I had a brief encounter with a mouse the other day. Not one quite so dramatic as Burns' - it's a long while now since I followed a horse-drawn plough. In fact, to be strictly accurate, it's a long while now since I

saw a horse-drawn plough. They even had them-there tractor things when I was a child.

No. My encounter was a lot more mundane.

Every morning I feed my birdies - a flock of (mostly) wood-pigeons, collared doves, starlings, house sparrows and other assorted birds in season - at the bird table and various feeders we have in the back garden. I buy the mixed birdseed in 20 Kg. sacks along with bags of dried meal worms and peanuts and store it in our garden shed.

To a Mouse

(Written by Robert Burns in Gallowegian dialect supposedly after he had turned over the nest of a field mouse with his plough. This poem illustrates Burns' tolerance to all creatures and his innate humanity.)

Wee, sleekit, cowran, tim'rous beastie,

O, what a panic's in thy breastie!

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi' bickering brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an' chase thee,

Wi' murd'ring pattle!

I'm truly sorry Man's dominion

Has broken Nature's social union,

An' justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle,

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An' fellow-mortal!

I doubt na, whyles, but thou may thieve;

What then? poor beastie, thou maun live!

A daimen-icker in a thrave 'S a sma' request:

I'll get a blessin wi' the lave,

An' never miss't!

Thy wee-bit housie, too, in ruin!

It's silly wa's the win's are strewin!

An' naething, now, to big a new ane,

O' foggage green!

An' bleak December's winds ensuin,

Baith snell an' keen!

Thou saw the fields laid bare an' wast,

An' weary Winter comin fast,

An' cozie here, beneath the blast,

Thou thought to dwell,

Till crash! the cruel coulter past

Out thro' thy cell.

That wee-bit heap o' leaves an' stibble,

Has cost thee monie a weary nibble!

Now thou's turn'd out, for a' thy trouble,

But house or hald.

To thole the Winter's sleety dribble,

An' cranreuch cauld!

But Mousie, thou are no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o' Mice an' Men,

Gang aft agley,

An' lea'e us nought but grief an' pain,

For promis'd joy!

Still, thou art blest, compar'd wi' me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But Och! I backward cast my e'e,

On prospects drear!

An' forward, tho' I canna see,

I guess an' fear!

Robert Burns, 1785

I used to just stand the sacks of seed in the shed and fill a small container to take to the bird table until a family of mice set up home in the shed and learned to chew holes in the sacks, so I bought a plastic dustbin with a clip-on lid in which I also keep a plastic bucket to take seed, mealworms, peanuts and scoop to the garden in. Initially I felt a little bad about locking their food away and use to put a little seed and a few peanuts out for the mice but I decided it was best to wean them off their increasing welfare dependency and encourage them to earn an honest living.

A couple of days ago though, one little mouse had decided to use its entrepreneurial initiative and, when my back was turned and the lid was off, had had jumped or fallen into the deep plastic bin - with smooth sides.

My initial surprise was to discover that there were still mice in the shed. The mouse's initial surprise was to see the bottom of a large, black plastic bucket begin to descend, followed quickly by a large pair of eye and a human voice saying, "Hello! Okay! Let's see you get yourself out of there then!"

Isn't it interesting how quickly mice get over that initial panic and, after running round the perimeter of the bin three times, stop, look up, sit back on their haunches and wash their face.

So, what to do now then? In times gone by I would have thought nothing of picking it up by the tail and giving its head a quick flick against a wall then chucking it to the nearest cat or onto the compost heap. Maybe I'm getting soft or maybe I just appreciate living things a little better. Whatever, I decided to let nature take its course and do a little experiment. How would the mouse get itself out of an impossible situation?

Maybe it didn't appreciate the situation fully but my little mouse just picked up a sunflower seed and proceeded to take out the kernel and eat it. Maybe it needed some energy.

Of course, given a practically unlimited supply of food in comparison to its size, and not needing water beyond what they can get from their food, even dry seeds, the mouse wasn't actually in any real danger. It

could have lived its entire life in that bin so maybe its risk assessment was a little different to what mine would have been. Never-the-less, my little mouse did try to climb up the sides a few times, then it tried jumping - as though its ability to jump about four inches was going to be enough to get to the top, about 30 inches away. But it was obviously worth a try - yer gets owt for nowt!

So I thought, let's see how intelligent you are. How quickly can you learn to climb a piece of garden string?

So I pulled out a length of string from one of those balls of green garden twine which was standing on the rack next to the food bin, and let it hang loosely down to the surface of the seed.

- Mouse finds string and starts to climb. String is loose and stretches out so mouse makes no progress and gives up.

- Mouse tries again and pulls string to make it tight then starts to climb it. Falls off.

- Mouse tries again and climbs string until it can reach the rim of the smooth plastic bin with its front feet. Lets go with its hind feet but loses grip and slips back into the bin.

- Mouse climbs up above the rim of the bin so its hind feet can stand on it. Walks round the rim of the bin a short distance then hops onto the rack, washes its face, and disappears.

In four steps the mouse had learned progressively by trial and error, and had got itself out of the bin.

What we had there was an interesting interaction in terms of genes and memes.

The mouse found itself in a predicament brought about because it exists in an environment in which I exist and in which the meme for enjoying nature and wanting to attract birds into my garden exists. The mouse genes had produced an animal which needs to feed and which actively looks for food, using a whole range of senses and abilities, not least of which is curiosity and an ability to discover by trial and error.

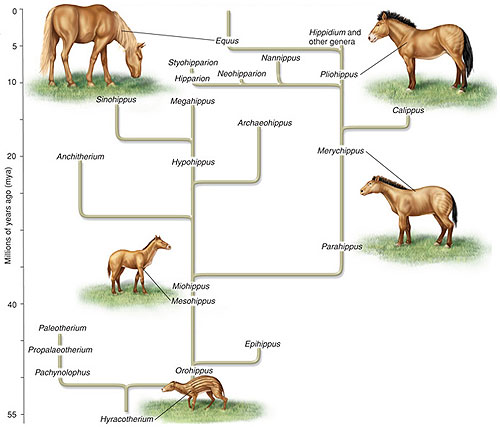

It survived because I have a mixture of memes and genes which make me interested in wildlife and an appreciation that they, like us, are the end-products of an incredible evolutionary process in which every one of our ancestors survived, that to end that gene-line would bring to a halt a process which started three and a half billion years ago and which has never yet failed, and an understanding that the simple fact of sharing our history and having ancestors in common with all living things gives us a connectedness and a kinship with it which is truly inspiring and deeply spiritual.

And the mouse had genes which allowed it to make an intelligent assessment of its situation, plan an escape strategy and improve its technique by trial and error whilst learning from its mistakes and keeping its objective in sight. With a little help from its friend.

And I spent a magical twenty minutes or so enjoying an interaction with a wee, sleekit, cowran, tim'rous beastie.

BBC News - Twitter 'report abuse' button calls after rape threats

BBC News - Twitter 'report abuse' button calls after rape threats