace, an English Catholic, drew his sword for Catholicism against the English government. It was here too that Protestant atrocities were recorded. Women and children were slaughtered and the garrison was hanged when it surrendered. Eustace’s ninety-year-old mother was killed when her jaw was smashed to get the keys to a secret room in the castle, which she was hiding in her mouth.

The people of Ireland were being driven by atrocity into two religious camps regardless of race. This process was to be given added impetus by a man who was to arrive in Ireland at the end of the decade. His name was Oliver Cromwell.

Cromwell

|

| Oliver Cromwell |

An English Catholic, Sir Arthur Aston, a veteran Royalist of the Civil War, commanded Drogheda. Cromwell’s superior artillery soon breached the walls but the first attempt to storm the breach led to considerable losses and the attempt failed. This so infuriated Cromwell that he showed no mercy when the garrison finally fell. He wrote:

Being in the heat of action, I forbade them to spare any that were in arms in the town

|

| Cromwell at Drogheda |

The Officers were knocked on the head and every tenth man of the soldiers killed and the rest shipped to the Barbadoes (sic) ... I think that we put to the sword altogether about 2,000 men ... [this was all done in the spirit of God] and therefore it is right that God alone should have all the glory.

Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland was devastating. All Irish Catholics, as suitors of the ‘Whore of Babylon’ (the Pope) were to be trodden under and the Irish Protestants were to triumph. From Drogheda, Cromwell’s Protestant New Model Army moved south to Wexford where it ran amok in the town killing at least 2,000, of whom 200 were women and children slaughtered in the marketplace.

With his triumph complete, he set about establishing Protestant rule with characteristic puritan zeal. All Catholic lands east of the Shannon were confiscated and given to his soldiers and those who had financed his campaign. Those dispossessed were driven west of the Shannon to the barren and remote provinces of Connaught. The final humiliation of the Catholic landowners was total. It was, however, only the landowners and their families who were transported across the Shannon. Their former tenants and labourers stayed behind to serve their new, hated, Protestant masters; masters who had been responsible for the massacres of Drogheda and Wexford.

|

| Land Ownership in Ireland Before and After Cromwell's Penal Laws |

With the restoration of the monarchy and the succession of the Catholic James II in England, Irish Catholics looked forward to better times, and their optimism seemed well-founded for a while. Catholics were appointed to high office in Ireland and a Catholic-dominated Irish parliament revoked the Cromwellian land settlement. However, it was not to be. England was about to change its Catholic King for a Protestant one and part of the drama was to be played out on Irish soil.

|

| Siege of Londonderry |

The city became divided between loyalty to the still legitimate King James and the fear of a Catholic garrison as a time when Catholics were believed to be massacring Protestants. The Protestant Bishop of Londonderry and other Protestant establishment figures found it unthinkable that they should try to keep royal troops out of a royal garrison, but the independently-minded Presbyterians had no such qualms. The official decision had been taken to admit the troops when suddenly thirteen apprentice boys of the city seized the keys to the gates of Londonderry and, on the 7 December 1688, slammed them shut in the face of the Redshanks. Presbyterian Protestants had again been let down by the establishment and had had to save themselves.

|

| Breaking the Boom |

There was starvation and sickness through the summer and dogs, cats, mice, candles and leather were eaten. Thousands died of starvation and disease. At one point during the siege, a shell containing the terms for surrender was fired into the city. The reply was simple, defiant, “No Surrender!” It has become the watchword of Ulster Protestantism.

On 28 July 1689, the British ships in the Foyle at last decided to break the boom, and, under fire from the Jacobites, they finally sailed into the quay with supplies and the siege of Londonderry was over. The raising of the siege led directly to the defeat of James II in Ireland. In 1690, William landed at Carrickfergus Castle and won great and decisive victories at the Boyne and at Aughrim. All Catholic armies in Ireland surrendered in 1691 and thousands of Catholic troops were sent into exile where they became the ‘Wild Geese’ who served in the army of Louis XIV of France. Orange had triumphed over Green and the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland was assured.

On 28 July 1689, the British ships in the Foyle at last decided to break the boom, and, under fire from the Jacobites, they finally sailed into the quay with supplies and the siege of Londonderry was over. The raising of the siege led directly to the defeat of James II in Ireland. In 1690, William landed at Carrickfergus Castle and won great and decisive victories at the Boyne and at Aughrim. All Catholic armies in Ireland surrendered in 1691 and thousands of Catholic troops were sent into exile where they became the ‘Wild Geese’ who served in the army of Louis XIV of France. Orange had triumphed over Green and the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland was assured.The Ulster Protestants had held out and triumphed over adversity, defiant to the end, and confident of God’s support and protection. The "No Surrender!" tactic had worked, as they knew it would. They also learned one other lesson from the presence of the British ships in the Foyle: though they may need Britain, they are essentially on their own, and it is that sense of self-reliance and defiance in adversity which is at the heart of Ulster Protestant psychology 300 years later. The siege Londonderry still goes on. The Ulster Protestant is continually on guard against the Papists who committed the atrocities of 1641 and who tried, and failed, to starve them into submission in 1688.